Every headstone at Arlington tells a story. These are tales of heroes, I thought as I placed the toe of my combat boot against the white marble. I pulled a miniature American flag out of my assault pack and pushed it three inches into the ground at my heel.

I stepped aside to inspect it, making sure it met the standard that we had briefed to our troops: “vertical and perpendicular to the headstone.” Satisfied, I moved to the next headstone to keep up with my soldiers. Having started this row, I had to complete it.

One soldier per row was the rule; otherwise, different boot sizes might disrupt the perfect symmetry of the headstones and flags.

I planted flag after flag, as did the soldiers on the rows around me. Bending over to plant those flags brought me eye-level with the lettering on those marble stones. The stories continued with each one. Distinguished Service Cross. Silver Star. Bronze Star. Purple Heart. America’s wars marched by. Iraq. Afghanistan. Vietnam. Korea. World War II. World War I. Some soldiers died in very old age; others still were teenagers. Crosses, Stars of David, Crescents and Stars. Every religion, every race, every age, every region of America is represented in these fields of stone.

I came upon the grave site of a Medal of Honor recipient. I paused, came to attention, and saluted. The Medal of Honor is the nation’s highest decoration for battlefield valor. By military custom, all soldiers salute Medal of Honor recipients irrespective of their rank, in life and in death. We had reminded our soldiers of this courtesy; hundreds of grave sites would receive salutes that afternoon. I planted this hero’s flag and kept moving.

On some headstones sat a small memento: a rank or unit patch, a military coin, a seashell, sometimes just a penny or even a rock. Each was a sign that someone—maybe family or friends, perhaps even a battle buddy who lived because of his friend’s ultimate sacrifice—had visited, and honored, and mourned.

For those of us who had been downrange, the sight was equally comforting and jarring—a sign that we would be remembered in death, but also a reminder of just how close some of us had come to resting here ourselves. I left those mementos undisturbed.

After a while, my hand began to hurt from pushing on the pointed, gold tips of the flags. There had been no rain that week, so the ground was hard. I questioned my soldiers how they were moving so fast and seemingly pain-free. They asked if I was using a bottle cap, and I said no. Several shook their heads in disbelief; forgetting a bottle cap was apparently a mistake on par with forgetting one’s rifle or night-vision goggles on patrol in Iraq. Those kinds of little tricks and techniques were not briefed in the day’s written order, but rather get passed down from seasoned soldiers. These details often make the difference between mission success or failure in the Army, whether in combat or stateside. After some good-natured ribbing, a young private squared me away with a spare cap.

We finished up our last section and got word over the radio to go place flags in the Columbarium, where open-air buildings contained thousands of urns in niches. Walking down Arlington’s leafy avenues, we passed Section 60, where soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan were laid to rest if their families chose Arlington as their eternal home. Unlike in the sections we had just completed, several visitors and mourners were present. Some had settled in for a while on blankets or lawn chairs. Others walked among the headstones. Even from a respectful distance, we could see the sense of loss and grief on their faces.

Once we finished the Columbarium, “mission complete” came over the radio and we began the long walk up Arlington’s hills and back to Fort Myer. In just a few hours, we had placed a flag at every grave site in this sacred ground, more than two hundred thousand of them. From President John F. Kennedy to the Unknown Soldiers to the youngest privates from our oldest wars, every hero of Arlington had a few moments that day with a soldier who, in this simple act of remembrance, delivered a powerful message to the dead and the living alike: you are not forgotten.

The Thursday before Memorial Day is known as Flags In at Arlington National Cemetery. The soldiers who place the flags at every grave site in the cemetery belong to the 3rd United States Infantry Regiment, better known as The Old Guard. Since 1948, The Old Guard has served at Arlington as the Army’s official ceremonial unit and escort to the president.

I walked through Arlington for Flags In with The Old Guard in 2018. “What better way to show the nation and our fellow soldiers that we care and we never forget,” observed Colonel Jason Garkey, the regimental commander. As we walked along streets named for legends like Grant and Pershing, he added, “This mission is really important for The Old Guard, too. It’s the only day of the year when the whole regiment operates together. It gives all my soldiers—all my mechanics and medics and cooks—a chance to come perform our mission in the cemetery.”

