The Basics

The operating principle of American democracy is that government reflects the will of the people. Government officials are chosen from among the people by popular consent, and any citizen in good standing has the right to stand for election.

However, citizens cannot get themselves elected today without considerable funding to run a campaign. And there is typically a correlation between the amount of campaign money a candidate can draw on and their chances of winning an election.

Today, the cost of campaigns is sharply rising.

Most Americans feel that money has too much influence on elections.

They believe their will has little effect on laws and elections, which are determined more by the amount of money in politicians’ coffers.

They fear their legislators are elected for the money they can raise, not for their abilities.

And that, in turn, these wealthy office-holders are bound to give preferential treatment to the backers of their campaign.

Campaign finance laws are intended to ensure a degree of fairness between candidates, to prevent the better funded candidate from defeating a candidate who better represents the people. The seek to preserve the democratic nature of elections by ensuring that monied interests do not supersede public interests.

Our campaign finance laws are enforced by the Federal Election Commission (FEC), an independent agency that governs the financing of campaigns for the House, Senate, presidency and vice presidency.

The Controversies

- A 2010 Supreme Court Decision in Citizens United v. FEC removed restrictions on spending on campaign communications by corporations, unions, and organization. The majority opinion stated that outlawing all independent expenditures by corporations and union violated the right of free speech. The dissenting opinion argued “a democracy cannot function effectively when its constituent members believe laws are being bought and sold

- Critics complain that the FEC is ineffective, unwilling to enforce rules, protective of the status quo, and too slow to address campaign improprieties.

- Others claim that the enforcement of these laws infringes their right of free speech.

- Critics are also concerned that recent federal rulings have enabled corporations, or the owners of corporations, to engage directly in the electoral process. The fear is these organizations will use large amounts of capital to sway elections and laws to their corporate interests.

- Recent elections have raised concerns about the influence that million-dollar social media campaigns have had on election. Unfortunately, the Commission has been slow to address this new threat to democratic elections. It is uncertain how to regard, or even regulate, social-media-based campaigning.

The Law

Federal campaign finance law covers three broad areas:

- Public disclosure of funds raised and spent to influence federal elections.

- Restrictions on contributions and expenditures made to influence federal elections.

- The public financing of presidential campaigns.

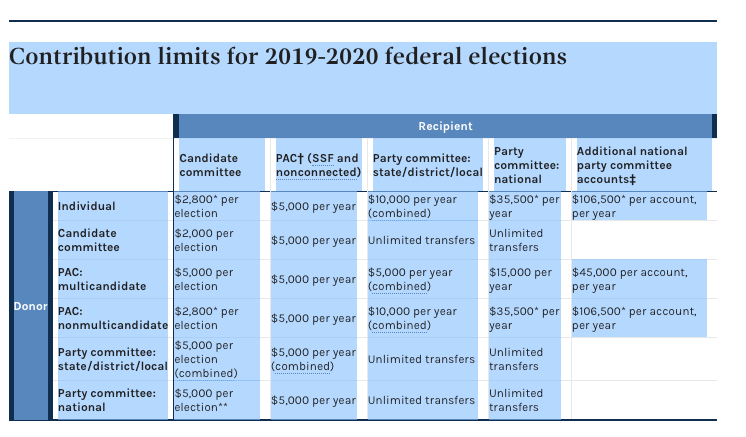

Listed below are several of the contribution limits enforced by the FEC.

*Indexed for inflation in odd-numbered years.

†“PAC” here refers to a committee that makes contributions to other federal political committees. Independent-expenditure-only political committees (sometimes called “Super PACs”) may accept unlimited contributions, including from corporations and labor organizations.

‡The limits in this column apply to a national party committee’s accounts for: (i) the presidential nominating convention; (ii) election recounts and contests and other legal proceedings; and (iii) national party headquarters buildings. A party’s national committee, Senate campaign committee and House campaign committee are each considered separate national party committees with separate limits. Only a national party committee, not the parties’ national congressional campaign committees, may have an account for the presidential nominating convention.

**Additionally, a national party committee and its Senatorial campaign committee may contribute up to $49,600 combined per campaign to each Senate candidate.

The Agency

The FEC enforces all laws governing the funding of elections, as spelled out in the amended Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA). It governs the raising and spending of campaign finances and specifies limits on contributions and expenditures.

As originally passed, the 1971 Act was principally concerned with increasing the disclosure of contributions for federal campaigns. It has been amended several times over the years.

Today, under the guidance of the Act, the FEC limits contributions and expenditures, investigates complaints, prosecutes violations, ensures all campaigns release their finance information, and oversees the public funding of presidential elections.

The FEC holds weekly public meetings to consider new regulations, issue opinions, and approve audit reports from presidential campaign committees. Enforcement actions and litigation are addressed in closed sessions. Investigations are launched by complaints, which can include any member of the public.

