This column by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

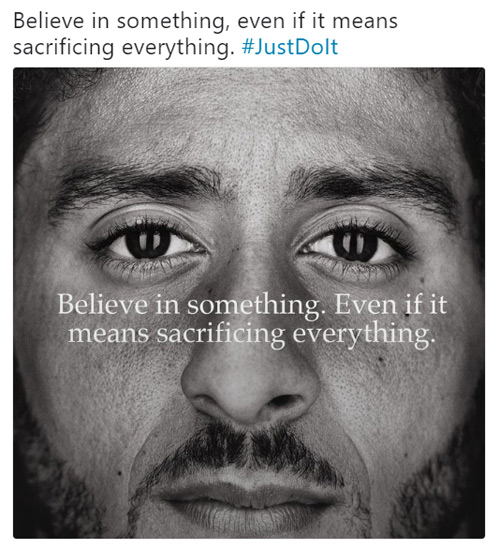

The recent reveal of Nike’s 30th anniversary “Just Do It” ad campaign featuring Colin Kaepernick (one piece of a multi-part endorsement deal the apparel giant signed with Kaepernick) has reignited the firestorm of debate around the former San Francisco 49ers quarterback. Critics of Kaepernick and his protests have responded by trashing and burning Nike gear and threatening to boycott the brand entirely. Fans and defenders of Kaepernick have praised the ads as a long-overdue recognition for all that he has sacrificed in support of his beliefs and activism.

Ever since he began his protests during the 2016 NFL preseason (first sitting during the national anthem and then, after conferring with former Green Beret and NFL player Nate Boyer, kneeling), Kaepernick’s athletic activism has been frequently compared to a couple of famous and controversial 1960s moments: boxing champion Muhammad Ali’s 1967 Vietnam War draft resistance; and Olympic sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ 1968 medal ceremony protest. Yet Kaepernick could also be linked to the anti-racist and anthem protests of another famous African American athlete, one widely perceived as less controversial and more universally beloved but in reality just as radical in his activism: Jackie Robinson.

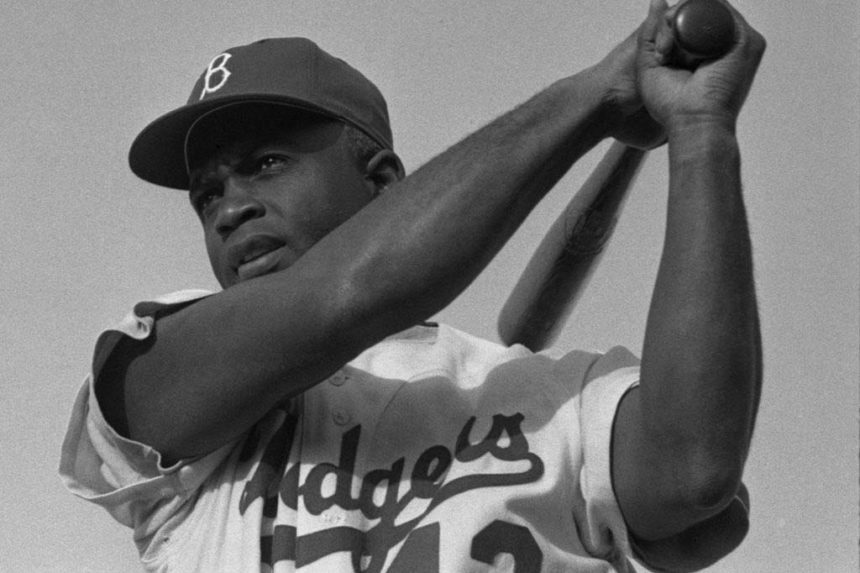

Robinson’s public anti-racist activism began in 1944, three years before he broke into the Major Leagues with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Already a well-known athlete from his hugely successful time at UCLA (where he was the first person to letter in four different sports), Robinson had volunteered for the army and was serving as a lieutenant at Fort Hood in Texas. As Robinson narrates the incident in his autobiography I Never Had It Made (1972), he was riding an army bus and chatting with the light-skinned wife of a fellow African American officer when the bus driver, “saw what he thought was a white woman talking with a black second lieutenant. [The driver] became visibly upset, stopped the bus, and came back to order me to move to the rear.” Not one to give in to such demands, Robinson refused and was eventually removed from the bus by military police and court-martialed for “disrespecting a senior officer and failing to obey a direct command.”

Although Robinson had the support of his immediate commanding officer, Colonel Paul Bates, the army pursued the court martial and brought Robinson to trial. There Robinson continued to experience the inequities of the justice system for African American defendants, including a Southern-born defense lawyer who at least “had the decency to admit to [Robinson] that he didn’t think he could be objective” and removed himself from the case. Thanks to such “lucky breaks” (as Robinson himself called them), the support of Bates, and especially his own strong testimony, Robinson was acquitted on all charges and granted an honorable discharge from the army. But the incident made clear to Robinson that “there is one irrefutable fact of my life which has determined much of what happened to me: I was a black man in a white world. I never had it made.”

Robinson expressed that same perspective on race and America in relation to a strikingly familiar topic: athletes and the national anthem. Remembering the opening moments of his first World Series game, at the end of his 1947 rookie season, Robinson wrote,

There I was, the black grandson of a slave, the son of a black sharecropper, part of a historic occasion, a symbolic hero to my people. The air was sparkling. The sunlight was warm. The band struck up the national anthem. The flag billowed in the wind. It should have been a glorious moment for me as the stirring words of the national anthem poured from the stands. Perhaps, it was, but then again, perhaps, the anthem could be called the theme song for a drama called The Noble Experiment. Today, as I look back on that opening game of my first World Series, I must tell you that it was Mr. Rickey’s drama and that I was only a principal actor. As I write this twenty years later, I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world. In 1972, in 1947, at my birth in 1919, I know that I never had it made.

Robinson’s sentiments echo closely a number of Kaepernick’s points: the difference between athletic achievement and social justice; the continued presence and limiting effect of race even for those African Americans who achieve celebrity; and, most importantly, the opportunity to use occasions such as the pre-game anthem to raise collective awareness of those enduring issues and problems.

Colin Kaepernick is not Jackie Robinson, no more than he’s Muhammad Ali or Tommie Smith and John Carlos. Yet Kaerpernick and his peers’ protests are best understood when viewed through a longer lens: that of the unfolding history of African American athlete activism.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now