Flags In carries a special meaning for our citizens, too, judging by our conversations that afternoon. Col. Garkey greeted every civilian who approached us. Most were curious about the soldiers they saw walking across the cemetery. As he explained Flags In and The Old Guard, without fail they expressed their fascination and gratitude. In Section 60, we encountered families and friends paying early Memorial Day visits to their loved ones. Col. Garkey thanked them for their sacrifice, and they thanked him for his service and for remembering their fallen heroes. He never mentioned that those were his soldiers or that he had planted flags that day at the graves of his own friends and mentors.

My turn at Flags In came in 2007 during my own tour at Arlington. I had joined The Old Guard a couple of months earlier, after serving a tour in Iraq with the 101st Airborne Division. My path to The Old Guard was unusual—like my journey into the Army itself.

It began the morning of 9/11 in a law-school classroom. In those days before smartphones, we did not learn that America was under attack until class ended, almost an hour after the first airplane hit the World Trade Center. But my life changed in that moment. I knew the life I had anticipated in the law was over.

I wanted to serve our country in uniform on the front lines. I finished school and worked for a couple of years to repay my student loans, time I also used to get prepared physically and mentally for the Army. It took my recruiter by surprise when I told him that I wanted to be an infantryman, not a JAG lawyer. To his credit, he signed me up and shipped me out, setting me on the path to Iraq. After more than a year in training, I joined the 101st in Baghdad in 2006, taking over a platoon of Screaming Eagles.

We conducted raids, laid in ambushes, dodged roadside bombs and sniper fire, and sorted out the dead in a vicious sectarian war. And at the end of that tour, to my surprise, the Army gave me orders to The Old Guard, even though I had not applied to the all-volunteer regiment. I knew The Old Guard was a special unit. The regiment has some of the highest eligibility standards in the entire military. Old Guard alumni were among the most squared-away soldiers I knew in the Army. And the mission set—not only conducting daily funerals in Arlington, but also world-famous ceremonies like presidential inaugurations and state funerals—called for the Army’s best soldiers, performing at the highest levels. I looked forward to the assignment and I felt honored while serving at Arlington.

But I did not fully appreciate our nation’s special reverence for The Old Guard and Arlington until years later, when I entered public life. A political newcomer, I spent the early months of my first campaign introducing myself to Arkansans, telling them about myself and what I hoped to accomplish for them. The most common question I got was not about Iraq or Afghanistan or about iconic Army institutions like Ranger School. No, the most common question, by far, was about my service with The Old Guard. The same holds true today; when I speak around the country to new audiences, questions about The Old Guard outnumber all the others. Likewise, thousands of Arkansans visit me each year in Washington. When I ask them about the highlight of their trip, Arlington tops the list.

The Old Guard embodies the meaning of words such as patriotism, duty, honor, and respect. These soldiers are the most prominent public face of our Army, perform the sacred last rites for our fallen heroes, and watch over them into eternity. The Old Guard represents to the public what is best in our military, which itself represents what is best in us as a nation.

As Old Guard soldiers, we viewed the funerals through their eyes as we trained, prepared our uniforms, and performed the rituals of Arlington. We held ourselves to the standard of perfection in sweltering heat, frigid cold, and driving rain. Every funeral was a no-fail, zero-defect mission, whether we honored a famous general in front of hundreds of mourners or a humble private at an unattended funeral.

Although funerals are The Old Guard’s highest-priority mission, the regiment also performs in ceremonies around the capital almost every day. From welcoming foreign leaders at the White House and the Pentagon to honoring retiring soldiers at Fort Myer, The Old Guard represents the discipline and skill of all soldiers. Among its ranks, The Old Guard boasts world-class musicians, the military’s most elite color guard, and the Army’s premier drill team. They carry the Army story and values to worldwide audiences and the smallest gatherings alike, always with pride and precision.

Arlington National Cemetery and The Old Guard transcend politics. We live in politically divided times, to be sure. Yet the military remains our nation’s most respected institution, and the fields of Arlington are one place where we can set aside our differences. Which itself is something of a historic irony, because our national cemetery was birthed in the most divisive time in our nation’s history, when Americans killed each other on such a mass scale that a farm across the river from our capital became the graveyard for those war dead. Perhaps because of those bloody origins, Arlington National Cemetery emerged from the ashes of the Civil War as a place dedicated to healing, reconciliation, and remembrance.

