Sophie Kerr was a prolific author of short fiction for the Post, publishing several stories in the magazine each year through the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s. Her fiction focused on cultural divides between urban and rural communities as well as those separating men and women. The Sophie Kerr Prize is now the largest undergraduate literary scholarship in the country. Her story from 1932 follows an eligible bachelorette’s complicated romantic decision through the lens of cuisine, proving that “human felicity is made up of many ingredients, each of which may be shown to be very insignificant.”

Published on February 13, 1932

Miss Mabel Arden stood before her mirror and purred as she looked at herself in her new black velvet dress and the little black velvet hat cocked over her right eye. Slender! Sylphlike! A proper indentation at the waistline instead of a mean little bulge! It was really wonderful what exercise, and an iron horse of a masseuse, and going without sweets like a martyr, had done for her. She could easily pass for thirty or less, and not in the dusk with a light behind her, either, but in the full stare of unshaded electric lights, or a harsh white sunbeam. And Mabel had been born just on the wrong side of 1890.

Savilla came in at this moment. She held a square white box in her hand. “Mist’ Simms come,” said Savilla. “He brought his reg’lars.”

Mr. Simms’ reg’lars was a cluster of gardenias, flowers as white and sweet as the flesh at the point of the v neck of Mabel’s new frock. Mabel pinned on the flowers carefully, still regarding herself with intense pleasure and appreciation.

“Get my gloves and my short black fur coat, please, Savilla,” she said. “And my little black-and-gold bag.”

Savilla obeyed. “You look manifisum!” she commented. “Slickes’ gownd you evah had. Gonta knock Mist’ Simms a loop, y’are, Miss Mabel.” In her expression there was a certain speculative quality. Mabel knew that Savilla was wondering how soon that dress would descend to her, and whether she could get into it.

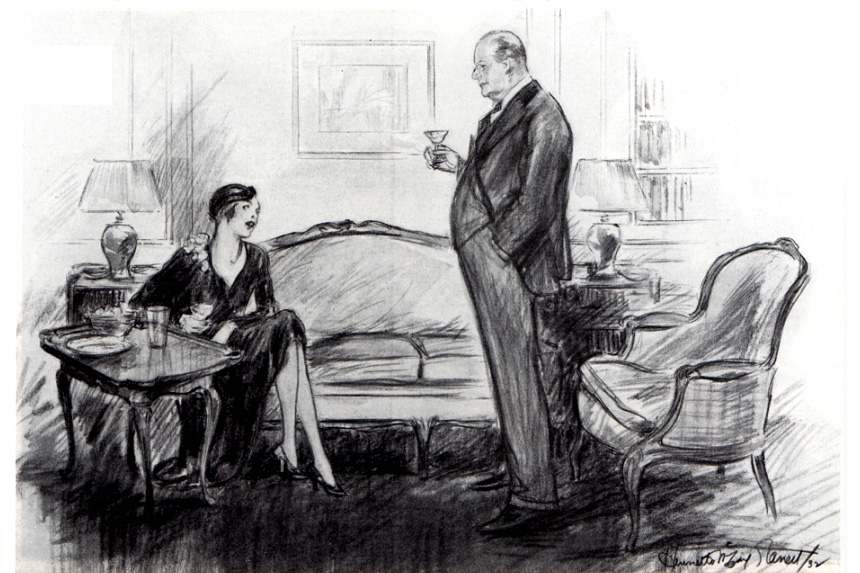

“I won’t put on the coat,” said Mabel. “Leave it in the hall with my gloves, and bring the shaker and glasses and ice into the living room right away.” She turned slowly from the mirror and went in to meet Edward Simms and knock him for a loop, though she knew it wasn’t necessary. She could knock Edward Simms for a loop in the oldest, dowdiest rag she possessed. He was like that. He was, in fact, so devoted, and had been so devoted for so many years, that he might be said to be permanently looped by Mabel.

Still, it was nice to see his face as she entered in her black velvet magnificence. It changed from his ordinary welcoming smile to a look of admiration that was downright abject. “My Lord, Mabel!” he exclaimed. “How do you do it? Every time I see you you’re younger and more beautiful!”

“It’s my new frock.”

“It is not! It’s you. Gosh, but you’re lovely! I’m getting to be a fat old man, but you’re receding into your teens.”

Savilla appeared with a tray on which were a small silver shaker, a bowl of ice, two glasses, and a plate bearing four tiny canapés. Mabel unlocked the dignified mahogany bookcase — it had held her great-grandfather’s law library once upon a time — and took from behind its doors of brass-wire mesh and pleated green silk two interesting liquid containers, one square and one round. These she handed to Edward Simms, who received them carefully and proceeded to measure, with deft exactness, two portions from the square container and one portion from the round.

He looked up inquiringly. “No absinth tonight?” he said.

“I forgot,” said Mabel. She produced another container, and with a solicitude bordering on reverence, Edward doled out eight drops. Then was heard the tringle-trangle of ice against silver, and then the two glasses were filled with a cold, pale yellow fluid, teasingly aromatic, tempting the eyes, the nose, the palate.

“To the most beautiful woman in the world,” said Edward. He sipped critically. “It’s perfect, like you,” he said. “It’s just right.”

He went on talking. Edward Simms always talked a good bit.

“I know nothing more restful and agreeable,” he said, “after a hard day’s work than to come into a room like this, and look at a wonderful creature like you, Mabel, and taste a drink like this, all as a preface to a very good dinner at Rovi’s. Call me a sensuous pig if you like, call me a hedonist or a materialist or what not, but that’s the way I feel, and I glory in my shame. I only wish I could look forward to the same delight every night of the world. Why won’t you marry me, Mabel? I’ve dangled so long.”

“Are you going to begin that all over?”

“Begin it over? When did I ever end it? We’re so congenial, Mabel. And I’m not a bad sort; you know it. And I’m so crazy about you, always have been, always will be.” He paused, shrugged. “You’re going to laugh at me and turn me down again. All right, but I shan’t lose hope until I see you married to someone else. And even then there’s Reno.”

“If you’ve finished your nonsense, let’s go,” said Mabel.

