We are pleased to bring you this regular column by Dr. David Creel, a licensed psychologist, certified clinical exercise physiologist and registered dietitian. He is also credentialed as a certified diabetes educator and the author of A Size That Fits: Lose Weight and Keep it off, One Thought at a Time (NorLightsPress, 2017).

Do you have a weight loss question for Dr. Creel? Email him at [email protected]. He may answer your question in a future column.

Batter Up

Weight management is unlike many disciplines in the medical field. When a surgeon operates to remove a gallbladder, the operation is almost always successful. When you take an antibiotic for an infection, you usually get better. When you wear a cast, the bone generally heals. Weight management is more like baseball than medicine. If you’re a good major league hitting coach, your players may get a base hit three out of ten times. Your hitter may only hit a home run once every 20-30 at bats. Like hitting a 90-mile per hour fastball, weight management is hard. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a program of studies that includes ongoing assessment of weight. One study from data including over 14,000 people sheds light on how difficult weight management can be.

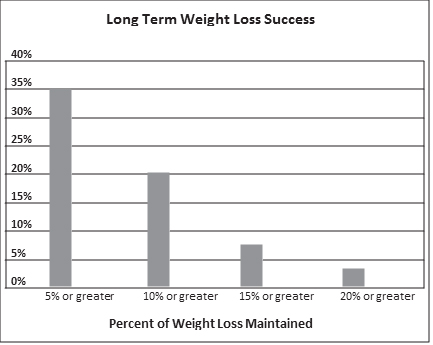

The figure below shows the percentages of people able to lose weight and keep it off for at least one year. As you can see, losing and keeping off 5 percent of weight (a 12-pound weight loss if you weigh 240 pounds) happens for just over one-third of people. This is sort of like hitting singles. The probability of losing and keeping off 20 percent of your body weight (48 pounds if you weigh 240 pounds) is similar to the average professional baseball player’s chances of hitting a homerun at any given at bat — 4.4 percent, or 1 out of 23.

One big problem with weight management is that most of us want to hit a home run; we forget that singles matter. Additional research tells us that a 5 to 10 percent weight loss improves health, helps prevent diseases like type 2 diabetes, and improves other health conditions such as high blood pressure.

It’s important to point out that the NHANES data don’t differentiate between people who had bariatric surgery and those who lost weight without it. However, during the time of the study only about one out of every 2500 people had bariatric surgery, suggesting almost all these data relate to people who chose not to have surgery.

Weight loss after bariatric surgery is much greater than this, but those patients also risk short and long-term complications. In addition, most bariatric surgery procedures aren’t appropriate for people who have less than 75 pounds of excess weight (gastric banding procedures are exceptions and can be performed for people with various medical conditions who are 30 to 40 pounds or more overweight).

The following section on relapse prevention isn’t about hitting home runs or being happy with singles. Instead, I want to explore your approach to hitting with questions such as these:

- Can you keep your head in the game even after consecutive strikeouts or making an error in the field? That is, how do you handle holiday mishaps without falling back into old habits for an extended period of time?

- What is your approach to vacations, eating chocolate, or getting back on track after a binge?

- Do you continue to exercise even when you’re struggling with your eating?

You may hit homeruns with the amount of weight you lose — or you may hit singles. The important part is staying in the game without giving up, and continuing to focus on your health while balancing other parts of your life.

As previously discussed, bariatric surgery is a bigger bat, so to speak, and only certain folks should use it. Surgery is not better in all cases, and many of you will be using a smaller bat. However, all great baseball players have common characteristics to their swing, no matter what size bat they use. Along those same lines, we need certain attributes for successful weight management.

Check Your Weight, AND Keep Your Eye on Behavior

Research shows that frequent weighing helps prevent relapse. People who keep weight off tend to step on the scale at least weekly. By comparison, those who are unsuccessful with their weight often view the scale as a tripwire that punishes them if they take a step in the wrong direction. They weigh when they know they’re following a safe path, but avoid the scale when they veer a little off course.

In previous posts we covered ways to adjust our thinking in order to view the scale as a dependable friend giving us positive feedback to help correct our course. I encourage each client to use these skills and eventually reach a point of weighing regularly, especially when the body reaches a natural plateau after weight loss.