The commission publishes reports by campaign committees, which states how much each campaign has raised, and lists all donors over $200.

How We Got Here

As early as 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt recognized the need to eliminate the corruption within the electoral process. He called for legislation to ban corporate contributions for political purposes. It was the beginning of several congressional actions.

- 1907: The Tillman Act prevents corporations and national banks from contributing to election campaigns.

- 1910: The Federal Corrupt Practices Act is the first federal statute to combine multiple campaign finance provisions, with special attention to disclosure requirements.

- 1911: The previous law is amended; it now requires candidates to disclose their finances and sets spending limits.

- 1925: Another amendment expands the list of who must file quarterly disclosure reports. Also, spending limits on campaigns are raised.

- 1939: The Hatch Act asserts the right of Congress to regulate primary elections and also sets limits on contributions in congressional elections.

- 1947: The Taft-Hartley Act, among other things, extends the Tillman Act to include contributions from both corporations and labor unions, and applies this exclusion to primary elections campaigns.

- 1971: The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA) replaces existing federal campaign finance laws. It establishes more stringent disclosure requirements for federal candidates, political parties, and political action committees. It also lays out the legislative framework for separating different funds — political action committees, for example. Administrative responsibilities are divided between the Clerk of the House of Representatives, the Secretary of the Senate, and the Comptroller General of GAO.

- 1974: FECA is amended to limit contributions and spending, and to establish Federal Election Commission to assume the functions previously divided between agencies listed above.

- 1976: In Buckley v. Valeo, SCOTUS rules that, while individual contributions can be limited, other spending limits within campaigns are unconstitutional.

- 2002: The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (McCain-Feingold Act) prohibits national political parties, federal candidates, and officeholders from soliciting soft money contributions in federal elections. (Soft money refers to funds that are not contributed to a specific candidate, but rather to a party or committee.) The Act also prevents businesses and unions from using their treasury funds to finance electioneering communications, which are defined as “broadcast ads referring to clearly identified federal candidates within 60 days of a general election or 30 days of a primary election or caucus.”

- 2010: Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission rules this latter provision was unconstitutional. SCOTUS decides by a 5-4 vote that the First Amendment applies to corporations; thus the government cannot limit corporations’ political spending.

- 2014: Chief Justice John Roberts rules that biennial aggregate contribution limits are unconstitutional. They had previously limited donors to $123,000 in a two-year election cycle.

Presidential-campaign spending has increased over time but, when adjusted for inflation, population growth, and income growth, the rise in spending is less remarkable.

Glossary

Electioneering communications is any radio or TV ad that refers to a clearly identified federal candidate, and is distributed within 30 days of a primary or 60 days of a general election. They are not permitted to be coordinated with the candidates’ campaign, and corporations and labor unions are barred from using them.

Express advocacy ads clearly support or oppose a particular electoral outcome and are subject to federal campaign regulations (unlike issue advocacy ads).

Issue advocacy ads bring awareness to public issues. It does not support or attack any specific candidate. Since its purpose is to educate the public, it is regarded by the courts as free speech. Hence sponsors don’t have to publicaly disclose funding sources and there are no limits on contributions.

Communication costs are expenses that unions, trade groups, and other member organizations incur when they communicate with their members and stockholders. If those communications expressly advocate the election or defeat of a clearly identified federal candidate, the directly associated costs have to be reported to the Federal Election Commission.

Hard money is money given directly to a political candidate. The amounts and sources of hard money contributions are regulated by the Federal Election Commission.

Soft money is money given to a political party or political action committee. There is no limite on the amount, and it can come from any source, including corporations and unions, but it can’t advocate the election or defeat of a particular candidate.

Independent expenditures refer to communications concerning a particular candidate that come from outside the candidate’s election organization. It is not coordinated with the candidate’s campaign, an authorized candidate committee, or a political party. Generally, there is no limit placed on independent expenditures.

Political Action Committee (PAC) is an organization created to raise and spend money to defeat and election candidates. There are three kinds:

Separate Segregated Fund (SSF): These political committees — established and administered by corporations, labor unions, member organizations, or trade associations — only solicit contributions from individuals associated with sponsoring organizations.

Nonconnected committees aren’t connected to any other entity, and are free to solicit contributions from the general public.

Super PAC (also known as an independent expenditure-only committee) can raise and spend unlimited sums of money from corporations, unions, associations, and individuals to overtly advocate for or against political candidates. Unlike traditional PACs, super PACs are not allowed to donate money directly to a political candidate, and their spending can’t be coordinated with a candidate’s campaign. Super PACs must file regular reports with the Federal Election Commission.

Social Welfare Organization is a non-profit group —termed by the IRS as a 501(c) — that promotes social welfare, such as churches, charities, and educational institutions. Some types of 501(c) groups are allowed to participate in politics, but must spend less than half of their money on politics. Unlike Super PACS, these organizations are not required to disclose their donors.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now