Edward’s car was waiting, a trim sedan with extra cushions. It had been raining and the streets were polished gray steel, barred and spangled with gold from the lights, and the air was fresh and cold. Mabel leaned back and relaxed. There was something she wanted to tell Edward Simms, but it wasn’t kind to spoil this hour. She looked at his profile as he sat beside her driving. Kind, good, congenial, funny, and fairly handsome, though a little too fat. “He eats too much,” thought Mabel. “Nobody can feel romantic about a fat man. He talks about eating and drinking, and then proposes to me. He ought to see how impossible he makes it.” She gave a sigh for Edward Simms’ impossibility. He would feel it when she told him her piece of news. Far better wait until after dinner.

At Rovi’s they were received with acclaim, Signor Rovi himself ushering them to their table, the best in the house, properly lighted, shielded from drafts, removed from the path of passing waiters and far from any service table. There was no music at Rovi’s, no entertainers. People came there to eat well, and were never disappointed.

“Have you ordered?” asked Mabel, her interest quickening. She had lunched on a lean chop and a sliced tomato, and the delicious savory odors all about made her feel like a lean chop herself. Besides, no sane woman could feel anything but interest in a dinner ordered by Edward Simms.

“Yes, I’ve ordered. I hope you’ll like it.”

“I know I’ll like it,” said Mabel truthfully. “Nobody orders a dinner as you do, Edward. You know a great deal about it.”

“You know just as much. Think of the dinners we have at your apartment. Savilla’s a marvelous cook, but you’ve trained her.”

The waiter was serving caviar — true caviar, richly gray black, clinging to the spoon. Squares of hot toast and halves of fresh-cut lemon and grated mild onion and egg came with it. Also a pepper shaker containing cayenne. At this, Mabel looked surprised. “Try just a grain, Mabel,” urged Edward. “It’s not orthodox, I suppose, but it’s exciting.”

It was exciting. It was stimulating. “You’re right, Edward, as usual,” Mabel granted.

After the caviar there were cups of consommé Bellevue, the essence of clam and chicken, the spoonful of rich cream, all perfectly blended as a major chord of music. Ripe olives, supersize, shining, juicy, and titbits of celery heart accompanied the soup.

“But no toast or crackers or bread,” said Edward firmly. “People who eat bread with soup are all wrong, in my opinion.”

“I’m willing to forgo the bread, but I don’t entirely agree with you. Take an old-fashioned vegetable soup, for instance — ”

“But that is not a soup, Mabel. Old-fashioned vegetable soup is a meat-and-vegetable stew, and bread goes with it perfectly. And of course there are soups which contain toast or crusts as part of their ingredients, and that’s all right. But don’t muss up a consommé like this with anything starchy.”

“It’s true. And of course a purée is enough in itself; any bread just makes it stodgy. Oh, dear, this is so good. You make it very hard for me to stay thin, Edward. Do tell me what’s coming next?”

Her question was answered by the waiter, who approached, bearing a covered copper dish. He opened it and held it for her inspection. There, each on its own toasted pedestal spread with giblets chopped to paste, were two plump partridges, wrapped in vine leaves and the thinnest, most wafer-like slices of salt pork, done to a turn in their own juicy steam.

“And they’re just right,” said Edward, sniffing. “Not too high. People who eat very high game are simply scavengers! Pardon me, Mabel, for using the expression.”

Brown toy balloons of soufflé potatoes and a spoonful of tart grape jelly were the partridges’ companions. Mabel could not help eating everything, picking her bird to the bones, its supporting canapé to the last crumb. Edward Simms was likewise omnivorous. They ate leisurely, taking the full value of each delicious morsel. But if Mabel was silent, she was thinking, and her thoughts were divided. It was going to be harder than she had expected to tell Edward what she must tell him, and she was glad that she had not done it as they drove down town. It would have been a crime to bring to this meal any emotion but enjoyment.

After the partridges came a green vegetable, young, tender, green string beans, cut into slivers and cooked only the magical few moments to bring out all their infantile delicacy, then touched with melted sweet butter, and served piping hot on hot plates.

“I hesitated between these and a salad,” said Edward, “but they had nothing very distinguished in the way of salad greens, so I thought these would be better.”

“These are just right,” said Mabel.

“I’ve ordered no dessert,” he went on, “but there’s a marvelous poached pear with almonds and lemon Rovi bragged about, or frozen fresh pineapple.”

“What are you going to have?”

“The pineapple, I think, and we’ll make the coffee at the table. I’ve told Rovi not to grind it until we are ready for it.”

“Edward,” said Mabel gravely, “these little matters of grinding coffee and choosing a dessert and working out a menu are very important to you, aren’t they?”

Edward met her gravity with an impish twinkle.

“My dear Mabel, I like to dine as well as I can. So, I am safe in saying, do you. I don’t think it reprehensible to make all my meals as interesting and enjoyable as possible. Let me remind you that we mortals spend approximately one-eighth of our waking hours at table, supplying our bodies with their needed fuel. And if we do not supply our bodies with their needed fuel they balk or stop on us, and we — well, we’re done for. Taste is one of our five senses. My palate likes a good meal as much as my hand enjoys touching an agreeable surface, or my nose smelling those gardenias, or my ears hearing your very charmingly modulated voice, or my eyes resting on your most attractive face. I see no harm in good eating, as long as I make it a means to life, and not an end. Forgive me — you brought it on yourself by that scolding look in your eyes.”

The coffee machine was placed on the table and Edward watched the waiter measure the water and light the flame. Then he went on: “You’re the only woman I know, Mabel, with really civilized ideas about and appreciation of good food. You’re the only woman I know I’d trust to order my meals. We have many other small, livable tastes in common. And I don’t see why you won’t marry me. It isn’t only that I love you — ” He paused, and for an instant Mabel saw Edward Simms strangely changed from the man she knew into a wistful, imploring boy. And in that instant she realized she hadn’t the nerve to tell him what she must tell him — not tonight, at least. That boy she had seen would be too easily, too much hurt. She must contrive some way to let him find out for himself; he would bear it better if she didn’t put it into words.

“What d’you think about going to a movie, or to see the last half of the hockey at the Garden? You’re really much too elegant for either, but any show we’d go to would be half over,” said Edward as they finished their coffee: The wistful boy was gone. Edward the middle-aged was selecting a cigar with absorbed inspection.

