Editor George Horace Lorimer accepted Sinclair Lewis’s short story “Nature, Inc.” from The Saturday Evening Post’s “slush pile” of manuscripts in 1915 and began a prolific relationship between the satirical author and the magazine. Lewis’s novel Babbitt (1922) brought this kinship to a screeching halt due to its critique of business and the middle class. Lorimer wrote an unkind review of the book, and Lewis was left out of the Post for years to come.

In “The Other Side of the House,” a Minnesota trainman initiates a peculiar courtship with a student along his route. When they finally meet, one high-stakes decision to stay or go will set them on track for love or loneliness.

Published on November 27, 1915

This is a free country and everyone has the right to form a society to demonstrate what is wrong with the world. Members are hereby solicited for an association to prove that all evils — except mosquitoes — come from believing in types.

For example: The capitalist thinks there is a typical workman who is faithless and shiftless — a sort of human cold boiled potato. The workman imagines a typical capitalist who spends all his weekends in a guarded Long Island castle, inventing new devices for grinding the faces of the poor. So we have strikes and editorials and other evils. Then the individual capitalist and the individual workman discover that they are equally interested in babies and baseball, and they call off the strike and go fishing together. Anyway, they ought to.

The one universal fallacy is that romance belongs to a type that lives at least five thousand miles away and has slimsy, damp yellow locks, and contracts rheumatism by playing little fiddles in the moonlight; but the new society will prove that romance is always here for our taking. It will publish a learned report about a brakeman running on the Ferguston Division of the M.&D., an ordinary young Scandinavian trainman named Chris Thorsten, with hair like oakum and a face as cheery and commonplace as the nickel badge on his cap, who, nevertheless, experienced such love as makes immortal the name of Dante.

Born in Joralemon, Minnesota, with a Norwegian father and a Swedish mother, Chris Thorsten was so free from a hyphen that he boasted of what our ancestors did in the Revolutionary War. What could a fellow be besides an American — and a railroader? Like most Joralemon boys, he was fascinated by the yards of the M.&D., that fairy highway with St. Paul at one end and the Pacific Coast at the other. He had a favorite engineer, who let him ride in the cab; and whenever he went up to the swimming hole he flipped a freight. Before he was twenty he was a brakeman in the freight service.

Chris had an imagination and he reveled in his curious new world, one hundred and twenty miles long and one hundred and twenty feet broad. He studied every house and field and ditch and tarpaulin-covered threshing machine, from Ferguston to St. Hilary. He could see only one side of things from the train; but whatever he could not see was satisfyingly mysterious to him.

Three miles from the town of Wakamin was a white cottage, partly hidden by a willow grove, but with one window visible, at which a curtain waved like a beckoning hand. He was sure the front yard of the cottage must be a garden, with Canterbury bells and hollyhocks instead of Joralemon’s favorite flower, the well-meaning geranium. Nearby was the equally inviting Farm of Windmills. Here the farmhouse was so nearly concealed by the enormous red barn that he could see nothing except its mansard roof; but that awed him, because it reminded him of the banker’s handsome residence at home. He enjoyed an intimate acquaintance with the Farm of Windmills, based on about seventeen square feet of house roof, one barn, one chicken run, crab-apple trees, and two large willows.

For a year he noticed casually that some sort of smallish girl was to be seen playing in the yard or talking to a man in overalls. Once he saw the girl reading on a platform built in the branches of one of the willows. Chris was a railroader, trained to register twenty impressions in ten seconds, and he missed nothing. The girl was reading a book; and for people who read books he had an exalted reverence. It was a big book. He wondered what it was — bound magazines or a dictionary, or perhaps poetry. He decided that it should be poetry — a copy of the Family Compendium of Noble Poetry and Good Prose Reading for All the Household, that lordly compilation which the Thorsten family used for propping open the kitchen door.

Reading poetry! Yet she was, he observed, only fourteen or fifteen. She was sitting Turkwise on crossed legs that were long and slim, and as curving as the leaf of a fleur-de-lis, in coarse cotton stockings that seemed from a distance too extensively darned for the princess of a mansard roof. Her hair was exactly right for a princess, however. Most of the girls along the line had prim pigtails or weedy tangles of uncombed locks; but round the eyes of the girl in the willow tree foamed a shower of brown hair, wavy and fresh-washed. She was eighty feet away and he looked for a moment only, but he could almost feel the elastic freshness of her hair.

As the farm ran back out of sight, past the train, the girl glanced up from her book and gazed off among the trees, her delicate chin in her hand.

