When he died, in 1970, Erle Stanley Gardner was the best-selling American fiction author of the century. His detective stories sold all over the globe, especially those with his most famous defense attorney protagonist, Perry Mason. His no-nonsense prose and neat, satisfying endings delighted detective fans for decades. Gardner wrote several stories that were serialized in the Post. In Country Gentleman, his 1936 serial “The Thread of Truth” follows a fresh D.A. in a clergyman murder case that comes on his first day on the job.

Published on September 1, 1936

The room held a subtle atmosphere of burnt-out activity. Physically, it had the littered appearance of a vacant lot from which a carnival had moved away. The walls were decorated with posters. “ELECT DOUGLAS SELBY DISTRICT ATTORNEY” screamed one poster. Above the words appeared the likeness of a handsome young man with curly hair, a devil-may-care glint in his penetrating eyes, and a forceful, although shapely, mouth. Hanging beside it, a twin poster showed a man some twenty-five years older, wearing a big sombrero, his leathery face creased into a friendly smile. It required a close inspection to show the hard determination of the gray eyes. That poster bore the words, “VOTE FOR REX BRANDON FOR SHERIFF.”

Half a dozen small desks and tables had been crowded into the room. They were littered with envelopes, pamphlets, windshield stickers, and other campaign paraphernalia.

Douglas Selby, newly elected district attorney, grinned across the room at Sheriff Brandon. It had been a bitterly contested battle, involving an election contest, a recount of ballots, and an action in mandamus. The actual election had been history for weeks, but the political backers of the two men had kept the room in the Madison Hotel for post-election activities.

Selby, crossing his long legs, ran his hand through his thick shock of curly hair and said, “Well, Rex, in fifteen minutes we start for the courthouse to take charge. Personally, now that it’s all over, I’m going to miss the fight of the campaign.”

Rex Brandon fished a cloth sack from his pocket, shook flakes of tobacco into a brown cigarette paper. His thick fingers rolled the cigarette with an expert twist. He moistened the edge of the paper with his tongue, stroked the cigarette into a smooth cylinder and said, “You’ll have plenty of fighting, son. It ain’t all over — not by a long ways.”

Selby had the knack of completely relaxing his muscles when he was at ease. He seemed as completely untensed as a cat sprawled in the sunlight. “Not much they can do once we get in office,” he drawled.

Sheriff Brandon snapped a match into flame with a quick flip of his thumbnail. “Listen, Doug, I’m twenty-five years older than you are. I haven’t got as much book learnin’, but I know men. I’m proud of this county. I was born and raised here. I’ve seen it change from horse and buggy to automobile and tractor. I remember when you’d never walk down the street without stopping three or four times in a block to pass the time of day with friends. Now things are different. Everyone’s in a hurry.”

The sheriff paused to apply the match to the end of his cigarette.

“What’s that got to do with us?” Selby asked.

“Just this, son: People used to know pretty much what was going on in the county and officeholders used to get a square deal. Now people are too busy and too selfish to care. They’ve got too many worries of their own to bother very much about seeing that other people get a square deal.

“If it was just politics, it wouldn’t be so bad. But during the last four years the doors have been opened to all the scum from the big cities. Chaps who haven’t been big enough to work a racket in the Big Time have drifted in with a lot of little, vicious, chiseling, crooked stuff. Sam Roper, the old district attorney, either got a cut or should have had one. You know that as well as I do.

“Now, then, it’s up to you and me to clean up this mess.”

“It’s already cleaned up,” Selby pointed out. “The crooks read their death sentences in the election returns. They’ve been getting out. Little hole-in-the-wall joints have closed up, or turned honest.”

“Some of ’em have, and some of ’em haven’t,” Brandon said. “But the main thing is that we’ve got to watch our step, particularly at the start. If we make just one major mistake, they’ll hoot us out of office.”

Selby looked at his watch, got to his feet and said grimly, “It’s going to take a lot of hooting to get me out of office. Come on, Rex, let’s go.”

Campaign headquarters had been located on the top floor of the Madison Hotel. As the two men stepped through the door into the carpeted hotel corridor, a door opened midway down the hall on the right-hand side. An apologetic little man, attired in a black frock coat and wearing a ministerial collar, slipped out into the hallway. He seemed to be tiptoeing as he walked rapidly toward the elevator and pressed the button.

It was several seconds before the elevator cage rumbled up to the top floor, and Douglas Selby utilized the time studying the little minister. He was between forty-five and fifty-five, and fully a head shorter than the district attorney. The small-boned frame seemed almost fragile beneath the shiny cloth of the well-worn frock coat.

As the elevator operator opened the sliding door, the little clergyman stepped into the cage and said, in the precise tones of one accustomed to making announcements from a pulpit, “The third floor. Let me off at the third floor, please.”

Selby and the sheriff entered the elevator. Over the top of the minister’s unsuspecting head, Rex Brandon gave the tall young district attorney a solemn wink. When the elevator had discharged its passenger at the third floor, the sheriff grinned and said, “Bet there’s more funerals than weddings where he comes from.”