Mabel sighed. Life, even when one is slim and dressed in new and successful black velvet, can present complications. “I’d like a movie,” she said. “A harrowing one, where I could cry.”

“And hold my hand?”

“If it’s sufficiently harrowing,” said Mabel. It wasn’t any use trying to be serious with Edward. She might as well enjoy herself and give him a good time. It would, she thought, probably be their last.

In the theater she could not keep her mind on the picture. Edward had wangled the best seats in the house — he always managed to do that, no matter how big the crowd was — and he had brought her through the mob without letting her be pushed or hustled. It was a Dietrich picture, and Mabel was crazy about Marlene; indeed, it was envy of Marlene’s thin and shapely legs which had helped her through this last hard two weeks of reducing. But now she regarded Marlene and her legs with indifference. How — how was she ever going to break it to Edward that Dean Kennedy was coming back!

Dean Kennedy, after fifteen years of absence! Dean Kennedy, her one great romance, her dream, her ideal! Dean Kennedy, so tall, so dark, so thrilling, black hair flung back wildly — not brushed flat like Edward Simms’ thinning locks — brown eyes that laughed and teased and mocked and drew her heart helplessly to him. Dean Kennedy was coming back, and what was more to the point, he was coming back a widower, for that silly moon-faced Cara Mai Kennedy, who had simply tricked him into marrying her when he was a mere twenty-five, not old enough to know his own mind — Cara Mai had, according to the letter Dean Kennedy had written Mabel, “passed on into the beyond” more than twelve months ago. So he was coming back to see all his old friends, and, again quoting the memorable letter, “most of all, I want to see you.”

It was this letter and the two which had followed it that had sent Mabel to the rowing machine and the masseuse, had kept her steadfast on chops and sliced tomatoes, and finally, as the moment of Dean’s coming drew near, had caused the purchase of the velvet dress. In all these fifteen years she had not seen him or heard from him. Dean and his Cara Mai had dwelt in Chicago and had not been very well off, Mabel imagined, nor had Dean been very successful; but that, of course, was Cara Mai’s fault; she was not the sort to inspire a man to his best efforts. Mabel tried to think kindly of Cara Mai when she thought of her at all, but she suspected that she had been a drag and a burden.

Ah, well, it didn’t matter. Mabel had a nice little patrimony, and that would ease things for Dean at first. Afterward, he would naturally make great strides toward success, for she would aid and encourage him. She would understand him. Look at Edward Simms — how well he had done. Why, Edward was positively a rich man, and if Edward Simms could be successful, how much more successful Dean Kennedy could be! All their crowd had looked to Dean Kennedy to do great things; they knew he had it in him; and if he hadn’t done them, circumstances or influences or a certain person must have prevented him.

Having thus brought her thoughts back to Edward Simms, she began to remember how devoted he had been during all these far-away, silent Chicago years of Dean Kennedy; how truly devoted in every way, not obtrusively but steadily and firmly. No matter what happened, Edward was always there, taking her places, bringing her flowers, advising her investments, and helping her make out her income tax; in every way surrounding her with attention and solicitude. Everyone they knew asked them to parties together, and took it for granted that it was a permanent attachment, if not an actual engagement. Mabel had a guilty feeling that she had accepted far too much from Edward, but she tried to abate this by reminding herself that he had offered much more. Certainly their companionship had been delightful. Edward knew his way about. He knew how to do things.

It came to her in a flash of divination — the way to reveal Dean Kennedy to Edward. She would give a dinner — a dinner for six, which was the best number for Savilla to manage — and ask both men, a married couple — perhaps her Cousin Rufus Arden and his wife — and another woman — that nice blond Mrs. Tree who did bookbinding. She would plan a truly wonderful dinner as a farewell tribute to Edward, but there and then she would make her feeling for Dean Kennedy unmistakably clear. Edward was not an insensitive or stupid man. He would take the hint. He would bow himself out of the picture without any painful explanations, arguments or emotional farewells, and he would, she felt, thank her for having spared him.

Caution prompted Mabel at this point and reminded her that in case Dean Kennedy was not coming on with serious intentions and should go away without asking her to marry him, this course made it possible for her to continue on with Edward as before, since nothing would have been said. She therefore clinched it in her own mind that she must know Dean’s feelings accurately before she arranged to dispense with Edward. No matter how much she glowed and thrilled over Dean Kennedy, she owed it to herself to learn if he was glowing and thrilling in return, before she opened her door and deliberately set Edward and his kindness on the cold steps outside. It occurred to her that in all probability nice blond Mrs. Tree would like to make a grab for Edward if she found him available. She rather hoped this wouldn’t happen. Edward would never be happy in a bookbinding studio; he would hate the smell of glue and leather.

It was all thought out by the time Marlene had given her lovely legs their final extended showing, and Mabel was so pleased with her neat swept-and-garnished state of mind that she was particularly agreeable to Edward all the way home. She would almost have liked to kiss him good night, she felt so sorry for him, and so sympathetic, but since he didn’t make any motion toward kissing, she couldn’t very well do it; and besides, he might have misunderstood and not known it was sorrow and sympathy which prompted her demonstration. When she entered her own hallway she was glad she hadn’t kissed Edward, for there, on the table, lay a telegram from Dean Kennedy:

ARRIVING TOMORROW SIX PM STOP YOU MUST HAVE DINNER WITH ME STOP WILL PHONE AS SOON AS I GET TO TOWN

Only by resolutely counting several zillion sheep did Mabel get any slumber that night, and she couldn’t have counted so many had she not pictured herself haggard and dull-eyed for meeting Dean Kennedy the next day. Once asleep, however, she dreamed blissfully of orange blossoms and wedding bells until so late in the morning that Savilla came in to see what was the matter. And over her cup of coffee without cream and sugar, her one meager bit of whole-wheat toast and her six unsweetened prunes, Mabel continued to dream. Savilla noticed it.

“You mighty swimmy this mawnin’,” she said — “mighty swimmy an’ smily. Wisht I felt so good. Wisht I hadn’t played de numbahs yestady. Los’ fo’ dollahs, quicker’n scat.”

“I’ll give you four dollars, Savilla,” promised Mabel, “and that blue crêpe dress of mine with the rhinestone buttons.”

