Science teaches us that whatever goes up, must come down. Myths teach us that Titans fall. And history is full of warnings, indicators that can predict future success or failure based on the patterns of previous behavior. Sometimes, all of those lessons can be applied to a situation, particularly one that’s dire enough to be studied, and learned from, and potentially avoided in the future. That’s the case with Lehman Brothers. Before 2008, they were the fourth-largest investment bank in the United States, and had been in business for more than 150 years. By September of 2008, they would declare bankruptcy with the largest filing in U.S. history, shaking the world economy and unveiling a tangled web of toxic assets, bad decisions, and litigation. What happened?

To understand how deeply woven Lehman had become in the financial fabric of America, you have to look at its origins. Lehman got its start as, of all things, a dry-goods store in 1844. Founded by Bavarian immigrant Henry Lehman as H. Lehman in Montgomery, Alabama, the store became H. Lehman and Bro. when Emanuel Lehman arrived in America. Another brother, Mayer, arrived in 1850, and the business was renamed Lehman Brothers. The brothers got involved in commodities trading when they began accepting raw cotton as payment at the store. They started a second business focusing only on trading, and it quickly outpaced the store as their prime source of income. Henry died of yellow fever in 1855, but the remaining brothers kept the commodities business going. Following the cotton trade as it shifted the center of its orbit to New York City, the brothers opened an office there in 1858.

As that business grew, it took on other markets, like coffee, and expanded into railroad bonds. The company participated in financing the reconstruction of Alabama after the Civil War. By 1889, it had underwritten its first public offering. In 1906, Phillip Lehman, Emanuel’s son, led the firm to partner with Goldman, Sachs & Co. to bring General Cigar Co. to market. Through the ’20s and ’30s, the firm underwrote dozens of further issues, including those for F.W. Woolworth Company, R.H. Macy & Company, B.F. Goodrich Co., and The Studebaker Corporation. They survived the Great Depression in part by shifting their attention to venture capital. They underwrote the initial public offering of DuMont Laboratories ( the first maker of televisions), RCA, and companies in the oil industry, including Haliburton. In a sense, Lehman became big simply by being big and thinking big; they enabled the launch of titans of industry and brands that became household names.

By the financially turbulent 1970s, Lehman embarked on a series of mergers and acquisitions to stay alive. They acquired Abraham & Co. in 1975 before merging with Kuhn, Loeb, & Co. in 1977. As a result, the newly rechristened Lehman Brothers, Kuhn, Loeb Inc. became the fourth-largest investment bank in the United States. Shearson/American Express bought the company for $360 million in 1984, and they in turn merged with E.F. Hutton & Co. in 1988. All of this consolidation guaranteed that (the again renamed) Shearson Lehman Hutton would remain a powerful institution in the marketplace, but it was also emblematic of the enormous financial power being concentrated into the hands of fewer and fewer firms. By 1994, American Express spun out Lehman Brothers Holding, Inc. in an IPO. The chairman and CEO would be Richard Fuld, Jr. He would turn out to be their final chairman and CEO.

The pending 2008 financial disaster was presaged by an even larger American tragedy. During the attack on the World Trade Towers on September 11, 2001, one Lehman employee was killed and the three Lehman floors in the Towers were destroyed. When the Towers collapsed, the debris rained serious damage upon neighboring Three World Financial Center, which housed the majority of Lehman’s global operations. Over 6,500 employees had to be relocated. The following month, Lehman bought a 32-story building from Morgan Stanley for $700 million; that, along with expanded grounds in Jersey City, would be the home for the company. Lehman found itself starting the millennium with serious losses.

Just prior to the attacks, in 2000, Lehman began making moves in mortgage origination. They bought BNC Mortgage LLC, a subprime lender, to join an earlier acquisition, Aurora Loan Services. Subprime lending, in theory, allowed people with less substantial credit to secure loans so that they could buy a home. By 2003, Lehman ranked third in loans and had made more than $18 billion from them; the next year, they passed $40 billion. BNC and Aurora were lending an astonishing $50 billion a month by 2006. At the outset of 2008, Lehman’s assets were valued at $680 billion; however, they only had $22.5 billion in firm capital. These were dangerous waters in which to tread, as market fluctuations could put their entire structure in jeopardy. Even a small loss in real estate value at that point would have a massively detrimental effect to the business.