Chris took with him the memory of her brooding quiet. He was nineteen and imaginative; and, though he did not know it, he was a railroad man because thus he approached more nearly to the world of cities and sea and old beautiful things than he could have done as a farmer or miller or clerk. He had told himself stories — not particularly original ones — about far-off, mountainous, shining places and about misty-haired girls, ever since as a boy, lying in the old black-walnut bed in the Thorstens’ attic, he had listened to the distant whistle of the trains. Into the musing of the girl in the willow he insisted on reading a proud fineness that was rather noticeably lacking in the bouncing, giggling girls who hung about the stations to see the trains come in.

He saw her nearly every time the train passed the farm; saw her reading other books in the willow, or making believe, as few girls still dare to do at fifteen. Once she was sitting on a wooden kitchen chair draped with a Turkish portiere, wearing a pasteboard crown and languidly waving a scepter, which must recently have been the plunger in a patent washing machine. Once she was a knight, wearing a washboiler cover on her back and riding a bewildered old horse, which could not understand that she was trying to make him charge on the chicken house.

Though he waved his hand at the children who came out to watch the train go by, he dared not wave at the girl of the Farm of Windmills. She was sacred; he identified her with dreams and put her in a place apart. Some day, he felt certain, he should miraculously meet her; he would speak to her in a high-flown antiquated manner, like the magazine stories about pilgrims and tapestries, with words like withered roseleaves. He would not say Gee! to her; nor Gosh! — not once.

For two years he watched her grow up. He saw her dresses lengthen, her shoulders straighten, as she passed through flapperhood — a little, light-stepping image of coming womanhood. In winter she came from the white schoolhouse; and he was jealous of the louts who carried her books or threw snowballs at her. Sometimes she waited at the grade crossing for the train to pass, and her delicate cheeks were touched to color by the cold, as sunset makes rosy the snow. He knew all her gestures, and from them knew her soul.

During these two years Chris’ mother died and he moved to a barren boarding house in Ferguston. He met few people there, and gradually the girl of the farm came to be the person whom he knew better than anyone else in the world, though her name, her voice and her thoughts were all unknown to him. And she was not merely his friend, but his guide. Had he been living shoddily she would have regenerated him. Chris was technically a good young fellow. Yet he did waste too much time over Kelly pool; he spoke muddy English; and it was mostly in his imagination that he did all this reading of which he was so proud.

Now, under her silent influence, he laboriously dragged himself through book after book. He made jerky, youthful efforts to speak quietly, move graciously. With youth’s faith in itself he cheerfully started out to become entirely perfect, so that he should be ready to meet her. Every time he cursed — he cursed, all right; you do, if you hook up cars on a slippery track — he blushed exceedingly and thought of how hurt the girl would be. He was very sentimental. Yet he was a promising young brakie. Not the great John Gorman himself could open a switch more quickly, though John was mighty among brakemen.

The third summer, when the girl made-believe no more, but, with her dress properly tucked in about her ankles and her head resting on her hand, read and read in the hammock under the willows, Chris began to think of her as not merely a playmate but as a woman whom he loved man-wise. She must have been eighteen; a white little princess. He fancied that her arms, as she bared them in work about the barnyard, were fine-textured as silk.

Then, in September, she disappeared from the farm. He watched for her anxiously and for two weeks would not admit that she was gone; but he imagined dreadful things. She was old enough now to be married. Perhaps some man whom he had never seen, some perspiring, heavily jocular citizen of Wakamin, had taken his silver girl. Or was she sick?

He saw her, at last, at a distance, on a street in Joralemon. He casually asked his old friend, the all-knowing bus driver, whether that girl was not the daughter of Doc Lingard.

“No,” said the driver; “she’s some girl from out of town that’s going to high school here. Don’t know her name.”

Chris was vastly content; very proud of her. He decided to attend high school with her. His own schoolwork had ended with the eighth grade. He solemnly bought the books for Freshman and Sophomore classes and turned his room at Ferguston into a private school, sternly conducted by Professor Chris Thorsten, evenings, when he was back from the road.

He read history, algebra, physiology; and in Tennyson’s Idylls of the King had reason to suppose that his fantastic love was not necessarily so idiotic as John Gorman, the swing brakeman, would have maintained. He became so precise in speech — so nearly precise — that Gorman jeered: “Gosh! You must have swallowed the dictionary.” And Chris had to throw in a few “hells” to show that he meant no insult by trying to speak correctly.

He pretended that in his town, miles from her, he was actually studying with her, sharing the same book. He could feel one elbow grind on the table; feel the other arm, as he turned the leaves, faintly touch her side. The light would slide down her smooth cheek to her throat as she glanced from page to page, he imagined.

It was in his high school reading that he first learned the story of Dante — which he innocently pronounced Dant. He traced himself in the lonely poet; the girl of the farm in the deathless Beatrice. All winter he asserted to himself that he was the exiled Italian, wandering down the damp corridors of ancient palaces. He was not, though. And the Minnesota winter was not really a season of rains and poetic melancholy.