“An’ de blue hat too?” asked Savilla cagily.

“Yes. And the blue bag, and the blue-and-white-striped scarf.”

“You musta come into love er money, Miss Mabel. That blue dress pret’ near new. Lawd knows I need clo’es, but they ain’t no need for you to divest yourself to nothing thisaway,” remarked Savilla, meanwhile making haste to remove the blue dress and hat from the closet.

“Take it along. I hope it brings you luck.”

“Yas’m, hope it does. Now, what you goin’ to have for your dinner?”

“I’m going out for dinner, Savilla.” She almost trilled the words, she was so happy.

“Yas’m. Want a li’l’ sumpin serve’ befo’hand, as usual?”

“Yes. No. No, I think not. Or, I’ll tell you. Fix the tray and leave it in the ice box, and if I want it I’ll serve it myself. And you can go out.” She didn’t want anyone, not even Savilla, near for that first moment.

By telephone she ruthlessly called off all the day’s engagements. There was a meeting of a hospital committee, and another of the executive board of the Working Girls’ Club, a bridge luncheon and a tea at which she had promised to help receive. Mabel listened unmoved to the reproaches of fellow workers and hostesses, disposed of them without a qualm. This being done, she proceeded to devote the time before Dean Kennedy’s coming to a prolonged, restful beautifying. A swim and massage, a manicure, her hair shampooed and dressed, a pedicure, vibration for shoulders and arms, oil rub for elbows, mud pack for her face — Mabel did everything on the list and returned home about half past five to dress. She had told Savilla to give the apartment an extra cleaning and put roses and white narcissi on the piano and the desk — not too many, just enough to look charming and homelike. Everything being ready, she again put on the black velvet dress and sat down to wait.

The telephone rang at half past six and she flew to answer it. It was Dean Kennedy. His voice sounded just the same; she could hardly control her own to reply. He would, he said, just dash over to the hotel and clean up, and then he’d be right along. He wouldn’t be ten minutes. Mabel put down the receiver with trembling hands. In ten minutes — ten minutes — after fifteen years! Now that he was so near, she could not believe it. She ran her dryest, most indelible lipstick over her lips, powdered her nose, smoothed her eyebrows, put a dot of her most treasured perfume on each ear lobe and one on her bosom, regarded her hair at every possible angle and questioned herself in the mirror. Was she pale? Did she look too excited, too expectant? She didn’t know; she couldn’t tell. She walked about, breathless with anticipation, but at the sound of the doorbell she pulled herself together. “Be your age, Mabel,” she whispered. “Be your age. Have some dignity.”

She walked slowly to the door and opened it. “Why, Dean,” she heard herself exclaiming in a flat, conventional voice, “how quick you were! You said ten minutes, but I didn’t believe you. Come in.”

He was just as tall, just as handsome as ever, his black hair still waved tumultuously, he was still laughing and gay and impulsive.

“Gosh, Mabel,” he said, “it’s good to see you! We’ve both changed a lot, of course, but you’re awfully good-looking yet, even if you’re not the girl you used to be. And what a pretty little apartment you’ve got here.”

“Y-yes, it’s very comfortable.”

“And we’re going out to dinner, just the way we used to do.” He laughed. “And I can’t afford to take you to a better place than I did then. Hope you don’t mind. I never was much of a money-maker, Mabel. We’ll have to go to some cheapish joint, my dear, and you looking like a million dollars too. Shall we push off? I’m starving.”

He had always been like that, she thought fondly — frank, open as the day. How sweet of him to remember and allude to the few times he had taken her out in the long ago. When she went to put on her coat she discarded the velvet jacket and took a plain, long, black cloth, and she laid the velvet hat aside and pulled on a green felt that had seen much service. It wouldn’t do to embarrass him with her finery. Query: Would it embarrass him? She didn’t know, but she wouldn’t take the chance.

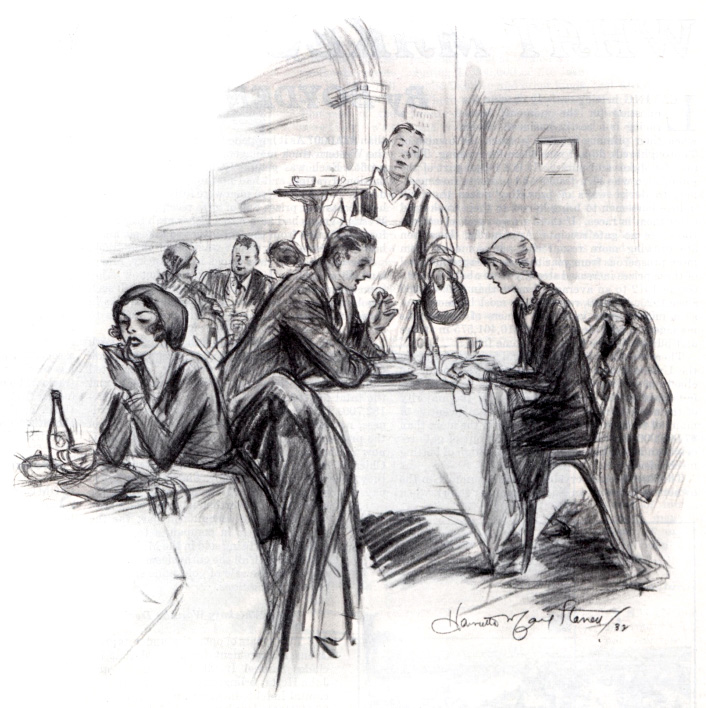

“Now,” he said when they were on the street, “we’ll walk to the corner and get a downtown car. Funny, the city’s changed so much I don’t know my way around, but there used to be a lot of table-d’hotes in the Forties and Fifties. I suppose there are some left. Or look” — he pointed up the avenue — “what about that place? It looks all right.”

Mabel opened her lips to say that it was an awful dump and she didn’t believe there was a thing fit to eat ever to be had there, but she closed them again without speaking. It didn’t matter. Nothing mattered but that Dean Kennedy was beside her, his hand on her arm. So she went along with him into the noisy restaurant, glaring with lights, reeking with stale food odors, unmistakably what he had said he could afford: a cheapish joint — a very cheapish joint.

