A Saturday Evening Post regular and writer of more than 100 short stories in the early twentieth century, Thomas Beer was best known for his biography of Stephen Crane as well as his novel The Mauve Decade. Beer’s fiction contained evocative metaphors and complex characters that preceded work along the same vein from writers like William Faulkner. In “The Mighty Man,” a big-city doctor returns to his Ohio hometown and the quirky citizenry that remains there.

Published on March 13, 1920

My father died in 1892 on the eve of my graduation from Princeton, and I did not see Zerbetta, Ohio, between his funeral and the spring of 1896, when a mixture of love and jaundice broke in on my dull progress as an interne at a New York hospital. I was ordered to rest and I could think of no better spot than Judge Lowe’s house in Poplar Street. Zerbetta would be more cheerful than my uncle’s home in Boston, where his daughters might be sympathetic about my halted courtship, for Miss Randall had flown to Europe with an aunt, and her shut windows blighted Park Avenue. So I went westward on the express, which happened to reach Zerbetta station ten minutes before time, an event so startling that people came rushing down Clarke Street, and the dogs that helped meet trains began to bark in chorus, their routine outraged. This swelled the audience of my arrival and while I was shaking hands with a dozen old friends someone commenced to whistle the Handel Largo in B Flat, Miss Randall’s favorite piano score. It seemed a noble addition to my welcome, though the whistler varied from the air considerably, and I looked about to find a pursed mouth among the many grins. It proved that he was a young fellow, even taller than myself, who leaned on the brick by the baggage room door and gazed gravely at the truck filling from the express car, a splash of April light on his bare head.

“Who’s that?” I asked Karl Gruber.

“Oh, that’s Walter McCurdy. You wouldn’t know him, though. He ain’t been here but three years. Nice boy.” He had the look of decency, and I envied his callous disdain of the cool day, but wished he would stop mangling the Largo by a series of breathy pauses and false notes.

“He’s a cousin or somethin’ of Bill McCurdy’s,” another lounger advised me; “but what d’you hear about ’em nominatin’ Major McKinley back East, Joe?”

Judge Lowe drove up to the curb behind the station just as the train drew out, and Walter McCurdy concluded his insult to Handel by smiling at my host. It was a charming fleet expression and I thought the judge must like him, as he gave a cordial nod and tapped the boy’s chest with his cane, going by.

“Come up to the house, sonny. I’ve got a new book for you. Well, Joe Henry, you look like an Egyptian mummy.”

We stood a second talking and the baggage master called to Walter that his box had come. I noticed the swing of his long legs as he wandered to the truck, but nothing prepared me for the ease of his sudden lift as he tilted the great wooden case on his shoulder and strolled away up Clarke Street, his sleeveless blue shirt dwindling between the glitter of the shop windows. Our carriage passed him as he turned into the cobbled yard of the McCurdy smithy, and I noted no flush on the pink of his neck.

“Oh,” said the judge, “poor Walter can throw anvils round like apples. I don’t suppose he knows he’s carrying that, and it’s probably full of pig iron. Fine-looking youngster, isn’t he? So your jaundice took the starch out of you, did it? Well, it’s about time you came home.”

Poplar Street had not changed beyond some felled trees here and there, and the maples were budding about the Presbyterian church, where my father had been pastor, duly honored, all through my boyhood. We went to service the next morning and I sat listening to the new preacher’s sermon, thinking reverently that my own parent had never been so tiresome and that the new preacher’s flat wife did not well become our former pew after my mother’s grace there; in fact, I got the full blow of sentimental repulsion to a difference. The fresh-stained glass threw blotches of gay tinting on the cream benches, guiltily carved on the backs with initials of my time. I missed known faces. Ethan Ross was in Cleveland. Eddie Lowe must be taking a Sunday rest from labor as a Princeton instructor. The altered choir sang wretchedly and when the Reverend Tillett announced that we must listen to another anthem I boiled. An anthem after the sermon was unheard of. I hoped the congregation would hiss indignantly, but the judge leaned to whisper that this was to show off Judy Patterson, and her father, the organist, set forth on a familiar prelude, so I stooped to put back my hat.

The choir got up from behind the red curtain and burst into a four-part version of the Largo, hashing the melody and bringing wild rage to my heart. Judith Patterson, I discovered, was singing soprano and presently was alone in the crime. I could not wish her death, for she had grown to be a pretty, vague likeness of Miss Randall, dark and slim, and she sang without flourishes in the strained tremulous fashion taught by dishonest masters who find a weak sweet voice and spoil it. Seeing her nervous I grew sorry and glanced about in the hope no one would smile. But the congregation sat courteously still, and soon the other choristers joined to complete the evil act. I shuddered, loyal to my love of the splendid rising music, and heard someone just back of us sniffle. It was the Sims pew, but the sniffler was Walter McCurdy, and I saw tears on his face as Judith Patterson missed a last C and the anthem ceased with a thunder from the organ.

“Yes,” said the judge, walking home across the street, “that was pretty awful. And I don’t know that it’s any compliment to turn Judy loose on Handel’s best tune, either. Did you see poor Walter crying? Well, I suppose he thinks Judy’s a new Patti — if he ever heard of Patti. This isn’t New York. We can’t go hear Jean de Reszke at the opera. My.Lord, it was ’eighty-one, last time I heard an opera! No, but I can’t say I think Boston’s done much for little Judy. What’s the use of trying to turn a wren into a nightingale, anyhow?”

