It’s been 100 years since the influenza pandemic of 1918 — which wasn’t the first nor last. Three more flu pandemics have struck since then — in 1957, 1968, and 2009 — though none were nearly as deadly.

A century later, researchers know more about the virus — how it spreads, how it kills — and have developed better tools to detect, prevent, diagnose, and treat the disease. While we now have successful vaccines that protect against measles, mumps, rubella, and other diseases, the effectiveness of the annual flu vaccine — to date our best protection — varies considerably from year to year. As a result, the constantly changing flu virus all too often slips by our best defenses, leaving us vulnerable to infection.

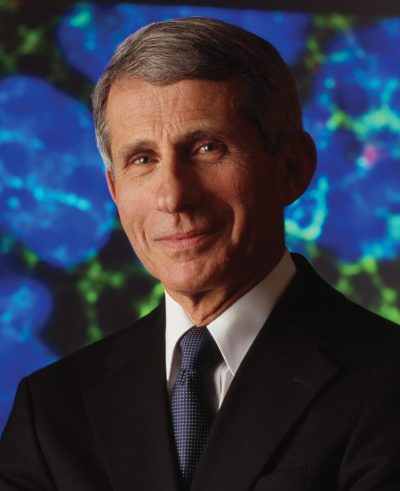

The Post reached out to the nation’s top expert on infectious diseases, Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, for an understanding of what makes this particular virus so deadly and to learn about solutions that are coming down the pike.

Patrick Perry: Science has made so much progress in developing vaccines against polio, measles, mumps, and rubella, but not flu. What is so unique about the flu virus?

Anthony Fauci: The influenza virus is a complex human pathogen with multiple subtypes and strains, and very different from other stable viruses, like measles, that change little. The measles that I got as a child is essentially the same measles in the vaccine that I vaccinated my children with. Once infected or vaccinated with the measles virus, the body mounts an immune response against the virus, and that immunity is essentially lifelong. Unlike measles, the influenza virus is a moving target, constantly changing in one of two ways — what investigators call antigenic drift and antigenic shift.

PP: What happens when flu viruses drift or shift?

AF: Drift refers to minor changes in an influenza virus from season to season that may produce new strains that the immune system does not recognize. That’s why we tell people they need to be vaccinated annually.

A shift is an abrupt and dramatic change in a central component of the virus. It’s still the influenza virus but one significantly different from anything that we’ve experienced before.

PP: Did a shift in the influenza virus lead to the 1918 pandemic?

AF: Yes, we got a really big taste of a shift in 1918. While there were influenza outbreaks and pandemics prior to 1918, we didn’t fully recognize them until that catastrophic pandemic that killed about 50-100 million people. This was a new influenza, different from what we experienced in 1915, 1916, and 1917. And since the influenza virus wasn’t discovered until 1933, we didn’t even know it was a virus in 1918. Since its discovery, you could essentially track the influenza pandemics of 1957, 1968, and recently the swine flu pandemic in 2009.

PP: Can scientists predict if and when the next pandemic will occur?

AF: No. Some time ago, people said that pandemics “cycle,” meaning a set time when you expect a pandemic to occur. But influenza doesn’t cycle. We had a pandemic in 1918, the next one in 1957, so we thought maybe there’s a 40-year cycle, but then we had one in 1968. You really can’t predict.

PP: How effective are today’s vaccines against seasonal influenza?

AF: First, it is always better to get vaccinated than not — some protection is better than none. But having said that, the vaccine efficacy against influenza — compared to other diseases like measles — is modest. And in some years, it’s bad. In a very good year, the overall efficacy of an influenza vaccine is about 60 percent. In a bad year, efficacy ranges from 0 to 10 percent. By “bad year,” I mean a year in which the vaccine — or strains that you chose to make for the following year — was not a very good match with the actual virus that ultimately did circulate during the influenza season.

PP: After you decide which strains to put in next year’s vaccine, how long does it take to manufacture?

AF: That’s another Achilles heel in our approach to influenza. The time-honored way we manufacture the vaccine is both antiquated and inadequate. After deciding in March which flu strains to put in the vaccine for the following winter, it takes about six or more months to grow it. Historically, we make the vaccine by growing it in chicken eggs. The problem is that the longer it takes to make the vaccine, the greater the opportunity for influenza in the environment to drift. So even if you chose the right subtype or strain of virus to put into the vaccine, drift can actually give you a mismatch. And whenever you mismatch, vaccine efficacy is poor.

PP: Where are we in terms of developing a more universal influenza vaccine against multiple strains of the flu?

AF: We are cautiously optimistic that we’ll achieve the ultimate solution — a universal influenza vaccine that provides long-lasting protection against multiple subtypes of the virus. A universal vaccine will induce a response against a part of the virus that doesn’t change from season to season or with a pandemic. In other words, a part of the virus that doesn’t drift or shift.

