As a writing team, Edwin Balmer and William MacHarg collaborated on several detective stories in the early century, notably The Indian Drum and The Achievements of Luther Trant. In the years between the keystone mystery fiction of Poe and Christie, Balmer and MacHarg’s works filled the genre’s gap with clever and thrilling tales tinged with science and romance.

Published on June 26, 1926

An incident, trivial in itself but not at all trivial in its possible consequences, occurred at the Montview Hotel, Denver, during the first week of July. It so aroused the curiosity of Goebel, the resident manager, that he referred it to Steve Faraday, owner of the Montview and half a dozen other Faraday hotels, when Steve made his regular visit a few days later on his midsummer swing of inspection.

“Our register for March 15th, three years ago, has suddenly become mighty important to somebody,” Goebel reported.

“How important?” asked Steve.

“This is all I know now: Last week — Monday, it was — a good-looking, very attractive young fellow — English-looking and speaking like an Englishman — came in when I happened to be in the front office. He asked for our register for March, three years back; said he was an attorney for a party in a lawsuit and wanted to prove by our records that a Franklin Smith was in New York, and not in Denver, on March 13th. I sent to the file room and let him look at the register.”

“All right,” said Steve attentively.

“He appeared all right,” Goebel continued. “So I did not watch him. He looked over the book for a few minutes and turned it back to me, thanking me very politely. I remember I asked him, ‘Was your man here?’

“‘He wasn’t. That’s what I wanted to show,’ he said. Then he went out; and no one here saw him again; but on Wednesday night the book was taken.”

“How taken?”

“It was stolen from the file room. The clerk in charge reported to me a volume missing. It was that book for March, three years back.”

“You had returned it to the file room?”

“Yes.”

“Nobody on the staff had taken it out again?” asked Steve. The loss of a register, three years old, would not have impressed him as important except for Goebel’s evident interest. Steve considered, however, that Goebel, though an excellent manager, was likely to exaggerate small incidents.

“No; nobody of the staff had it out,” replied Goebel positively. “The file-room clerk is sure it was taken outside the house. Naturally, I thought of the Englishman who’d asked for it Monday. It looked to me that, being interested in a lawsuit, he’d wanted some record destroyed. But the next night the book was back.”

“Who returned it?”

“We don’t know. There it was in its place again.”

“With all its pages?”

“Yes; nothing torn out.”

“What was done to it then?”

“I looked first on the pages for March thirteenth. My idea was that he’d taken it to change some entry about his Franklin Smith. There was no Smith on the pages for the thirteenth; but on the fifteenth was this”:

Goebel opened the big book, bulky in its permanent binding, and Steve ran his eye down the list of names in the different individual hands of the guests of three years and four months ago:

A.G. Sprague and wife … Pueblo.

H.E. Henty … St. Louis, Mo.

Arlo Kane, Mrs. Kane and maid … N.Y. City.

L.B. Hougham-Stearns and son and manservant … London.

“Fourth line,” Goebel directed, and he held for Steve a magnifying glass. “Now look at it.”

“Name looks all right.”

“But after it ‘and son and manservant.’ Isn’t the ‘and son’ crowded and the ink in those two words newer?”

“You mean you think this has been changed since the original entry, which was ‘L.B. Hougham-Stearns and’ — ”

“ — ‘and manservant,’“ said Goebel. “But originally I think there was a little blank space left between the name and ‘and manservant’; and somebody recently wrote in ‘and son.’ I’ve looked through the rest of the book since I saw that. There are other crowded entries and several erasures; they plainly were made in the regular course of business; but this one, I’m sure, is fresh.”

“What do you make of it?” asked Steve, still doubtful whether the entry had been changed.

“I make it mighty important for somebody to want to be able to prove that the son of L. B. Hougham-Stearns, of London, was here with him three years ago last March as well as the manservant. So he, or someone else for him, came in and had a look at the entry, saw how it might be changed, got the book, made the change and returned it to our possession so that he can prove by it, later, whatever it’s important to him to prove.”

“H’m — who’s L.B. Hougham-Stearns, of London?”

“I don’t remember him at all; but you can see from the register he had our best suite; and day before yesterday this was in a newspaper.” Goebel handed Steve a clipping from a Los Angeles newspaper and Steve read:

“Sussex House in Southern California, the home of L.B. Hougham-Stearns, who came to California from London about three years ago, is reported to be for sale. Mr. Hougham-Stearns came to California because of conditions of health and was so improved that he decided to settle and he made immense land purchases. Recently, his health has again failed; and though he finds California most delightful, sentimental ties recall him to England.”

“H’m!” said Steve, considering. If the entry in the register really had been changed, the appearance of such an item at this time suggested a design of importance. On the other hand, Steve wondered whether Goebel had been so certain that there had been a change in the entry after Hougham-Stearns’ name before he had discovered the newspaper item.

“What’d we better do?” asked Goebel.

“Nothing,” said Steve, “except keep this to ourselves. If this entry has been changed and the book is wanted, we’ll hear from it. By the way, did you by any chance take any action which would have informed the thief — I mean the borrower of the book — that you missed it?”

“No.”

“That’s good,” said Steve. “Then whatever’s coming — if anything does come — is sure to come to us.”

Steve Faraday, who was twenty-six, had, you see, inherited his hotels. They had come to him from his father as going concerns, financially successful and with a perfected organization; so upon Steve had devolved their development along their newest and, to him, most interesting phase — the ministering to the tastes, individual needs and even fancies of his guests.

Sooner or later, Steve knew, nearly everybody in the civilized world stops at a hotel, and often at the most critical period of their lives. Steve found the strange, unexpected and unpredictable events constantly occurring among the ten thousand persons who nightly sought the shelter of his roofs the most fascinating feature of his business; and to the precepts left by his father to the organization, and repeated and quoted, he had added another of his own invention which he thought particularly applicable to such cases: “Service which exceeds the guest’s expectation is the most efficient, although silent, advertising.”