The district attorney, immersed in thoughtful silence, didn’t answer until they were halfway across the hotel lobby. Then he said, “If I were going to indulge in a little deductive reasoning, I’d say his parish was controlled by one very wealthy and very selfish individual. That minister’s learned to walk softly so as not to offend some selfish big shot.”

“Or maybe he’s that way because his wife has a natural talent for debate,” the sheriff grinned. “But, say, buddy, don’t forget that this speculating business ain’t just a game. Did it ever occur to you that during the next four years whenever a crime’s committed in this county it’s going to be up to us to solve it?”

Selby took the sheriff’s arm and headed toward the white marble courthouse.

“You solve the crimes, sheriff,” he said, grinning. “I simply prosecute the criminals you arrest.”

“You go to the devil, Doug Selby,” the sheriff rumbled.

II

Douglas Selby had been in office just twenty-four hours. He surveyed the littered material on his desk, reached a decision and summoned his three deputies.

Waving them to seats, he studied the three men. Frank Gordon, full of a black-eyed, youthful enthusiasm; Miles Deckner, tall, gangling, slow of speech, with straw-colored hair; Bob Kentley, a holdover from the other regime, a studious, rather innocuous individual, with a bulging forehead, horn-rimmed glasses, and eyes which had a habit of staring intently at the floor near the tip of his shoe.

“Boys,” Selby said, “I’m tackling a job I don’t know much about. You boys have got to carry most of the load. You, Gordon, are full of energy and enthusiasm, with a great capacity for work. You don’t know as much about this job as I do, and that’s next to nothing. You, Deckner, aren’t as fast a worker as Gordon, but you’ve a certain native caution, which gives you a pretty good perspective. You, Kentley, were loyal to Sam Roper, the former district attorney. Frankly, the only reason I kept you on was because you knew the routine of the office. I suppose you’re wondering what your future is going to be. Is that right?”

Kentley kept his eyes lowered and nodded.

“Go ahead,” Selby said, “speak up.”

“I figure,” Kentley remarked sullenly, “that you’ll let me go as soon as I’ve broken in these other two deputies.”

“All right,” Selby told him, “forget it, and snap out of it. Quit being sullen. You aren’t ready to go out and tackle private practice. You need the job. You fought me during the campaign, but I figure you know something about the office, and I think you’re honest. I figure you worked against me because you wanted to hold your job. Now I’m going to give you a chance to hold it.

“You play ball with me and I’ll play ball with you. It’s up to you to instruct these boys in the duties of the office. Among you, you’ve got to handle the routine. I’m going to hold myself in reserve for the big things.

“Here’s a bunch of stuff which has piled up on my desk. There’s everything here, from a complaint about a neighbor’s dog scratching up a front lawn to a tip that a next-door house is a speakeasy. You boys take this stuff into the law library and divide it up. Don’t write any more letters than you have to — telephone people, get them to come in, reason with them, straighten things out by diplomacy. Don’t fight unless you have to. When you once start to fight, never back up. Remember that The Clarion will give us a square deal and The Blade will be fighting us all the way. You’ll make mistakes, but don’t let the fear of making mistakes keep you from reaching decisions. Whatever happens, don’t let anyone bluff you. Whenever you … ”

The telephone rang. Selby said, “Just a minute until I see what this is.”

He held the receiver to his ear and said, “Hello.”

Rex Brandon’s voice, sounding rather strained, said, “Doug, drop whatever you’re doing and come down to the Madison Hotel right away. They’ve found a dead man in one of the rooms.”

“What is it,” Selby asked — “murder, suicide or natural death?”

“They don’t know. They say it’s a minister … I have an idea it’s the same chap who rode down in the elevator with us yesterday.”

“Where are you now?” Selby asked.

“I’m at the City Hall, picking up the chief of police. We’ll get to the hotel a few minutes before you do. The room is number 321. Go right on up. We’ll meet there.”

Selby said, “Okay, Rex,” hung up the telephone receiver and turned to his deputies. “You boys go to it,” he instructed.

“You’ll have to handle the routine business of the office.”

Grabbing his hat, Selby raced down the marble corridor of the courthouse, took the steps of the wide staircase two at a time, jumped into his car and drove to the Madison Hotel.

He noticed that Brandon was ahead of him. The sheriff’s car, equipped with red spotlight and siren, was parked in the red “no parking” zone in front of the hotel. Moreover, a portion of the street was closed off where a force of men were installing one of the new ornamental lighting fixtures the city had recently purchased. Selby found himself caught in a traffic jam and it took him nearly ten minutes to extricate himself, find a parking place for his car and return to the hotel.

George Cushing, owner of the hotel, and the one to whom Selby had been indebted for the room used as campaign headquarters, approached with smiling affability.

A man in his early fifties, Cushing tried to maintain an air of smart, urban sophistication. He wore a pin-striped blue serge suit, meticulously pressed, and cut on a style which obviously had been designed for men twenty years his junior.

