Published on November 26, 1938

I will tell you this about September. You can have it. September, I give you. While I’m giving things away, I might as well give you Sam Worthman, and if you get Sam Worthman you also get Magno Studios, thirty-one weeks of mother — at two grand a week — and a first option on me. I would like you to have Jerry Morgan, who is our agent, and if you get Jerry, you might as well have Pete Roselli, who handles the publicity. You can have the entire section of Beverly Hills bounded by Santa Monica, Sunset, Doheny and Whittier, and while I’m tossing out land grants, I might as well whip in Malibu, Brentwood, Santa Anita and Arrowhead, reading from left to right. I think you should have the Grove, the Troc, the Derbies, LaMaze and like canteens, caravanserai y posados, and as long as I’ve gone this far, I suppose I should toss in a little agenda, including the Bowl, mufflers, Snow White, lunch and the Goodyear blimp.

I give you lunch advisedly. Everything happens out here over lunch. You dabble with your sole meunière (at the Vendome on Tuesdays. Or is it Thursdays?) and Jerry Morgan sits across from you and tells you that Magno doesn’t want you any more, and that as far as Hollywood is concerned, you might just as well be back on the Orpheum circuit in 1926, following that seal act.

He doesn’t say it that way, of course (“ … don’t think you’re quite the man for the job. They want — Well, frankly, old man, they’re putting Mantino on it. Want that Coward touch. We know what we think of Mantino, so I told them that my property was no bootlicker … ”). But it is said, day after day, week after week, year after year, on Vine or on Sunset or on Wilshire, over lettuce salads and over hamburgers and over corn-beef hash and over lobster thermidor. Mantino on the job. Want that Coward touch. And you can’t give it to ’em. You haven’t got that thing. You can’t give it that umph.

That is a tangent, and I didn’t mean to get out on it. But this is my Hollywood story. Every writer writes a Hollywood story. This is not a Hollywood story to end all Hollywood stories, and it may not end even all of mine, so if I get out on a tangent again, overlook it. It’s in my hair. It dances in the lenses of the dark glasses I wear. It pinches my fingers when I put the top down on the car. It’s in the Scotch they offer me, and the rye they offer me, and the martinis-manhattans they offer me on Christmas and Easter and other religious holidays. It’s at the two-dollar windows at Santa Anita and the fifty-dollar windows at Inglewood. It’s in the spare ribs at Chasen’s and the silver furs tossed over chairs at La Conga. It’s in the air, this air that hangs here between the Tehachapis and Catalina, and it’s what makes the place run, and I give it to you.

It started on the third of September. I was having lunch with Jerry Morgan.

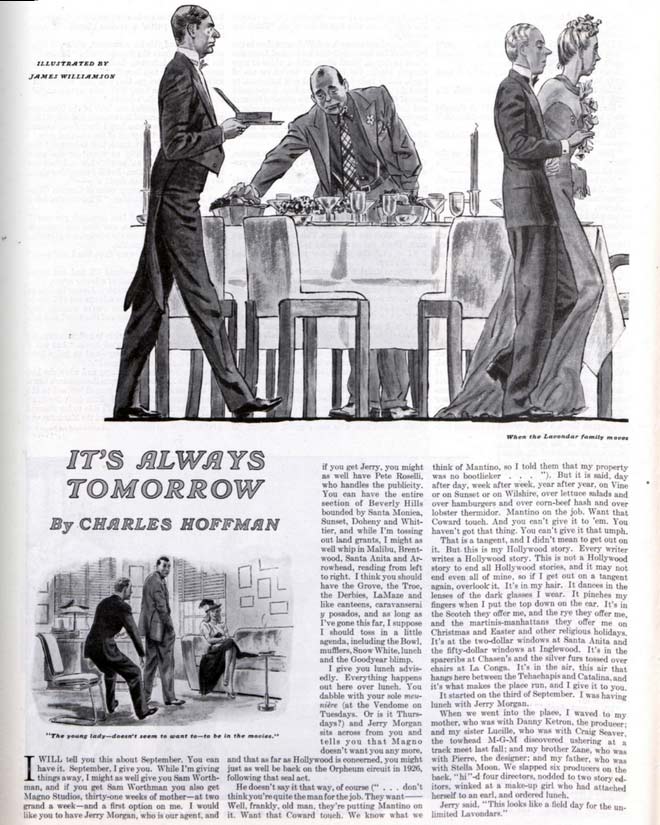

When we went into the place, I waved to my mother, who was with Danny Ketron, the producer; and my sister Lucille, who was with Craig Seaver, the towhead MGM discovered ushering at a track meet last fall; and my brother Zane, who was with Pierre, the designer; and my father, who was with Stella Moon. We slapped six producers on the back, “hi”-d four directors, nodded to two story editors, winked at a makeup girl who had attached herself to an earl, and ordered lunch.