At his hotel in St. Louis, where he had been four days before his arrival in Denver, for instance, a guest — a woman — had attempted suicide. Revived and restored to herself in the hotel hospital, she had refused to give any reason for her act or any particulars about herself. The incident made a five-line paragraph in the newspapers. It had not become known outside the hotel that the initials on her hand baggage corresponded, not with the name she had signed upon the register, but with those of one of the characters in a famous divorce case.

On leaving Denver, Steve went to Chicago, where, at his house, the Tonty, the problem of procedure momentarily concerning the management was the question whether a huge black-bearded man who had registered as D. Cozene, of Belgrade, and who spoke no English, had liberty of movement or was in fact practically imprisoned in his room by the intimidation of his two attendants. This doubt Cozene himself cleared up, the day after Steve’s arrival, by going out alone. And leaving for Cleveland on the second evening later, Steve’s thoughts turned to his Cleveland house, the Commodore Perry, and to the counterfeit money which had caused its management so much annoyance.

Bills of twenty-dollar denomination, so excellently made as to make detection difficult, had appeared in circulation in the hotel just previous to Steve’s stopping there on his way west some two weeks previous. Numbers of them had appeared in the receipts of the various cashiers; some had been refused in the hotel’s deposit at the bank; and, what was more serious, many of them had found their way from the cashiers into the possession of guests. The money loss to the hotel had been only a few hundred dollars; the annoyance to his guests Steve could not regard so philosophically. Not less than a dozen letters had been received from departed guests, inclosing one or more of the bills which they had received in change at the hotel. Steve readily could put himself in the place of one who, leaving the hotel with perhaps eighty dollars in his pocket, found half of it bad. Then the bills had stopped.

Steve had left it to Claflin, his manager at the Commodore Perry, to determine their source and whether a guest or a member of the staff had put them in circulation; now he remembered that he had heard nothing from Claflin in regard to it.

Arriving at the Commodore Perry in the morning, Steve greeted his manager in the front office.

“Send Ebor a dollar,” Steve directed one of the clerks on duty. Ebor was the taxi starter. “He paid for my cab.”

Claflin drew him aside quietly. “Have you a big bill on you?” he asked in a low tone. “Fifty or a hundred? Change it yourself then at the front cashier’s window.”

Steve looked at him quickly. “You mean it has begun again?”

“Since yesterday.”

“The same bills as before?”

“Yes; twenties.”

“And you suspect one of the staff?”

“It looks like it.”

Steve moved to the front cashier’s window with curiosity as to whom he would find on duty.

“Why, Mr. Faraday!” a girl’s pleasant voice greeted him from behind the grating; and Steve faced, to his surprise, not a stranger, as he expected, but a girl well and most favorably known to him.

“How do you do, Clara?” he asked, reaching under the grating to shake hands with her. His feeling chiefly was irritation at Claflin, who, if he suspected this girl, must have made a mistake. She was a very good-looking girl, with large brown eyes, brown hair and a pretty skin; intelligent and with a nice manner. She was Steve’s own age and he had known her since she was sixteen, when she was a check girl in Chicago. Since then she had worked up to her present position as front office cashier.

Instinctively Steve recoiled from the test of her; but he went through with it, and after a few words he handed in a hundred-dollar bill.

“I need a dollar, please,” he said. He noticed, as she counted out the money, a small diamond on her left hand; then she returned him four twenties, a ten, a five and five ones.

Claflin led him thereupon into the private office, where two strangers — a shrewd-looking man of twenty-four and a portly gray-hair — were sitting. The young man arose, but the older one sat estimating Steve with his even gray eyes.

Steve had not yet put away his money. “You just got that at the front cashier’s window?” the gray-hair asked, after the door was closed.

“Yes.”

“Keep it separate.”

“Mr. Faraday, this is Captain Norton, of the United States Secret Service,” Claflin somewhat nervously introduced the gray-hair. “Mr. Ashlander is on this case with him. They both know who you are.”

Steve pocketed his money. “I’ve heard of you often, of course,” he said to Norton. His irritation against Claflin was increasing, as his mind went back for the moment to the brown eyes and pleasant appearance of the girl in the cashier’s cage. “You asked the Government in on this matter then, Claflin?”

“No.” Claflin was a wiry, uneasy, spectacled man of forty. “No,” he repeated; “they came here of themselves this morning.”

“The cashier of the Guardian Trust, your bank, reported to us a number of counterfeits in your deposits of last night, which the bank refused,” Ashlander explained easily. “The same thing, according to him, occurred in larger number between two and three weeks ago.”

“Yes,” Steve admitted. He was not actually resenting the appearance of the government men in the case; his hotels, to be sure, usually handled their problems for themselves and called for outside help only after they knew what action would be necessary. It was their mistake regarding the front office cashier that he resented.

“Captain Norton and I came over this morning and did a little work,” Ashlander continued; and Claflin drew open a drawer of his desk and extracted a little packet of new bank notes which he spread out on the table before Norton and Ashlander.

“Twenty-dollar Federal Reserve notes on the Federal Reserve Bank of New York; check letter A, plate number 121; Carter Glass, Secretary of the Treasury; John Burke, Treasurer of the United States; portrait of Cleveland,” Ashlander announced quietly.

“Counterfeits?” asked Steve, fingering one.

“Very good ones; excellent; unusually deceptive, and they all came out of your front office cashier’s cage this morning.”

“They’re the same, are they, as those you took up before?” Steve asked of Claflin; but it was Ashlander who answered him.

“Off the same plate, Mr. Faraday. We’ve examined the other ones. They’re from an engraved steel plate made by an expert, with very minor errors. The faults in the portrait of Cleveland are a slight narrowing of the chin and in the line of the temples. Compared with a government note of that series, you can scarcely see the difference; it’s almost microscopic.

“The seal and numbering also are very good; and the bills have been numbered serially. The paper is not quite so good. It is too stiff and brittle and the silk fiber is bunched more than in government paper. But it’s an extraordinarily good counterfeit. Only an expert could detect it.”