His pale, filmed eyes had puffy circles beneath them. His wan skin looked as though it had never known the sting of a biting wind, nor the warm touch of outdoor sunlight.

But those pale, filmed eyes could be coldly insistent, and ten years of hotel management had taught him not to be backward in his demands.

“Now, listen, Doug,” he said, “this is just a natural death, see? It isn’t a suicide. The man took a dose of sleeping medicine, but that didn’t have anything to do with his death.”

“What’s his name?” the district attorney asked.

“The Reverend Charles Brower. He came from Millbank, Nevada. I don’t want it to be suicide. That gets unpleasant newspaper notoriety for the hotel.”

Walking toward the elevator Selby hoped that the man would at least have tact enough to refrain from referring to campaign obligations, but Cushing’s well-manicured, pudgy hand rested on the sleeve of Selby’s coat as the door of the elevator opened.

“You know,” Cushing said, “I did everything I could for you boys during the election, and I’d like to have you give me the breaks.”

Selby nodded.

Cushing said, “The number’s 321,” and waved to the elevator operator to close the door.

On the third floor, Selby found no difficulty in locating 321. He knocked on the panels, and Rex Brandon’s voice called, “Is that you, Doug?”

“Yes.”

“Go over to 323, Doug, and come in that way. That door’s unlocked.”

…

Selby walked to the adjoining room. It was a typical hotel bedroom. He saw that the connecting door into 321 was ajar. A long sliver had been smashed from the side of the doorjamb. Rex Brandon called, “Come on in, Doug.” Selby entered the room.

The little minister seemed strangely wistful as he lay cold and motionless on the bed. The eyes were closed and the jaw had sagged, but there was a smiling lift to the corners of the lips. The mantle of death had invested him with a dignity which his clerical garments had failed to achieve. The door had been locked and a chair propped against it in such a way that the back of the chair was braced directly underneath the knob of the door.

The room seemed filled with silence.

Otto Larkin, big, heavy-voiced chief of police, made haste to greet the district attorney.

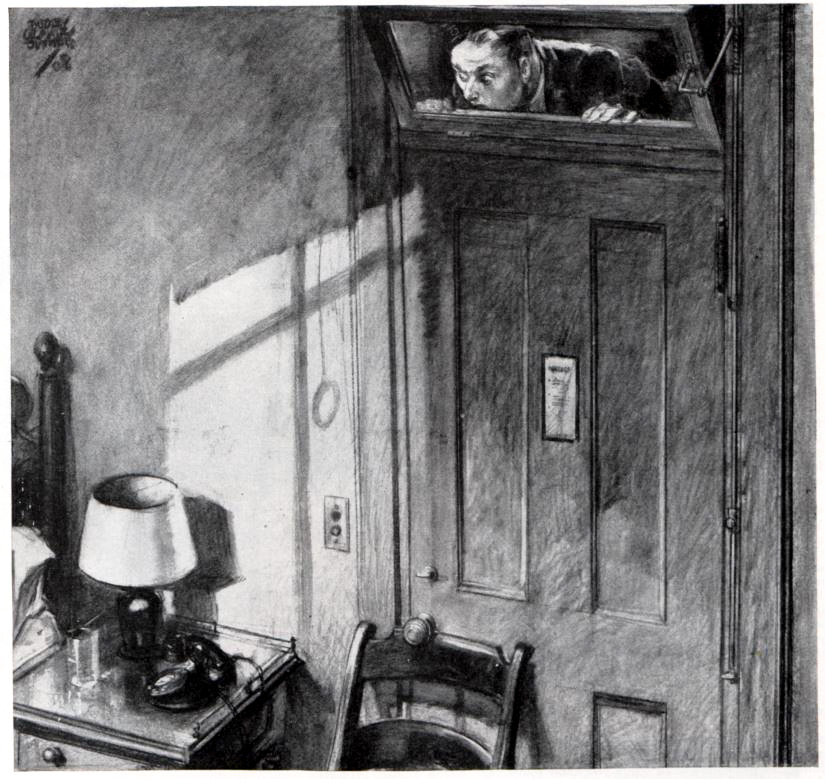

“Everything’s just as we found it,” he assured. “He’d left a call for ten o’clock. The switchboard operator rang and rang and didn’t get any answer. A bellboy knocked and heard nothing. He tried a passkey and found the door was bolted from the inside. He climbed up and looked through the transom. He could see the man lying on the bed. He called to him two or three times and then reached inside and pushed down the transom. Then he saw that a chair had been propped under the doorknob. He notified Cushing. Cushing busted in through 323. That’s why the lock’s smashed. The connecting door has a double bolt, one on each side.

“Now, listen, Selby, I was pretty friendly with Sam Roper, and I supported him in the campaign. But I want to work with you boys now you’re in office. This is the first case we’ve had, so let’s not have any hard feelings that’ll keep us from working in harmony.”

Selby said, “All right. What’s that paper in the typewriter? It isn’t a suicide note, is it?”

“No,” Brandon said, “it’s a letter to his wife, Doug.”