Things had begun to take a negative turn in 2007 when, as TheStreet.com put it in the August 22, 2007 piece by Laurie Kulikowski, Lehman “amputate[d] their mortgage arm.” That’s because Lehman closed BNC, a move that cut 1,200 jobs. Lehman wasn’t alone. Other lenders were closing as the subprime mortgage crisis began in earnest. Housing prices began to fall after a 2006 peak, but homeowners found themselves unable to refinance loans; lenders wouldn’t work with people on loans for homes that were suddenly worth half or less of the original value.. Institutions had been lending larger and larger amounts of money to borrowers with weak credit histories; in turn, those borrowers struggled to make payments. Lenders began absorbing losses due to defaults and delinquencies. At the news of BNC’s closure, Lehman’s stock only fell 34 cents. It was about to get much worse.

Matthew Notowidigdo, an associate professor of economics at Northwestern University, worked for Lehman prior to 2008. He says, “I met some of the smartest people I’ve ever worked with. Even when I decided to leave my job to go to graduate school, I thought that there was at least some chance I would want to return after I had finished my degree. I really didn’t see a Lehman bankruptcy in the cards.”

Notowidigdo wasn’t alone in that view. While it was obvious to observers that Lehman had experienced some difficulties, it seemed absurd prior to late 2007 that they would be in that much trouble. In fact, Notowidigdo indicates that one of the common refrains about Lehman’s troubles might not be entirely accurate. He says, “I think the idea that subprime lending and predatory lending played an important role in financial crisis is something that economists are still debating in the pages of their academic journals . . . Surely subprime played a role, but I am increasingly seeing papers arguing that it may not be the predominant explanation for the housing boom and bust. That is, it might make more sense to think of the 2008 crisis as originating from a widespread housing bubble, rather than a “subprime-fueled” housing bubble.” Again, that bubble comes from when housing values soar to unexpected, even potentially unreasonable, levels in the market, and then decline from unsustainable highs.

Robert Johnson, Professor of Finance for the Heider College of Business at Creighton University, also weighed in on the causes. He says, “Lehman, and many other financial institutions, became heavily involved in mortgage securitization – that is, the packaging of mortgages into various types of securities (called mortgage backed securities) and selling them to primarily institutional investors. In the run-up to the financial crisis, originating mortgages, packaging them into mortgage backed securities, and selling those securities was an extremely profitable business.” However, that kind of thing can go too far. In 2007, Lehman underwrote more mortgage backed securities than any other firm and had an $85 billion portfolio of mortgage backed securities.

Still, in 2007, Lehman was painting a rosy picture. As global investment bank Bear Stearns began to circle the drain, based in part on the failure of two of their subprime mortgage funds, market observers started to speculate that Lehman might be in the same boat. However, Lehman’s first quarter conference call indicated a profit of $489 million; while other financial services firms posted losses, Lehman’s stock rose 46 percent on the back of the call.

Here’s where Lehman’s fall began in earnest. By mid-2008, Lehman faced massive losses from the housing bubble and subprime mortgage crisis. The loss came primarily from Lehman’s refusal or inability to dump lower-rated bonds, meaning that they held on to things too long until they lost their value. Johnson says, “What happened was that home delinquencies in the subprime market rose dramatically and spread to the rest of the U.S. housing market. The mortgage backed securities Lehman held in its portfolio fell dramatically in value and the firm became insolvent and was forced to declare bankruptcy when no willing suitors could be identified.” As reported in The New York Times on August 22, 2008, Lehman’s loss by the second fiscal quarter was $2.8 billion; this necessitated a sale of $6 billion in assets and a reduction of over 1,500 jobs.

Erin Callan had been Lehman’s CFO for six months, and she was the one on the upbeat first quarter call and the bleak second quarter follow-up. Shortly after that, she stepped down. In September of 2008, she told CNN Money, “Nobody thought [bankruptcy] was a possibility. In other downturns, market conditions improved. The firm had a history of coming out on the other side and doing well. But the harsh reality of this environment is that asset prices were declining at a shockingly fast pace, so the firm ran out of time. Raising money to address declining prices wasn’t going to work.”