Jerry said, “This looks like a field day for the unlimited Lavondars.”

I said, “The first family of the screen? We get around.”

“What’s your old man doing with Stella Moon?”

I said, “Maybe he’s found something, I don’t know. She’s looking for a leading man.”

Then we got to the point. “Look,” I said, “I can’t do it for five hundred, Jerry.”

“They won’t give us a cent more.”

I said, “We have a swimming pool to think of.”

“How about Lucille?”

“Six weeks at Warners’,” I said. “But that was in 1935.”

“And your brother?”

“He stood next to a horse in The Plainsman. Ten dollars a day. Both days. That paid the light bill.”

“Your father?”

“What is this?” I asked. “You ought to know. He had six weeks at Grand. They cut him out with a pair of scissors.”

“Your mother?”

I said, “Jerry. This isn’t today, this is tomorrow. It’s always tomorrow. Yesterday we ate crab Newburg in a fancy place on Sunset, which is today, and tomorrow we go out and eat ice plant, which is also today which is tomorrow. Get it?”

Jerry said, “I’ve heard of whole families getting along on four thousand a month.”

“Jerry, dear,” I said. “There’s father. There’s mother. There’s Lucille. There’s Zane. Funny thing, they eat. They wear clothes. They turn on lights, and they use water. There’s the swimming pool, and the tennis court, and four cars, and six servants, and eleven rooms, not counting the guest house. There’s a place at Malibu, and the place in the mountains. And then there’s Cousin Harriet in Omaha and her six children, and Aunt Maude in Phoenix and her little brood of five, and mother’s brother Bill in — ”

“O.K.,” said Jerry, “so what?”

“So I can’t do it for five hundred, Jerry.”

Jerry said, “This is a sick world. A sick world.”

I dropped him off at his office, and went home out Sunset in my yellow roadster. Lucille took Seaver to the studio and doubled back on Santa Monica and turned in the driveway, two minutes after me, in her long gray coupe. Dad left Stella Moon off at her apartment, and whipped out Beverly in his green phaeton. Mother had the town car, and she and Ketron went back to the studio and went over the script for Angel in Distress, while Hans, our chauffeur, stood out in the lot and smoked cigarettes at two hundred a month (not including uniforms).

“Well?” Lucille asked, as we stood in the driveway.

“No soap,” I said. “Not a cent over five hundred. How about you?”

“I sparkled until you could count carats, but it didn’t work. Mentally, Seaver’s still selling programs at the track meet. Besides, they’re going to give him Garbo.”

I said, “Who’s she?”

Father skidded in behind us. He had on a pair of my white shoes, one of Zane’s sport coats, one of mother’s mufflers, and Lucille’s beret.

“Hi, you two!”

We said, “Hi.”

“Well, Jake, yes or no?”

I said, “No. Let’s not stand out here on this big wide driveway.”

We went in.

“What’s the trouble?” father asked.

“No trouble,” I said. “I’m just not Noel Coward, that’s all. Simple.”

“Incidentally,” Lucille put in, “how about you and that Moon number?”

There was a letter on that table in the hall — the one Haines found for us at Genoa — and Lucille started to rip it open.

“Did you like it?”

I said, “Fidler will get it. That’s something.”

“That’s all,” said father.

“You mean?”

“She wants to do Peter Pan.”

I said, “If she sees fifty again, I’m Seabiscuit.”

“Anyway,” father asked, “how do you think I’d be as Wendy?”

“Guess what?” said Lucille, reading the letter.

“Go on.”

“We’re being augmented.”

“Go on,” I said.

“Cousin Harriet’s daughter, Minerva, is — ”

I said, “That’s enough. How old is she?”

“The last time anyone mentioned her, she was five.”

“When does this thing happen to us?”

“Tomorrow morning.”

“Why couldn’t I have been born with two heads,” I said, “and just spent my life in a bottle?”

“That reminds me,” said father, and disappeared.