The district attorney leaned over the machine and read:

My dearest wife: Well, I’ve been in Madison City a couple of days now, and so far haven’t accomplished much. I may be here another week, perhaps longer.

The weather has been perfect. A fine warm sun blazing down from a deep blue sky, windless days and cool nights.

I’ll have a surprise for you when I come back. If I can contact just the right people, we’re going to have our financial troubles completely eliminated. And don’t think they won’t listen to me. They’ll have to listen. I wasn’t born yesterday, you know.

I didn’t sleep well on the train. I had some sleeping medicine to take, but it didn’t do much good, so tonight I took a double dose. I think I’m going to sleep fine. In fact, I’m sleepy right now.

This is a busy little city, with a streetcar line and several nice hotels. It’s less than a hundred miles from Hollywood, and I am going to go there before I get back, if I can spare the time. I’m sorry you can’t be here with me. I’m getting pretty sleepy now. I think I’ll go to bed and finish this in the morning. I’m awfully sleepy, dear. I’ll have a nice rest tonight. I’m going to leave a call for ten o’clock in the morning. Tomorrow I’ll look around some more … No use, I’m too sleepy to see the keyboard now.

There followed a word which had been crossed out by x’s.

On the table near the typewriter was an envelope addressed to “Mrs. Chas. Brower, 613 Center Street, Millbank, Nevada.”

“Looks as though he took an overdose of the sleeping medicine,” Rex Brandon said. “We’ve checked up on the hotel register. He filled out a card when he checked in. He’s Charles Brower and he comes from Millbank, Nevada. He lives at 613 Center Street, the address on the envelope. So everything checks okay. The poor chap wanted to sleep … Well, he’s sleeping all right.”

Selby nodded. “Why do you suppose he locked the door and then propped a chair against it?” he asked. “

“You can search me,” Brandon answered.

“Have you notified the coroner?” Selby asked.

“Yeah, sure. He’s out on a funeral right now. We expect him in any minute.”

“Look through his things?” Selby asked of Brandon.

“Not yet. We were sort of waiting for the coroner.”

“I’ve been on lots of cases with Harry Perkins, the coroner,” Larkin said. “He ain’t a bit fussy about red tape. If we want to save time by taking a look through things, it’ll be all right with Harry. As a matter of fact, I don’t think there’s anything to it. He probably had a bum ticker and taking a double dose of sleeping medicine put him out.”

“I was wondering,” Selby said, “if perhaps he had something very valuable he was trying to guard. I still can’t see why he should have gone to all that trouble to lock the door and then prop the chair against it.”

Walking over to the bed, Selby gently turned back the bedclothes and said, “No sign of any foul play. Well, I guess it’s just a routine matter. We’ll notify his wife.”

“I told George Cushing to send the wife a wire,” Sheriff Brandon said.

The chief of police frowned slightly. “I’m sorry you did that, Sheriff. That’s one of the things the coroner likes to do. You know, he’s an undertaker, and he usually mentions in his telegrams that he can prepare the body for burial,”

The sheriff drawled, “Harry was out on a funeral and I wanted to get some action. He can send her a wire when he comes in, if he wants to.”

Selby looked around the room.

The dead man’s coat and vest were in the closet, carefully placed on a hanger. The trousers had been caught by the cuffs in the top of the bureau drawer, and hung down almost to the floor. A single suitcase was on the chair, open.

“That his only baggage,” Selby asked — “a suitcase and a portable typewriter?”

“There’s an overcoat and a brief case in the closet,” Brandon said.

“What’s in the brief case?” Selby asked.

“Just some newspaper clippings and some typewritten stuff; either a sermon or a story or something — a lot of words slung together.”

The suitcase, Selby found, was packed with scrupulous care. The garments were neatly folded. He noticed two clean shirts, some light underwear, several starched collars, a leather-backed and worn Bible, a pair of spectacles in a case bearing the imprint of a San Francisco optician, and half a dozen pairs of plain black socks. He saw an oblong pasteboard medicine box with a label on which had been written in pen and ink, “For Restlessness.” There was also a leather case containing an expensive, foreign-made miniature camera.

“Hello,” Selby said, “this is a pretty good outfit for a small-town minister to be sporting. They cost about a hundred and fifty dollars.”

“Lots of people like this guy was are camera fiends,” the chief of police pointed out. “A man has to have some hobby, you know. Heaven knows, his clothes are shiny enough, and the overcoat’s badly worn at the elbows.”

“Where was his wallet?” Selby asked.

“In his coat pocket,” Brandon said.

“Any cards?”

“Yes, a few printed cards bearing the name, ‘Charles Brower, D.D., Millbank, Nevada,’ ninety-six dollars in cash, and about two dollars in small silver. There’s also a driving license.”

Selby looked once more at the still figure on the bed.

Somehow, a feeling of indecency gripped him. The man had been a human being; had had his hopes, fears, ambitions, disappointments, and now Selby was prying into his private life.

“All right,” he said, “I guess there’s nothing to it. Have the coroner take charge. He’ll probably want an inquest. By the way, George Cushing would appreciate it if there wasn’t any publicity and no talk of suicide.”