“This is fine,” said Dean, and took a table nearest the pantry door, so that every waiter passing in and out must graze them. He picked up the scarred menu as an unshaven bandit with spotted apron and shirt front came for the order.

“The table-d’hôte is only sixty cents here,” said Dean beamingly. “Vegetable soup or fruit cocktail, choice of baked bluefish, roast pork, pot roast with noodles, or corned beef. Boiled potatoes, cabbage and succotash, salad, and for dessert, apple or squash pie, rice pudding and mixed ice cream. Coffee, tea or milk. I’ll have the soup, the roast pork and vegetables, and apple pie and a glass of milk. What are you going to have, Mabel?”

“I think I’ll have the fruit cocktail and — and the — the pot roast — and salad — and no dessert,” said Mabel, trying not to shudder. “Just black coffee.”

“O.K., chief,” said Dean; then to the waiter: “Rush the stuff right along, boy.” He tossed the menu card aside, put his elbows on the table and smiled at Mabel. “A nice cheery little place,” he said. “But after all, we didn’t come here just to eat. Let me look at you, Mabel. What have you been doing with yourself all this time? You wrote me that you were on committees and things! Not much of a life, that, I should think. But you haven’t lost weight on it. . . . Ah, here’s food, and my soup has the waiter’s thumb in it. I always did like waiters’ thumbs.”

“Send it back,” said Mabel faintly. It made her sick to look at the greasy, tepid fluid.

“What for? It’s all right. Quite a good thumb, in fact.”

The bandit grinned at Dean knowingly. He banged down before Mabel a small glass dish containing a sliver of peach and a sliver of pear, a segment of pineapple and half a lurid aniline-red cherry. Then he brought a basket containing three broken gressini and a twist of grayish bread, slashed twice for breaking, served two pieces of doubtful butter, filled their glasses and retired.

Dean seized the bread and broke off a hunk and began on the soup. Gingerly Mabel lifted a spoon to attack the alleged fruit cocktail, then changed her mind and wiped it hard on her napkin.

“Dean,” she said, “what have you been doing all these years? That’s what I’m interested to hear.” She thought, “If he talks, I won’t see him eating soup off the point of his spoon.” But it was not much better when he began to talk. He hadn’t, it seemed, had a very good time of it. Not that he hadn’t worked; he’d simply slaved, he’d worn himself out in devoted loyal service to one employer after another, but he never seemed to get on. He didn’t care, he assured her. There were so many good things in life besides money. He’d always had friends — good, kind, devoted friends. Every time he had lost a job he had the satisfaction of knowing that he left behind him associates who sided with him and felt he’d been unjustly treated or unappreciated.

As he talked, Mabel felt herself warm with sympathy and understanding. How terrible that he should have been so treated — how terrible, how wicked! She would have liked to take his unworthy employers and push them into the river! She listened avidly to every detail; she murmured and clucked with indignation. She said “ohs” of horror and “ahs” of pity. She was his partisan, his defender. And when a mean, little, irrepressible imp of observation within her asked her if he had always taken such huge bites and chewed with his mouth open, she shoved that imp aside and forgot him.

She herself could not eat. The pot roast had been poor meat to begin with, and cooking had worsened its estate. The vegetables were watery and heavy. The coffee, to put it concisely, was vile. Dean sat there lapping up everything, though his order of pork looked more deadly than the pot roast, and the apple pie was a truly fearsome pastry. She could have wept for him. Poor dear, to have his taste so vitiated, so depraved. But never mind, there was her dinner party to come, and she would show him what a dinner should be. With his naturally fine instincts, he would instantly grasp the message she intended to convey.

“Do you mind,” asked Dean, “if I take your butter? They’d probably charge for an extra portion.”

She passed him the butter and did not tell him that it was not butter at all but a substitute, and sadly watched him eat it. “Let’s go back to my apartment,” she said. “I’ll make some coffee for you.”

“What’s the matter with yours? Isn’t it all right?” he asked with surprise.

“Oh, quite, but I believe I can make better,” she assured him brightly. “I have a maid who’s a very good cook, but I do a bit myself sometimes. I enjoy it.”

This remark turned Dean’s mind to Cara Mai. All the way back to the apartment he told Mabel what a wonderful little woman Cara Mai had been, how domestic in her tastes, what a good cook, how well she had managed on his limited income. Mabel listened to this also, but not with the same interest she had given to the saga of his business career. She was glad to escape to her kitchen and start the promised coffee.

While she was doing this she discovered that she was very hungry, and she opened the ice box, where she saw the cocktail tray and the anchovy canapés she had told Savilla to prepare and then had forgotten. Mabel ate them all and was glad to get them. They strengthened her. When she carried in the steaming, bubbling coffee she felt equal to hearing more about Cara Mai.

“Now,” she said, “we’ll be quite cozy. Perhaps you’ll have a drop of liqueur with your coffee. I have some Marc de Bourgogne — the real thing, and very old — and if you’d rather have something sweet, I’ll give you either Strega or green chartreuse.”

“No, thanks,” said Dean. “I don’t care for anything. And give me only half a cup of coffee, Mabel. The darned stuff keeps me awake.”

“Half of these tiny cups won’t keep you awake; besides, this is fresh made. It’s coffee that has stood too long that keeps people awake.”

But he would not be persuaded, and he took only a swallow of the half cup she gave him, after it had become tepid. It spoiled Mabel’s enjoyment of her delicious brew to see him. Still, it was Dean Kennedy, and he was here in her own apartment with her, after the long, long time of separation. She reminded herself that this alone ought to make her madly happy.

He had gone back to telling of his various jobs and how they had disappointed him. Mabel was no fool, and she recognized a familiar note. In her social-service work she had met many men and women who, with the best intentions, were never able to cooperate, who objected to everything proposed and argued endlessly about the smallest of points, who could not submit to the elastic give and take which measures the success of any group of human beings associated for one purpose. She did not want Dean Kennedy to seem one of these troublesome beings, but common sense forced her to acknowledge that in a business organization, where certain authority must be respected and obeyed, Dean might, he inevitably must be, difficult to handle.