“Has Judy been taking lessons, sir?”

“Lord, yes,” he chuckled. “Patterson sent her off to Boston last fall. She’s just back. Pity he ever sent her, I think. But he’s a jackass about her voice. Well, he’s spent three or four thousand on it. I wonder what heathen ever told him she could sing grand opera?”

I laughed, fancying Judy on the vast echoing stage of the Metropolitan, but the judge shook his fine white head, as always compassionate to human folly.

“No. Mort Patterson means to send the poor baby off next winter. He’s a little cracked, maybe. He’s been talking about it for two or three years. Why, what a cruel thing a man can be, Joe! It’s amazing how much a father’ll ask his children to do! He really thinks she’ll be a diva and some millionaire’ll marry her. He ought to be locked up.”

“What does Judy think?”

“Oh, the girl’s no fool. She’s got hard sense, but I’ll be blessed if I see what she can do but try to be a singer. He’s in debt up to his neck and I suppose she loves him. Mort’s not a bad man. He’s just a donkey. But what would Judy do in New York?”

I could not imagine an operatic director listening patiently to the feeble misled voice, and I began to be doubly sorry for Judith, remembered as a gentle quiet girl. She should have suitors, certainly, and I wondered if the big yellow-haired lad who had the kindness to weep over her singing would not step forward as a shield.

“She’d better marry someone,” I said, opening the judge’s gate.

“Not if her father knows it. This is what you doctors call an obsession, Joe. He thinks she’s got a career ahead of her. You’d better go tell him that New York isn’t any bed of down for an eighteen-year-old girl with a ten-cent voice. I tell you, the man’s cracked over it. He sees her hung with diamonds and pearls like what’s-her-name in that book. Trilby, isn’t it? What stuff folks write these days!”

“But I should think she’d find someone to marry — ”

“Oh,” the judge nodded, “that’s all right. Yes, she’s got a plenty of young men. She’s nearly as run after as Lorena Broome was in her time. But — well, her fool father’s got a mortgage on the store and — Come in, Walter.” He raised his cane to the great lad who was loitering along the fence, alone and plainly still uplifted by Judith’s share in the Largo. I smiled, for the boy was so unlike his relative, the rowdy blacksmith. He came up the veranda steps and the judge told him my name.

“You’re an inch taller than Joe, I guess. Well, that’s bigger than you’ve any right to be. Like Judy’s singing?”

Walter flushed and shuffled a sole on the planks, but made no answer for a minute while I held my face grave. Then he fumbled in his jacket and drew out a pad of paper with a dangling pencil, frowned, considering, and wrote, his tongue between his teeth, like a child.

“Well, I agree with you,” said the judge, crumpling the leaf, “and I wish her father hadn’t sent her away. A mighty nice girl, Walter. It’s a shame.”

Walter nodded, very red, and I ached with pity. We recoil from a bad vaccination mark on a woman’s smooth arm where a man’s worse scar would pass unnoticed. The boy was handsome enough to get the same effect, and dumbness to me is only less in horror than to be blind.

“Come on in,” the judge ordered, “and I’ll give you this book. It’s history and I know you like that, but for Lord’s sake don’t let Bill McCurdy drop it in the forge or the trough or somewhere.”

Walter grinned and followed the old scholar into the house. Quite shamelessly I picked up the fallen paper and read his round scrawl: “I think she has had her singing spoiled.” Then he had the honesty to weep for the spoiling, and he must be deep in love. At twenty-five I had not published Simplified Psychoanalysis and so filled my antechamber with neurotic people wanting to have their poor motives pried apart. I could like anyone, and Judy was a faint type of my idol. A flood of sympathy washed into my mind and I hoped Walter would marry his sweetheart. It was not professional, of course, but eugenics was still a hazy set of theories, and his marred splendor hurt me, as it did the judge, I found, over the lunch table.

“He wasn’t born dumb and Doctor Case thinks something could be done for him. Walter’s twenty. Now, let’s see. He’s from some place in Indiana and his mother was a cousin of McCurdy’s — no, his father. Let me get it straight. Well, his dad was away from home and the boy was sleeping in some kind of attic — the top of the house, anyhow — and the place took fire in the night, so his mother lost her head and didn’t think of him until after she’d run for help, All this time the poor pup was trying to get down out of his attic and not getting very far. He was nine. The fire burned the stairs and he jumped down into a tree. Hasn’t spoken since. He’s all right every other way. His folks are dead. He works down at the forge. It’s a pity something can’t be done. I wonder if he’d go back to New York with you?”

I had made some studies of aphonia at medical school and we discussed the matter while I damaged my liver with the judge’s sherry. But people came calling and it was close to Monday noon when I walked down Poplar Street to the drowsy square for a chat with Peter Vanois at the bakery, where the rolls in the showcase had the immutable seeming of marble and Mrs. Vanois was still humming some Gascon song to herself while she knitted garments for Peter’s baby.

“What d’you think of Judy Patterson?” Peter inquired.

I delayed an answer until I saw Mrs. Vanois smile civilly aside, then laughed, and Peter assented.

“Of course, everybody’s mighty fond of Judy. She’s a nice sort of girl, but — well!”