He turned away toward the door of 321, noticed the splintered casing where the bolt had been forced, and said casually, What’s the room on the other side, Rex?”

“I suppose the same as this,” the sheriff remarked.

“I think it has a bath,” the chief of police volunteered. “The way the hotel is laid out, there’s a bath in between rooms, and the room can be rented either with or without a bath. This room didn’t have the bath connected with it, so the bath’s probably connected with the other room.”

Selby idly inspected the knurled knob on the door which led to the shut-off bathroom. He twisted the knob and said, “Let’s see if this door’s open on the other side.”

Suddenly he frowned, and said, “Wait a minute. This door wasn’t bolted. Did someone twist this knob?”

“I don’t think so,” Larkin said. “The bellboy reported to Cushing, and Cushing told everyone nothing in the room was to be touched.”

“Then why didn’t Cushing get in through 319? He could have unlocked the door from the other side and wouldn’t have had to force the other one open.”

“I think that room’s occupied,” Larkin said. “Cushing told me 323 was vacant, but someone’s in 319.”

A knock sounded on the door of 321. Brandon called out, “Who is it?”

“Harry Perkins, the coroner.”

“Go around to 323, Harry, and come in that way.”

A moment later the tall figure of the bony-faced coroner came through the connecting door.

Larkin made explanations.

“We were just looking around a bit, Harry. You were out on a funeral, and we wanted to make sure what it was. It’s just a combination of an overdose of sleeping medicine and a bum pump. There won’t be enough of an estate to bother with. The sheriff wired his wife. Perhaps you’d better send her another wire and ask her if she wants you to take charge.”

The sheriff said, “I’m sorry, Harry, I didn’t know you liked to send those wires yourself.”

“That’s all right,” the coroner said. He walked over to the bed, looked down at the still form with a professional air and asked, “When do I move him?”

“Any time,” Larkin said. “Ain’t that right, Sheriff?”

Brandon nodded.

“I’m going back to the office,” Selby said.

III

Douglas Selby cleaned up the more urgent correspondence on his desk, went to a picture show, lay in bed and read a detective story. Reading the mystery yarn, he suddenly realized that it held a personal message for him.

Murder had ceased to be an impersonal matter of technique by which a writer used a corpse merely to serve as a peg on which to hang a mystery. Somehow, the quiet form of the wistful little minister lying in the hotel bedroom pushed its way into his mind, dominated his thoughts.

Selby closed the book with a slap. Why, he thought, was the little minister insidiously dominant in death? In life, the man, with his painfully precise habits, quiet, self-effacing, almost apologetic manner, would never have given Selby any mental reaction other than, perhaps, an amused curiosity.

Selby knew he had gone into the district-attorneyship battle primarily because of the fight involved. It had not been because he wanted to be district attorney. It was most certainly not because he wanted the salary. He had, of course, as a citizen, noticed certain signs of corruption in the preceding administration. Nothing had ever been proved against Sam Roper; but plenty had been surmised. There had been ugly rumors, which had been gradually magnified until the time had become ripe for someone to come forward and lead the fight. And the fact that Selby had been the one to lead that fight was caused more by a desire to do battle than by any wish to better the county administration.

Selby switched out the light, but the thought of what he had seen in that hotel bedroom persisted in his mind.

He tried to sleep and couldn’t, and even his futile attempt at slumber reminded him of the apologetic little man who had sought to woo sleep with a sedative. At twelve-thirty he put his pride to one side and called Rex Brandon on the telephone.

“Rex,” he said, “you’re probably going to laugh at me, but I can’t sleep.”

“What’s the matter, Doug?”

“I can’t get over that minister.”

“What about him, Doug; what’s the matter?”

“I can’t understand why he should have barricaded the door from the corridor, yet neglected to turn the knob in the door which communicated with the bathroom of 319.”

Brandon’s voice sounded incredulous. “For heaven’s sake, Doug, are you really worrying about that, or are you kidding me?”

“No, I’m serious.”

“Why, forget it. The man died from an overdose of sleeping medicine. The stuff he was taking was in that pasteboard box.”

“But why did he barricade his door as well as lock it?”

“He was nervous.”

“But that business of the pants being held in place in the bureau drawer,” Douglas persisted. “That’s an old trick of the veteran traveling salesman. No man who’d get nervous when he was away from home would do that.”

The sheriff said, “The man’s wife called up the coroner this afternoon. She’s coming on by plane. She told Perkins, Brower carried five thousand in insurance, and she seems to want to collect that in a hurry. She’s due here in the morning. She’s a second wife, married to him less than two years. His first wife died three or four years ago. Mrs. Brower said he’d had a nervous breakdown and the doctor advised a complete rest, so Brower took his flivver and started camping. He’d been raising money for a new church and had around five thousand dollars, but it had been too much of a strain on him. She thinks he must have had some mental trouble, to wind up here. So that shows everything’s okay. He took that sleeping medicine because he’d been nervous. There’s nothing to it.”