But now he turned to telling Mabel what she most wanted to hear. “You must know why I’ve come on here,” he said. “It was to see you. I’ve always thought of you a lot, Mabel, but in a nice way. Not in the least derogatory to Cara Mai, you understand, nothing to which she could have taken exception, even if she had been able to read my mind. As a matter of fact, Cara Mai used to speak of you every now and then.”

“Did she? What did she say?”

“Well, it sounds rather conceited, I suppose, but you mustn’t take it that way. Cara Mai was a good bit of a tease and she always maintained that you liked me a good bit.” He laughed his engaging, boyish laugh. “I hope it’s true, Mabel. You do like me, don’t you? I’m counting on you liking me.”

Mabel struggled between annoyance with Cara Mai and gratification. “I do like you, Dean,” she said at last, generously. “Cara Mai was right. I like you very much.”

Dean reached over and took her hand.

“That’s sweet of you, Mabel. I hope it means to you what it means to me. You understand me, don’t you?”

“Y-yes,” said Mabel. Was this commonplace phrase a proposal of marriage? It must be. It couldn’t be anything else.

He let go of her hand and rose. “Then that’s all right, my dear. Now I’ve got to run down to Philadelphia for a couple of days — I’m looking into a proposition there — but I’ll be back on — let me see — on Friday, and I’ll call you up as soon as I get in. Couldn’t we have dinner together that night?”

“I’d like to have a little dinner party here, Dean, for you — some of your old friends. I thought of Rufus Arden, my cousin — you remember him and his wife Polly, don’t you?”

“Of course I do. I’d love to see them.”

“And — and Edward Simms. You remember him?”

“I should say so! How is he, anyway? He was always such a stodgy old slowpoke — sort of dumb, but a good sort in spite of it. He’s married, I suppose.”

“No, Edward isn’t married.” She didn’t want to expatiate on that. “Then I’ll ask another woman. If I can find anybody of the old crowd I’ll get her, but if not, I know a sweet little Mrs. Tree; she does bookbinding — ”

“That’s odd,” interrupted Dean. “Cara Mai was so interested in bookbinding.”

“We’ll have dinner at quarter of eight.”

“Isn’t that awfully late?”

“Oh, no! Most people dine at eight unless they’re going on to the theater.”

“I like dinner at half-past six, or seven at the latest. However, for once it doesn’t matter. Goodnight, my dear.” Before she knew it, he had swept her into his arms and kissed her twice. And he was gone before she could say a word.

As Mabel looked back over the evening, she became conscious of the fact that she was not rapt in the ecstasy she had anticipated. She knew she ought to be rapt in ecstasy. Dean loved her, he had asked her to marry him, or had fully implied it, and he had kissed her. Why — why wasn’t she satisfied; why wasn’t she putting vine leaves in her hair and waving banners and dancing and caroling supreme joy? She was forced to realize that the most likely reason for her dereliction was an attack of acute indigestion, and as she dosed herself with hot water, bicarb and peppermint, with just a drop of spirits of ammonia, she kept going farther and farther down from the proper pinnacle of happiness, and thinking of the vile dinner she had eaten, and the viler one she had watched Dean eat. It also occurred to her that never in all the times she had dined with Edward Simms had she been afflicted with indigestion of any kind. As she filled the hot-water bag to lay it upon her aching stomach, she was horrified to find that she was contrasting Edward’s entertainment of the night before with what Dean had offered this evening, and finding the first vastly superior.

“But with the dawn,” as says the popular song, “a new day is born,” and Mabel rose blithely, without indigestion and without those treasonable criticisms of Dean which had bothered her. She could see clearly now that Dean’s unfortunate tastes and habits would vanish away as soon as she demonstrated better ones to him. So, telephone in hand, she summoned the desired guests for her dinner on Friday night, and then proceeded to collogue with Savilla on the menu. This had assumed a double importance, for not only must it be a fitting vale to the advanced gourmetism of Edward Simms, but it must also be an ave to higher and better ideas of dinners for Dean Kennedy; an introduction to proper eating which would inevitably lead him into permanent acquaintance with it.

The two days before Dean’s return passed like two minutes to Mabel. There was her own new status of an engaged woman — practically engaged, that is — and the coming true of the one sentimental dream which had kept her from marriage until this time. She thought a great deal about her future with Dean, and she was surprised to feel numerous small doubts and uncertainties about it. She didn’t, somehow, seem well-acquainted with anything but his appearance. He looked just as he used to, but when he talked he was a stranger, and not a particularly endearing stranger at that. Assailed by such notions, Mabel decided that it was far wiser to concentrate on planning her dinner. So she filled up her time with scurrying about markets and delicacy shops, talking to Savilla, trying out various effects in table setting, arrangement, and choosing which of her four evening gowns she would better wear. The newest of the lot, a sapphire-blue velvet, was too exhilarating in color and too formal in style for a small home dinner. This left one of those black-lace standbys such as every woman keeps for rainy evenings and dull parties, an orchid crêpe, out-of-date, but very becoming, and an eggshell satin which had been her best last year and was still in style and good condition. Finally she selected the orchid crêpe; its delicate tone would be regretful for Edward and hopeful for Dean, and it wasn’t short enough to be quite passé. “Now that I am slimmer it will be longer,” thought Mabel; “hips do take up skirts so dreadfully!”

So, on the night of the dinner she put on the crêpe and a twisted string of fine amethyst beads caught with a gold flower. She covered her table with a fine filet cloth and set it with creamy old queen’s ware service plates and thin, pinky, amethyst glass. Pale pink lilies in a Lowestoft bowl for centerpiece, and her four Old Chelsea figurine candlesticks with tall cream candles gave a note of naïve gayety. But not too gay; all the color was low key; it did not hit the eyes, but had to be looked for; yet when observed, it was gratifying. Mabel felt satisfied with her table.

Her living room looked very well, too, for Edward Simms had sent her a quantity of roses and she had put them into deep tumbler-like vases of yellow Spanish glass. He had also sent a spray of orchids for her to wear — two perfect mauve blooms, just as if he had known what a harmony they would make with her dress. It made her sad to think these were the last flowers she would ever receive from Edward; he always chose flowers so charmingly. Poor Edward — would he, she wondered, be very much cut up when he knew? She wondered so much about it she forgot to be disappointed that there were no flowers from Dean; though on such an occasion he might very well, even though poor, have managed a small tribute.