“It is very ‘orreeble,” said his mother. The Bordeaux street singers, she went on, were not more offensive to her ear, and she thanked God that Judy’s efforts would be restricted to a Protestant area. But as a friend of the family one could say nothing.

“And old Patterson’s mortgaged the store and everything he’s got to send her to Boston. Better go buy a pot of paint, Joe, and help him out,” Peter suggested. “Patterson’s got it all thought out. She’ll sing in the Presbyterian choir all summer, then she’ll go to New York, and then — he thinks — it’ll be ‘bout a week when she comes back in a private car with rubies for tail lights. He thinks she’ll bust right into the Metropolitan Opera and raise the roof.”

“I can hear the chandeliers falling,” murmured Mrs. Vanois, “and I see Madame Eames, who tears out her hair with envy.”

“That’s all right, mamma,” Peter drawled in the tongue of Zerbetta. “Who was it wanted me to be a sculptor ’cause I made horses out of pie dough, huh?”

Mrs. Vanois admitted that all parents were fools. However, Morton Patterson was of a stupidity unexampled even among the accursed Germans. Her French went too fast for me and I sauntered on down Clarke Street, passing shops where few signs were changed since I trotted errands for my mother. Morton Patterson’s Paint and Oils Store was changed, if at all, for the worse. I thought an expenditure of a gallon on his own brick would come well in place. The family must still live in the rooms above the gilt signboard, for a geranium box was being watered on a sill and I heard Judith singing tenderly, in the voice of her old solos when a children’s party needed that distraction. She was singing Eileen Aroon, and its soft sentiment dripped pleasantly down on me with drops from the geranium. I conjured up Miss Randall, happily unaware that she was just then having measles in London, and entered the shop ready to argue Morton Patterson limp.

He sprang from a chair in the rear and hobbled eagerly forward, not, as I fancied, to shake hands but to wait on me, for he did not know me at once and I saw a hopeful glow sink in his eyes as I told him I was Joe Henry. Still he seemed glad to see me and began to talk of New York with an instant direction. Did I go to the opera? Was it hard for a girl with good letters of introduction to have her voice heard? Letters from a celebrated Boston master? My desire to laugh gave way before his silly pride, and I stood lying until Judith’s skirt fluttered on the stairs and she came to meet me, genially declaring I had winked at her in church. Nearby she was most unlike Miss Randall, but a pretty, fragile thing, and we settled to a comfortable talk of Boston. Patterson broke in proudly with small babblings about the teacher who had prophesied so much for her. Her mouth twitched at each phrase.

“Maybe Joe doesn’t care for music, daddy,” she said at last and made a skillful shift to Judge Lowe’s rheumatism. I lounged against a shelf of paint cans while we gossiped, and the time slid on without a single customer while Patterson dozed in his chair, a yesterday’s Cincinnati Enquirer spread on his knees and his loose lips smiling. But he jumped as the door banged. Walter McCurdy nodded to me and blushed for Judith so that I warmed fraternally, wondering how he managed a courtship on these terms. The sunny window made his head romantic and I envied the fair curls as he reached down a jar of some oil from a shelf and found a quarter in the pocket of his leather apron.

“Well, Walter,” said Patterson rather stiffly, “I saw you in church.”

“And I hope you’re not being worked to death,” the girl smiled. “It’s a shame that horse bit Mr. McCurdy.”

He grinned, foolishly flexing his naked biceps, and the ancient staled ballad hopped into my mouth. The smith, a mighty man was he. The muscles of his brawny arms were strong as iron bands. I doubted that Walter could be worked to death, though the McCurdy smithy was the only one in town, since Bill McCurdy always bought off rivals or, given the backing of a little liquor, drove them out with blows. I hoped the boy was a milder character. He did not stay to be admired, and the sun made his bare shoulders gleam as he strode off down the plank sidewalk, balancing the heavy jar on a palm.

“He oughtn’t go round like that,” Patterson commented sourly, “in an apron and pants. It isn’t refined.”

“He’s mighty handsome,” I said, “and I’ll bet he could break rocks on his chest. It’s a shame he’s dumb.”

Patterson thought that Walter would have very little to say for himself if he could talk. And anyhow he wasn’t anything but a blacksmith’s helper. Wasn’t it true that lots of grand-opera stars married dukes and so on?

“Oh, daddy,” Judith said with a faint wail in her voice, “don’t be so silly!”

“Well, now,” he beamed, “it’s all right being modest, Judy, but let’s ask Joe if you haven’t got as good a soprano as any — ”

“Joe never was any sort of a liar, daddy. You don’t have to answer, Joe,” she cried.

“But didn’t Professor Rothschild write me that — ”

I gulped thankfully as some farmer came stamping in for a paintbrush, and I hurried down the street, glad that Judith had no delusions. McCurdy bellowed to me from a bench under the spreading horse-chestnut tree in the smithy yard and I crossed over the narrow roadway while he made jovial observations on my urban dress in tones that brought all the blood into my yellow skin.

“One those old mares of Sherm Potter’s took a piece out my leg,” he grunted, patting his bandages. “Want to look at it? No, I guess you see ’nough sore legs at your hospital. Well, how’s it feel to be back home, huh? Want a job? Walt’s got about all he can handle right now. You was in Patterson’s. I seen you comin’ out. Did that skinny old ape make any cracks at Walt? It’s come to a fine show when Mort Patterson’s lookin’ for a millionaire to marry Judy!”