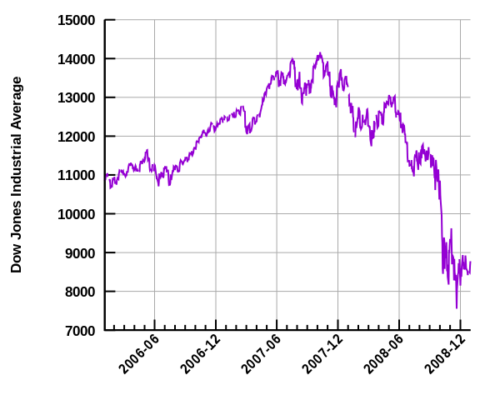

Korea Development Bank explored buying the bank, and those reports caused Lehman stock to close up 5 percent on August 22, 2008. However, when it became clear that KDB couldn’t find other partners, the deal did not materialize. When word got out that the takeover had stalled, Lehman stock dropped 45 percent on September 9. The ripple effect caused the S&P 500 to go down 3.4 percent and the Dow to drop 300 points. On September 10, Lehman announced a loss of $3.9 billion; stock dropped 7 percent as they said they would sell off their investment management piece. One day later, the stock dropped another 40 percent.

Other forces started to come into play. Bank of America and Barclay’s emerged as potential buyers, but both passed. By September 15, what had once seemed impossible became the inevitable. Lehman Brothers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

Notowidigdo acknowledges that the bankruptcy and what led to it can be hard for the average citizen to grasp. He says, “Many of [Lehman’s] investments were in the mortgage market, which left the firm vulnerable to sudden drops in housing values. Just as a homeowner can become ‘underwater’ when they start with limited amount of home equity and then their housing value drops significantly, Lehman rapidly went ‘underwater’ and had to file for bankruptcy. The firm just wasn’t sufficiently protected against a ‘housing bust’ scenario.” Ultimately, the major reason that the U.S. government didn’t step in to save Lehman Brothers is that it had just too much debt to save; in other bailouts, the government has gotten some type of payment back. They didn’t foresee that being the case with Lehman Brothers.

The numbers speak for themselves. The Lehman bankruptcy filing indicated that the company had bank debt of $613 billon, bond debt of $155 billion, and $639 billion in assets. Other Wall Street entities and the Federal Reserve got involved, with the other firms engineering assistance for Lehman’s liquidation, and the Fed taking “lower-quality assets” for government loans and assistance. Lehman’s shares dropped an additional 90 percent on the day of the filing. The Dow Jones would close down more than 500 points, its worst single-day drop since the 9/11 attacks. On September 17, the New York Stock Exchange issued a press release that they had “determined that the Company is no longer suitable for listing.”

The fallout lasted for years. In the wake of the filing, the various pieces of Lehman Brothers got carved up by buyers. Barclay’s picked up most of the North American operations, for example, and Nomura Holdings of Japan purchased the Asian and European divisions. The collapse shook the world economy and eventually led to the U.S. government intervening in the form of The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, which created the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP); the $700 billion bailout bought toxic assets in an effort to prop up a financial system that had been riddled with losses.

All of the action around Lehman Brothers reintroduced the phrase “too big to fail.” The phrase first gained popularity in 1984 when it was invoked by Congressman Stewart McKinney during the failure of Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Company, a financial implosion that led to the Federal Deposit and Insurance Corporation seizing the bank. Notowidigdo says, “It’s hard to imagine a situation where we suddenly decide that Facebook is ‘too big to fail,” for example. This is related to a view that many economists have that ‘banks are special’ — that is, the banking system is so highly regulated precisely because economists believe that bank failures are thought to impose particularly large costs on the economy. And the bigger the bank failure, the bigger the economic costs and collateral damage, which then logically becomes “too big to [let] fail.” Indeed, the government did hesitate to intervene on behalf of Lehman Brothers; after witnessing the economic impact, the Treasury did step in with an $85 billion loan to AIG, which was also about to fail.

Dylan Ratigan explains the Repo 105 practice on The Dylan Ratigan Show from March 12, 2010.