Cousin Rufus Arden and Polly were the first to arrive, and then came Mrs. Tree, looking young and innocent in bright baby blue, which only a fresh complexion can stand. Polly Arden was in exotic scarlet. Between the two Mabel’s mauve was just a bit washed out. It wasn’t auspicious to have her two women guests fade her away, but she tried not to mind. Edward and Dean came in together; they had met, it seemed, at the entrance downstairs and were so jovially renewing old acquaintance that they didn’t pay the attention to their hostess which the occasion merited — at least Dean didn’t. Edward, naturally, didn’t yet know what the occasion was.

When Savilla’s sister, Pearlie, waitress by the hour, brought in the tray, Dean waved the glasses away. “Never touch the stuff,” he explained. “Not principles, merely stomach. The very smell of it makes me sick.”

“You’re an unfortunate man,” said Edward. “I sympathize with you, but I will gladly drink your share, provided there are no other claimants.”

“There are other claimants,” said Rufus Arden. “If I miss a drop of anything as good as this I’d deserve punishment.”

“And what about us women?” put in Polly. “Ladies first is my motto — first in everything.”

“There’s too much of this cursed feminism about,” said Rufus gloomily. “Take it, Polly. I don’t want to be nagged for a week. Besides, I know Mabel will make it up to me. Won’t you, Mabel?”

Mabel allowed as how there was plenty for all. She took one herself and drank it hastily. She felt she needed it after Dean’s refusal. When it was down, she began to recover, but her first glowing, anticipatory mood was dimmed, and with its dimming she looked a little coolly at Dean, thinking that anyone who could eat pork and soggy potatoes as he had eaten them the other night ought not to have any stomach at all. Also she became aware that his dinner clothes were a sloppy misfit, contrasting painfully with Rufus Arden’s and Edward Simms’ super-tailoring. She was glad when Pearlie announced dinner. Here, at least, she was sure of results. Dean Kennedy could not eat the dinner she had provided without experiencing such a revelation in taste as would make him into another man, gastronomically speaking. And more and more Mabel was realizing that she wanted him to be another man, and not himself.

In the little ceremony of seating her guests, her confidence returned more fully. Dean had had no chance to know good food, and he hadn’t money enough to buy good dinner clothes. He’d had a thin time, a bad break. She gave him a tender glance, marveling that all he’d been through hadn’t broken his spirit or altered his most undeniable good looks. With these to go on with, she could soon help him to all that he should have; she would supply the lacking elements of care and taste. It was her mission and her great joy.

As these ideas raced through her mind Pearlie began serving the first course, and a shout arose simultaneously from Cousin Rufus and Edward Simms.

“Blini!” they chorused. “Blini, blini, blini!”

They were the most perfect blini — little, melting, hot, thick pancakes, each proudly upholding a burden of fresh caviar and a high hat of sour cream! “What have I ever done to deserve this?” moaned Edward Simms as he took the first bite. “This is food for gods, not mere mortals.”

“I really should have had something lighter,” said Mabel, beaming, “but I know how you feel about caviar, Edward. . . . What’s the matter, Dean? Don’t you like them?”

Dean put on a conscientiously polite manner. “I’m sure they’re very nice, but somehow the flavor is so queer — ” He laid aside his fork. “I’ll just wait for the next course, if I may.”

“Good Lord!” snorted Rufus Arden. “Any man who can’t eat blini, and such blini — Ouch!” Polly had kicked him in the shin with strength and accuracy. He subsided. The blini of all the guests but Dean were eaten in an aching silence. At last Mrs. Tree had presence of mind to say soothingly, “Of course it’s an acquired taste,” but Rufus muttered, “Acquired me eye,” and gave Dean a hard and mean look; so Mrs. Tree’s tact was lost.

Pearlie now brought in the soup, a clear green turtle laced with dry sherry, a few morsels of the luscious, translucent flesh swimming languorously in the soothing tide. Tiniest, crisp, toasted sandwiches of highpowered cheese touched magically with cayenne and a drop of Worcestershire came with the soup, served piping hot from a covered dish. The dying conversation revived under this stimulus. Dean, Mabel was thankful to see, ate the most of his soup, and Cousin Rufus and Edward began to talk of the historic green turtle served at Birch’s in London, and to contrast it unfavorably with their present portion.

In this conversation. Dean took no part, for he was now chatting absorbedly with little Mrs. Tree on the subject of bookbinding; at least he was holding forth and she was listening as if, thought Mabel with annoyance, she was hearing nothing less than a divine revelation. Cara Mai’s name entered into Dean’s monologue and Mrs. Tree looked sweetly condolent. “Just who,” Mabel asked herself bitterly — “just who does Dean belong to, anyway?” She wondered if he himself knew.

After the soup came her chief dish, and she watched to see what effect that would have on him. The plumpest of milk-fed chickens had been carefully boned — Mabel had stood over the butcher and harangued him to do his best work — then stuffed with a bland, insidious mixture, mostly bread crumbs and sweet butter, with a mere whisper of herbs and a merer flicker of minced fried onion and minced broiled bacon; then the filled birds had been roasted to a rhapsody in browns, from palest beige to darkest gamboge; and being roasted, were served one to each person. Mango chutney chopped and jellied and cut into slices; sweet-potato pone bread in soft, flavorsome squares; and for piquancy and contrast, tiny fleurets of cauliflower steamed and masked in a sharply lemony hollandaise, were the good companions of the chicken.

“I was wondering what vegetable you’d have,” said Edward Simms. “This is absolutely right. And that sweet-potato pone’s a triumph.”

At least someone appreciated her efforts, thought Mabel. Dean said nothing. He did not touch his chutney after one taste, and he put more salt on the chicken. Mabel hoped that Pearlie did not see this treasonable act, for if it were reported to Savilla there would be lightning in the air. Rufus Arden and Polly were eating and exclaiming, and as for Edward, he redoubled his appreciation. But even when this course was finished and the salad was coming on, Dean still said nothing about the dinner.

Mabel always mixed her own salads at table. It was a rite. Pearlie brought in a tray with a bowl of snowy-white endive hearts and sprigs of emerald cress; another large bowl, empty, and a small one; crystal flasks of oil and vinegar, small open holders of various seasonings, and on a separate dish a crust of bread and a clove of garlic.

