Was the American dream no more than a dream after all?

When James Truslow Adams coined the term, he was describing the belief that America offered a better, richer, and fuller life for everyone “with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement.”

In other words, the opportunity for a better life would be based, in part, on your personal accomplishment. This has traditionally been expressed as “work hard and you’ll succeed.”

Adams introduced the “American Dream” in his book, The Epic of America. It was published early in the Great Depression, when the American Dream had fallen on hard times. Personal achievement hadn’t helped millions of Americans who’d lost their life savings because of strangers’ speculations on Wall Street.

Yet many Americans believed — and still want to believe —their hard work will be crowned with success. Many, however, have lost faith in the Dream.

Wages have stagnated. Housing costs are rising faster than wages. A recent poll found 74 percent of Americans believe that poor people work hard but are never able to escape poverty. While hard work may affect your success in America, so will many factors beyond your control, such as your race, gender, parents’ income.

And factors that you can control — such as education — can create other burdensome obstacles to success. Today, a college education has become extremely expensive. Over the past 30 years, tuition has doubled at private colleges and tripled at public institutions, to hover near $10,000 for the 2017-2018 year.

Yet college appears crucial for success. On average, students who only complete high school will earn half or a third of what their peers who attend college will make. Over the course of a career, this salary differential might justify the nearly overwhelming debt it places on young college graduates. But even with the additional earning power a college education affords, default rates on student loans continue to rise.

But a college degree may not be as much a determinant as your race. Recently, economists at the Federal Reserve Board calculated the odds of becoming a millionaire for middle-aged college-educated Americans in four different racial groups. They found the odds were:

- 22.3 percent for Asian Americans

- 21.5 percent for white Americans (37% with a graduate degree)

- 6.8 percent for Hispanic Americans

- 6.4 percent for black Americans

In fact, a middle-aged black man or woman with a master’s or Ph.D. has about the same odds of becoming a millionaire as a white person who only completed high school.

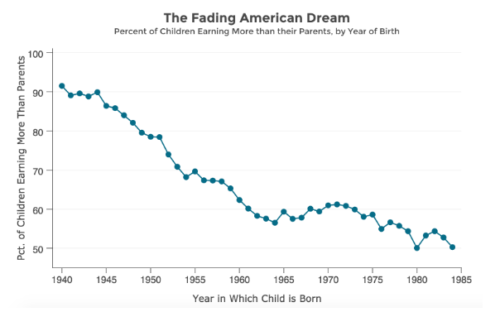

Two more factors can affect your success: the economy and where you live. This was illustrated by a Stanford study that showed the falling odds that workers in Michigan — a state hard hit by the decline in American manufacturing — will earn more than their parents did at the same age, adjusted for inflation. In 1970, they had a 97 percent chance of out-earning their folks. By 2010, the odds had dropped to 46 percent.

With so many factors lowering the odds of success, what can raise the odds? There’s hard work, education, and talent. There are also a number of small factors that may influence how potential employers judge you.

For example, using the middle initial of your name increases the chance that people will favorably judge your intellectual capacities and achievements.

Also, people with “easy-to-pronounce” names are evaluated more positively than difficult-to-pronounce names. And women with masculine-sounding names will have more successful careers in law than women with feminine names.

The month you were born seems to affect your chances of becoming a CEO. The number of CEOs born in June and July is small relative to the number of CEOs born in other months, and is likely related to school admissions grouping. (In other words, the youngest kids in a classroom are beset with disadvantages that follow them their entire lives.)

And then there’s “luck” — incidents of good fortune. Unfortunately, luck isn’t dependable. Nor is it fair, since it appears to come more often to people who’ve had good fortune before. When scientists studied patterns of success in a sample group, they found that, over several decades, nearly half of all successful events occurred for a small minority of the group. More than half had experienced no good fortune that noticeably altered their lives.

Nearly a century ago, young Americans were also wondering about their odds of getting ahead. Saturday Evening Post writer Albert W. Atwood addressed the question in “What Are the Chances of Success Today” in the June 12, 1920, issue.

He began with the faith that great success would elude most people. They didn’t have the physical, mental, or moral qualities needed to become managers or business leaders.

For those that did, though, Atwood quickly dismissed the traditional hard-work formula. “Merely hard work is not enough to get one ahead. The harder a man works, the more the company is willing to pile on him, and nothing satisfies the company more than to have him remain in the same position.”

The problem with the simple formulas for getting ahead in your career was that they didn’t apply to the modern workplace. The nature of work had changed by 1920. The typical employer was no longer a small manufacturer but a large corporation where men and women were easily overlooked.

Atwood urged the ambitious to find ways to distinguish themselves among their co-workers. In a crowded, distracted, highly competitive market, ambitious workers needed to put themselves forward and sell themselves to their superiors. And this often meant taking an unconventional, unexpected approach.

“Attract the attention of a superior,” Atwood wrote, “show initiative. With large corporations more initiative is needed break out of the rut. Most of the workers are too far down the line to be seen.”

The unconventional approach was also true for people starting a career. One business leader told Atwood, “If I were a young man and wanted to enter the railroad business, and if I had a few hundred dollars or my father had some money, I would not take a job on a railroad, but I would go abroad for a few months and write a book or a series of articles on railroad conditions in Europe. I could attract more attention in the railroad world in that way immediately than I could by years of hard work.”

Whatever the rules of success had been in the past, Atwood wrote, they had changed in modern America. “The man must [find] chances of advancement for himself and take advantage of them. He must show the company… he is worth more in some other position than in the one he is holding today. Until he can do that he will not get anywhere.”

In other words, it’s not enough for you to accomplish miracles of industry. Success requires you to make certain your employer knows your worth.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now