William Fay was a short story writer for the Post in the mid-1900s. He specialized in stories about crime and the city, many of which he adapted for TV in the electronic era. His detailed descriptions of seedy city life in a tale of deception and violence couch some foreshadowing in this gritty serial. “I’ll Get Even” is a two-part story about a man who loses his wealth and the unlikely scenario that leads him back to the money.

Originally published on July 15, 1950

He drove his car into the tunnel from the Jersey side and came into Manhattan as a pilgrim might come to Mecca, Jerusalem or Rome. The streets of home, he thought, with all the magic they once held for him, and they led him uptown until “No Parking” signs defeated him. He was obliged then to turn about and leave the car in a parking lot near 23rd Street.

“Ya’ll be long, Mac?” the attendant asked.

“A few hours, maybe; till the shows are out.”

He took a nickel from his pocket and went into the subway and wondered was the nickel too fat or the coin slot just too small. It took a moment to remember having heard the five-cent fare had left New York and that the new machine was hungry for a dime. He didn’t mind the extra nickel, but he subconsciously resented any changes inflicted on New York City in the time he’d been away. He wanted all the sights and sounds and things that he was able to recall, including the five-cent fare, and even, if it could be redeemed, La Guardia’s nine-gallon hat. Because New York was what he had come back to see — and foolishly, perhaps, as though the city were an album of pictures whose pages, merely glimpsed again, could yield to him a measure of the good things he had lost.

He put a penny in a gum machine and looked at himself in the machine’s grimed mirror without marked pain or approval. An express rolled by on a center track; the express came heaving and bang clattering its way, so that the station trembled, if possible, and without his knowing it, his hand touched the glass frame of the photo with a kind of reverence. This was the magnet, stronger than the rest, that had drawn him back to town — to see her once, if only from the dark anonymity of a paid-for seat, and that, he reasoned in good conscience, was not too much to ask.

Back on Broadway he paid a speculator twenty dollars for a single seat to the show. He put the ticket in his pocket and wondered about having dinner in some spot where it wasn’t likely that he would be recognized. But he didn’t have dinner anywhere. The strings of curiosity and all too bitter recollection tugged at him and drew him north, past 46th and 47th streets, the bitterness increasing as he walked, his mood becoming one of spit-in-your-eye defiance, his footsteps tapping out a kind of warning

“Trouble, trouble,” but he kept on walking, anyhow.

It was inevitable that he stop outside the Bowling Club, on a street just off Broadway, if only to make certain the place was still there. And it was there, all right. Arrows within a bold electric sign blinked off and on, making it clear to potential clients that the alleys were in the basement. 20 — MODERN ALLEYS — 20, the bright sign said. A man leaned idly against the entrance, scratching his back on the doorsill.

“They ain’t bad alleys,” the man said, “if you’re wonderin’.”

“I’m not wondering,” Danny said. He kept looking at the sign. “I ought to know. I used to own the joint.”

And because curiosity pressed stronger than mere prudence — though for no other reason clear to himself — he opened the door of the Club.

He stood at the head of the stairs. He could hear somebody’s laughter, big as a bomb burst, and wonder to himself what was so funny. He could hear the shuffle of soft shoes on the smooth and polished wood of the alleys, the long roll of the ball, and then the full blast of the pins in wild eruption.

He took a few steps down the stairs. Eight years, he thought. His left hand gripped the railing at his side, his other hand ‘swung free. He raised the free hand and looked at his strong, square knuckles — the armament of a fool, he warned himself. Eight years since he had swung the hand into the round and silken features of a man named Allie Fargis — a stupid reprisal, it had been, but all he could do at the time.

A few more steps. It had not been his conscious intention to come here, Danny was aware, though how much of each man’s time is spent in lying to himself, he could not say. His adult view that atonement via the muscles was the silliest and cheapest form of justice was something he still believed. Except that in this circumstance he didn’t trust himself. Don’t be a chump and land in jail, he thought, or in an alley with your head cracked like a dish. He was already at the bottom of the stairs.

This was not a crowded hour. A few men stood at the fairly distant bar, none of their forms familiar. A fat man and his companion were using Alley 6, the fat man sweating and merry, and the owner of the big laugh that had volleyed to the street. The fat man bowled with power and competence, his suspenders dangling from his pants.

Danny sat in a wide, newly upholstered chair in the spectator section. Only Alley 6 was now in use. A man swept cigarette stubs and scraps of paper into a catch-all pan at the end of a stick. Another man was placing empty pop bottles in cases, but Danny saw none of the boys who once had worked for him.

There’d been changes made in the bowling club, but none so radical, he supposed, as the changes time had wrought in the fabric of himself. Eight years ago? But how could it be that long, when it all kept playing over like a record in his head? No detail dimmed with time. No pages missing from the script.