Steve glanced at Claflin; he drew from his pocket the crisp bank notes handed him a few minutes before by the brown-eyed girl at the cashier’s window of the front office. He sorted out the four twenties and compared them; then shook his head.

“What are mine?” He referred to Ashlander and laid the bills before him.

Ashlander bent and examined them carefully. “She gave the boss a fifty-fifty break, Mr. Claflin,” he reported to the manager. “These two are government engravings; these two are off that plate.” He gestured to the row of counterfeits.

“I know that girl.” Steve impulsively rallied to his cashier’s defense. “I’ve known her since I was in school. You’re accusing her of what, exactly?” he demanded of Ashlander, who glanced at Norton.

“We have traced, definitely, I should say,” observed the captain dryly, “this bad money to her hands. We are not saying that she is the source of supply of it; but she certainly seems in touch with it.”

“What does she say about it?”

“Say?” repeated Ashlander, smiling. “We haven’t put it to her personally yet. She’d be a cool one to shove you two queer notes out of four if she knew we were watching her.”

“She knows it was suspected before,” said Steve.

“But she was not suspected then, Mr. Faraday,” rejoined Norton. “We’re not accusing her yet. This case has certain extraordinary points of its own. Tell me what you know of the girl.”

“Where’s her card?” Steve asked Claflin.

“Of course I’ve seen her employment record,” said Norton, and referred to his notebook, reading: “‘First employed as coat-room girl in Hotel Tonty, Chicago, 1916; transferred to rear office; typist; assistant accountant. Sent to Denver, Montview, August, 1922; assistant cashier; May, 1923, transferred to Commodore Perry, Cleveland; cashier.’”

“Her record has been good; in fact excellent. Her family consists of her mother, whom she supports.” He closed his little book. “What can you add to that?”

“You must be able to read between the lines of her card,” Steve replied warmly. “From the time she was sixteen she’s supported herself and her mother. She went to night school. She’s kept herself bright, cheerful and attractive. She’s just the kind of girl we like to have. She makes it a pleasure to deal with her, and Claflin may have told you that we’ve been grooming her for even a better position, in the chief accountant’s office, where she would handle all the money that comes into this hotel. That’s what we think of her.”

“You know, I suppose,” asked Norton calmly, “that she’s got engaged recently?”

“No,” said Steve, but remembered the small diamond he had seen on her finger. “What’s that got to do with it?”

“Anyone who deals with women learns that a woman of herself and a woman in love may be two entirely different individuals. A girl, especially of a fond and affectionate nature, will do for a man she loves what she never would dream of doing for herself. We’re ready to talk to your girl.”

“Bring her in here,” Steve said to Claflin.

“Have her bring her bank with her,” warned Norton. “Don’t turn it over to her relief.”

“She wouldn’t do that in any case,” said Steve. “Each of our cashiers has a separate cash box, with a bank sufficient to handle the business of the watch. On going off duty the girl puts all vouchers, checks, receipts and money in an envelope which she turns over to the accounting department. When she goes on watch she has her own bank again.”

“Better send for her relief,” suggested Norton. “She’s not likely to go on watch again this morning.”

Steve waited with a warmth of confidence in his cashier which increased as she appeared with Claflin, the large brown envelope of her bank under her arm.

She was of good height and slender, with a straight frank bearing and a pleasant friendly manner of meeting one with her lovely soft eyes. As Claflin made the introductions she repeated Norton’s and Ashlander’s names, puzzled a little, but not obviously frightened. She glanced questioningly at Steve, who tried to smile reassuringly. She laid the large envelope of her bank upon the table.

“We’re of the Federal Secret Service,” Norton told her, “here on the business of counterfeit twenty-dollar bank notes which have been circulated in this hotel.”

“Yes?” she said, still unfrightened.

“We’ve been watching your window this morning.”

“Mine?” she repeated, and looked at Steve.

“What do you know about it, Clara?” he asked her.

“Know?”

“I mean, have you been aware that you were passing counterfeit money?”

“Was I doing that?” she asked, so unafraid and frankly that Steve clung to his confidence in her, though he said, “You gave two to me in my change.”

“Did I?”

“You did not know it?” Norton challenged her direct.

She flushed, but met his eyes. “Of course I did not know it. Why — why — ” She stopped.

“You’d better open her bank,” said Norton to Steve, who handed her the envelope.

“You open it, Clara,” he said.

She took up her envelope in her slender pretty hands, which quivered slightly as she broke the seal and spread the money, checks and vouchers upon the table. Ashlander sorted over the bank notes, taking out the twenties.

“She’s passed on all the bad ones,” he reported to Norton; and opening the drawer of the desk he took out the two bills which, half an hour earlier, she had given in change to Steve.

“You recognize these, Miss Ingram?” he asked her.

“No.”

“You handed them to Mr. Faraday. They’re counterfeits.”

“I did not know it.”

“They could not have been in your bank, Clara,” said Steve, “when you got it from the accountant’s office this morning. They’ve come in since. You’d been warned against bills of this denomination and issue. Do you remember from whom you got them?”

“No,” she said; but now her frankness was gone. She seemed to catch herself together. She raised her eyes and threw back her head with a gesture, not of fearlessness but of defiance, which struck from Steve his confidence.

“We’d better go on with this,” observed Norton watchfully, “after we’ve searched her room. You will go with us and accede to a search?” he asked her. “Or shall we make the formal preliminaries?”

“I’ll go with you,” she said.

“I’ll go along,” Steve offered, trying to recover his confidence in her.

“Do,” urged Norton. “Take her with you. I’d prefer to have you go out with her as though on some ordinary errand. We’ll meet you at her rooms.”

“Get your hat, Clara,” said Steve. “Mr. Claflin will turn in your bank.”

