The internment of Japanese Americans during World War II remains a stain on American history. From 1942-1946, close to 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry were relocated to internment camps in the western United States. Over sixty percent of the interned people were American citizens. The motivation for this program was born out of wartime fear following the attack on Pearl Harbor and an underlying current of racist discomfort that was already present. More than 40 years after the final camp closed in 1946, and 30 years ago today, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, a law that awarded restitution to over 80,000 people.

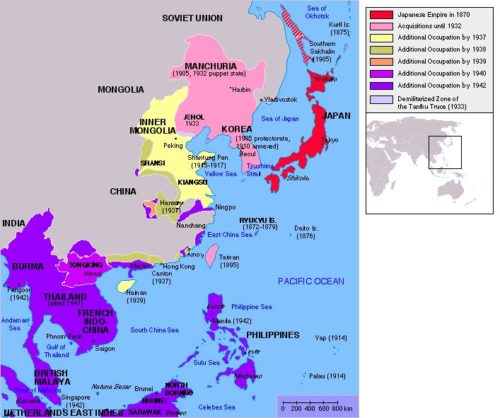

Internment began in February, 1942, following President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066. Initially, Roosevelt and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover put little stock in rumors of anti-American activity and potential sabotage. However, the U.S. had just seen the unexpected Pearl Harbor attack after years of Japanese conquest in the Pacific between 1936 and 1942. Japanese occupied or controlled areas included all of Korea, portions of mainland China, Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines, and many more.

A fear that an invasion of the West Coast of the U.S. was imminent festered and grew, exacerbated by the Roberts Commission report on the Pearl Harbor attack and statements by Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, head of the Western Defense Command, spreading a myth that Japanese immigrants remained loyal to the Emperor no matter where they lived. Testifying before Congress in 1943, DeWitt went so far as to say, “I don’t want any of them [persons of Japanese ancestry] here. They are a dangerous element. There is no way to determine their loyalty… It makes no difference whether he is an American citizen, he is still a Japanese. American citizenship does not necessarily determine loyalty… But we must worry about the Japanese all the time until he is wiped off the map”

The order resulted in thousands being moved to camps and detention facilities in nearly 70 locations spread throughout the U.S. A number of the long-term camps were labeled as relocation centers, while detention camps also held a sizeable number of German and Italian-Americans. Over 30,000 of the detainees were children, among them George Takei, who would later gain fame as Lieutenant Hikaru Sulu on Star Trek. Takei, who was first interned at five and spent time in multiple facilities, would later star in the Broadway musical Allegiance, based on his own experiences in the camps.

Japanese Relocation, produced by the Office of War Information, attempted to justify the government’s case for internment.

After the war, the internment locations went through a closing process that lasted, in some cases, until 1946. The internment experience had cost the victims property, careers, and, in a few cases, their lives. Widespread depression and trauma among detainees was observed in reports from the War Relocation Authority. An early attempt to compensate the population came with the American Japanese Claims Act of 1948, which allowed Japanese-Americans to try to recoup property losses. Unfortunately, detainee records destroyed by the IRS and documentation lost due to the movement of families between their homes and various facilitiesed to a number of unsuccessful filings; over 26,000 claims were filed, but of the possible total award of $148 million in requests, only $37 million was ever paid out.

Reagan opened the signing ceremony by saying, “We gather here today to right a grave wrong.”

The Act covered a number of items, including a formal apology to those interned on behalf of the government, and a tacit acknowledgement that the relocations were an injustice. The act granted every living detainee the sum of $20,000; beginning in 1990, checks were sent to 82,219 survivors. Items 6 and 7 of the Purposes section of the Act remain strikingly relevant today, as they “discourage the occurrence of similar injustices and violations of civil liberties in the future” and “make more credible and sincere any declaration of concern by the United States over violations of human rights committed by other nations.” Furthermore, that Act codified that the entire policy of internment was based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership,” rather than any genuine threat.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I recently read your article describing the humane treatment of German POW’s in the Midwest, and this sterile article concerning the mistreatment/imprisonment of Japanese Americans during WWII. When can we expect to see an article exploring the disparate maltreatment of uniformed, Black/ African-American US soldiers and German POW’s in our southern states of the USA??

An article which explores the relationship between the Supreme Court Decision which upheld the inclusion of White Covenant Clauses in property deeds and its impact on the rights of Black/African Americans to purchase homes under the VA and FHA programs is well past due.

I truly look forward to your reply or to your coverage.