Selby laughed apologetically and said, “I guess it’s because we saw him in the hotel when he rode down in the elevator with us. Somehow, I couldn’t get over the feeling that if there had been … Well, you know what I mean, Rex — Oh, well, forget it. I’m sorry I bothered you.”

The sheriff laughed and said, “Better take two or three days and go fishing yourself, Doug. That campaign was pretty strenuous for a young chap like you.”

Selby laughed, dropped the receiver back on the hook and then fought with sleep for an hour. This sleep finally merged into a dead stupor, from which Selby emerged to grope mechanically for the jangling telephone.

It was broad daylight. Birds were singing in the trees. The sun was streaming through his windows, dazzling his sleep-swollen eyes. He put the receiver to his ear, said, “Hello,” and heard Rex Brandon’s voice, sounding curiously strained.

“Doug,” he said, “something’s gone wrong. I wonder if you can get over to your office right away?”

Selby flashed a glance at the electric clock in his bedroom. The hour was 8:30. He strove to keep the sleep out of his voice. “Certainly,” he said, making his tone crisply efficient.

“We’ll be waiting for you,” Brandon said, and hung up.

Selby reached his office on the stroke of nine.

Amorette Standish, his secretary, said, “The sheriff and a woman are in your private office.”

He nodded. Entering his private office, his eyes focused immediately upon a matronly, broad-hipped, ample-breasted woman of some fifty years, whose gloved hands were folded on her lap. Her eyes surveyed him with a certain quiet capability. There was the calm of cold determination about her.

Rex said, “This is Mary Brower, from Millbank, Nevada.”

Selby bowed and said, “It’s too bad about your husband, Mrs. Brower. It must have come as very much of a shock to you. I’m sorry there wasn’t any way we could have broken the news gently … ”

“But he wasn’t my husband,” the woman interrupted, with the simple finality of one announcing a very definite and self-evident fact.

“Then you have come here from Nevada because of a mistake?” Selby asked. “That certainly is … ”

He stopped mid-sentence. “Good Lord,” he said, and sat down in the swivel chair beside his desk to stare dazedly from the woman to Rex Brandon.

“You see,” the sheriff explained, “he had cards and a driving license in his wallet, and there was a letter he’d started to write to you, so we thought, of course, he was Charles Brower.”

“He isn’t my husband,” the woman insisted in the same tone of dogged finality. “I never saw him in my life.”

“But,” Selby pointed out, his mind groping through a sudden maze of contradictory facts, “why should he have written you if … How did he sign the register in the hotel, Rex?”

“As Reverend Charles Brower, 613 Center Street, Millbank, Nevada.”

Selby reached for his hat. “Come on, Rex,” he said. “We’re going down to get to the bottom of this thing.”

The woman in the faded brown suit with brown gloved hands still folded upon her lap, said, with dogged determination: “He is not my husband. Who’s going to pay my traveling expenses from Nevada here? Don’t think I’ll quietly turn around and go home without getting paid my carfare, because I won’t. I suppose I really could make serious trouble, you know. It was a great shock to me.”

IV

A trimly efficient young woman clad in a serviceable tailored suit sat waiting in the outer office as Selby started out.

“Hello, Sylvia,” he said. “Did you want to see me?”

“Yes.”

“I’m frightfully busy right now. I’ll see you sometime this afternoon.”

“Sometime this afternoon won’t do,” she told him.

“Why not?”

Her laughing, reddish-brown eyes smiled up at him, but there was a touch of determination about her jaw. “You are now talking,” she said, “to Miss Sylvia Martin, a reporter on The Clarion, who has been ordered to get an interview, or else.”

“But can’t it wait, Sylvia?”

“Not a chance,” she told him.

“But, hang it, it’ll have to wait.”

She turned resignedly toward the door and said, “Oh, all right, if that’s your attitude, of course I’m not running the paper. My boss sent me out to get this interview, and he said it was vitally important; that if you wouldn’t co-operate with us … Well, you know how he is. If you want to antagonize him, it’s all right with me.”

The sheriff frowned at Selby and said, “Of course, Doug, I could start investigating this thing and … ”

Selby turned back toward his office and said, “Okay, come on in, Sylvia.”

She laughed when the door of his private office had clicked shut behind them. “Forgive me for lying, Doug?” she asked.

“About what?”

“About being sent to get an interview.”

“Weren’t you?”

“No, I was just playing a hunch.”

His face showed swift annoyance.

“Now don’t be like that,” she told him, “because it isn’t nice. Don’t take the duties of your office too seriously.”

“Snap out of it, Sylvia,” he told her. “Just what are you trying to do? I’m working on an important case, and you’ve thrown me off my stride.”

She crossed her knees, smoothed her skirt, produced a notebook and pencil and started making intricate little patterns on the upper left-hand corner of the page. “You know, Doug,” she said, “The Clarion supported you in the campaign. The Blade fought you. We want the breaks.”

“You’ll get them as soon as there are any breaks.”

“How about this minister’s wife?” she asked. “I’ve heard she won’t identify the body.”