During the minute he waited for her Steve hoped that upon her reappearance his faith in her would increase; the contrary occurred. She was very trim and neat-looking in her small hat, but more nervous than before and bearing herself more definitely with defiance. Steve, without speaking, accompanied her to the curb.

“Yes, cab,” he said to Ebor.

“It’s only a few blocks; I nearly always walk.”

“We’ll ride,” said Steve, and put her into the cab ahead of him.

She sat uneasily beside him, glancing out her window.

“You’ve become engaged recently, I hear,” he said, after he had asked and received from her the street number and had passed it to the driver. She was so intent at her window that he repeated his comment with something of a challenge before she replied, “Yes, I’m engaged.”

“To one of our people?” questioned Steve.

“What?”

“To one of our people?”

“No, he’s not on the staff.”

“Who is he?” Steve persisted.

“I met him when he was staying at the Commodore Perry,” the girl replied, half turning to Steve and, it seemed to him, softening somewhat from her defiance. “He is Mr. Howard Jentnor.”

“I don’t know him,” said Steve.

“He is a very nice man.”

“What line is he in?”

“Insurance.”

“What company?”

“No special company,” she replied more stiffly. “He’s a broker.”

“He’s at our house now?”

“No, he moved about a week ago, after we became engaged. We want to save money now, you see,” she said, and seemed to realize how this increased the suspicion against her. “What are they looking for in my rooms?”

“I don’t know.” And talk between them lapsed.

He helped her out before an old but well-maintained building of large apartments, originally, which now were cut into little ones of one or two rooms apiece. Clara Ingram opened the entrance door with a key, and when she came upon Captain Norton and Ashlander in the entry she started, but said only, “I hope mother’s out.”

“No one is in your apartment,” Ashlander assured her, and with her latchkey she opened the inner door.

“We are going to be thorough,” Norton warned her, “so if you are hiding anything you had better give it to us at once.”

“I could give you nothing but my clothing and mother’s, and a few old keepsakes and letters,” she replied, so honestly that Steve was stirred again to believe in her; but Ashlander opened her dresser drawers, lifting and shaking out filmy folds of silky things. He examined a handkerchief box and undid a package of gloves. Nothing extraordinary rewarded him.

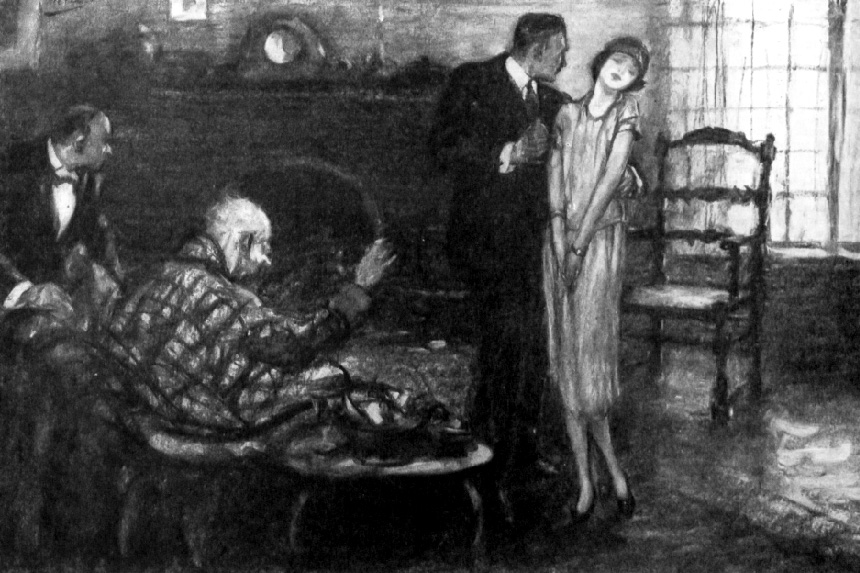

Norton attacked the closet wherein dresses and skirts were hung, and hats and boxes stood on an upper shelf. He brought down the boxes, searching them without objection and without result until he opened a pasteboard carton packed to the top with bundles of letters, tied with faded ribbons or neatly knotted string. For the first time Clara Ingram protested.

“Those are just family letters — my father’s letters to mother and hers to him before they were married.”

“Yes,” said Norton, but lifted out the top packets and continued imperturbably to empty the box. He came to the bottom and still was not satisfied. With the blade of his pocket knife he lifted a closely fitted square of pasteboard which lay as a false bottom and called his assistant from the search of the second room: “Here’s something, Ashlander.”

Steve stepped forward quickly to look.

The something consisted of a pair of identical parallelograms in white tissue paper lying flat on the true bottom of the box, and Steve saw they were exactly of the dimensions of a bank note. Norton picked up one, ripped off the white tissue and exposed a copper plate displaying in reverse “Federal Reserve Bank of New York” — twenty dollars.

“Check letter A, plate number 121; Carter Glass, Secretary of the Treasury,” Ashlander announced triumphantly. “John Burke, Treasurer of the United States; the portrait is of Cleveland.”

Steve straightened with a sickening stop of his heart and faced the girl for whom, an hour before, he so confidently had vouched. No longer was she defiant; she was trembling, white as death. The two secret service men never glanced up from the plates. Each had one in his hand which he examined with swift but close inspection. They looked at each other, exchanged plates and suddenly Norton laughed aloud.

Steve started forward with hot resentment. “That’s a great way to feel about it!” he rebuked Norton. “You’ve got the goods on her, but — don’t laugh!”

Norton turned to him and sobered. “Excuse me,” he begged. “I wasn’t laughing at her — at you, Miss Ingram. Sit down, young lady,” he invited her kindly. “Sit down and tell us what you really know about this. Of course we know now that you had nothing to do with these plates here. They were planted on you. Bring her that chair, Ashlander. That’s right; sit down. You didn’t know you were taking in and passing out counterfeits either; but you do know from whom you got the last two, at least. Ashlander, get her a glass of water.”