Chris, on the cars, was a lumpy figure in a duck-lined Mackinaw coat and huge red mittens. Two cars away he could scarcely be seen through the blizzard. When the northwest gales stopped, and the sun glared on miles of snowdrifts that stretched from the track to the steel-blue sky, the thermometer dropped to forty degrees below zero and the coupling pins stung his hand even through mittens. But he was Dante and also a high school prize winner, and declined to admit that he was cold.

It is probably true that Chris Thorsten’s poetry was inferior to that of Dante; but, as regards practical common sense, he was a genius compared with that self-satisfied, wireless lover. He knew that if he was ever to care for the girl he had to climb beyond brakemanhood. He saw no reason why he should not be General Traffic Manager some day; but he saw plenty of reasons why he was not likely to be, unless he got into the General Offices — which the railroaders call the white-collar route. He added stenography and typewriting to his studies, and read books — one book, anyway — about railroad finance and management.

The girl seemed so constantly with him that for a second he was not surprised when, on a May day — with the poplars and silver birches in foliage, the prairie sloughs like fields of bluebells, and lady-slippers out in the tamarack swamps — he saw her again, standing between the willows, at the Farm of Windmills. Instantly his hand shot out as though it was a live, winged thing flying to her. For the first time in nearly four years of a love like worship he was waving to her. She responded — a flick of her hand; a slight turning of her shoulders in her white blouse; while the sun caught the movement of her piled brown hair.

He stretched out his arms, standing on a box car, revealed to her as a figure against the cornflower sky, in the attitude of crucifixion — and of utter happiness. His floppy corduroy trousers and black sateen shirt and black slouch hat fluttered buoyantly as the breeze whisked about him.

He wanted to tell someone all about it; but — the conductor chewed tobacco, and the front brakeman wore a celluloid button stamped, “Kiss me, kid!” and John Gorman had a laugh like a sick horse. Chris compromised by shouting, “Great day, by golly!” to the operator when they reached the Wakamin Station. By which he meant to indicate that the year was at spring and his sweetheart slim and winsome and kind; that life was exciting and the Wakamin Station more glorious than all the stations of London or Rome or fairyland.

In this last he was absurdly exaggerating. The Wakamin Station presumably answered the purpose, but it was not esthetic. On the splintery platform, so sun-soaked that the planks smelled of pine forests and resin oozed out in amber drops, one case of empty beer bottles reposed desolately. Under the platform all the homeless newspapers and orange peels of the neighborhood found a resting place. Yet here Chris shouted his happiness.

He waved to the girl again the day following. She did not respond. The third day she was not in sight. The fourth, she fluttered a handkerchief at him. The fifth, she was reading in the hammock and did not look up. The sixth, he was off duty. The seventh, she did not appear. The eighth, she answered with a gesture of her delicate fingers like the waver of lace in a draft.

So it went for two weeks, and he tried to assay her replies scientifically.

Once, when they were sidetracked for two hours, John Gorman caught him plucking the petals of a daisy and growling: “Loves me — loves me not!” Chris had to lie vigorously — that he was trying to guess his chances of winning Doc Nickerson’s shotgun raffle — to save himself from the reputation of being a young lover.

There is probably no legal reason why all lovers should not be confined in asylums. For more than two weeks it did not occur to Chris that, though he knew the girl better than he knew any other person in the world, and though she had waved to him, yet there was no reason why she should distinguish his greeting from any other careless gesture by a passing trainman.

When he did forget moonshine long enough to make this revolutionary discovery, he spent an evening at Ferguston in composing a bouquet for her. He discerningly stole daffodils from his landlady’s garden, and from Old Man Bromenshenkel, the vegetable man, he bought irises, purple and golden; and he wrapped the bouquet in silver-gilt paper, with all of the lover’s fumbling anxiety over his first gift. Thrice he unwrapped it — once to see whether the stalks were fastened, and once to put in a note, “Greetings from a lonely brakie!” and once to remove that note, which he rended and utterly destroyed.

Next day it was his trick on watch in the caboose cupola. He thrust his arm — unromantic in its sleeve of blue flannel fuzzy with lint — through the window, whirled it violently, and let the bouquet fly toward her. The girl, not very poetically engaged in feeding pigs, stared perplexedly and did not give response. The bouquet landed in the weed-filled ditch beside the track.

When the train passed next day Chris saw the gilt paper of his gift still lying among the weeds, a forlorn thing, with the gay cover smashed from its fall.

Hurt, amazed, he stared at it, then peered at the farmyard. As in her childhood days, the girl was reading on the airy platform among the willow boughs; but round her slim, fine legs a long skirt was swathed and her fingers pressed her temples as though her eyes were a little tired.

She looked up, the sunlight that came through the leaves checkering her hair with light and shadow, and let her quiet glance dwell on the train. He curtly saluted her, hand to forehead, and she waved just as the train exasperatingly bore him away.