“Hey, Danny!” someone had called. He’d been in a restaurant on Broadway — and occupied there with the cherry cheesecake, coffee and such strangely named places as Gasmata, New Britain, and Papua, New Guinea, where, according to the papers, the Japanese had landed to make a jolly time for no one but themselves.

He’d looked up, from the headlines and pictures. The headlines and the pictures and the world news tumbled into each man’s every day with such impact in 1942 that it was hard for a guy to keep straight in his head the name of the horse that won the second race at Hialeah.

“Danny, ol’ boy.”

“’Lo, Charlie.”

“Danny, ol’ kid,” said Charlie Binns, and Charlie, a theatrical agent, sat down. Charlie smiled broadly. He sighed. He patted the big envelope he placed on the table. He took a fork to Danny’s cherry cheesecake.

“Imagine runnin’ into you, ol’ boy.”

All right, imagine, Danny conceded; he had not seen Charlie in four hours, anyhow.

“And I could have waited another four hours.”

Charlie Binns collapsed. “You kill me, Danny.”

“Just hand me the fork, without my cheesecake on it, Charlie, and I will happily stab you to death.”

“Ol’ Danny,” said Charlie with commercial affection.

Old Danny in your hat, and that was the good thing about it. He was young. He was young and cocky and chesty as a robin that had stolen worms from eagles. He was twenty-four, and would have had the world in his pocket, if it didn’t seem at the moment to be in Hitler’s. He owned the bowling club and an uptown haberdashery shop; he owned half a race horse and one third of a fighter; he was such a helluva young man on the Broadway scene that he had once been worth nearly half the money that people imagined him to be worth.

“Runnin’ into you like this,” said Charlie, “when I have a perfect hot cake of a proposition — well, an opportunity, let’s say, kid — that only two real friends could sit down man to man an’ talk about… You listenin’, Danny?”

He had not been listening, really. He’d been looking around. Uniforms were blooming in the days of February, 1942 — not so plentifully as later, perhaps, but in conspicuous numbers, and khaki, in the scheduled stops of the town, had become more honored than mink. There was excitement, drama in the air; and fear there was, too, though the fear was dwarfed by the national muscle that all good people seemed willing to flex together. Danny waved to friends. He saw Georgie Jessel, seated with his mother; Georgie waved; Jimmy Durante, Milton Berle; band leaders he knew. He waved to a good-looking man named Allie Fargis, who sat at a table with a better-looking woman. An important fellow, this Allie Fargis — for reasons not very clear — but always pleasant; charming, even. And there was a little girl named Ruthie, a ballet dancer. She waved to him, and Danny waved to her. Show people. If not his kind of people yet, then the kind he wanted to know. Show people and show business — the soft spots in his heart and in his head.

“What’s that, Charlie? What are you trying to sell me?”

“I said this is it; the play you been lookin’ for, Danny. I say if a man wants to be an angel for a show, an’ make a medium-sized mint, let’s say, for puttin’ up a lousy fifty grand — an’ especially if he’s a sweet an’ personal friend — well, I wanna give ‘im the best kind of wings to start with, don’t I?”

“Do you?”

Charlie passed the bulging envelope. “Read it! I dare you!”

Danny grinned. He shook his head. He pressed the envelope back on its bestower.

“This angel escaped through his halo, Charlie. Sorry. I’m gonna outsmart my draft board any day now by enlisting. So that even if this bundle was a Camembert an honest man could take the lid off, Charlie, I wouldn’t be —”

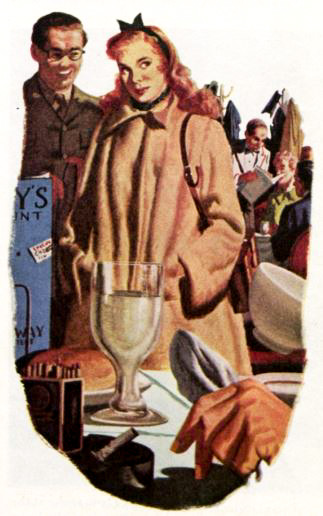

That was when he saw Caroline Shane for the first time. She was standing with a soldier, not far from their table. She wore no mink. No Hollywood goggles. No conspicuous assistance from a drugstore. Nothin’. Just a girl in a camel’s hair coat buttoned high, with her hands in the slanting pockets of the coat and the color of the cold night in her cheeks. Her hair was soft and abundant and tumbled to her shoulders. She smiled at him then, a little nervously, but as though she knew who he was, and the soldier might have been a double-decker sandwich on a plate, for all that Danny noticed him in that first moment.