“I’ll get it,” offered Steve impulsively. However, he let Ashlander bring it, while he himself remained beside Clara, who had sunk upon the chair and with wide eyes was staring at Norton, at himself and at Norton again.

“These plates were planted on her, you said,” Steve reminded Norton, with a flush of faith in the girl again. Not complete faith. Something was very wrong, and her own prostration confessed it. But the thing that was wrong with her was not that which had been first suspected.

Norton nodded, with more regard to the girl than to Steve, and he waited until he was sure that she had collected herself sufficiently to attend him.

“Somebody has taken considerable time and more than the usual amount of trouble to plant counterfeit money so that it would pass through your hands, Miss Ingram,” he repeated to her quietly. “He has taken more trouble to be sure that it would be traced back to you — and no further than you. Then he took the extra trouble to plant these plates here. What made me laugh a minute ago was that after taking all that trouble he made one little slip which showed us at once that the whole affair was a plant, and was planned not for the purpose of passing counterfeits but for discrediting you for some more important purpose. Do you hear me?”

“Yes,” said the girl, staring.

“What was that slip?” Steve asked, helping her.

Norton picked up one of the plates. “A very simple and natural one to a man who was not, himself, an expert counterfeiter, but a very conclusive one. It’s this — the plates, planted here, never did and never could have printed the money which this girl has been passing.”

“How do you know that?” asked Steve.

“The bad money which has been passing through her hands was all in twenty-dollar denomination of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.”

“But so are the plates.”

“The notes are excellent counterfeits, defying all but an expert; they were made from plates almost as good as the government plates — from engravings upon steel. It takes a good engraver weeks or months to make the plates that engrave money that good. These plates are not the originals; these are photo-engravings of money of the same denomination and issue which were made or could have been made in a few hours.

“We came to the hotel not only because of the report of the counterfeits, made by the Guardian Trust, but because we had received this tip anonymously early this morning.”

Norton took from his pocket and spread before Clara Ingram and Steve a slip of plain white paper on which was written with typewriter:

“If you want to find the plates which printed the counterfeit twenties passing in this city, look carefully in the rooms of Clara Ingram, who works at the Commodore Perry Hotel.”

“So we came here,” continued Norton, “expecting to hit on something peculiar and out of the ordinary line, because we already had the plates from which this very good bad money was printed. We seized them in Toledo two days ago. We knew then they couldn’t be here. What was here then? Some experimental plates engraved by the same gang or what? Nothing like that; but a plant — a plain plant on this girl. Someone wanted very much to frame her for some reason. She being a cashier, it evidently occurred to him to frame her by planting on her some of the counterfeit money which has been in circulation. To clinch the case against her, he decided to plant also the plates on her. But he didn’t have the plates. We had them, but he didn’t know it. He didn’t even know what sort of plates printed the money. He cannot be a counterfeiter himself. He did know that photo-engraving plates could easily be made, and supposed they would satisfy us. So he had these plates made, smeared them with green ink to make them look as if they’d been used, planted them here and typed us his little letter.”

“Why?”

Steve asked it, for Clara Ingram yet could not speak. As the captain’s account more and more exonerated her, only the more was she overcome.

“The reason for framing this girl, we don’t know,” Norton replied. “But she must — ask her.”

“I don’t know!” Clara cried.

“I am very sure you do know,” Norton charged her quietly.

“I don’t know!”

“I am sure you know, at least,” insisted Norton, “who gave you those two bad twenties before we came to the hotel this morning.”

“I don’t know!” cried Clara desperately. “I don’t know! I don’t! I didn’t know they were bad, I tell you! I didn’t know they were bad!”

“We can wait awhile,” said Norton considerately.

“I am quite sure I know who gave them to her,” Steve volunteered. “I am quite sure she is telling the truth when she says she didn’t know they were bad; but she does know who gave them to her. It was Jentnor.”

“It wasn’t!”

“There,” said Steve, touching her shoulder, “you’ve told us it was. I knew it anyway, Clara. After you had been warned, like the other cashiers, against notes of this denomination and issue, you would have accepted them without examination only from someone you trusted entirely; and there is no one you would have lied for, I think, but Jentnor. Jentnor is the man,” said Steve to Norton, “to whom she is engaged.”

“He’s not!” cried Clara.

“You’re not engaged to him?”

“He’s not the man who gave me those twenties.”

“Who did then?”

“Someone leaving the hotel; I don’t know who. I’ve forgotten. I’m always taking in money and paying it out. I forgot about the twenties for a few minutes. That’s all; that’s all, I tell you!”

“Did you receive any money or make change or otherwise handle money for Mr. Jentnor this morning?”

“No! No! I didn’t see him at all!”

“When did you last see him?”

“Yesterday — the day before yesterday.”

“Where is he now?”

“In his office, I suppose.”

“Where’s that?”

“I don’t know.”

Steve referred again to Norton, who quietly was watching her.

“Let us leave Mr. Jentnor out,” he said kindly to her. “Try not to think of him. Try to think of a reason why anyone — anyone in all the world — would want to discredit or disgrace you.”

She turned on Norton a face drawn with fright but honest again. “I can’t!”

“Calm yourself and try to think. Remember, no one now is accusing you — or Mr. Jentnor. Whom do you know, or with whom have you come in contact, who might have a motive for injuring you?”

“Why, no one!” she cried honestly. “I can’t think of a soul in the world.”

“You don’t,” suggested Norton slowly, “threaten anyone?”

“Threaten anyone? I?”

“I mean, you have not, either by accident or otherwise, recently come into possession of knowledge to someone’s detriment or which might be used to someone’s injury?”

“No, no!”

“Take a few minutes and try to think, Miss Ingram.”

“It’s no use trying. There’s never been anything like that.”

“You must realize that there might be such a thing,” said Norton patiently, “and you not be aware of it. This affair is surely a serious one, Miss Ingram. The time and trouble expended show that it is extremely important to someone to disgrace and injure you. Such pains are taken, usually, only by a person who is in the power — or who feels himself in the power — of another by reason of information to his discredit. You might possess such information without being aware of it, or without being aware of its power over another person. It is of such information, which may be in your possession, that I want you to think.”