“The question is,” she said, indicating this last: “Shall we, or shan’t we? I put it to vote.”

“Aye,” said Rufus, Polly and Edward Simms instantly.

“Just as the others say. I dote on it,” offered little Mrs. Tree.

“What are you all talking about?” asked Dean Kennedy blankly. “I don’t get you.”

Mabel explained that they could have garlic in the salad or not, just as they desired. She began to pour measured oil and wine vinegar into the small bowl, and to add the salt and fresh-ground pepper and the grain of mustard, but her hand shook; it made her so nervous to have to point out the obvious.

“Salad?” asked Dean even more blankly. “Call that a salad?”

“Why, yes, Dean,” said Mabel, almost spilling the oil. “Of course it’s a salad.”

Dean smiled indulgently. “But, my dear girl, I — well, I don’t want to be rude, but I hardly call that stuff a salad.”

“What do you call a salad?” asked Edward Simms. “I’d be interested to hear.”

“My idea of a salad — the only kind of salad that’s worth eating — is a nice fruit salad — all kinds of fruit and nuts chopped up, you know, and a nice thick mayonnaise all over it.”

“But not for dinner!” gasped Mabel. “Surely not for dinner, Dean.”

“Certainly for dinner. Cara Mai and I used to have it almost every night because I’m so fond of it. She used to put every sort of fruit into it, and sometimes pieces of marshmallow, and then the mayonnaise — a lot — all over everything. Most delicious thing imaginable. I do wish you’d asked your cook to make one tonight, Mabel. It’s very simple, you know; just some nice canned or fresh fruit and a bottle of mayonnaise, and there you are. There’s nothing in the world I enjoy so much.”

A long silence followed this speech, at last broken by Edward Simms. “I think we might as well have the garlic,” he said gently.

“Yes, I think so too,” said Rufus. Both men avoided looking at Mabel, but their shock and horror dwelt upon their faces.

“You’ll really love it when you try it,” chirped Mrs. Tree to Dean.

Mabel said nothing. There was, she discovered, nothing to say. She rubbed the cut garlic lightly on the crust of bread and dropped it into the bowl with the endive and cress. Then she poured in the dressing and, taking her wooden fork and spoon, began lightly to lift and shift the salad with deft, delicate touch, so as not to bruise it, but to cover each leaf and stem with shining savory film, complementary to its chilled freshness and greenness. All the time she was doing it — and it was not a short process — something in her head was repeating over and over: “You cannot marry a man who eats fruit salad with mayonnaise every night for dinner. You cannot marry a man who eats fruit salad with mayonnaise every night for dinner. He is irreclaimable. He is lost. He is gone. Make up your mind to part with him forever, here and now. It is better so.”

Then, as Pearlie brought the cool plates, each already bearing a whorl of Virginia ham baked to meltingness, sliced paper-thin and cunningly curled to resemble a generous rosebud; then, as Mabel served the salad she heard her voice, as one far away, saying to Dean, “Do you care to try it, Dean, even if it isn’t” — she shuddered — “fruit salad with mayonnaise?”

No, he thought he wouldn’t. “It looks rather anemic to me,” he said jokingly. “Not the thing for a real man, all that grass. I don’t believe in trying strange foods, as a matter of fact. There’s too much attention given to food anyway; too much importance laid on it. A good plain meal, meat and potatoes and bread — ”

“And fruit salad,” said Edward Simms, “with mayonnaise. Don’t forget that.”

“Exactly — fruit salad with mayonnaise. There’s a meal that’s worthwhile. You can get it anywhere, any time. This business of fussing about with a lot of queer things, just to eat! It’s silly. It’s insignificant.”

“My dear Dean,” said Edward Simms, “a very wise and learned man — no less a person than the great Doctor Johnson — once said that human felicity is made up of many ingredients, each of which may be shown to be very insignificant. I count a dinner like this one a part of my felicity, and I heartily congratulate the exceptional taste which planned it and directed its preparation.”

“And I agree with you,” said Polly Arden. “I only wish I were as clever as Mabel.”

The last of the salad plates disappeared at this moment and the dessert was served. It was Savilla’s masterpiece, an evanescent apricot soufflé, light and hot as a July breeze, sweet as young love, filled with the essence of the most exquisite and subtle fruit that grows. Following it came a custard sauce, fluffed with whipped cream, strengthened cunningly with nothing less than old apricot brandy.

Edward Simms spoke with his mouth full; he could not wait: “Call this insignificant?” he said to Dean Kennedy. “Prefer fruit salad with mayonnaise to this, would you?”

“Oh, don’t scold him,” said Mabel. “Everyone knows what he likes best.” She said it almost gayly. She had made her decision. There was — she knew it now — a weight off her heart. She wasn’t going to marry Dean Kennedy. No, she definitely wasn’t going to marry Dean Kennedy. She couldn’t do it. The old romance had died a quick and permanent death; smothered, she thought merrily, suffocated and drowned, indeed, in fruit salad with mayonnaise for dinner. It had been on its way to perish before that. Reason had triumphed over sentimentality. The years since their youth had changed them too much; he wasn’t what she remembered or what she wanted except in externals. Perhaps, if she had started out with him long ago, in place of Cara Mai, there might have been adjustments, harmony; but it was too late. She couldn’t see herself any longer in the role of helper, comforter, inspiration and guide to — she looked at Dean, and chose the words deliberately — to a disgruntled, troublemaking, conceited man with an obstinate, confirmed lack of taste for the things she liked and knew about. Edward Simms was perfectly right; it was the small, livable tastes in common which made marriage possible. Edward Simms. . . . Edward Simms. . . . What about Edward Simms’ years of thoughtful devotion, his generous care, his watching out for her, his easy, amusing companionship? Why, Edward was the real romantic. And here he sat beside her, smiling at her over the soufflé, the same kind, tender, knowledgeable person he had always been. She felt her relieved heart go out to him yearningly as to her true mate.

“This is a great occasion, Mabel,” he said as he met her glance.

“You have no idea how true that is,” replied Mabel happily. “Now, shall we go in for coffee? It’s the kind you like, Edward. And, Dean, please take care of Mrs. Tree.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now