But Charlie Binns stood up. “Danny, I want you should meet the author of this play, this terrific piece of work Danny,” said Charlie, “this is David Bowen.”

“Well, hello.”

“And this,” Charlie said, presenting the girl, “is a friend, but high class, Danny — an intellectual friend, you might say, of the author.”

“On the level?” Danny looked at the two young people. “You’re always hearing something new these days,” he said. “What’s an intellectual friendship, Charlie?”

His tone might have been more cynical than he intended it to be, and David Bowen answered him. “I think Charlie’s trying to say that an intellectual friendship is his idea of the best arrangement that can be made with a girl whose family has raised her carefully, who is determined and absolutely certain to stay that way, and is also bright in the head. That help?”

“I think so,” Danny said. “In fact it cooks me like a blintze. And, incidentally, I wasn’t trying to be smart.”

Things improved then.

David Bowen and the girl sat down. Private Bowen, of the United States Army, was dark and slender — a tall, thoughtful boy, hardly older than Danny himself, and not entirely at home or beautiful to behold in the random tailoring provided by the Army.

“David’s at Camp Dix now,” Charlie said, “an’ it lets him get into town once in a while. He is doin’ a perfectly sensational job at Camp Dix… How about that, David?”

“I’m doing a sensational job dunking underwear in the laundry,” David said; “the Axis is worried.”

“Always modest, always modest,” Charlie said. “And Caroline here, this little girl, has consented to read a few bits from the script — the more sensational parts, that is — doin’ maybe four, five characterizations, like a one-man band, the darlin’, just to rough you in on what a quality piece o’ work we got here, Danny.”

“You’re an actress, Miss Shane?”

“From morning till night,” Caroline Shane said levelly, “I am acting, sir — like yeast.”

“Radio,” Charlie explained. “Aye-em an’ ef-em, from aye-em to pee-em. The best. An’ for dramatic experience —”

“A station you never heard of, in Long Island City,” Miss Shane said.

“Shut up,” Charlie said. “Excuse me… Well, Danny, look, I figured July 15, 1950 maybe we would all go up to your apartment an’ let you see for yourself why there’s a fortune in this thing.”

Danny said nothing for a moment. The reasonable, prudent thing to say to any Broadway party with a package was “Get lost.” But he was looking at the girl, and at the soldier, too; and quality of any kind had a way with him.

“What have I got to lose?” he said.

“My money?” He called for the check and enjoyed the role he was playing. They had walked out of the restaurant, the four of them, past all the celebrated people who knew his name and fattened his pride, past the cheesecake and the sturgeon and the pickles and the marinated herring — past Allie Fargis, even, who looked up and said to him brightly, “It’s nice to see you, kid.”

“It’s nice to see you, Allie,” Danny had said — a long time ago, when he was very young, and had that gaping hole in his head.

He lighted a cigarette and looked around the almost-empty bowling club. He knew very well that this was April, 1950, and that there was nothing he could do to make liars of clocks and calendars.

David Bowen’s first play was in rehearsal by April of that other spring. It was a topical drama, timely as a Wac’s hat, and challengingly called A Million Miles From Munich, and if it wasn’t so good as Danny thought at the time, it wasn’t a turkey, either. It had vitality and conviction and it reflected the thoughtful decency of the young man who wrote it. For Danny’s part, he tumbled dollars into the production without complaint or qualm, and for more elevated reasons than the one most quoted by Charlie Binns: “This ain’t a play, Danny; it’s a mint in three acts.”

His love for the theater was valid. He had been a star-eyed goon for its magic, and a starch-shirted regular at first nights, since, at the age of seventeen, he had run the hot dog, lemonade and popcorn concessions on a string of ferryboats and made more money than was necessarily good for a parentless, knock-about kid who, by the general standards, ought to have been in school.

“I suppose I always wanted to be a big shot,” he said one afternoon to Caroline Shane.

“But you are a big shot, Danny.”

“Me?”

“How big is big?”

“I’m a mug,” he said.

It was a half-pout, really, designed for drawing reassurances from her that he was perfectly wonderful. This was a fault in himself that he recognized. But he had made the statement with sincerity, too, and mainly because in the two months he had known Caroline and David he had come to consider his own bizarre and dollar-catching career as honest, perhaps, but not exactly edifying. It was certainly not the sum of things he once believed it to be. Too often they talked of matters he didn’t know about — not the theater, for here he was well read and almost too knowingly glib, but all the other things they had learned by studying when he was peddling popcorn, punching noses, hawking and promoting himself toward the dazzling goal of a wardrobe filled with $100 suits and, it seemed to him now, a half-filled head. He told her these things.

“You see what I mean?”