In the aftermath, a number of other issues came to light. The court-appointed examiner Anton R. Valukas revealed his findings of a year-long investigation in 2010. Among his observations was the fact that Lehman indulged in a practice called Repo 105, a bit of accounting prestidigitation that allowed the firm to switch out assets for cash. Lehman did this prior to publishing their financial statements, giving the appearance that the company had made a sale rather than a planned repurchase of their debt obligations. In Lehman’s case, they did this swap in a way that portrayed a better cash position, one $50 billion greater than the actual situation. Former MSNBC host Dylan Ratigan discussed this maneuver on his Dylan Ratigan Show in March of 2010; he called the procedure a fraud and compared it to trading a pile of cash for an empty garbage can so that everyone else would see you with cash, not realizing that all you had was an empty garbage can.

That same year, journalist Matt Taibbi wrote a piece for Rolling Stone called “Wall Street’s Naked Swindle.” Taibbi pointed out that a technically legal short-selling practice had been employed on a large scale against both Bear Sterns and Lehman Brothers. This atmosphere of betting against the market was described in great detail in Michael Lewis’s 2010 book, The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine, which covered those that saw the bubble and collapse coming and made moves that allowed them to profit from the events of the financial crisis. While it might be argued that the protagonists of the book and subsequent film version were played in a positive light, these practices certainly threw wood on the fire of the impending collapse.

Today, some observers are sounding alarms that we might be in for another recession. On a June 29 installment of All Things Considered on NPR with Chris Arnold, the discussion hinged on possible warning signs, including the possibility of a trade war built on tariffs and other practices. On the program, David Kotok, the chief economist with money management firm Cumberland Advisors, criticized the White House’s trade policy. He said, “You don’t invite compromise when you scream at the other guy . . . What’s the policy of the United States? Is it [Peter] Navarro? Is it Mnuchin? Is it Wilbur Ross? Is it Larry Kudlow? Is it the president, who changes his mind back and forth every day? How do you proceed?” That uncertainty has some analysts spooked, as does the yield curve that measures debt in the market; if long-term rates dip as low as short-terms bond rates on the curve, or what is called a flattening curve, that frequently demonstrates that conditions are favorable for stock losses, if not a recession.

Johnson points to other problems that could lead to a similar disaster. He says, “Mark Twain is reputed to have said that “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes” and to that extent we may have a similar crisis brewing in the student loan arena. Student loan debt is now the second highest consumer debt category – behind only mortgage debt. Over 44 million borrowers hold $1.52 trillion in student debt. Over a half a million borrowers owe more $200,000 in student loan debt. Rising student debt and increasing default rates can have a devastating on individual lives and the underlying economy.” He also notes that further actions by the Trump administration, including rolling back or weakening oversight rules that came in after the Great Recession.

Notowidigdo alludes to the fact that there’s still some debate about what caused the 2008 crash, and what might cause one now. For his part, he was doubly fortunate when it came to his Lehman exit. In addition to leaving the company before its collapse, he sold some of his Lehman stock to buy an engagement ring – but not all of it. “I really thought Lehman was going to be very profitable company for a very long time.”

Despite Notowidigdo’s optimism, Lehman Brothers didn’t survive. Lehman Brothers may have only been a piece of the Great Recession, but their fall can still serve as a stark reminder for everyone else of what not to do.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This is a well written and researched feature. It’s hard to believe such a calamity could have/would have occurred if the kinds of rules and regulations we had at mid-century had never been de-regulated in the first place!! THEY had been put in place after the country (and world) HAD been brought down in 1929 after years of fiscal irresponsibility in the ’20s. This had direct ties to Hilter’s insane rise to power, and the tragedy of yet a second World War. Really horrifying. In recent decades, a legal game of never-ending mergers, acquisitions and soooo much more out of control greedy filth; it’s only a matter of time before another kind of horror happens again, most likely in the forthcoming ’20s! The student loan bubble alone may do it. College “required” across the board now (to keep themselves in business) with a HUGE percentage of these grads doing Uber and/or having minimum wage jobs because college grads are a dime a dozen, among other economic realities. Yeah, no s— the default rate is so high! There’s a one-hour documentary online (“The College Conspiracy”) that gets down to business within the first minute. It’s from 2011, so the costs quoted are dated; but otherwise no. There are other videos from A LOT of unhappy college grads that justifiably feel they’ve been financially raped. This will eventually be enough to cause a crash and burn, never mind your Lehman Brothers and Goldman Sachs.