Even though regular weighing is extremely helpful to prevent relapse, weight doesn’t tell the whole story about progress. For example, a 40-pound weight loss can represent different things for different people, based on starting weight and weight-loss treatment. If a 400-pound man has gastric bypass surgery, loses 40 pounds, and then has a six-month weight plateau, he has probably relapsed. His lack of expected weight loss tells us there are problems. He probably returned to unhealthy eating patterns that might include high-fat snacks, sweet tea, or fast food.

Let’s compare this surgery patient to a woman who is less overweight, lost 40 pounds, and kept it off for three years without bariatric surgery. In her case, the weight plateau is probably a sign that she’s following a healthy eating plan and regular physical activity — even if she’s still 30 pounds overweight by medical definition. Her metabolism and appetite have adjusted to her new weight, so the plateau isn’t necessarily a sign of unhealthy habits.

As the previous figure suggests, most people who lose weight are still considered overweight or obese by body mass index (BMI), a simple weight to height calculation. It’s crucial for you to remember that maintaining weight loss has many health benefits even if the charts still indicate you’re overweight. Just because your weight plateaus at a number higher than you desire (or a BMI chart recommends) doesn’t mean you’re doing something wrong or you relapsed into old behavior. The only way to truly evaluate how you’re doing is to look at what you’re doing.

We can rarely define weight-related relapse with one behavior, so you need to look at many daily decisions when examining your lifestyle.

Comparing eating behavior relapse to drug abuse gives us another way to look at this concept. With drug use, an addicted person relapses when he returns to using drugs. It’s usually black or white — he’s either clean or relapsed. Although the addict often starts behaving in ways that predict relapse, we define relapse with specific behavior: He’s using again.

Weight management is different because the behaviors aren’t black and white. Eating cheesecake can be part of an overall healthy eating plan — or it may be one of many signals that someone has relapsed into old patterns. For successful long-term weight loss, you need to maintain a variety of healthy practices such as regular exercise, portion control, balance between food groups, and limiting calorie-dense foods.

Frequent weighing is a simple and helpful way to create a centerpiece for your relapse prevention plan. But remember, we weigh ourselves to become more aware of our behavior. And behavior should be the focus of our plan to get back on track when we struggle.

Identify and Plan for High-Risk Situations

If you have an important work-related meeting at eight o’clock in the morning and a snowstorm is supposed to hit your area at 4:00 a.m., what would you do? If you’re planning a long car trip, how do you prepare? What if your child complains of a stomachache before bed? Experienced snowy weather residents, veteran travelers, and wise parents understand each of these situations is high-risk for something undesirable to happen. Being on time for a meeting may require getting up early to shovel the driveway and allow for a longer commute. An experienced traveler packs in advance and has the car serviced before a long trip. When a child complains of stomach problems before bedtime, parents soon learn to prepare for a possible upchuck in the middle of the night. (My mother sent us to bed with “puke sacks,” and my wife’s family used bowls, which makes me leery of eating soup when visiting them.)

My point is, most of us know how to identify, plan, and prepare for high-risk situations in our lives. We know what works and what doesn’t. Based on experience, we change our approach over time.

When it comes to exercising and eating the right foods, high risk situations are all around us. What events jeopardize your weight management goals? Weekends, vacations, holidays, celebrations, stress, and any life transition can lead to lapses and even full-blown relapses. Think about the last time you lost weight and then began regaining it. What was going on? If similar things happened again, how could you prepare beforehand and how could you handle things differently?

Some high-risk situations are small, day-to-day events that throw us off course. Matt told me he had an issue with overeating cashews at work. He always kept a can of nuts in his desk drawer in case he worked late or missed lunch. But during normal work hours when he did have lunch, the cashews presented a problem. When things got hectic or he felt a bit hungry he’d help himself to “just one handful.” That small snack turned into mindlessly picking at cashews all afternoon until the entire can was empty. He could keep other foods at his desk without a problem, just not cashews. He said cashews weren’t a problem at home. But the combination of his work environment, plus cashews, created a perfect storm for Matt.

Other people may be overcome by shopping when hungry, having homemade cookies at home during a stressful time, driving with snack food in the passenger seat, and a dozen other scenarios that can be avoided by planning ahead.

Other high-risk situations are unavoidable. Only a hermit could totally avoid social events that challenge healthy eating. Still, we need to anticipate problems whenever possible and have a plan to stay on track. Every stressful event you prepare for is helping you develop skills to handle future situations, even the toughest ones. The longer you practice those coping behaviors and the more natural they feel, the less likely you are to fall apart when your life changes.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now