“I think so, Danny; yes. I think you’re studying to be a snob, instead of being yourself. But you’re you, and you’re growing, Danny, and you’re original and brave and generous and —”

“And what?” he said.

Well, she didn’t say just what. They were seated on the floor of his living room — Caroline, himself and Charlie Binns — at least supposedly occupied with various sketches that stage designers had submitted. But work had not progressed. David, with the crucial matter of Army underwear at Camp Dix, had not been able to attend. They listened for a while to the radio news. Charlie said it was too much to expect a man to think on a day like this. He said that what Hitler needed most was a rousing kick in his silly mustache, and then walked off to the ball game.

“Well,” Danny said, “we were talking.”

“About the sets,” she said.

“Not about the sets.”

She was very close to him, sitting on the floor, legs folded under her, a wisp of hair dangling in attractive disorder, a yellow pencil clamped in fine teeth, her fingers smudged a little from the sketches.

“Then let’s try to talk about the sets,” she said.

Just the two of them, and the springtime walked in through the wide and welcoming windows in a single stride. It hovered about them while the curtains moved at the windows and the light breeze touched her hair. And they couldn’t talk now. They were suddenly no good at it. Caroline looked away from him, the sketches crinkling when she shifted her legs. It wasn’t news to either of them that the moment had been building.

“Look at me,” Danny said. “Try it once, for laughs.”

Then she raised her gaze to his. Her large eyes were soft and full of him. He took the damp pencil from her mouth.

“Who’s laughing?” she said.

Then he kissed her, for the first time. Not very boldly, but lightly, almost experimentally, with reverent tenderness. Her breath was warm and her eyelashes touched his cheek. And after a little while she stood up and said to him, “This would be the right time, darling, for us to go for a walk, and for you to buy me a soda — pineapple, maybe, with vanilla cream.”

He ached all over. “You’re not fooling?”

“This is no time for fooling,” Caroline said.

A few nights later, David Bowen looked across a table at the two of them. Time had made him a better dressed soldier and his shirt was now only two sizes larger than it should have been around the collar. He wore the single chevron of a private, first class, and a fair imitation of a smile.

“So it’s love,” he said. “You can’t fight City Hall. Why tell me you’re sorry? And who’s surprised? Me?” David looked away. “I didn’t want to tell you this, kids, but I’m in love with a Wac at Camp Dix. You can send us a piece of the cake.”

It really hurt him no more than a swallowed bayonet. Caroline kissed him and Danny just sat there. There wasn’t much you could say to someone like David. The logical thing was to build a statue of the guy and have it placed in a public park.

Danny walked through 48th Street the following day and stopped at the bus depot. He had misgivings, but was determined to be direct. He walked up to Patrick Shane, who was on duty checking the outgoing busses, and said to Caroline’s father, “This is for your daughter.”

The three-carat stone in its solitaire setting gleamed like a torch in the daylight. Patrick Shane scratched the back of his head.

“Put a blinker on it,” he said, “or you’ll blind the girl. We’re not fancy people, son.”

“You don’t like it?”

“Yes, I like it well enough. Who wouldn’t? But the only thing about me that ever shone like that stone, Danny boy, is the seat of me pants. It’s yourself she’ll be getting, more than the ring.”

“She could do better,” Danny said.”

I suppose she could, at that, but she could do a lot worse, too, if she tried real hard.” Patrick Shane then gave his attention to Bus No. 14, bound for Cleveland. He came back in a few minutes. “When’s the big event, Dan?”

“After the show opens in New York, we think, and before the Army wins me.”

“A war bride? My little girl?”

“I know what you mean, but it’s one of those things,” Danny said. “It’s the way we feel about it, anyhow. I wanted to ask your permission. Your blessing, kind of. They tell me that’s the way nice families like to have it done.”

“You’re marrying each other,” Patrick Shane said, “and the blessing’s God’s business more than it’s mine. I hope He takes care of you both.”

Danny walked back to the bowling club, where Charlie Binns was sitting in the office. Charlie had things in his hands.

“These ain’t score cards,” Charlie said brightly. “These are bills. Accounts payable, angel, an’ like I always said, you gotta spend a few dollars to reap the golden whoilwind. Forty-four hundred an’ twenty-six bucks. We go into Philadelphia for the tryout this week end, kid. We’ll wake up Benjamin Franklin. You don’t have to do any of the hard work, kid; all you have to do is loosen up your arm an’ write a nice little check for these items.”

But Danny kept his hands in his pockets. “I can sign a check as well as a Rockefeller, Charlie. My only trouble is that I haven’t got any money.”

Charlie Binns looked like a kid around whose neck Santa Claus had suddenly bent the electric trains. Danny enjoyed his expression, but also chose to be merciful.