“I wonder whether she knew it was a bouquet for her?” he meditated.

That night he prepared another bouquet of the brightest irises he could find, and he flung them unwrapped. He saw her pointed chin rise until her throat shone above her collar as, with surprised eyes, she followed the arc of the flying flowers. She started to run forward.

The flowers were gone next day, and from the tree house she peeped shyly at the train.

Roses, as they came into bloom, sweet peas that were like her fresh cleanness, pansies and peonies, he gave her. He had to hide them in his lunch pail, in his pocket — even among the farm machinery loaded on flat cars — to conceal them from the other trainmen.

She was standing by the fence one morning of passing; her fingers were nervously pinching the rusty barbed wire; with a perturbed, lovely excitement she was examining the whole train. He was impudently perched on a brake on a box car. He sprang up; his hat came off. His cropped, broom-colored hair and the pleasant evert tan of his Norse face had something of the sturdy boyishness of a young knight. He awkwardly bowed to her, and from his pocket he brought out a careful though slightly mussy little bunch of pansies. A smile transformed the searching seriousness of her face; then, as though she were again the little girl, she ran away.

She waved to him always after that. Once or twice there were girls with her, visitors apparently, and she motioned with a secrecy that she evidently enjoyed. He saw her studying him from the willow, her little high-crowned head cocked on one side.

He knew now that her greetings were for him alone. Once, when he was in the cupola, he saw the front brakeman signal to her. She stared at the intruder and did not move; but when the caboose came opposite her, and Chris waved, she was like one waking from a brown study.

At last he sent her a book by his aerial post — Keats’ Poems, in a red-line edition — and in it this note:

Please let me send you this book. For years now I have been watching you read; I guess there are not many girls along here who read. I love to read too; even a brakie loves to read sometimes. I read Dickens and Hall Caine, and lots of magazines. So I wanted to send you this book. If you like it just wave it once as I go by, and I will know I have not been fresh in giving it to you, because we both like to read. Honest, I do not want to be fresh. I have got all kinds of respect for the lady who reads such interesting-looking books in the willows.

YOUR FRIEND OF THE FREIGHT TRAIN.

P. S. The librarian of the Saint Hilary Public Library — she is a highly educated woman — says she is sure you will like this book. It is fine poetry. I do not read much poetry myself, but I appreciate it.

He was gloomy after giving her the book. Perhaps she would scorn it. He pictured her with eyes flashing, foot stamping — like the heroine of Humble Hearts, which had played under canvas at Ferguston; he fancied her exclaiming: “Sir, how dare you!”

Next day she stood at the fence again, flushed, agitated, her eyes shining. As he came abreast of her she pulled the book from under her arm, hesitated, then waved it timidly.

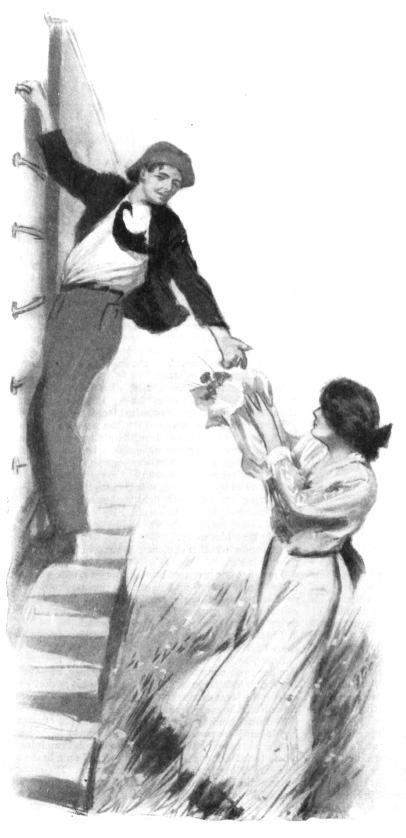

After two weeks, during which she did not come so far as the fence, though he sent her another book, he looked ahead and saw her down beside the track, balancing a ball of paper and watching intently. She motioned up at him with the bundle. He skipped down the iron ladder on the side of the box car and leaned far out, precariously holding the ladder with one hand, the other hand outstretched toward her, smoke and cinders storming round them both.

The train roared forward; he was carried toward her — was for the first time near her parted, expectant lips. She was holding out the bundle. He caught it, slammed it to his breast to hold it safe, while in the sudden jerk of the action he almost lost his grip and nearly fell from the ladder. He heard the cruelly grinding trucks. His whole body contracted with the fear of falling; but instantly he got hold of himself and over his shoulder bowed to her gracefully — that is, as gracefully as a man hanging with feet and one hand to a ladder on the side of a jouncing train, swinging with the motion, can reasonably be expected to bow.