“Well,” he asked, “what of it?”

Her eyes rested steadily on his. “Doug,” she said slowly, “you know what an awful thing it would be, if some important case turned up right at the start and you muffed it.”

He nodded. “What makes you think I’m muffing it, Sylvia?”

“Call it womanly intuition, if you want. You know how hard I worked for you during the campaign, and how proud I am you’re elected. I … ”

He laughed, and said, “Okay, Sylvia, you win. Here’s the low-down. That woman was Mrs. Mary Brower, of Millbank, Nevada, and she says the body isn’t that of her husband. And she’s inclined to be peeved about everything.”

“Where does that leave you?” she asked.

“Frankly,” he told her, “I don’t know.”

“But didn’t the dead man have a letter in his typewriter plainly addressed to his dear wife? And wasn’t the envelope addressed to Mrs. Charles Brower at Millbank?”

“That’s right,” Doug admitted.

“And what does that mean?”

“It might mean either one of two things,” Selby said slowly. “If the man who registered as Brower wanted to impress some visitor that he really was Brower, it would have been quite natural for him to write this letter and leave it in the typewriter as a part of the deception. Then he might have left the room for a moment, figuring his visitor would read the letter while he was gone.”

Sylvia Martin nodded her head slowly and said, “Yes, that’s right. Let me see if I can guess the other alternative, Doug.”

She held up her hand for silence, frowned at him in thoughtful concentration for a moment, then suddenly exclaimed, “I’ve got it.”

“What is it?”

“If someone was in the room after the man had died and wanted to make it appear the cause of death was an overdose of sleeping medicine, he couldn’t have hit on a better scheme than to write a letter like that and leave it in the typewriter.”

“Exactly,” Selby interrupted. “Thank heavens, you agree with me on that. It seemed such a bizarre theory that I couldn’t even entertain it.”

“But, if that’s true,” she pointed out, “the man who wrote the letter must have known the wife. Otherwise, he couldn’t have known the street address.”

Selby said, “No, the man could have gotten the address from the hotel registrations. However, supposing he didn’t, let’s now take a look at Mary Brower, a matronly, capable woman who certainly wouldn’t be cavorting around with people who’d want to murder her husband. She’s obstinate, perhaps a bit selfish, but certainly no Cleopatra.”

Sylvia Martin was staring at him with wide, fascinated eyes. “But let’s suppose you’re wrong, Doug. Suppose someone did know her rather well and wanted her husband out of the way. Suppose this dead man sensed something of the situation and was a close friend of the husband. The husband didn’t know anything at all about what was going on, so this friend came to the hotel to take the part of the husband, and in order to do so masqueraded as Charles Brower.”

Selby said slowly, “That’s a nice theory, Sylvia, and if you publish any part of it, your newspaper will be defendant in about a dozen libel suits. This Mrs. Brower looks like a perfectly capable woman.”

Sylvia left her chair and came to stand by his desk.

“Listen, Doug,” she said, “my boss got a straight tip that The Blade is laying for you on this case. Don’t muff it, Doug. Keep your head and outsmart them.”

“You mean The Blade knows something?” Selby asked.

“I don’t know what they know, but we’ve got a tip they’re going to stir up some trouble about this case. You know Otto Larkin, the chief of police, is friendly with the managing editor. I think Larkin would double-cross you in a minute, if he had a chance. Any stuff The Blade has must have come from him.”

“Larkin isn’t any Sherlock Holmes,” Selby pointed out.

“Just the same,” she said, “I’ve given you the tip. Tell me, Doug, will you let me know if anything new develops?”

“I won’t release any information for publication until I’m satisfied it won’t hamper a solution of the case,” he said slowly.

“But can’t you just talk things over with me, not for publication, and let me have something to say about whether it’s safe to publish them?”

“Well,” Selby told her, “we might do that.”

She closed her notebook and said, “It’s definite, then, that this Mrs. Brower insists the man is not her husband?”

He nodded.

“And,” she asked him slowly, “how do you know that this woman is Mrs. Brower?”

He eyed her speculatively for a moment and said, “Now that’s a thought.”

“I think,” she told him, “we can find out from our Nevada correspondents.”

“And I,” he told her, “will also do a little investigating.”

He saw her to the door, then said to Amorette Standish, “Take a wire to the chief of police at Millbank, Nevada, asking him for a description of the Reverend Charles Brower and of Mary Brower his wife. Also find out if he knows where both of them are at present. Tell him to wire.”

V

Selby strode into the coroner’s office and said, “Harry, I want to go over everything you took from that minister’s room.”

“The stuff is sealed up and in this room over here,” the coroner told him. “Funny thing about putting a wrong tag on him, wasn’t it? What a sweet spot I’d have been in, if I’d sent the body by express to Nevada.”

Selby said, “Well, either he wasn’t Charles Brower, or she isn’t Mary Brower. She looks genuine. You get Doctor Trueman to make an examination. And I want a thorough examination made. Have the contents of the stomach analyzed and analyze all of the vital organs to find traces of poison.”