“I mean I haven’t got it at the moment, Charlie. Next week we’ll be all right, but there’s a little matter of converting assets.”

“Assets is different,” Charlie said. “Assets I am willing to discuss.” But he remained suspicious, wary. “How about that fighter you’ve got a piece of? That meatball — what’s-‘isname?”

“He’s fighting for the Army, Charlie, for thirty dollars a month. I can’t take a percentage of that, can I?”

“I don’t know,” Charlie said. “Did you try? And how ’bout your race horse?”

Danny shook his head. He put his feet on the desk. “Gotham Girl?” It hurt a bit, but it had to be faced. “She broke down at Pimlico a week ago, Charlie. She was the fastest three-legged horse in the race and I had a bundle on her too. There’s a nice bill from the trainer in the second drawer on the left.”

“Hell, I’m sorry, Danny. Honest. I’m not the worst ghoul in the world. I don’t always feel as commercial as I sound. How ’bout the haberdashery shop?”

“At the moment,” said Danny, “business stinks,” and he wasn’t fooling. “We don’t carry khaki.” And yet he saw no blackness of prospect that could not be brightened readily enough. He looked around his office. “I can always sell this place, can’t I?”

“But this is your living, kid. The alleys are bread and butter.”

“Where I’m going, Charlie, they feed you for free. You get a nice brown suit and new shoes when you need them. You know Allie Fargis, don’t you?”

“What about him?”

“Well, he’s a nice guy.”

“Is he?” Charlie, somehow, did not look convinced. “Why is he a nice guy?”

“Because he’s willing to buy this place for sixty thousand dollars, as is.”

“Allie? Did you talk this over with the district attorney?”

“Look, Charlie; that’s the way too many people are — suspicious all the time. Imagination has ruined more reputations than whisky. He’s been nice to me, so I say he’s a nice guy. I don’t want his pedigree; I want his dough, and ten days from now we’ll be using it to open the show in New York.”

It was, to be sure, a pleasure to do business with Allie Fargis. Good manners are a dividend in any relationship, and because a man took bets on horses, it didn’t necessarily mean he was a thief. Bookmakers, like undertakers, had essential services to offer.

“Any objection to cash?” said Allie.

Danny grinned. “Do I look queer?” There was a three-o’clock train to be made to Philadelphia. “Just count it out,” he said.

The nice crisp stuff. Mostly in hundreds. Green as lettuce; $60,000. The undebated asking price of the bowling club, lock, stock and long-term lease on the basement of the building. The landlord, satisfied, and the landlord’s wife, were witnesses.

Allie’s lawyer was a pleasant fellow too. They all had a drink. “You sign on the X’s, Mr. Meade; it’s simple as ticktacktoe.”

The landlord and his wife departed.

“Well, good luck with the show, kid,” Allie Fargis said.

“I think we’ll have good luck.”

“And, of course, it’s none of my business,” Allie said, “but if I were you, I wouldn’t just carry that money around like a loaf of bread. Do you have a safe-deposit box?”

But it was a Saturday afternoon and the banks were closed. Danny thought about this for a moment and there wasn’t much time for catching his train. Allie Fargis made no suggestions. It was Danny who looked up at the wall safe, no longer his own.

“Would you mind?” he said.

“Hell, no, kid; not if you don’t. Help yourself. My lawyer’s a crook,” he added disarmingly, “but you’re the only one who knows the combination. I think we can all relax.”

As Allie’s lawyer had said, everything was simple as ticktacktoe. Like spreading mustard on salami. Like shooting a duck in a tub. And the curtain went up at the Philadelphia tryout and a few hours later came down. Danny sat with David Stern, and between them, perhaps, they had seen the play a few too many times.

But the people liked it in Philadelphia. The distinguished critic from one of the Philadelphia newspapers did not stand up and whistle with glee. But he came seeking David, and shook his hand, and said to them both, with solemn approval, “I’m afraid you’ve got something pretty good here, boys. I think that with a little bit of fixing they’re going to like it in New York.”

They celebrated unwisely, the two of them, and Caroline put them to bed. The cast was threatened with eviction from one of the city’s best hotels. It was one of the gayest Sundays ever known… in Philadelphia.

Danny walked into the bowling club on Tuesday. He walked in a kind of personal cloud. He stopped at the head of the alleys and called to one of the pin boys, “Set ’em up!” for no particular reason. He was by his own admission the weirdest bowler New York had produced since Rip Van Winkle, but he let one go, for luck. The ball thumped on the boards and rolled erratically. Five pins were tumbled.

“Three more than my average,” Danny said.

“Who are you?” somebody inquired. The somebody was large, of obvious Broadway extraction, but as yet unknown to Danny.

“I’m a jack rabbit named George,” Danny said. “I’m the boy who owned this place till Saturday.”