“Why, I’ve never had any power over anyone!”

Norton nodded to Ashlander, who arose and went out, beckoning Steve to the door.

“We had better leave her with the captain,” Ashlander whispered. “She is very excited. Of course she is protecting someone; but for her own sake we must go ahead at once. He’ll handle her better alone.”

“All right,” acceded Steve, and went out.

On the street, where the Commodore Perry loomed in front of him, he thought of the girl’s employment in the big hotel and the bearing upon her, therein employed, of Norton’s words. Constantly, by reason of her employment, she was in contact with other employees and with guests who numbered, in total, thousands and tens of thousands; constantly, as a matter of mere routine to her — taking in money, paying it out, cashing credits and checks — she performed more or less intimate services for many people, and sometimes special services, of a particularly intimate and personal character, which from their mere frequency and repetition also passed into casual routine, making upon her memory no lasting mark. A thousand such transactions could be completed without extraordinary consequence; the thousand and first, though differing outwardly not at all from the others, might touch vitally the private concern of a guest sheltered in the hotel at a crisis of his life. Had the sequel of some such service, rendered by Clara Ingram as an employee of Stephen Faraday, precipitated upon her these events?

He hastened his steps to his hotel, his mind now on Jentnor and the girl who so defiantly and loyally had lied for him. Jentnor, Steve realized, must be a different type of individual from the man ordinarily met by a front office cashier. An attractive girl, constantly cast by her employment into contact with men away from home and traveling by themselves, learns quickly to adopt a defensive attitude of indifference; and experience often fixes this attitude within her. Steve had thought of Clara Ingram as having become indifferent to men; it was one of the reasons that he had slated her for promotion in the organization. In spite of her unusual attractiveness, Steve had thought of her as unlikely to leave the organization because of marriage. Jentnor, to have won her so completely, must be distinct from the ordinary men who lingered after paying their accounts in the hope of picking up acquaintance with the cashier.

Steve sought Claflin at once. “Do you remember this Jentnor who stayed here and got himself engaged to Clara Ingram?” Steve asked.

“Very well. I know nothing about him, but he is very likable and good-looking. English sort of chap.”

“What?” said Steve.

“Englishman in this country a few years; everybody liked him.”

Where, Steve tried to recollect, had he heard almost exactly that description of a man about whom he had inquired? Oh, it had been in Denver, at the Montview, when Goebel mentioned the English-looking, likable young man who had asked to see the register for March, three years ago. For what reason? In order to steal the book, so Goebel had thought, to alter an entry after an Englishman’s name and add “and son” between the Englishman’s name and the addition “and manservant.” Steve could not recall the name except that it was hyphenated and not at all like Jentnor. Besides, what connection could the change in the Montview’s register, of three years ago, have with this attempt to frame a front office cashier in Cleveland today?

Yet another coincidence besides this similarity of the general description of the two men came into Steve’s mind. “Let’s see her card again,” he said to Claflin, and there was the record of her employment at the Montview in Denver. In March, three years ago, at the time when the rich Englishman and manservant — accompanied, possibly, by his son and also possibly not — had stopped at the Montview, Clara Ingram had been employed there.

In little less than an hour Norton returned to the hotel, bringing her with him. The girl was pale and very nervous; she stared at Steve, but scarcely spoke in reply to his words to her in Claflin’s office.

Norton nodded Steve aside. “Call your house nurse and have her keep this girl quiet. Keep her in a room here; I’ll see that her mother is sent here when she comes back to the flat.”

“What’s she told you?” asked Steve.

“Nothing. She stuck it out that Jentnor never gave her any money and couldn’t possibly be mixed up in the plant put on her. But what smashed her up is that she knows he is mixed in it — but she’ll die before she admits it.”

“Got any better line on the reason for it?”

Norton shook his head. “We haven’t a line that leads anywhere, and I think she tells the truth when she says she doesn’t know any reason. I’ve gone over her record week by week, asking her where she was and what she was doing recently, and I can’t dig a thing out of her which would explain why anybody would want to get her.”

“I’d like to ask her one question.”

“Go ahead. The best thing you can do for her is to clear this up quick as you can.”

“Clara,” said Steve, “can you remember doing anything special for an Englishman who was stopping at the Montview, in Denver, three years ago last March?”

“An Englishman?” repeated Clara, staring.

“An Englishman — middle-aged or more,” Steve ventured, “and with a manservant.”

The girl shook her head. “No, I can’t remember anything about an Englishman then.”

“Are you trying to?”

“Certainly, Mr. Faraday, I’m trying to.”

“I know you are, Clara,” said Steve, “and you know we’re trying to help you. Have you a picture of Mr. Jentnor?”

“He never gave me one, Mr. Faraday.”

“I asked her that,” said Norton. “He wasn’t handing out his photos.”

The nurse appeared and took Clara away.

“What was your idea about your Englishman in Denver, three years ago?” Norton then asked Steve.

“Nothing but a sort of hunch.”

“The nurse, or some attendant, must stay with that girl and she must be kept here,” Norton advised. “You understand that Jentnor and some others, probably, are trying to get her. They may try by rougher means; they’ve a reason that’s big to them. And she’s still sticking to Jentnor; she might even go to him if he sent for her. You’ll have to stop that.”

“If Jentnor sends for her,” Steve assured Norton, as he started away, “you’ll know it.”

…

Norton returned in the evening. “How’s your girl?” he asked Steve.

“She’s here, and being kept quiet.”

“You haven’t heard from Jentnor?”

“No.”

“You won’t. Mr. Jentnor has got out, and so cleanly that he’s left — except on the soul of that girl — hardly a trace. We’ve had a busy afternoon; but Mr. Jentnor’s performance is now pretty plain, if the reasons behind his moves are not.