I sat beside him and asked about the boy, who was noisy inside the dull smithy and just visible, his white skin rosy from the forge when the bellows roared. A dozen horses were waiting and the yard was full of drawling farm hands. A weedy apprentice scuttled between the forge and the cooling trough, and old Sherman Cody, the county bore, whined about a broken axle:

“Oh, Walt writes when he’s just got to tell me somethin’. We get along first-rate, seein’ I love him a heap an’ that makes it pretty easy to get what he wants to say. A mighty contented kind of feller too. Likes workin’. He don’t have to. His pa left him plenty. But, Lord, this old fool Patterson gettin’ high an’ mighty at his age! Walt could buy his whole stock an’ not feel it. An’ Patterson’s turned Demmycrat. Says he won’t vote for McKinley if he’s nominated, an’ him born an’ raised right in Ohio! An’ havin’ his stock insured! Say, Joe Henry, did you ever hear of anybody bustin’ into a paint shop and stealin’ a bucket of paint? I mind hearin’ of a drunk tramp that broke into a undertaker’s place once over in Crawford County and stole some silver plates for coffins, but what the hell could you steal in a paint store?”

“Well,” I said, “I don’t think Judy’s awfully high and mighty about Walter.”

The smith took another inch of tobacco from his slab with a vicious bite and helped it with a swallow from his usual quart bottle. His red-laced eyes rolled less savagely.

“Judy’s no fool. Walt ain’t asked her. Come to that, if she ain’t willin’ to marry the boy there’d be some sense to it. He just can’t talk. Make it kind of slow round the house. I ain’t a thing to say against Judy. But her pa’s got me itchin’ like the ringworm. What comes of playin’ the organ, I guess. Always was kind of soft in the head since his wife died off. An’ he’s got a mortgage at the First National for five thousand dollars an’ the whole town knows it an’ he ain’t makin’ enough to feed him an’ his girls sour milk on Sunday. Owes bills all over kingdom come, the — Hey!”

A yell cut his tirade and I ducked as a horse screamed. Something had annoyed a huge roan brute from the Ross stud, and the yard seethed as his halter snapped short. I saw the stallion rearing among the loungers by the door. Sumner Ross shouted to keep back. There was a smash of hoofs on a wagon bottom, then some runner bowled me over on the cobbles and my chin struck an unkind projection. A dance of prismatic moons filled my eyes. When I sat up, expecting a hoof on my skull, Walter was astride the crazy beast, his apron flapping like a brown leather guidon and his arms tense as he held something down in the stallion’s mouth. Froth covered his hands and I could not see what he used as a bit, for his mount plunged and the sun playing on the boy’s convulsed shoulders fascinated my dizziness. It was like a statue come to mad living.

“Bust his jaw, Walt!” McCurdy shouted, tottering on the bench. “Go on, smash his jaw off’n him!”

The stallion settled as if he heard the threat, and his head sagged. Someone stole warily up with a headstall and Walter drew the steel bar out of the bleeding mouth. Peace entered my heart. The muscles of his brawny arms were strong as iron bands, and I had seen it proved. A committee of farmers took charge of the Ross property and Walter walked back into the shadow of the smithy.

“Now,” said McCurdy, offering me the flask, “I’d call that a mighty useful kind of citizen. But Mort Patterson don’t think so — the ringtail baboon! By hell, I’d like to burn his store down!”

Rumor enlivened Clarke Street. I found Judith outside the shop, her hands twisted together, so stopped to tell the story.

“Oh, I wish I’d seen it! No, I don’t either. But Walter’s very brave, Joe. He pulled one of the Gruber boys out of the river last winter and the ice was so thin! It kept breaking. Oh, isn’t there some way you can cure dumb people, Joe?” I restrained a laugh. It was the most candid confession I have ever seen, and it touched me so that my eyes dampened.

“Look here — I’m going to see Doctor Case about it. Suppose Walter did get cured? Would you go to New York?”

“I don’t know what I can do! And they won’t insure the store again because it’s such an old thing and — Oh, people don’t seem to want paint! And daddy doesn’t like Walt because he can’t — can’t — ”

Clarke Street was at noon dinner. I stood with her head on my shoulder and she wept, while I worried. Common sense assured me that it was not an extraordinary match for the pretty girl. Morton Patterson had always thought well of his state as the town authority on music and a man of good family on the local scale, which meant prosperous respectability.

He might reasonably object to Bill McCurdy as a relative. The blacksmith was a chronic scandal and a subject for reform to all new clergymen.

“If I get Judge Lowe to talk to your father — ”

“But there’s the mortgage, Joe! Oh, I wish I’d never sung a note! I’m not a great soprano. I don’t think even Walter thinks I can sing very well, and he — You see,” she informed me as if it must be a surprise, “Walter’s in love with me.” The robins chirped in the maples and the sun made her lashes glisten.

“I’d guessed that,” I said, “and I don’t blame him much. Would you marry him, right now?”

“I — it isn’t his being dumb, Joe. But — oh, we haven’t any money and daddy mortgaged the store for me. Yes, I’d marry Walter, but — ” She struggled with obedience and sobbed woefully. “Daddy’s so proud of my voice and he doesn’t know — and he thinks I’m beautiful. And of course I’m not. My mouth’s too big and I always have freckles in summer. I wish I was dead!”