As Dante would have opened a scroll from Beatrice, so a panting, dusty brakeman sat on a box car and undid the folds of a bunched newspaper.

There were shaggy russet dahlias setting off the purple of wild asters — and among the flowers this note:

Dear Unknown Friend:

Indeed I do love to read books, as you said; and I want to thank you many times for making my summer happier. It might have been quite a lonely summer if I hadn’t had somebody to sort of talk to as you went by. There are not many books round here, so I appreciated your thoughtfulness; and, oh, indeed, I did not feel you were fresh, like you said. I am going back to school. I leave this afternoon, but could not go without thanking you. I hope you will not have a bad winter; it must be hard on trains in snow. I will think of you there.

THE GIRL THAT READS.

“I will think of you there.” That was the phrase he kissed most frequently.

He studied her handwriting — the precise script of a woman who reads much and writes little. In the slender loops of the l’s he saw her own self.

She was gone; autumn had come. Two months later he was promoted to brakeman in the passenger service. He took up more keenly than ever his stenography and science of railroading and high school work.

At the Joralemon Station he saw a poster advertising a high school entertainment. His passenger run ended at St. Hilary, forty-odd miles from Joralemon, and he was tired when he reached there at 5:30 p.m.; but he caught the seven-seven train back to Joralemon. He saw her among the group marked by their silver-and-maroon banners as Seniors. Apparently she was completing her high school work in two years. He ached with the pride of that, and with his glory in her when she stood out in a frilly gown of white mull with lace insertions, her hair in a pompadour, and sang Oh, Promise Me! as a solo.

It was the first time he had heard her voice. It was deliciously cool and young; in it was the sound of evening leaves.

Perhaps she would have seemed to the outsider, to the believer in types, merely a lithe, clean, rather pretty girl, in a provincial frock, singing a fair schoolgirl soprano; but her public appearance added awe to Chris’ love.

Another May day — and she was back at the Farm of Windmills.

She could not know that he was in the passenger service. He ran down to the steps of the open platform, pulled off his semi-military cap, waved wildly. She stared for a second — lovely and dreaming among the crabapple blossoms — and broke into quivering life as she waved back.

Most periods in all lives are times of drudging along day after unchanged day; of wishing that something surprising would happen. Such was that summer to Chris. He threw flowers to her and a few books; he knew the daily sweetness of seeing her and the daily agony of not hearing her voice. But nothing happened.

He was on the train bound south one hot September afternoon. He was opening ventilators and had stopped to talk with the Ferguston undertaker. He lolled on the arm of a seat near the front of the car, and as he talked he looked along the aisle. He saw a silk-clad ankle, sleek and smooth as a pigeon’s breast, a girl’s foot in a dull-leather pump, and the flounce of a blue skirt. He glanced up casually. His heart leaped! The girl — the girl! — sat four seats away, on the other side of the car, facing him.

She was transformed in a town suit of blue cheviot, and the stiff linen collar of that period contrasted with the girlishness of her demure head and ivory neck. She was looking away from him, her face in profile; he saw the wistfulness of her lips, the uptilt of her chin. She seemed — to him, at least — altogether a city girl, and the timorous deference of the small-town man to city clothes accompanied his noble deference as lover.

He was weak about the knees and wabbly at the pit of the stomach. He did not dare go down the aisle — speak to her. What could he, an ordinary trainman, say to the goddess? He fled to the baggage car, where he informed John Gorman, acting baggageman, that he had a peculiarly violent headache… Suppose she expected to see him on the train? Suppose even that, by a miracle, his absence disappointed her? Better that than reveal himself to her as a boor!

He looked out from the baggage car at each station. He saw her leave the train at Saint Sebastian and take the bus for the State Normal School, where the young ladies of Moore County are trained in fudge making, tennis, and the teaching of the young.

The winter was lonelier because he could not get himself to peruse Needlework, or the Organization of Beneficial Recess Play, with Lectures on the Planning of School Playgrounds, which were among the courses scheduled in the Normal School Catalogue. He could not pretend now that he was studying beside her.

He so savagely regretted not having spoken to her that he would start up from his chair to go to her. Next time, he swore to himself, he would be prepared to meet her. That motive became a religion, though he did express it by making foolish memos on report blanks — “Read poetry. Learn conversation. Mem. — Get new neckties.”

Spring! She was back! At last Chris told her something of his long devotion — in letters to go in books. As he wrote each letter he planned to go and see her at the farm; but it was quite suddenly, and for no visible reason, that he decided to take a lay-off the following Friday, deadhead to Wakamin, and drive down to the farm. He would at last explore the other side of all the houses he knew so intimately from the one side — see the old-fashioned garden in front of the white cottage; and see —

He did not know even the name of the girl. He would learn it now.