“He came here a month ago from nowhere. New York is after his name on your register; but that means nothing; and there is no Howard Jentnor in New York. He is completely untraceable before he took a room at this hotel. He told her, and also other people, that he was an insurance broker; but no insurance company knows him or has had in the last month any business whatever with Howard Jentnor. He had no office here. His business seems to have been making himself agreeable to your girl. He certainly succeeded at that. All the testimony is that he was an extremely charming gentleman, of fine bearing and excellent manners — not at all the type to pick a working girl to wear his engagement ring.

“The bottom of the trouble with her is that she knows he wasn’t the sort to want to marry her. He was, to her, the fine gentleman with his English-gentleman manners and good looks. He completely sold her; but she knew, in the back of her head, that there was something the matter with this wonderful romance. It was too good to be true. But she went into it; she was crazy about him.

“Then this struck, and she knows he handed it to her. She doesn’t know why — I believe that — but she knows that he made her love him, not loving her, but as some part of this plant of his to get her. And it’s knocked her out; but her pride, and the heart of her, won’t let her turn on him — yet.”

“No trace at all where he went?” asked Steve.

“He took rooms outside a couple of weeks ago, after he became engaged to your girl; he cleared this morning, not leaving a collar button behind him.”

“Was he in Cleveland all this last month?” asked Steve.

“No; last week he was away for five days.”

Later in the evening, with the Cleveland investigation of the affair thus at a standstill, Steve phoned Goebel in Denver.

“By the way,” he mentioned, after speaking of routine matters, “has anything new turned up on that alteration in the register you showed me?”

“Not a thing.”

“What was the name, Goebel?”

“Hougham-Stearns — L.B. Hougham-Stearns and son and manservant, London. We think the ‘and son’ was written in later.”

“I remember that,” said Steve. “What was the name of his place in Southern California? You had it in a clipping.”

“Sussex House. Why, have you got something on it?”

“No; just thinking it over,” Steve replied, and he thought over it several times that night.

In the morning Norton reported the rounding up of more members of the counterfeiting gang; he had developed no connection of the gang with Clara Ingram, beyond the fact that Jentnor had used some of the money made by the gang in the plant upon her.

Clara Ingram had no more to say; she still refused to accuse Jentnor; she could not supply any reason why he or anyone else would injure her.

Steve visited her again late in the morning. Her mother was with her and she had been crying.

“You know, Clara,” said Steve, “that whether Jentnor had anything to do with this trouble of yours or not, there must be something very wrong back of it. You want to clear that up, don’t you?”

“Yes, Mr. Faraday.”

“Try to think. Three years ago last March — it was the first March you were at the Montview, Clara — did you do anything special for an Englishman named Hougham-Stearns who was at the hotel?”

“No, Mr. Faraday.”

“He was rather an old man and sick,” continued Steve. “He had the suite on the fifth floor at the southeast corner. Were you ever called into that suite to do something special for an oldish Englishman who was sick?”

Clara’s eyes dulled with speculation; but finally she replied, “No, I don’t remember.”

“I remember something our first March in Denver, Clara,” put in her mother. “You brought home ten dollars for it. You told me about it; it was something you did for a man who was casting off his son.”

Clara’s eyes dulled and brightened. “I remember going to that room for an old man who was sick,” she said slowly to Steve. “I went there with Mr. Clover, the night clerk.”

“Why did you go there, Clara?”

“He wanted Mr. Clover and me to witness a paper for him.”

“What sort of a paper was it?”

“It was a will.”

Ten minutes later Steve phoned Norton: “I think we’ve got something now.” And when Norton came over, Steve told him what.

Two days later Steve received from Norton in New York a nine-word telegram:

“Can you come on here and bring Clara Ingram?”

Norton was awaiting them in the Grand Central Station when they arrived the following morning. He looked keenly at the pale and troubled girl, then drew Steve aside out of earshot.

“What have you?” Steve inquired.

“Not Jentnor yet,” Norton replied. “Since he passed counterfeits, among his other activities, the department wants him; that’s my excuse for staying in the case. Otherwise this case has become considerably more than a Federal matter. It’s going to be a bit hard on your girl.”

“I think she’s prepared,” said Steve.

“A woman’s never prepared for a thing like this,” returned Norton, and led them to a cab.

Twenty minutes later it stopped before a narrow-fronted house which, in spite of the incursion of business buildings in the neighboring block, still held a suggestion of the grandeur which once was the boast of lower Fifth Avenue.

Steve led Clara Ingram up the steps and Norton rang the bell. “Mr. Faraday and Miss Ingram,” he announced to the liveried servant, who admitted them and led the way up a handsome stair to the floor above, where a second servant showed them into a large room presided over by a huge old man with snow-white hair and mustache. He sat, as if on a dais, in a great chair among cushions. Steve would have recognized, if Norton had not told him, that Hougham-Stearns’ position in this household was that of a guest; he was one who, traveling, stopped more often in the homes of friends than in hotels.

“Mr. Faraday,” the Englishman greeted him, as one to whom the name meant nothing.

“And Miss Ingram,” Steve supplied, but could not see that Hougham-Stearns recollected either the girl or her name.

She in turn stared at him as at a stranger; she was shaking, Steve saw, and very white. He stood close to her.

The servant, who noiselessly had reclosed the door, came with soundless steps to stand behind his master’s chair. He also was quite plainly an Englishman, but dark-haired and with sallow skin. Norton had not entered the room.

“I agreed to see you,” said Hougham-Stearns to Steve, “on rather indefinite but authoritative information that you had something to communicate which is of great importance to myself. Recently I have received no one at all, in order to conserve my strength for my voyage home. I must ask you to be as brief as you can.”

“It concerns,” said Steve, “your son.”

“Nothing of any possible sort which concerns Ralph can be of the slightest interest to me.”

“This is a matter which you cannot very well put aside. Miss Ingram innocently has been in serious difficulties with the Federal authorities because of counterfeit money which, in our belief, your son put in her hands.”