I was lying on my stomach on a mattress on the loggia, wondering what Noel Coward had that I et cetera, when Fuzzy turned up. It was ten minutes after three, and he was ten minutes late. Usually he hits three on the dot.

“Hi-ya,” said Fuzzy, “where’s Lucille?”

I was almost afraid to look up, for fear it wouldn’t be there, but it was. The nice white letter on the nice red sweater on the broad chest. “S,” for State. Fuzzy is a letter man. He is big. He has big hands and big feet and a lot of white teeth and his hair is like cotton above his brown forehead, and he is h-e-a-l-t-h personified.

He is a D. Tau, and he knows a lot about the damndest things, like what Benny Goodman’s drummer’s hometown is, and who ran the 440 for Ohio State in 1928, and what the name of Li’l Abner’s pig is. I, myself, having been born in a trunk backstage in a New Orleans theater one sultry afternoon in 1908 (profile) didn’t get to college, and it is interesting to note from time to time what “the system” is turning out. I suppose Fuzzy is a product, and Fuzzy may also be indicative of a trend, don’t know. I do know that Fuzzy is lyrical about Lucille — which is euphonious and which I may try to sell to Sam Worthman — and also that he gets in her hair just the way Hollywood —

I said, “She’s someplace on the acreage.”

He said, “Say, d’ja hear what Marvin did?”

I turned over on my back and looked up at the bright California sun through purple glasses. “No, what did Marvin do?”

“Kicked ninety-eight yards!”

“No … ”

“Yeh! Some kick, eh?”

I said, “Boy, I’ll say.”

He said, “Well, guess I’ll go find Lucille.”

I said, “O.K.”

I took a deep breath, and closed my eyes, and started to hum I’ll Follow My Secret Heart. Take Gertrude Lawrence, take a Swiss chalet, take that line from Private Lives about the ear trumpet and the shrimps, take —

Fuzzy stayed for dinner. Remember, this is still the third of September. Mother was in one of her moods, trailing sleeves through things and talking through a lorgnette. Father was a little tight (“So I said to John Drew — Jack, I said — I always called him Jack — Jack, I said … ”). Lucille was rather pale, and quiet, and once when Fuzzy said, “You know what that guy Marvin’s got?” (I said, “No, what has that guy Marvin got?”) and he said, “Guts!” — she choked on something and had to leave the table for a minute.

The next morning, we drew straws on Minerva, and I drew the long one and had to meet her. “Look,” I said, “as long as I have a job, and you’re — well, say ‘at liberty,’ Lucille, I think you might — ” We were having breakfast. Mother had on a pink negligée and was having hot water and the Hollywood Reporter. Father had on a Chinese dressing gown and was having a sedative and Variety. Lucille had on something blue and fluffy that kept getting in her grapefruit. I had two cups of coffee and a headache (“Whenever spring breaks through again … ”).

Lucille said, “I can’t, darling. Not possibly. Larue wants me for some fittings, and — ”

“Buying clothes, dear?”

“Oh, one or two little things.”

“That’s lovely. Something for winter?”

Lucille gave me a look and went back to her grapefruit.

“If I may lapse into the pastiche,” I said, “what are we going to use for money?”

Mother said, “Jake, please!”

I looked at her. “How much longer have you to run?”

She arched. “Thirty-one weeks.”

“At two thousand a week,” father put in quickly.

I said, “That’s sixty-two thousand dollars.”

“It’s a lot of money,” said father.

“It was a lot of money,” I reminded him. “Only it’s spent. Already.”

“Well,” said Lucille, “you can’t expect me to walk down Vine Street naked!”

“No,” said mother, “you certainly can’t!”

“No,” father murmured, “of course not. Naked! Most ridiculous thing.”

I said, “OK. OK. OK.”

Just then Block S came in. “Having breakfast?”

I said, “We’re trying to preserve an illusion.”

“Say,” he said, “hear about Marvin? Pretty tough.”

I said, “What happened to Marvin?”

“Broke his toe. Last night. His kicking toe.”

Lucille looked at him, and then at me, and then at her grapefruit, and then she got up and left. And just then I got an inspiration. Fuzzy, Minerva, station. Just like that.