“Today is Tuesday, Mac; don’t try t’ louse up the alleys.”

“And who are you?”

“They call me Sugarboy,” the big man said.

“You work here?”

“I work here. So?”

“So go sit on this thing till it hatches.” He placed the bowling ball in Sugarboy’s hands. He walked the length of the alleys and opened the office door.

“Hello, Allie.”

Allie Fargis sat at the desk. “Mr. Show Business, huh?” said Allie. “How’d everything go?”

“Like a B-Twenty-nine, Allie; we’re in, I think. Say, who’s that meatball outside?”

“Sugarboy?”

“I don’t mean Uncle Don.”

“Sugarboy,” Allie Fargis said, “is a kind of insurance policy I picked up cheap, if you know what I mean.”

“No, Allie; I don’t know what you mean.”

But misgivings were settling heavily inside him, like three dollars’ worth of gum drops. He stepped over to the small safe in the wall, seeing that the plaster has been disturbed around its edges and thus far hadn’t been replaced. His hand went to the dial and turned and turned and turned it in the formula he knew. But nothing happened.

“Allie,” he said. “Allie, boy.” He spoke with deliberate control, though his hand trembled on the dial.

“You mean the combination, kid? Well, naturally, I had it changed. You can’t afford to take chances these days, and I’ve got a pal with a reputable firm. Double time for working on Sunday, I had to pay the bum, just for a new combination.”

“Open it, Allie — open it!”

“What’s the use of getting excited?” Allie asked. He opened the safe very simply and the safe was very empty.

“The first of April was weeks ago,” Danny said. “Practical jokes are out of season, Allie. Where’s the sixty thousand dollars? Where’s the money I put in the safe?”

Allie looked at him with mock surprise.” You mean you’d be silly enough to put that kind of money in somebody else’s safe?” Allie’s smooth face was pitiless, his eyes amused. “How many witnesses did you have, kid?” As simple as that, and his expression told the rest. “Unofficially,” he added, “I’d say I bought the place pretty cheap.”

It added up, didn’t it? No witnesses, because the landlord and the landlord’s wife had only seen Danny with the money in his hands. They hadn’t seen him put the money in the safe. The other witness was Allie’s lawyer.

“It’s funny you should have these delusions,” Allie said, “when my own lawyer saw you walk out with the cash.”

Danny hit him then. Danny, more than a little bit crazy, swung his fist in a crushing arc that spun and staggered the smiling man before him, and sooner than Allie could topple to the floor, he hit him again, and again, the large body changing the direction of its fall and collapsing heavily, the left side of the blank face then colliding with the metal edging of the desk.

Allie Fargis lay as though dead, the side of his face opened wide as a hatcheted melon. Danny stood over him, his fist still throbbing with the contacts it had made.

I killed him, he thought; the guy is dead. And he almost didn’t care.

The office door opened and Sugarboy Spartano stepped inside. His long jaw hung loose in an imbecilic stare.

“Come near me, you meathead, and I’ll kill you,” Danny said softly. He walked toward Sugarboy with a paperweight clenched in his fist, and Sugarboy, his own hands empty, backed away. “You’d better call a doctor,” Danny said.

He kept on walking. He paused at the top of the stairs, close to the street. He clung to the railing there, remembering Allie Fargis’ face, and not knowing whether to run away or go directly to the police.

He went home and phoned Charlie Binns, “I want to see you, Charlie; come over.”

He sat for a while, seeking to assess the likely cost of his trust in Allie Fargis, and his sense of stupidity and personal shame became greater than his rage had been.

“Go to the cops?” said Charlie Binns. “Well, I dunno. First of all, you didn’t kill the guy; I checked on that. He’s in Polyclinic Hospital, and if you wait a bit, the cops’ll come to you. Allie’s no dope; he’ll use the law as far as he can, so why be in a hurry to get yourself locked up? Think again, Danny. You have no one to testify you put the money in the safe?”

“No one,” Danny said.

“Then you know something?” Charlie looked at him sadly, without rancor. “You’re a nice kid, Danny; I always liked you. And I hope the Army’s able to fit you to a brand-new set of brains.”

David Bowens play didn’t open in New York. Risk capital was rare around Broadway at the war’s beginning, and angels all too few. A topical drama, subject to changes in time and public appetite, A Million Miles From Munich never opened anywhere.

But Allie Fargis survived very well. Charlie Binns found out on the same afternoon that a warrant had been issued for Danny’s arrest. Life could prove sweeter in some other part of the country, Charlie suggested.

“I’ll speak to Caroline and David. Hell, I know how you feel. And thanks for the moonbeams,” Charlie said.