Doctor Case was a physician too lazy for ambition, but if there is waste in a profession vowed to benevolence he was wasted in Zerbetta. He would be called a psychiatrist today, and in 1896 his eye for nervous trouble would have made him a specialist elsewhere. He smiled angrily when I began to talk of Walter.

“Some of these days a Frenchman or a German will make a big splash in the frog pond with a book on suggestions in childhood. Take a look at the boy’s larynx and tell me what you think. Of course, he could talk! He was scared dumb. It’s a prolonged temporary paralysis — if that’s anything. He simply can’t bring himself to talk, and I suppose his fool of a mother saved him the trouble of trying. Read Trilby? Sure, everyone has. Well, a hypnotist could make Walter talk. It’s nothing but an inhibition. Gad, I wish we could give the human mind a pill! He’s no more dumb than you are! I wish you could transfer the thing to Judy Patterson! If I have to hear that squall again anyone that wants the best practice in this town _ can darned well have it!”

“You will if you go to Mrs. Reid’s party Thursday.” said the judge, “Judy’ll sing there, of course. But look here, Case — you say the boy can talk. Well, he must be wanting to mighty bad. Why doesn’t he?”

Doctor Case rubbed his bald spot and we argued. His point was that a lax fiber of the boy’s will was at fault.

“You’ve heard of the Christian Science cures where some bedridden person who hasn’t set foot to ground for years gets up and prances down the street? Well, that’s faith operating on will. Now, back when this happened to Walter if there’d been some sensible man round who could have forced the kid to talk — hypnotism or faith or any old way — it would have been all right. But he tells me his mother gave him a slate and let him write. He’s lost the habit of talking. There’s a center somewhere in his brain that forbids him to try even. I think if some — some crisis came up when he had to talk or be shot, he could. But all he has to do is to sit and make eyes at Judy, and it doesn’t call for words. That’s the trouble with being handsome. If I ever wanted to make love to a girl — well, I’d have to be mighty eloquent. But you go take a look at his larynx, Joe.”

I borrowed the mirror and instruments I needed and walked down to the smithy after dinner that night. Judy was practicing to her father’s accompaniment on a word piano. She sang the Gounod setting of the serenade in Mary Tudor, and her trills were causing sorrow in Zogbaum’s saloon opposite the paint shop. Fred Orn, the drunken mason, was audibly threatening to have someone lynched, and a knot of men on Zogbaum’s threshold stared up wearily at the lighted windows.

“A feller can’t get any rest anymore,” said Orn, “and I got a cat can sing better’n that. Honest, Joe, there’d oughta be some way of ampytatin’ a voice like that!”

Bill McCurdy was entertaining in the smithy by the glare of several lanterns slung to the black rafters. His friends, canine, female and male, were all affected by the April weather and had taken to song, about the beer keg. It was a wonderful racket. But Walter did not appear and McCurdy told me the boy was in bed upstairs.

“Seein’ he’s tamed one horse and put shoes on about fifty an’ mended ten wagons, he’s likely to be asleep. What you luggin’ all that junk for?”

“I want to have a look at his larynx,” I explained.

“Larynx? He ain’t got any that I know of. What kind of sickness is that? Say, I went over to Patterson’s an’ told him I’d pay his mortgage an’ all if he’d let Judy marry the boy. Say, that little fishin’ worm’s got more spirit’n I thought. He heaved a oil can at me. Look at my nose, will you?”

It seemed more inflamed than usual. I climbed the ladder to the second floor of the bachelor dwelling and found Walter asleep in a makeshift bed, looking like a gigantic cherub in a tattered nightshirt with his arms locked under his head. A shadeless lamp gave his hair the proper halo and he must be tired, I thought, if the gayety below permitted slumber. But curiosity and an honest wish to help kept me from crawling downstairs, and I stood admiring him while the party about the keg chanted a profane arrangement of There is a Happy Land. Perhaps it broke through his grave dream, for he frowned and his head rolled on the pillow vexedly. Then as I smiled his lips moved, and suddenly he spoke in a soft hoarse mutter.

“Oh, shut up!” said the dumb man.

It was quite distinct, though his throat swelled in the effort, and my blood stopped for an instant. Then I leaned down and shook him wide awake.

“Go on!” I begged. “Go on talking! Don’t you know you were talking?”

Walter peered up at me, frightened and pale, but shook his head. He reached for his pad and wrote a denial. “I was dreaming about talking.” He often dreamed of it, he wrote. In his sleep he could talk easily and could sing.

“Walter,” I insisted, “you did speak. I heard you. Try it again. If you can whistle you can talk. Try.”

But we wasted time. Something stopped him.

“I cannot make the cords in my throat work,” his statement ran. “Have you heard about what happened to me? When I saw the fire getting up the steps to where I was I tried to yell and I could not. And I have been that way all the time ever since.” He grinned and added, “Anyhow I used to stutter.” The larynx was not malformed or diseased as far as I could see in the faulty light. Walter accepted a cigarette and sat doubling his arms thoughtfully. At last he made an offer. “If you can find someone to cure me I will give him all the money I have. Is there someone in New York?”

“Oh, you can cure yourself,” I said, tossing my cigarette toward the fireplace and missing it, “but you’d better come back to New York with me.”

He nodded, then swung out of bed and went to stamp on the cigarette spark by the hearth, where some rags of paper were ready to catch.