When I got to the studio I went into the commissary and had a cup of coffee and talked to Witherstein about a treatment he was going to do on Ladies in the Saddle. Then I went up to my office and told Pearl she could go have a cup of coffee, and sat and listened to that buzzing sound you hear up there, and finally went down to Foster’s office and talked about a treatment he was going to do on Mrs. Manners Runs Wild, and went and had a cup of coffee. About one o’clock, Jerry came in and we went over and had a cup of coffee, and at one-thirty I walked into the Vine Street Derby, and was worn out.

I waved to mother, who was with Toby Forrester, and to Lucille, who was with someone quite short and without any neck, and to father, who was with Eva O’Neil (remember Eva?), and to my brother Zane, who was with Pierre, the designer. I slapped six producers, and so forth, and ordered coffee and a telephone, and relaxed.

Sam Worthman had “planed out,” and the studio was tout court, so I went home about three o’clock and spread out on my stomach on a mattress on the loggia. I suppose I had been there about half an hour, when this thing floated before my vision.

I looked up. It had long yellow hair — not Westmore yellow; more on the sun-on-cornfields side — and a very red mouth and a little parade of freckles across something that should have been a nose, and it had on a bright green sunsuit and little green sandals.

“Hello,” I said.

It sat down on the hammock next to the mattress and took a white cigarette case out of the big beach bag it carried. “Smoke?”

I said, “No, thanks. I don’t drink either. I’m Jake.”

“I’m Jake, too, thanks,” it said.

I sat up and pulled my knees up under my arms and said, “Been here long?”

“If you mean do I know my way around, yes.”

Things were happening around us. Cotton clouds floated across the sun for a minute. Something chirped in a tree. Block S darted out of nowhere and slithered into the pool like a seal in white trunks.

I said, “I take it for granted you’re Minerva.”

“Do tell!” it said.

I turned over and spread out on my stomach again, and pretty soon Block S heaved himself out of the pool and came over and dripped on my legs.

“Well,” he said, “I got her, all right, all right.”

I said, “You sure did,” into the crook in my elbow.

I don’t know what would have happened then, if Lucille hadn’t come in. I mean, we might have reached an impasse.

“I’m Lucille,” Lucille said. “I suppose you’re Minerva.”

“I’m Minerva, all right,” said Minerva, “but I thought you’d be so much younger.”

Block S said, “Come on, honey. Two laps,” and Minerva jumped up, and with one swift movement took off her sandals and her glasses, put out her cigarette, pulled on her cap, and was across me in a leap and into the pool.

“Two lapse,” I said.

“Insidious little thing, isn’t she?” said Lucille.

I said, “Particularly for a girl of five.”

Block S stayed for dinner. Jerry Morgan was there (if he doesn’t get his ten percent that way, he gets it another), and the President of the Lavondar Family (“The First Family of the Screen”) Fan Club of Terre Haute — in purple chiffon and a daze, who had won a trip to Hollywood collecting soap coupons — was there. Lucille was there, and Minerva was there in something flowered.

Mother did a Bernhardt, and knocked over a glass of champagne (Salinas, 1938) and father got — shall we say “mellow”? — and Block S demonstrated, with a hard roll, how Marvin broke his toe (“Crunch,” said Block S, “like that”). The P. of the L.F.F.C. of Terre Haute had the jitters, and the only time Minerva opened her mouth was when I said, “Did you have a good trip out?” and she said, “There wasn’t a man under sixty on the whole train.”

On our way out of the dining room — when the Lavondar family moves in a group, the only thing missing is a calliope — mother touched my arm.

“Who is the one in that print?”

I said, “The one in that print is what we drew straws for at breakfast.”

“What was her name again?”

I said, “Her name is Minerva, again. You remember, Cousin Harriet’s error?”

“What’s she doing here?” mother asked.

I said, “She’s visiting.”

“Who?”

“Us.”

“Well I must speak to her.”

I should have known what was going to happen the next morning. I should never have gotten up or, better still, I should have gotten up early and gone out to Santa Monica and walked into the ocean and just kept walking. Then I would have washed up on Marion Davies’ stoop, and The First Family of the Screen would have had one out on second. But oh, no, there was little Jake at the breakfast table, and sure enough, just when I was finishing my coffee, in comes Minerva in mufti.

She said, “Well, I’m ready.”

Mother said, “Father, this is Minerva. Minerva dear, this is father.”

Minerva said, “Whose?”