Danny took a train to Boston. He walked into a recruiting station there. And the Army wasn’t too fussy in 1942.

Yes, there’d been changes made, all right, in the bowling club. Danny could see that a fancier set of lights had been installed, and the price per game had been raised a dime. The bar, it occurred to him, if distant still from where he sat, had been moved about twenty feet forward from its original position. He wondered, naturally, what was currently in back of the bar, in the additional space that had to be there, and a man coming out of a door that had not existed eight years before gave him a pretty fair idea, even though the door itself bore the vaguely innocent lettering, SUPPLIES.

Other men left the supply room in the next ten minutes, but they left discreetly, in couples or singly, as though by mannerly schedule, and they were obliged to pass the place where Danny sat; some of them groomed a bit too perfectly, none of them shabby; attitudinal and poised men, these, walking with short steps, both the winners and the losers; wise guys, “I’ll-fade-the-other-five-C’s” kind of people. Danny kept staring into his lap, his back to them, himself in the shadows. He hoped he was not noticed as they passed.

After a little while he got up from the chair and casually walked the length of the place. Having no better, more sensible destination, he went into the men’s room and mechanically washed his hands. He tugged at a roller towel and was ashamed to find his fingers trembling. He did not think of himself as a brave man, nor as an especially resourceful one. But when he went outside again and looked around, he was convinced he had attracted no one’s close attention. Just in front of him was a door marked OFFICE; and it was a curious thing that by doing no more than putting a hand into a pocket he was able to produce a key that once had fitted this door — a kind of useless relic he had retained from the days when the alleys had been his. Any other thought about the door and this particular key would be preposterous. Well, wouldn’t it?

Don’t be a chucklehead, Danny boy. There’s not a chance.

But the temptation was strong at least to try, and curiosity stronger still. How could you tell if you didn’t try? He could hear only the fat man’s laughter, hah, hah, booming, and he could see nobody near. Very carefully then, very softly, he put the key in the lock; he turned the key and the door came open, not even squeaking, but yielding like a curtain to the pressure of a hand.

There was no one in Allie Fargis’ office. He closed the door behind him. He stood there. The room bore more of an executive look than it had possessed in the days of his own tenancy. But this was consistent with the man who occupied it now, since Allie Fargis had more style than a forty-dollar necktie. And the single photograph on the polished desk was of Allie himself. The wall safe was in the same position it had always occupied. A noiseless electric clock said: 7:34. A new door had been built into the wall he was facing, and this connected — because it had to connect — with the space so innocently labeled SUPPLIES.

He sat at Allie Fargis’ desk in fascinated muse. The tension mounted. Nobody here at all, he thought; just me, but with the quiet hanging heavy as a shroud. And what he would do when someone came into the room, he did not know. What if one or more of Allie’s personal and muscular monkeys came in? There was no answer to that one either.

So he sat facing the new door, waiting. He began to sweat, and knew that he was sweating. He opened the top drawer of the desk; just papers. Another drawer; about two dollars in change and a bottle of aspirin tablets. A third drawer then; an automatic pistol, stubby, polished, efficient-looking. It was not the kind of item that consoled him, but he put it in his pocket, preferring it to be in his possession, if possessed it had to be.

A key turned in the door and the door came open a little bit. He stood half out of the chair, then compelled himself to settle back. The key was; withdrawn from the lock; he could hear it being withdrawn. The door came open all the way, but slowly, before the pressure of Allie Fargis’ shoulder; and Allie came into the room, his large hands holding a square foot of money, and his eyes, understandably, on the money alone. Allie let the door swing closed behind him before his glance came up to meet the image of the man behind his desk.

“Hello, Allie.”

Allie Fargis dropped most of the money. It fell to the carpeted floor in tidy stacks, as lightly as tumbling kittens, and the big man’s loose mouth just stayed open in a kind of aching, stupid stare, as though the mouth would never close again or ever make a sound again. And it was this way with Danny, too, for there was a numbness in his head that made it feel like a squeezed squash, and when sound came out of it, it came as a surprise.

“When you get your breath, Allie, don’t scream. Drop the rest of the money, Allie; drop it.”

His own voice, but it was more as though he eavesdropped than participated, and there was not in him for the moment strength to rise; it was a moment so different from any conceived in the dreamed or fancied dialogues eight years of thinking- about a meeting with Allie Fargis had provided. The money was the difference. The money, the money, he realized; the money was, of course, the thing so fantastically unexpected. Because never had he been able to picture Allie standing before him like a two-legged Irish Sweepstakes.

“Drop it all, Allie. Now step away from it.”

He was able finally to stand up and to walk around the desk with some fair imitation of assurance, and with the gun in his hand like a prop in a play. He was able to walk on the fat rug, over the big fat money, with Allie backing away from him, with Allie trying so very hard to bring blood and life into the sick, dead smile on his face.