Within the last decade or so, with advances in structural biology, we have identified parts of the influenza virus that do not change from season to season. For example, the hemagglutinin (HA) protein is an important part of influenza virus, and the head of the HA molecule mutates somewhat from year to year — and when it changes a whole lot, then we can have a pandemic. But other parts of the HA protein, like the stem, change very little. Now, we have figured out ways to selectively induce an immune response to the parts of the virus that do not change.

PP: When will the universal vaccine be ready?

AF: I can’t give a definitive time. It’s not going to happen overnight, and it will take multiple iterations of the vaccine. In about five years, we will have the first version — universal vaccine 1.0 — that will cover some major strains. In five more years, universal vaccine 2.0, that protects even more. Ultimately, we would have a vaccine with which we can vaccinate children — with maybe a booster shot every several years as we do for tetanus — that will protect them against essentially all the potential circulating strains. That is where we are right now.

PP: Where do you see flu activity this year, and how severe will it be?

AF: The 2017-18 season was the worst seasonal flu that we’ve had in the last decade, which underscores the need for getting a better vaccine. If you look at the efficacy of the vaccine this year, overall it was about 36 percent. When you look at its efficacy against the predominant circulating flu strain, known as H3N2, it was only 25 percent. These kinds of results make it clear to us that we just need to do much better when it comes to a vaccine — another reason why we’re enthusiastic about a universal flu vaccine.

PP: With the variability in vaccine efficacy, do you recommend the shot?

AF: Absolutely. Even if a vaccine is 25 or 30 percent effective, it still could prevent you from being hospitalized or dying. It may not protect you against infection, but it can certainly help mitigate the seriousness of the disease.

PP: How important are nonvaccine measures in preventing spread of the disease?

AF: It’s everything from personal hygiene to avoidance. It’s amazing how important hand-washing is because people sneeze or cough into their hands, then shake hands with you. Or they open up the door. Washing your hands really is critical. Second, when you’re in the middle of an outbreak, avoid crowded places, particularly where there are many sick people. To protect society, stay home from work when you’re sick. If your children are sick, keep them home from school. And if you’re coughing and sneezing, cover your mouth. Simple measures, but very important.

PP: Vaccines are considered one of the greatest inventions in medical history, but today there’s an increasingly vocal group of people against vaccinations — anti-vaxxers — who refuse vaccinations. What are your thoughts about these campaigns and their concerns, and what are you doing to ease fears and counter doubts?

AF: When dealing with this mindset, you have to realize that attacking anti-vaxxers will never convince them to understand the importance of vaccinations. Instead of putting them down, provide them with evidence-based information. Looking at the data, it is very clear that vaccines in general are extremely safe.

Much of the concern about adverse events associated with vaccines is based on fraudulent data and claims presented in a 1998 research study by Andrew Wakefield from England and published in Lancet — subsequently debunked — linking the MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine) to autism and other adverse events. But it’s tough to erase the report from people’s consciousness. I find that there is usually a small, hard-core group of anti-vaxxers who — no matter what the evidence says — are not going to change their minds. They feel that the risk of getting infected is so low that they don’t want to take the risk of a vaccine because there’s a considerable amount of adverse events. A significant number of people are reluctant to get vaccinated until you explain the evidence on the benefits versus the risks in a reasonable, open-minded way. The vaccine is not simply for themselves, but also the community. We have a social responsibility to get vaccinated, because we depend on everybody else getting vaccinated to protect us by herd immunity. If everybody decides not to vaccinate, you will wind up with outbreaks like the Disneyland outbreak of measles in 2015.

PP: Many young parents have not witnessed outbreaks of measles or mumps in their lifetime. Is that a factor?

AF: Yes. It’s one of those things where we are the victims of our success. There’s nothing like a good outbreak to make people want to get vaccinated. If they don’t see any disease, they say, Why do I need to get vaccinated — there’s no disease out there! The fact is that you don’t see disease because we’ve been so successful in dramatically decreasing childhood and other vaccine-preventable diseases that we tend to think, Why do we need vaccines? When there is an outbreak, you’d be surprised how people rush to get vaccinated. But when there’s nothing out there, they say, What am I worried about? There’s nothing out there.

PP: Social media wasn’t around when major outbreaks were going on. Does social media help spread this kind of misinformation?

AF: Social media is very good at spreading important information, but it is just as destructive when it’s spreading false and misleading information.

PP: Is there a central message that you’d like to share with Post readers and the public about influenza?

AF: Don’t underestimate or downplay how serious influenza can be. For some people, influenza is in reality a very serious disease that should not be taken lightly. Everyone should get vaccinated, particularly those in high-risk groups — young children, pregnant women, the elderly, and people with underlying diseases — because this is a disease you can prevent with a vaccine. While we do not as yet have a perfect vaccine, we have one that clearly helps prevent infection, and we should utilize it.

Patrick Perry is the executive editor of The Saturday Evening Post.

This article is featured in the September/October 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now