A tremendously bathed and imperially shaved and quite incomparably hair-brushed Chris, in a new civilian suit of ready-made blue serge and a stiff and shining new purple tie, hired a buggy at the Wakamin livery stable. The road south was dusty, but meadow larks sang on the fence posts, the wild roses were in full bloom, and the wheat had spread its exquisite pale green over the rolling prairie. Half a mile from Wakamin the road began to parallel the railroad track. Chris recognized the other side of things he had known for years. He was excited to find that the back of the World Harvester Company’s lone billboard concealed a pile of scantlings. He gasped:

“All these years I’ve seen that sign and I never knew there was anything on the other side!”

He was growing too feverish even to note farms that had always been hidden from him by woods. He would see her — now! What would she be like? He pulled the horse down to a slow walk. He had to get hold of himself. So he came creeping to the house just preceding the Farm of Windmills — the white cottage of the hollyhocks — only there weren’t any hollyhocks!

He had so clearly pictured the bright, prim garden which must flourish in front of the cottage that he stopped the horse and stared about to get the landmarks before he would believe that this was the cottage. It was. But as for the garden his imagination had filled with charming idlers — he beheld a dooryard of trampled flowerless earth, a litter of tin cans, a pigpen slushy with mire, mud spattered over the door, and a woman, shouldered and breasted like a man, slovenly in calico faded from blue to a weak white, wearily mauling clothes on a washboard.

He felt — literally — that he had been betrayed. He drove unwillingly up the hill that separated the cottage from the Farm of Windmills. Halfway up he stopped again and gave way to wretchedness. Would the Farm of Windmills — and the girl — disappoint him as the white cottage had?

He dared not top the rise — whence he could see her farm — and take even one glance. He slowly turned and lashed the horse toward Wakamin. He looked straight ahead at the road. He paid no attention to new aspects of the route. He did not believe in the other side of things — so he told himself that afternoon.

He waved to her daily afterward, but he did not send her flowers or books or letters — save once, when a week of rain, gloomy with approaching autumn, made him so lonely that he had to tell her how much he needed the comfort of seeing her. She came out in the rain almost every day; but he doubted himself now — he wondered whether she came out for him or because she was so bored that a passing train was a relief.

He was rolling down the car aisle somewhere south of Wakamin. He stopped dead — before a seat in which sat the girl. He had met her!

She was alone. She was staring straight at him. Her shoulders were thrust forward. Intensity was in her face. The fingertips of her right hand were pressing hard on the red-veneered seat arm — the hand like a wild thing, crouching, cowering. Very serious and somewhat frightened was her look. Chris stood, with palpitating heart, his mouth slightly open, his arms checked in mid-swing; so that one hand was held drooping in front of him. One leg remained bent at the knee, the foot poised on its toes.

For ten seconds they stared. He bowed, frigid with embarrassment. He could feel the vertebrae of his neck crackle with the stiffness of his bow. His absurdly outthrust hand fell to his side. All he could think was:

“Gee! How did she ever get on the train without my seeing her? Why, I never saw her at the station! Gee! That’s queer!”

She turned her head; looked away from him, through the window. He started forward, his head angrily high; yet he was unable to keep his eyes from her. Before he had quite passed she turned back to him, with a smile infinitely shy, a smile that begged him not to misconstrue its timid friendliness. He muttered:

“Oh, y-you’re g-going back to normal school. It’s — Jiminy, you’ve got a hot day for it!”

“Oh, yes; it is hot.”

Perhaps the words were not memorable, but her voice fulfilled all he had hoped for — a vital sweetness; youth’s passion for life. He was aware of its magic, though this was his addition to the brilliant conversation:

“Yes; sure is!”

He damned himself for talking to the true goddess about the state of the weather; but he could get himself to speak of nothing else. He was obsessed by the fact that she was wearing the same blue cheviot suit as a year before, though it was shabbier now, a sleeve flashing shiny underneath, as she raised her fingers to pluck nervously at her collar. A cuff had been darned with painful care.

He knew love’s sorrowing pity — that she, who was sacred and of fine silver, had to make secret economies; but it put her more on his level of plain human being, and as she nodded to his ridiculous “Sure is!” he sprang into real speech:

“Gee! It’s awfully hard to know what to say. Honestly — you’ll think I’m just a small boy if I tell you” — her smile was reassuring — “but I’ve planned for years what I’d say when I met you. All sorts of Smart-Aleck things. And now I can’t think of a single one of ’em!”

“I know!” He dropped on the seat arm beside her. “I know how it is,” she said. “I’ve wondered about you. I — I want to thank you — flowers and everything.”

“Oh, they weren’t anything. We’re coming into Joralemon — got to go out on the platform. I — oh, I don’t want you to think I’m forcing myself on you; but it’s just like I’d known you for years. And now you’ll be gone — all winter — won’t see you. But if you do think it ain’t quite proper for you to talk to a stranger — Oh, let me come back!”