“I am very scared of fire,” he wrote when I apologized. “It is the only thing I dream about. I mean nightmares and so on.”

He dreamed of fire rising toward him, of course, and of trying to scream for help. It was a natural recurrent terror. It amused him, awake. “Lord knows this place would go up like a haystack if Bill ever upset a lamp. I never saw anybody get as drunk as he does and not see snakes. He has had three quarts of red-eye since morning.”

I laughed over McCurdy’s derelictions and went away. Judy had stopped tormenting Clarke Street. The shades of the paint shop were pulled down and the glass caught the moonlight. But Zogbaum’s saloon was active and I halted there for a mild drink, finding gossip centered on Bill McCurdy’s affray with Mort Patterson, which was not at all imaginary.

“Huh,” said Peter Vanois, “I wish Patterson would get over this pipe dream about Judy makin’ a fortune. She ain’t likely to catch a better husband than Walt, anyhow, and Patterson owes me a good plenty. I don’t know what his mortgage is, but that buildin’ ain’t worth thirty cents. It’s likely to fall down any day.” Zerbetta was largely of the opinion that Judy might as well marry Walter. She had refused other young men of more standing, it was true, though I could perfectly understand her dislike of Columbus Sims, who remained the town bully in spite of his amiable family. Some old ladies regarded Walter as not quite nice enough for the girl, which was the plain result of his lodging with Bill. I think they were maternally worried. A handsome giant who has blue eyes and yellow hair is not safe from virginal scrutiny. Peter Vanois said that he could pick out fifty wives for Walter.

“Oh, yes,” said the judge, “Pete’s right. A lot of girls tell me they think The Village Blacksmith is a mighty fine poem. I was down at the yard one day last summer getting a lock fixed and it was funny how many girls had driven the horse in to get new shoes — or something. Well, I hear Mort Patterson’s forbidden Walt to come inside the store now. Family pride,” he mused, “is a queer study, Joe. The little jackass really thinks Walt isn’t good enough for Judy. It seems to me a dumb husband with money in the bank isn’t a bad bargain. He couldn’t talk politics at breakfast. Any danger of the children being dumb?”

“But the boy isn’t dumb, sir,” I exclaimed. “I heard him speak. He can if he’ll try. I’m sure Doctor Case is right. A hypnotist could make him talk. I think any sudden emotion or a shock might make him talk. I’d like to see what would happen if he took hold of a live wire or sat down on a red-hot horseshoe. And his cousin says the boy’s mother petted him after this fire instead of trying to get him cured. He can talk. It’s not congenital.”

“I hate medical words,” the judge observed, preening his white beard. “Well, I’m going down to have an argument with Mort Patterson. It’s a shame if he sends Judy off to break her heart trying to be a grand-opera star. She’d better twinkle here. I don’t like going in the store. The turpentine gets up my nose and I’m always afraid the floor’ll fall through.. Charlie Reid must have been crazy to write a mortgage. Five thousand on that rattletrap!”

His argument with Patterson was not a success. I think the proud father felt that Judy’s voice was not rousing Zerbetta to a frenzy of delight, and Walter was not tactful. Being forbidden the shop he spent odd half-hours sitting on the step of Zogbaum’s saloon and whistling all the girl’s best songs in his miserable manner. Clarke Street enjoyed the comedy and people came down to see Walter, with encouragement. Patterson raged idly. Judy was frankly touched by her lover’s attitude and for three days sang gently at night the simple airs her battered voice could compass, while Walter tramped up and down the roadway smoking.

It was natural that he was not asked to Mrs. Charles H. Reid’s Thursday evening party. The wife of the First National Bank had an easy rule for the selection of guests. She never invited people who were not known to have evening dress suitable to the Reid magnificence, and the gathering in the West Avenue house was as starched and laced as possible. We circulated drearily under the electric lamps and drank lemonade until supper.

“This,” said the judge, “is something Dante didn’t know about or he’d have made a new punishment in hell for it. Still there’s going to be champagne when we’re fed, and everyone looks mighty well for a small town. Good looks aren’t the private property of the aristocrat, Joe. Ever noticed it? Columbus Sims seems to be pretty drunk, by the way.”

Columbus was not sober. Some of the young men had braced themselves to this polite ordeal, and Columbus had overdone the thing. He was laughing loudly at intervals, and Mrs. Reid seemed worried as she moved from condescension to condescension about the parlors. Sumner and Winfield Scott Ross tried to keep him quiet from time to time, but he was aggravating and champagne did not calm him down. It was excellent champagne, for Mr. Reid had traveled habits and it pleased him to display his income from the bank and the new machinery plant.

Zerbetta, as represented, grew quite gay, and on the breath of merriment someone asked Judy to sing. She was not willing, but Patterson leaped at the chance and scurried to the piano. I saw Doctor Case make a gesture of grief and several persons drifted into the hall at once, but the judge and I were pinioned in a group near the white-stone fireplace and could not fly. Judy plucked desperately at the plump sleeves of her green frock and bade her father play Robin Adair. She got through the business nicely. People nodded a genuine pleasure and applauded too much, for Patterson swung on the stool and announced she would sing the Jewel Song from Faust.

“Oh,” said the judge, “a man ought to be hung for that!”

