Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

For some, the Irish have a reputation for hostility and even violence. This reputation is largely undeserved. Consider, for example, that it was Irish farmers in the 19th century who, through their actions, gave our language the word for one of the most effective forms of peaceful protest: boycotting.

In the mid-1800s, Irish tenant farmers had few rights to the land they worked and were often expected to pay exorbitant (and growing) rents to their aristocratic landlords. The Irish National Land League was founded in 1878 to help secure better working conditions, fairer rents, and more property rights for poor farmers from wealthy landowners, and especially absentee ones.

A famine hit Ireland in 1879, taking a toll not only on farmers’ crops but on their ability to pay their rent. This famine wasn’t nearly as devastating as the Great Famine of 1845-1849 (called the Irish Potato Famine outside of the Emerald Isle), but the memory of that difficult time and the fear of its return haunted Ireland’s farmers.

Into these uncertain and quarrelsome times stepped a man named Charles Cunningham Boycott. In 1880, he was the land agent left in charge of the estate of John Crichton, Lord Erne, in Ireland’s County Mayo. When it came to collecting rents and keeping his tenants in order, Boycott wasn’t a lenient man, and in autumn of that year, he attempted to evict 11 tenants.

But the Irish National Land League wasn’t going to stand for it.

Boycott’s employees and tenants were urged — in some cases possibly forced — to isolate Boycott by withdrawing their labor. All business with Boycott was to stop, from the care of his stables to his laundry to the delivery of his post to, yes, the reaping of crops.

Boycott needed help, but he made a mistake in his choice of savior: He pleaded to the press. In a letter to The Times, he wrote, in part, “I can get no workmen to do anything, and my ruin is openly avowed as the object of the Land League.”

The story became international news. Newspapermen swarmed the county as troops were roused to protect volunteers from the north who stepped in to bring in the harvest, but the damage was done. According to Niall O’Dowd, founder of IrishCentral.com, “the episode cost at least £10,000 to harvest about £500 worth of crops.”

What’s more, the Irish National Land League established itself as a powerful grassroots force, the “Boycott treatment” was proven an effective nonviolent means of protest, and the word boycott entered the English language.

That boycott stems from the name of a particular man is not surprising — English contains many eponyms. What is surprising is how quickly the word caught on, spread, and became a common word in English. Less than half a year after the original boycott — on February 12, 1881 — Saturday Evening Post readers found this announcement in the News Notes column:

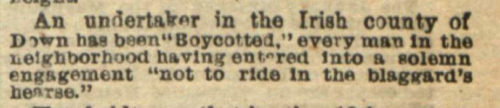

An undertaker in the Irish county of Down has been “Boycotted,” every man in the neighborhood having entered into a solemn engagement “not to ride in the blaggard’s hearse.”

The quotation marks and capitalization mark it as a new word, if not a new idea, for readers. But by just a year and a half later, the quotation marks had fallen away and the capitalization was dropped, and the word was used without any indication that readers might not understand its meaning. The following announcement appeared in the December 16, 1882, issue of the Post:

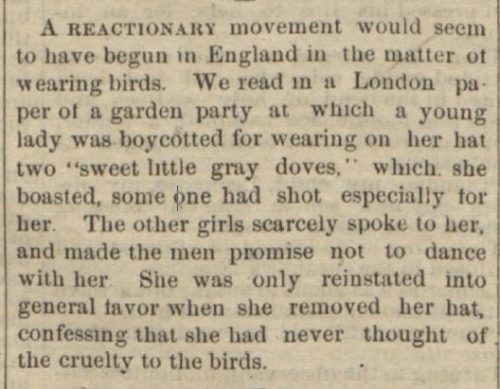

A REACTIONARY movement would seem to have begun in England in the matter of wearing birds. We read in a London paper of a garden party at which a young lady was boycotted for wearing on her hat two “sweet little gray doves,” which, she boasted, some one had shot especially for her. The other girls scarcely spoke to her, and made the men promise not to dance with her. She was only reinstated into general favor when she removed her hat, confessing that she had never thought of the cruelty to the birds.

And it didn’t spread only into English. The word found its way into German as der Boykott, French as le boycottage, and Italian as boicottare, to name but a few. Even more than St. Patrick’s Day, boycotting is an Irish legacy recognized the world over.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

And I thought a boy cot was something found in a scouts camp tent.