In a voice thin and hesitating as a flute she said:

“Yes; come back.”

She flushed glorious red over her cheeks and throat, which above her low collar was bright and bare. She glanced away from him, down at her rattan suitcase.

At the Joralemon Station John Gorman came snickering up to Chris:

“Pretty little dame I seen you with. Takes a squarehead to pick out a good looker!”

Chris answered with terrible quietness:

“If you butt in, Jack, I’ll just nach’ly kill you!”

“Well, you don’t need to get so huffy about it. Who’s butting in?”

Gorman clumped away. Chris did not look at him. He was pantingly trying to decide what he dared say to the girl. He hastily outlined a number of remarks, good, sound, sensible remarks, about Keats and Dickens. As he reentered the coach he forgot them all in the thrill of actually having her there.

Some place between the station platform and her seat he conquered youth’s inability to face a big thing directly and seriously without capering. He had only one hour between Joralemon and Saint Sebastian Normal School. He came to her in a matter-of-fact way, and sat in the seat beside her. He said gravely:

“We haven’t much time. Can’t we tell — can’t we — ”

“Trust each other?”

“Yes!”

“I’ll try to.”

“Please do! Not spar ’round like a man and a girl flirting.”

“Oh, we must! I am going — I’m not going back to the normal school. My mother died when I was a girl and my father died last winter; and we haven’t very much anymore. My brother and I are selling the farm — what’s left of it. I’m going down to Nebraska, where my brother lives — to stay. I’m going to teach country school there and live with him.”

“Then I won’t see you at all next spring; not at all — not even then?”

“I’m afraid not.”

“Will you miss not seeing me next summer — a little?”

“Yes; I’m afraid I will.”

Her voice was so low he could scarcely hear it. She stared through the window again. For a second he laid his hand on hers, which rested nervelessly on her knee. Her hand was a holy thing, yet now he had the courage to touch it; she had spoken so forlornly that it would have seemed natural to take her in his arms and comfort her.

“Honestly, I’ll be — I don’t know just how to put it,” he said. “I don’t know how to tell you how glad I am if I have made the summers happier — Oh, I’m just talking words! All I can think of is, you’re going away from me; maybe never come back. Why, six or seven years now I’ve never gone by your farm without looking for you. I’ve imagined — Oh, I know you so well! I’ve watched you read and play and work; and then when you went to Joralemon I imagined you studying there

“How did you know I was there?”

“Saw you on the street and asked about you. Why, do you know when I found you were in high school I took up history and geometry, and the whole caboodle, so’s to be with you?”

“I don’t know — how did you take them up?”

He explained. He brought into the noisy car something of the white nights on which the girl and he had studied side by side. She listened, hesitated, answered:

“I guess maybe I’ve sort of made-believe about you too — ever since you first waved to me. I pretended you were my courier — like in a fairy book; that you brought me messages from abroad to my castle on the hill of glass. And then sometimes I thought of you as a railroad man; but I imagined you going clear out to exciting Western places. Once I got a timetable and learned the names of some of the places in Dakota and Montana where I pretended you went every day — names that made me fancy things, like Big Sandy and Galion and Wolf Creek and Silver and Homestead and Antelope. Is it very silly for a grown-up woman to make-believe? Think! I’m 21 now!”

“Why, honey, it just means that you and I have stayed kids instead of getting stupid. I guess I’ve always been waiting for you to play games with. So I’ve always been — oh, always been kind of good and — Oh, thunder! I don’t know how to say it without making it sound sissy.”

“I know… Oh, please tell me — tell me honestly: Am I doing wrong in talking to you like this? I did — I’m confessing so much that it scares me; it isn’t ladylike, I guess, but I have to — I did want to talk to you before I went away for the last time. So I took this train — intentionally. Was that wrong?”

“Honey, all I know is that if you hadn’t spoken to me I would have been so darn miserable for years — I never would have known where you had gone, or anything. I wouldn’t have had anything to live for. Oh, you couldn’t have done that!”

He caught her hand; his fingers interlaced with hers, disturbingly conscious of the softness of the flesh between her fingers. He looked at her piteously. As her voice, her fine brown eyes, everything about her, had told him she was indeed the girl he had hoped for, so perhaps something of the clean and dreaming boy who had devoted his soul to her worship was revealed in his Norse eyes and frank face. She did not withdraw her hand. She murmured:

“I worried about it all terribly; but I couldn’t go away without speaking to you if — if you wanted to.”

“You must know — look at me, dear! You must know how much I wanted to. Don’t you know?”

She did not answer. She glanced shyly at their linked fingers and tried to pull her hand away; but he held it tight, while his thumb stroked the silken warm hollow between her thumb and first finger. She peeped uneasily over his shoulder, as though she were afraid someone was watching them. Gradually her eyes came back to his, and she admitted:

“Yes; of course I hoped you might care.”