I think he wanted to intervene. I know I began to sweat for sheer pity as Judy opened her mouth. Zerbetta was not a musical center, but these moneyed farmers and lawyers knew well enough that Judy’s agitated wavering was bad from the first bar to the last. Even her obsessed parent realized, I am sure, that the silent men and women were suffering, for he glanced up now and then anxiously. I saw Doctor Case wriggle behind the large black silk dignity of Mrs. Edgar Ross, and young Sumner Ross hid a grin with a split white glove. The final trill shook me to a mutter of profane syllables, and just then Columbus Sims broke into wild laughter. He was always a boor. The judge started applause that covered the cruelty, too late. Patterson crouched on the stool, his face gray, and Judy shivered, bowing. Everyone stirred and the groups changed. I went off to smoke in the library, where a delegation of Bosses were telling Sims what they thought of him, on behalf of the county.

“But that may help Patterson out of his hobby,” Doctor Case whispered, “and if it does there’s something gained. Nasty to see, though. The girl’s as brave as an Indian. There’s Pete Vanois looking for you.”

Judy wanted me to take her home. Her father was ranging the parlors lapping up every crumb of flattery that local kindness could spill for him, but the girl wished to escape before dancing started, without taking her younger sister away from the party.

“And I don’t blame Colly Sims a bit!” she exploded as we slipped down the walk to the florid gates on West Avenue. “No. It was dreadful. I can’t sing that kind of thing. I suppose Madame Eames can, but I know I’m not Madame Eames. Oh, I hope daddy won’t — Oh!”

Walter was standing in the gateway, whistling the Largo, and she went to him without a word, for comfort.

“But,” she gulped when she had told her story, “I’m so glad you weren’t there, Walt. You might have done something to Colly, and that would have been dreadful.”

We walked slowly down into the square, where Walter took his arm away from her waist, and entered Clarke Street. Zogbaum’s was gay and Bill McCurdy led the chorus of a lay about honest labor and the old village blacksmith shop. His roar blew jovially over as I unlocked the paint-shop door. A smell of oil stole into the April air.

“I’ll have to leave the key in the lock for daddy and May,” said Judy. “Oh, Walt, do make Mr. McCurdy apologize to daddy! This is all so silly. And you shouldn’t have stayed up so late after working all day. Joe, do make him go to bed.”

I promised this, and held a match while she crossed the shop floor to the stairs, which creaked under her petty weight. We went on down to the smithy and the boy found a bottle of ale in the cooling trough, so we sat on his bed and consumed it, carrying on our pieced-out talk of the disaster.

“I was on the porch,” he confessed, “and I know it was pretty bad. I am going to have it out with Patterson tomorrow. I am kind of glad it happened because now he will not send her to New York, maybe. He is a fool if I know one. I have seen hens that have more sense.”

“But you wouldn’t mind having him for a father-in-law?” I laughed, and he shook his head, yawning, though he would not let me go.

I stayed talking and soon Bill McCurdy wabbled up the ladder. His red face rose like a sun through the trap, and he bellowed inarticulately when he saw us.

“Well, Walt — you kin get your duds fixed up f’r the weddin’, son. I got it all fixed up, see? Ol’ Mort’ll be mighty glad to have anybody marry Jud’ tomorrow.”

He sat down on the floor and howled merrily. But the reason of his joy did not make itself clear. He gabbled something about the paint shop and a door, then rolled over and went to sleep, snoring directly.

“I hope he has not gone and talked to Judy,” Walter wrote.

“He doesn’t know she’s home,” I said. “He’s just drunk. Better put him to bed.” Walter picked his disgusting relative up and dropped him on the smith’s untidy cot, still snoring. He was really fond of his only kinsman, who treated him with all the kindness possible, of course, and undressed him carefully. A box of matches fell from one of the snorer’s pockets and rattled on the boards about the bed.

“What on earth does he carry matches for when he doesn’t smoke?” I asked.

Walter did not know, but we could not talk against this gurgle of noise and I climbed down the ladder as the boy pulled off his shirt. The dark street was empty, as Zogbaum closed his saloon at twelve, and I noticed light behind the paint shop shades. Evidently Patterson had come home, I thought, and walked past to the square, pondering. But at the edge of the still space a policeman stopped me.

“What’s all that light in Patterson’s, doctor? It looks — ”

I wheeled, staring back, and just at the moment the dim glow became sharp red. It could be nothing else than fire, we both knew at once, and we ran together, shouting, down the block. But the blaze rose faster than our feet pounded, and the matches in McCurdy’s coat meant something now. I did not doubt that he had fired the shop, thinking the family away, and a yell from some window startled me to the dreadfulness of Judy’s place. There was only one flight of stairs from the rooms above to the ground floor and the oils would catch at any second.