She had on a blue dress and it was just exactly the color of her eyes. And she had on a blue hat, from which the tail feathers of a Nebraska rooster waved gaily in a morning breeze in California. And she had on white shoes and carried a white bag, and if she looked five, they dug me up someplace in Egypt. (Jake Ankh Ahman.)

I said, “Where you off to?”

“Oh,” she said, “I’m ready to see Hollywood.”

Lucille tried to vanish, but I caught her by one sleeve. “What are you doing today, darling?”

“I’m dreadfully sorry,” said Lucille, “I’m absolutely heartbroken, but — ”

“Skip it,” said Minerva.

“Mother?”

“Yes, Jake?”

“Mother, Minerva — ”

“Oh, yes. Minerva.”

“Mother, could you — ”

“I’m so sorry,” said mother, “but we’re going on location today. To Omsk.”

“Father?”

“Uh?”

“Father, Minerva — ”

“That’s all right. Just run along, Minerva. That’s quite all right.”

Minerva looked at me. I said, finally, “O.K. Come on with me, and we’ll run off Birth of a Nation for you.”

When we got to the office, I said, “Pearl, this is Minerva. Minerva has never been on a lot before. In fact, Minerva has never been to Hollywood before.”

Pearl said, “I get it. So what?”

“So take her out and show her what makes it tick.”

I was reading the Racing Form when Pearl came back and came in and sat up on my desk.

“Look,” she said, “I’ve been around Hollywood 29 years and did anyone ever notice me?”

I said, “Bring it out in the open, and I’ll run it down.”

“Did Lou Sardin ever look at me?”

Lou Sardin is the main producer on our lot.

I said, “I don’t know. Did he?”

Pearl got down off the desk and snorted, “No! But just let some Omaha houri — ”

You know that way light comes through. You know that way it falls in a shaft to the floor, with little things dancing in it. Little things began to dance in me. Dawn broke.

I said, “Oh, so that’s it, is it?”

She said, “Did you ever hear of Cinderella?”

And I said, “I wrote it,” and dashed out.

“Look, dear,” I said to Sardin’s secretary. “I have to see Sardin. It’s a matter of life and death. It’s worse than that. It’s vital.”

She said, “Mr. Sardin’s out. He’s at Malibu. He’s in the East. Far East. China. He’s in conference.”

“Honey,” I said, “I’ve been here too long for that one. There hasn’t been a conference on this lot since Booth shot Lincoln.”

“Didn’t see it,” she said. “Who was in it?”

“Look,” I said. I put my hand down on the desk with the palm up — you know — I ran the other hand through my hair. “I have to see Sardin. It is quite important. It is important to me and it is important to the studio and it is important to Mr. Sardin. I found gold on Stage C. I hit oil in my inkwell. Shirley Temple — ”

“You,” she said, “are getting purple in the face.”

Just then Sardin opened the door of his private office and saw me. “Lavondar!” he called. “Just the man I wanted to see! Come in! Come in, Jake, old man!”

“Bah!” I said to his secretary, and went into the square modern room, and there was Minerva.

“Oh, hello.”

“What do you mean,” said Sardin, “by letting Miss — Miss — this young lady wander around alone on the lot?”

I said, “I’m sorry. I couldn’t help it. It’s like keeping chipmunks. It’s like keeping some of those little lizards that — ”

He said, “Jake, this is a valuable piece of property. I’m trying to get her to sign up with us.”

I sat down, and luckily there was a chair there. Minerva lit a cigarette and smiled sweetly at me and adjusted things on her shoulders.

I said, “That’s — that’s — ”

He said, “I wish you’d bring a little pressure to bear. You see, she — ”

I said, “I’m sure that won’t be necessary.”

“Oh, but it is,” said Sardin. “The young lady — doesn’t seem to want to — to be in the movies. Shall I put it that way?”

Minerva said, “That way’s as good as any.”

I said, “What?”

Minerva said, “I’m sorry. I — I really don’t want to be in the movies.”

He said, “I can get you a grand a week. On this lot. I — ”

One thousand a week. Forty-two weeks a year. And it wasn’t spent. We already had a swimming pool. We already had the place at Malibu. Forty-two thousand a year. No ten percent. No nothing. Just the money, the rhino, the mopus, the dibs.

“Honey — ” I began.

Minerva said, “On Wednesdays, where’s the place to eat lunch?”

I don’t know what it was, I’ll be damned if I do. Maybe it was something someone sprinkled on us. Maybe a wand waved, off there. Maybe it was just the rooster feathers. But this time there was no slapping producers on the back. Producers were slapping me. On the back. Me. Jake Lavondar. I give it to you.