What the Old Guard does inside the gates of Arlington is a living testament to the noble truths and fierce courage that have built and sustained America. We go to great lengths to recover fallen comrades, we honor them in the most precise and exacting ceremonies, we set aside national holidays to remember and celebrate them. We do these things for them, but also for us, the living. Their stories of heroism, of sacrifice, of patriotism remind us of what is best in ourselves, and they teach our children what is best in America.

On the eve of the war that transformed this farm into a national cemetery, President Abraham Lincoln pleaded for unity in his First Inaugural. “Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection,” he acknowledged, while appealing to the “mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land.” In our days, as in his, passions can no doubt strain our bonds of affection, but those mystic chords of memory still stretch from the patriot graves of Arlington across our great land, calling forth yet again “the better angels of our nature.”

For the fallen and their families, The Old Guard honors their service and sacrifice. For us, the living, The Old Guard embodies our respect, our gratitude, our love for those who have borne the battles of a great nation—and those who will bear the burdens of tomorrow. No one summed up better what The Old Guard of Arlington means for our nation than did Sergeant Major of the Army Dan Dailey. He recalled a moment with a foreign military leader while driving through the cemetery to lay a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. “I was explaining what The Old Guard does and he was looking out the window at all those headstones. After a long pause, still looking at the headstones, he said, ‘Now I know why your soldiers fight so hard. You take better care of your dead than we do our living.’ ”

From the book “Sacred Duty: A Soldier’s Tour at Arlington National Cemetery” by Tom Cotton. Copyright © 2019 by Thomas B. Cotton. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

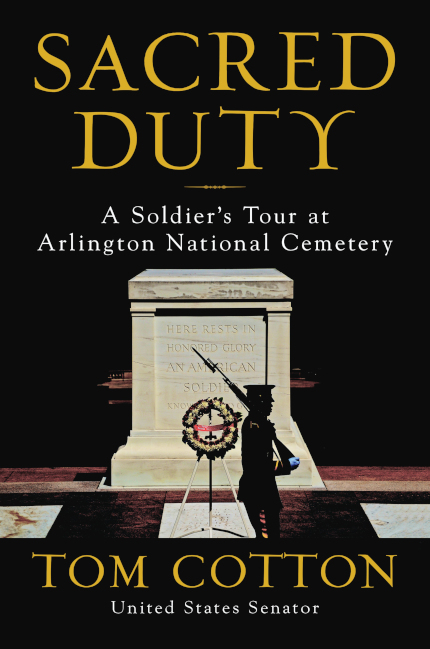

Featured image: U.S. Army.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I was with a group of Veterans on South Plains Honor Flight 17 in October 2017. My son was the “manpower” for my transport chair as we toured the Cemetery at Arlington. We were both touched, grateful to be Americans.

This is beautiful. My wife awaits me in Gerald Solomon National Cemetery Saratoga. PFC Elwood H. Hacker age 85.

My son is buried in Arlington, section 66. I am physically unable to travel from Florida too Washington as I have done for for many ;years in the past. Now I visit Arlington via the computer and web sites and remember with love and pride my son who I lost at just age 22. Thank you for sites like this. Mrs Susan Dennis Winters, mother of Sg Franklin Winters.

I want to thank all the people that do things for our National Cemetary. The Flags make it look so beautiful

and respected. Thank you to everyone that places the flags there, what a wonder ful job you have always

done. I remember helping lay a wreath there one year, years ago with some other woman and it was such a

great honor. Thank you

Thank you, Mr Cotton for the article about the Old Guard and Arlington National Cemetery. Being a Gold Star son, the article meant something very special. My father was killed on July 13, 1944 somewhere near Saint Lo, was initially buried at Sainte-Mère-Église, until 1948, when his remains were returned to Rock Valley Iowa. I was 10 at this time and I remember the troop train arrive on the Milwaukee Road train tracks, met by members of the local American Legion, my mother, my sister, other relatives, his buddy, and several other family members who had survived. I was so impressed by the honor guard, who protected my father and who was so kind to my mother. My mother died in 1995, a widow for almost 51 years. I was fortunate to visit Arlington in 2005 with my daughter and her family. My 7 year old grandson asked me “who owned all of this land?” I told him I was unsure. He knew the answer and that it was confiscated from Robert E. Lee.