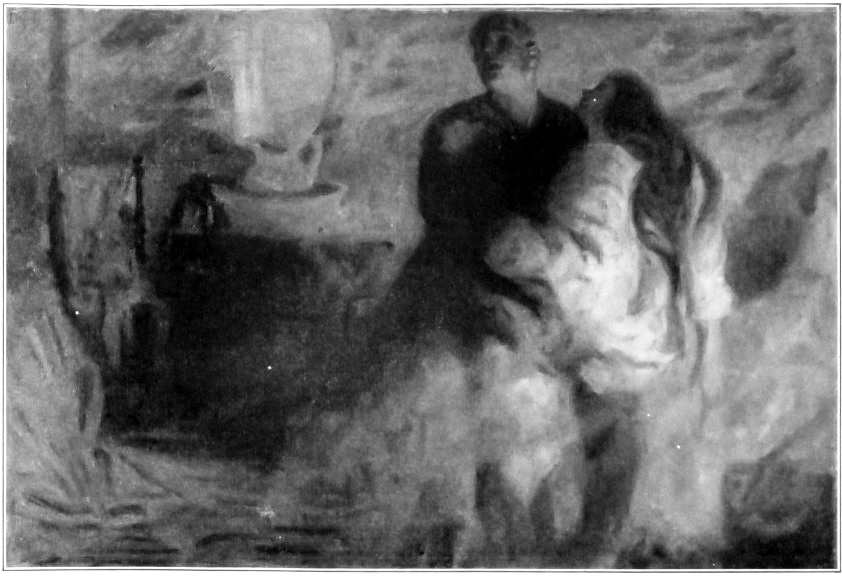

Voices rose as the street woke, but over any other sound came a hoarse shout of “Fire! Fire!” and I saw Walter racing up from the smithy, the flame bright on his breast and his teeth gleaming as he yelled. The miracle numbed me, then I rushed on and half-dressed people poured from the alleys. There was a small mob ready to drag him back from the door, where a rift of orange licked out beneath the panels. The paint shop was a furnace, dazzling and lovely to see, and the fury turned the struggling boy into a gold image. But no one could pass through the flame to the stair and he knew it. His face writhed in the effort to speak clearly. “Ladder!” he gasped. “Ladder!”

His eyes found the tilting sign above the doorway and he stood glaring up, then while the crowd edged back from the heat he stooped, his knees doubling, and shot from the sidewalk in a prodigious leap. The people screamed, but he got the top of the black-and-gilt board with one hand. His feet swung and smashed the show window so that a gush of fire swept about his trouser legs before he drew himself up to the sill above and knelt there, battering in the panes, then vanished.

“Gad, Joe!” howled Zogbaum in my ear. “That’s near fifteen feet.”

“Well,” I said idiotically,” he had to.”

They had found a ladder in some alley and we shoved it up, our hair crisping in the fierce belching from the shop. Walter walked down the rungs, with Judy wrapped in a pink quilt from her bed, held high in his arms. There began to be seen in the blinding orange explosive stars of color. The oil spattered out in flakes and the ladder dropped as the signboard caught. We were hypnotized by the beauty of the show and stood watching happily, now that the girl was safe. In fact, it was only when the engines were forced through the jam that I thought of the miracle again, and then because Doctor Case took my arm.

“Is it true he yelled?”

“Of course he did,” I said. “Great Scott! Where have they gone to? He hadn’t any shirt on and he must be cut up. Look round!”

A dozen men were hunting Walter, and Mrs. Vanois was ambling to and fro with a cloak of some sort for Judy. Her Gallic common sense suggested the smithy at last, and we hurried there, seeing a lantern alight by the forge as we crossed the yard and pushed through the wide door. It was very peaceful, after the street, though Bill McCurdy was snoring upstairs with the noise of stormy surf. Judy, still in her pink quilt, sat on an anvil, and Walter was grinning down at her, not aware that his naked chest and arms were scratched and bleeding or that his trousers were charred to the knee. She saw us and clapped her hands. “Oh, Joe, listen! Now do it again, Walt!”

“Judy,” said Walter slowly. “Judy.”

We applauded, quite as though this were the feat of some imported tenor instead of a muffled croak. Judy waved for silence.

“I — can — talk,” Walter stated.

“Oh, doesn’t he do it well?” said Judy proudly. “It’s just as plain!”

Then Mrs. Vanois had an attack of decent dismay, and took the girl away from him. The crowd surged in, some weeping, and the boy was patted on his back. Most of Zerbetta tried to congratulate him, and there was a muddle of men in soiled white waistcoats and all sorts of women who thronged the smithy, deserting the fire. Walter sat on the anvil and blushed and spoke in his queer awkward way, his eyes full of amazement, while Doctor Case and I made rough repairs on his surface. He has told me since that he did not know he was yelling until the need for a ladder arrived in his terror over Judy.

“Exactly,” said Doctor Case. “He had to talk, and he talked. All of you people get out of here. He’s got to go to bed.”

“Now, Walter,” said Judge Lowe, “Mr. Patterson’s coming, and I want you to be as pleasant as you can.”

Walter grinned, rubbing his jaw, but fell sober as the ruined man limped into the light. Patterson was not pleasant. Two shocks in succession had maddened him, and he did not know that Walter had saved Judy. He shook his fist and raved.

“You set fire to my place, Walter McCurdy, so’s I’d have to let Judy marry you! And I don’t care whether you can talk or not! It’s a dirty trick! And don’t you come soft-soaping round me to try —”

“Wait a minute,” the judge said sternly in his old official tone. “Wait a minute! Let the boy talk.”

Walter stretched his arms, strolling off to the ladder. He was too happy to quarrel. There is, in fact, no record that he has ever quarreled with anyone except an ill-advised schoolteacher who shut one of his small sons in a dark closet. However, he felt obliged to say something and turned at the ladder, thinking of a remark. I could see his throat ripple as he brought it out.

“You — talk — too — damn — much,” he said, and added: “Good night, daddy.”

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now