We drove out Sunset to the beach. “Minerva — ” I started, someplace along the way. I made a picture of it you could have hung in the Louvre. I brought all of them out here — those blondes from Jersey, those brunettes from the cotton states, those redheads from the Rockies. I walked them until there were holes in the soles of their shoes, up Vine, down Gower, out Santa Monica, and then I spread them out in a thin layer over town — hash houses, bars, drive-ins, restaurants, beauty shops, theater exits, glove counters. I gave it glamour, I gave it romance, I gave it heartache. I went into statistics.

Someplace, I stopped the car and said, “Minerva, I don’t do this for everyone. But — ”

“What does he do?”

“Sardin? He’s one of the biggest shots — ”

She got a look, just kind of a simple soft little look. “No, not him.”

I said, “Milt Grosman?” (Milt had wandered in on us at lunch.) “Milt’s one of the hottest — ”

“No,” said Minerva. “Not him.” Now impatience shadowed her words. “That one who’s around your house so much. The one with the letter.”

“Oh?” I said — the road ahead of me rolled dizzily. I whipped my window down and put my head out and breathed in some cold air. “Him?”

“He’s awfully cute,” said Minerva.

When we got back to the house, Block S, The Constant, took over — Minerva said, “Hello, stupid”; I said, “She’s yours, you can have her, I give her to you”; he said, “Thank you, sir. Come on, gorgeous” — and I went out by the pool. I had been thinking. I was older then.

Pretty soon, Lucille wandered in.

“Home early.”

I said, “That’s right.”

“Nothing doing at the studio?”

“That’s right.”

She sank down on the hammock beside me. She took off her little felt hat and ran her hands through her hair, and leaned back, closing her eyes.

“You know,” she said, “sometimes it isn’t funny out here.”

I said, “That’s right.”

Pretty soon she opened her eyes and just looked up at the top of the hammock, and her lower jaw came out and the white teeth in it sort of bit her scarlet upper lip.

“I’m tired out, Jake. I worked on Lenny Deveaux for three hours and forty-seven minutes for a part in Sing to the Sky, but — ”

I said, “I know. It’s lousy.”

“It’s Gehenna.”

“It’s Sheol.”

“It’s Purgatory.”

“It’s Limbo”

“It’s — oh, nuts!”

I said, “Magno wants Minerva at a grand a week.” I said it just like that. I kept my voice on a nice even plane, and I tried to make the words sound pleasant. A hummingbird, of all things, danced along the box hedge beyond the lawn. A swallow tipped the pool in flight. “You remember Minerva.”

“You mean — ”

I said, “Life is a black widow spider. Under the wood in the garage.”

“And?”

“And she said thanks, but she didn’t want any. She wasn’t interested in pictures. A thousand a week was so much corn meal.”

“You,” said Lucille, standing up and looking at me, “must think I’m an awful fool.” She turned and walked into the house, and I shrugged my shoulders and sat there and grinned, bansheely, at the hummingbird. They found me there, hours later.

The next morning I got up at five o’clock, and went out and drove around until it was time to go to the studio. That way, I avoided taking Minerva with me.

Mother got caught. In a way, it was really terrific. I saw them at lunch — Minerva and mother and A.E. Andrews, the producer at Goliath Studios. A.E. was talking to Minerva, and mother was just sitting there. When I went in, I waved to her, and she gave me kind of a sick little smile. You could tell that A.E. was being very positive about something — as it happened, he was offering Minerva one-fifty a week on a five-year contract and to hell with the New York office — and Minerva was all sort of sweet and cool and dumb, in pink.

They passed me, on the way out.

A.E. said, “Try and pump some sense into this girl, Jake.”

Minerva said, “Oh, Jake, could Fuzzy and I borrow your car this afternoon?”

Mother said, “The moving picture is a peculiar form of art.”

I said, “I am reserving a suite for us at Patton.”

That afternoon I went around to see Jerry. At Magno, I was coming to an end.

“Jake! Just the man I wanted to see!”

I said, “That’s fine. Got something red-hot for me?” That fear that had been gnawing down there, stopped gnawing and sat still for a minute.

“You’ve got something for me,” Jerry said. “Who is this gal Minerva?”

“Oh. Her.” Fear started feeding again. “A cousin from Omaha. Why?”