“I did! Honey, see here! We’ve — what is it they call it? — we’ve started fencing now. We mustn’t. Think how much we’ve got to do in such a short time. My division ends at Saint Hilary and we’ve got to get acquainted before then — and every so often, I guess, I’ll delay things by getting scared to think that I’m actually sitting beside you and talking to you. To you! Tell me — oh, tell me all about yourself.”

A quick scuttling to cover is more characteristic of lovers than is frankness; but the pressure of time kept these babes in the woods from the unhappy evasions and recriminations with which most lovers fill up evenings for a year or two.

They bravely started out to probe each other’s soul. They spoke with a most commendable gravity of books and music. She asked him who his heroes were and he was immensely pleased with himself, because he had thought that out long before and could answer offhand: “I admire Jim Hill, because he’s a great railroader; and Dante, because he was a great lover; and Lincoln, because he was a great man.”

They really made a creditable effort to be lofty and impersonal according to the best standards inculcated in the normal school; but he would be asking: “Were you glad the first time I waved to you?” And she would inquire: “Were you excited when you saw me standing down there right by the train, with a letter for you?” Such important topics as the church he attended, and what she really thought of the aesthetic value of Mademoiselle Mary Pickford of the films, were frequently sidetracked by such interruptions as this: “Oh, sa-a-ay — tell me: What is your house like in front? And I’ve always wanted to know whether that brick building is a milkhouse or a smokehouse.”

Their eyes held each other. He touched her hands, marveling:

“I can’t believe you’re really here; that this is — But, gee! I knew your hands would be like this — fingers sort of pointed. And I always did think your eyes would be like maple trees on an October afternoon — and they are! Gee! I’m almost as bad as one of these here poets; but I can’t help it.”

“Oh, you mustn’t!” she whispered and listened for more.

He had to leave her at each station, but their talk hung suspended, like a hummingbird over a honeysuckle. His absences made them more conscious of the cruel race that time was running with them.

The barren outskirts of Saint Hilary approached. It seemed as though the passing country was galloping faster and faster, to terminate their hour of glory. With a hectic urgency he demanded:

“We’re almost at Saint Hilary. The train changes crews there. I have to get off. We can’t separate now! We’ve been waiting for this for years — I have, anyway. I’d go on to Minneapolis with you, but I’ve got to go out on an extra run tonight; several train-men on the division sick. There’s — How much time’ve you got in the city before your train starts for Nebraska?”

“About four hours.”

“Then listen! You get off here at Saint Hilary. I’ve got about three hours before I start out again. Two hours from now there’s a train on the Grand Pacific — parallels the M.&D. to Minneapolis. You’ll have plenty of time to catch your train this evening. I know the G.P. crews and I can deadhead you through.”

She looked curiously shrunken, smaller and younger, in her alarm.

“Why — why — I couldn’t — ”

“You could! Quick! Darling, think quick! You’ve known me for years. Look at me! No time to be polite. We’ll regret it all our lives if you act like a prissy schoolma’am. Do I need to swear I’ll protect you? Look at me! You know this is the biggest thing in your life, like it is in mine. I can see it in your eyes. Come!”

She was crying, her fingers pressing her throat until the flesh round them turned from even brown to blue-white. The train was entering the Saint Hilary Station. She had not answered.

“Quick!” he begged. “Won’t you be lonely for me — ’way off in Nebraska? Won’t you remember my flowers? There won’t be no one that I’ll want to throw flowers to!”

He stooped for her suit case. He seized her hand — its small whiteness disappeared in his hard paw as though it had been swallowed.

She wearily rose. He guided her down the aisle.

They stood on the station platform, shy, awkward, with nothing to say, as the train pulled out. Once she started toward it. He put his hand on her arm gently and she stopped, still eyeing the train. As the last car fled from them, its rear door and windows like the square nose and eyes of a leering face, she peeped at him, deprecating, appealing.

“Gone,” he said. “Sorry?”

“No, not now… It was mean of you to remind me of the flowers. What could I do after — What is your name?”

“Chris Thorsten. Honey, you aren’t afraid now, are you?”

“Not anymore, Chris — dear. You’ve made me pretend about you for so long now, that I guess you’re my oldest friend. And don’t you want to know my name?”

“Oh, your name. Oh, that’s all right, we’ll change it!”

She nodded absentmindedly, then blushed so furiously that she could scarce answer when he added with sudden laughter:

“Gee, I’ve clean gone and forgot to propose, and all along I’ve been intending to propose very next time we met.”

His laughter was that of a man who has found glorious happiness — not of a wistful boy nor of a morose Dante.

You can see for yourself, he didn’t live ’way off in Arcadia or Japan, so of course he wasn’t a romantic type.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now