Clara Ingram started. Steve grasped her arm, steadying her.

“I do not doubt it,” said Hougham-Stearns. “I mean I don’t doubt he did it.”

“He first became engaged to marry her.”

“I do not doubt it.”

“Apparently with no other purpose than to gain her confidence with the object of discrediting her.”

“I say, I do not doubt it. You are not the first, Miss Ingram, whom my son has involved in trouble and grief. You can accept his father’s word that, with women and men, he has been through his life a thoroughgoing rascal who has kept faith with no one. But anything he has done to you is less than he has done, more times than one, to me.”

“Miss Ingram has known him by the name of Jentnor,” said Steve. “She is not yet convinced that he has deceived her. May I ask if you have a picture of your son?”

Hougham-Stearns held his head stiffly. “I have always kept the one which his mother carried with her.” He nodded to his servant, who went out and returned with a picture in a little round jeweled frame. Hougham-Stearns ordered it given to Steve.

“Is that Jentnor?” Steve inquired of Clara, and he felt her shaking as she gazed at it.

“No,” she denied. “No; no, it isn’t.” Then her defense broke; suddenly she was so weak that Steve caught her in his arms and half carried her to a chair. “Oh, it is! It is!”

“Miss Ingram,” said Steve quietly to Hougham-Stearns, after the girl was calmer, “was one of the witnesses to your will.”

“I do not follow you.”

“You were in Denver at the Montview Hotel,” Steve continued, “with your son, and the will which Miss Ingram witnessed with George Clover, another employee of the hotel, if she remembers rightly, disinherited him.”

“That is correct,” said Hougham Stearns, “except that my son was not with me. I was there alone except for Charles.” Charles was the servant. “I had seen Ralph in New York and the latest disgraceful chapter of his doings decided me utterly to cut him off. In Denver, suddenly taken very ill, I made a will leaving my property to charities.”

“No doubt you sent the will to London, to your solicitors?”

“No. I wrote them that I had made a new will whose nature they would learn when I returned. I never returned. I still have it by me.”

“Would you mind showing it to me?” Steve inquired.

Hougham-Stearns, now intently interested, looked for his man, but the servant had left the room. He touched a bell beside him, waited, then touched it again. As the man did not appear Steve himself offered to get what was wanted; but Hougham-Stearns merely rang once more.

Clara Ingram was sitting up, wide-eyed and intent again.

“Someone is coming now,” said Steve, and opened the door, admitting Norton, who bore a light steel box, locked.

“Your man is below in the hands of two of the New York police,” Norton said to Hougham-Stearns. “However, they did not prevent his answer to your bell. They took him as he was leaving the house. Here is your box. I have also the key, taken from your servant. Shall I open it?”

“Please do.”

Norton did so, and placed the open box beside the Englishman, who immediately abstracted a folded document and a moment later another which was outwardly a duplicate of it.

“What’s this? What’s this?”

“You will find one, I imagine,” said Steve, “to be your will as drawn that night in Denver and witnessed by George Clover and Clara Ingram, disinheriting your son. The other, I believe, you will find somewhat different.”

“It is another will, signed with my name but not by me, which leaves my estate to my son.”

“H’m,” said Steve. “How is it witnessed?”

“One signature is the same as in the other — George Clover. The other name is Ida Delff.”

Steve turned to Clara. “Do you know Ida Delff?”

“She was a floor housekeeper at the Montview.”

Hougham-Stearns sank back upon his pillows. “My son has done this!”

“Unquestionably,” said Steve.

“I did not suppose I had left him power to deal me another blow.”

“You cut him off from millions,” Steve reminded him. “Undoubtedly you told him. He was not one to be passive. May I see those documents?”

Hougham-Stearns nodded and Steve examined them.

“It is quite clear now, Clara,” said Steve, putting them in her hands. He looked to Hougham-Stearns. “These must represent a very pretty bargain between your son and your manservant. About a month ago, to judge from your son’s movements, they prepared this forgery; and your son went to look up the witnesses of the original will to see if they could be bought. Evidently Clover was bought — if this signature is his. Your son went to Cleveland to investigate Clara Ingram and plainly gave up the idea of buying her. So he did not put her name on the forgery; he put the name of another employee of the Montview, who evidently was bought and would swear in court that she witnessed your will.

“Everything was then arranged for the substitution of the forgery for your original will in the event of your end, except the evidence of this girl here who had witnessed the original. Your son personally took care of her. He made love to her to get her confidence; for he schemed to put her out of the way for a time in a Federal prison and so discredit her that her testimony, if offered against the forged will, would be considered untrustworthy.”

“By counterfeit money, you say?” Hougham-Stearns gazed at Steve with gaunt eyes.

“He seems to have obtained some counterfeit money which was circulating in Cleveland and planted it upon the girl; he also manufactured other evidence,” Steve said. “A bit of poetic justice, of the sort which Captain Norton tells me is common in such cases, is that this was unnecessary. Miss Ingram had quite forgotten the incident; and if she had been reminded of it by reading that he had inherited your property, she would probably have thought merely that you had made another will.”

“But how,” asked Hougham-Stearns, “since you did not know his name, did you trace him to me?”

“He had manufactured still another bit of evidence to support his case. Knowing that he had been on bad terms with you, he wanted it to appear that, at the time of making your will, you were together; so he altered the register in Denver to insert ‘and son’ after your name. It was this which first called attention to him and brought you into the case.”

“That is exactly like Ralph,” Hougham-Stearns said, asking no more. “Especially his ingratiating himself, for ulterior purposes, with this young lady. I would like to do something for her. I would like to compensate — ”

Clara Ingram, with eyes filled with tears, shook her head.

“Yes; I will insist on something. To you, Mr. Faraday, I am grateful. You have gone to considerable expense and great personal inconvenience to do me a service.”

“Service?” Steve picked up the word. “You were a guest at the Montview three years ago, and the Faraday management aims to offer every possible service to its guests.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now