“You’re rollin’ yourself the wrong kind of hoop, boy,” Allie said. “There’ll be people in here in a minute. Maybe five or six of them.”

“I’ll take my chances, Allie. Why don’t you call them now?”

“You’re a laugh a minute.”

“Am I?”

They looked at each other and Allie didn’t think he was a laugh a minute. Old memories did more than stir; they spun like tops, and there was little comfort in the past. Allie Fargis was a large man in his forties — a handsome and even a pretty man. The scar that ran the length of his left cheek could have been made by tailor’s chalk, and it was surely not the disfigurement it once had promised to be. This was Allie Fargis, still the barber’s delight, and by weight of the information gathered by Danny in the years between this evening and the last time they had met, one of the feared, unjailed and important thieves of the town. Hit him, Danny told himself; hit him, hit him, hit him. It was the only thing to do. You either hit him or shot him, because you couldn’t ignore the money, and the money belonged to you.

“Look, kid,” Allie said. “Be smart.”

Then Danny hit him; not with the gun, but with a smashing right hand, once, twice, and then again, the last two punches piercing Allie’s raised hands in their not very knowing posture of defense. And he was very good at hitting Allie Fargis. He could put his heart into the work. The big man crumbled forward and Danny caught him, let the weight down easily. Allie Fargis wasn’t fooling. He was out.

Danny gathered up the tumbled stacks of money, no doubt intended for deposit in the wall safe — tidy packages of odd denomination, with nice bank wrappings around them, their separate totals legibly marked: “$1000, $750, $2500” — convenient for rough addition of the whole amount. He did not think they would total $60,000, but they did. There was even a little left, and this he tossed on the desk. He took a newspaper from the seat of a chair and spread it wide, in triple thicknesses, and wrapped it up as well as haste would allow.

He opened the door through which he had entered, but saw no one. More frequently now than when he had come in, he could hear the crash of action on the alleys, the smash of the heavy ball, the clatter of the pins. Business was improving. He walked at a controlled and held-together pace the length of the bowling club, his nondescript package under one arm. He knew it was not yet eight o’clock, but customers were coming in as he was going out. He saw Sugarboy Spartano, but Sugarboy did not see him. The urge to spring was almost overwhelming, and restraint was a kind of physical pain.

He did not run. Logic told him to get away; he’d got the money back; it was his. He hadn’t dreamed that in ten thousand years he’d get it back. Leave the car where it happened to be, at Twenty-Third Street, in the parking lot. It was an old heap, anyhow, and if he were stopped and the money found on him, he couldn’t prove he hadn’t stolen it from Allie.

Was he thinking clearly on these things? Or was he muddleheaded now, as he had been eight years before?

Ahead of him on 48th, he saw the coast-to-coast bus depot, and the big jobs wheeling in and out of it, their destinations known to him: Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis, Denver — and a posted notice that said very clearly: “Once a bus crosses building line, it is not permitted to stop and pick up passengers.”

This, then, he thought, might be the way. He thought this because he did not at first see Patrick Shane, the traffic foreman of the depot, who emerged now in his uniform from behind one of the busses. A tall and weathered-looking man, was Patrick, straight as a stick at the age of sixty-five.

Danny saw him barely in time to avoid being recognized. Automatically, he got away from there, walking faster with his package, not knowing for the moment what means of escape from Allie Fargis and Allie’s dear boys ought to be employed. Two we ten got out of a taxi in front of a restaurant. Danny stepped into the cab. The driver looked at him.

“Where to?”

“Penn Station,” Danny said.

At Penn Station, for a dime dropped into a slot, he was able to acquire a twenty-four-hour lease on a squarefaced locker, No. D-324, the third row, seventh from the left, and into it he tossed, as one might heave a burdensome, newspaper-wrapped pair of overshoes, exactly sixty thousand dollars. He put the key in his pocket and heard it clink rather merrily against the key that had opened Allie’s office door. It was a pleasant feeling. It was good. But it didn’t wipe away the shame of running from Allie Fargis with money that was his own. Why had he come to New York, anyhow? To see one show? To gape, lovelorn, at Caroline? Yes, that was why, he admitted to himself; it was exactly why, but how much was it worth?

He had a glass of milk and a sandwich at a lunch counter in the station and tried to make up his mind. He walked outside the station and the big clock at the east end said it was 8:17 o’clock — twenty-three minutes to curtain time.

Run now, Danny? Get out of town? Live to see your old age, Danny? With money in the bank? Who, me? He felt the theater ticket in his pocket. He called another cab. “The Judson Theater,” Danny said.

Illustrations by Geoffrey Biggs

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now