“The whole town’s after her. Warners’ called. Said they’d heard you knew her. They’ll give us a thousand a — ”

I said, “I know. Jerry, look. Tomorrow is my last day at Magno. I’ll take that five hundred — ”

He said, “Where is she? Why isn’t she here? Why didn’t you bring — ”

“I’ll take that five hundred, Jerry. I’ll come down. I’ll be a good guy.”

Jerry said, “Man, let’s get that dame signed up! That’s a gold mine!”

“Jerry,” I said gently, “it’s no go.”

“Wattdyamean ‘no go’? It’s a sensation! We’ll spread her name from — ”

“Jerry, dear. She doesn’t want to be in pictures.”

“She what?”

“She doesn’t want to be in pictures.”

“Don’t be a fool, Jake. There isn’t a woman in the United States who wouldn’t — ”

I said, “Minerva wouldn’t. I know. Life is a black widow spider. Under your shoes in the closet.”

Jerry said, “Jake, old man, you wouldn’t do this thing to me.”

I said, “I’m sorry. I don’t like it. But it’s the truth. She’s blond. She has blue eyes. She has a neat little figure. And she doesn’t want to be in pictures.”

Jerry sat there shaking his head like one of those little papier-mache dragons you can buy in Chinatown.

“But, Jerry,” I said. “Take me. Now, I am absolutely aching to be — ”

He drew into a shell. “Sorry, Jake. They filled that job.”

“You mean — ?”

“If Shakespeare walked in here now, I couldn’t get him a job. Depression. Recession.”

I said, “Who’s he?” But it wasn’t funny. Fear finished the first course, and went into the entree.

The telegram reached our house the next morning about ten. I was at the studio, cleaning out my desk. People were coming in and saying goodbye and then going over to the commissary. The good old commissary!

Millie, our second girl, read it to me over the phone. I might have known — when they didn’t come back, Fuzzy and Minerva, and when my car didn’t come back. Anyway, it was from Nevada, and it wasn’t a very clever telegram, but somehow you could see those two youngsters standing there at the counter and writing it out, sort of giggling and sort of clean and sort of American. With a capital A. Life goes to a party.

I said, “Thank you, Millie,” and hung up, and told Pearl to get Lucille on the phone, for me. Lucille was in a beauty shop in Westwood.

I said, “You’re back in circulation again.”

She said, “Go on. I’m having a shampoo.”

I said, “Minerva and Fuzzy were married in Reno this morning. Tum, tum, te-ump, tum tum tum.”

For a minute, she didn’t answer. Then she said, “I was going to marry him.” It wasn’t bathos. It was sort of a little complaint. Her voice sounded as if she had soap in her eyes.

I said, “I don’t know what to say to that. I can’t think of any bright cracks.”

She said, “Well, to a certain extent it thins out Hollywood.”

I said, “OK, heartbroken, go back to your basin,” and hung up.

Pearl came in, and I said, “Remember Minerva?”

“At night I wake up and hate her,” said Pearl. “You want your typing paper?”

I said, “Well, you don’t need to hate her any more. She’s married. Yes, I want my typing paper.”

“Look,” said Pearl, “I’ve been in Hollywood twenty-nine years, and am I married?”

I said, “I don’t know, are you?”

“No,” said Pearl.

The line formed at the left, and I paid off. Two hundred to Epstein for that bet on Farr. One-fifty to Movet for that loan in August. Six hundred to Jimmy Nebeker for that night at the Clover Club. Eventually, the office was empty, and I stood there and looked down at the lot through the Venetian blinds, and I felt very bad. Even that buzzing noise was lovable. Pearl came in and wiped tears away and said it had been fun to work with me, and I borrowed three dollars from her for lunch. You have to keep up appearances.

When I got there, I fixed my tie in the car and smoothed down my hair and adjusted my coat. “This is tomorrow,” I said to myself in the rear-view mirror — which was kind of symbolical — and went in. I sat down alone at a table next to the wall and looked at the menu, but I wasn’t very hungry. After the waiter had taken my order, I folded my hands on the cloth and looked around.

Mother was sitting in a corner with someone I didn’t recognize, and father was at one of the center tables with a woman who looked a little bit like Equipoise. Lucille wasn’t there yet, but my brother Zane was there, with Pierre, the designer. When I caught his eye, I waved to him. That ties the story together.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now