“You don’t think it’s anything like that, do you?” the coroner protested.

“I don’t know what I think. I’m going to find out when I’ve got something to think on.”

“Aw, shucks, it’s just a case of mistaken identity. It’ll be all straightened out within another twenty-four hours.”

“Nevertheless,” Selby said, “I want to know just how the man died.”

He took the suitcase, the portable typewriter and the brief case which the coroner handed him.

Selby said, “I think you’d better sit in here with me, Harry, and make a list of all this stuff.”

“I’ve already listed it,” the coroner replied.

“How did you describe it?”

“Personal papers, newspaper clippings, and such stuff.”

“I think we’d better make a more detailed list.”

He sat down in the chair, cut the sealed tape, opened the brief case and took out a number of papers from the leather pockets. He started sorting the newspaper clippings.

“Here’s one of Shirley Arden, the motion-picture star,” he said, “showing her in her new play, Mended Hearts. Here’s another one of her in a ‘still’ taken during the filming of that picture. Here’s one of her in Page the Groom. Here’s some publicity about her from one of the motion-picture fan magazines. Why all the crush on Shirley Arden, Harry?”

The coroner said, “That’s nothing. We see that every day. Almost everyone has some favorite motion-picture star. People collect all sorts of stuff. You remember this chap said in his letter that he might go on to Hollywood? I’ll bet you he’s gone on Shirley Arden, and was hoping he’d have a chance to meet her.”

The district attorney, forced to accept the logic of the remark, nodded, turned to the rest of the papers.

“Hello,” he said, “here’s some newspaper clippings about the Perry estate.”

“I was wondering about that, too,” the coroner said. “I just took a quick look through them. That’s the Perry estate that’s being fought over in our Superior Court, isn’t it? It says the man who’s trying to prove he’s the heir is H.F. Perry. That’ll be Herbert Perry, won’t it?”

Selby read through the clippings and nodded.

“They aren’t clippings from our papers, are they?”.

“No. They’re Associated Press dispatches, sent out to a number of papers which subscribe for that service.”

“Why do you suppose he saved them?”

“That’s one of the things we’re going to find out.”

“What are they fighting about in that case, anyway?”

“Charles Perry,” Selby said, “was married and got an interlocutory decree of divorce. Then, before the final decree was issued, he went over to Yuma, and married an Edith Fontaine. At the time of the marriage she had a son, Herbert. Herbert took the name of Perry, but Charles Perry wasn’t his father. The marriage, having been performed while an interlocutory decree was in effect, and before a final decree had been entered, was void. That was years ago. Apparently Perry never knew his marriage wasn’t legal. His first wife died, but he never had another marriage ceremony with Edith. He died without a will, and his brother, H. Franklin Perry, is contesting Herbert Perry’s share in the estate.”

“Isn’t there some law about marriage not being necessary where people live openly as man and wife?”

“That’s a common-law marriage.” Selby said. “It doesn’t apply in this state.”

“Well, Perry thought he was married to her all right. He died first, didn’t he?”

“Yes, they were in an automobile accident. He was killed instantly. She lived for a week with a fractured skull and died.”

“So the boy doesn’t get any of the money?” Perkins asked. “I know the brother. He’s a veterinary. He treated my dog once. He’s a good man.”

“Who gets the money is something for the courts to decide,” Selby said. “What I’m wondering about right now is what interested Charles Brower in that particular case.”

“Do you think he was Brower?”

“No, Harry, I don’t. I’m just calling him that because I don’t know anything else to call him.”

Selby looked through other clippings. One of them, from a fan magazine, listed the motion-picture actors and actresses in the order of their popularity. Another one gave what purported to be a tabulation of the gross earnings of the various stars during the preceding year.

A second pocket in the brief case contained a sheaf of typewritten papers. Evidently the typewriting had been done on the minister’s portable typewriter. It was a ragged job filled with crossed-out words and strike-overs. The district attorney noticed that at the top of page 1 appeared a title reading, “Lest Ye Be Judged.”

There followed a story written in a laborious, pedantic style. Selby started to wade through the story. It was the story of an old, irascible judge, entirely out of sympathy with the youth of the day, who had passed a harsh judgment upon a delinquent girl who had come before him. The judgment had been entirely without understanding and without mercy. The girl, declared to be an incorrigible, had been sentenced to a reformatory, but friends rallied to her support, led by a man whose status was not entirely clear. He was referred to as a lover of humanity.

The district attorney, searching the manuscript for some clue which would indicate this man’s love might have had a more personal focal point, became lost in a maze of pointless writing. He finally gathered that the man was much older; that his love was, in fact, really impersonal. The girl had taken up the study of medicine in the second chapter and had become a noted surgeon before the end of the chapter.

In chapter three the judge’s granddaughter, suffering with a brain tumor, was taken to the “greatest specialist in the world,” and when the judge, tears streaming down his face, called to plead with the surgeon to do his best, he found that the surgeon was none other than the girl he had sentenced as an incorrigible.

There were several pages of psychological explanations, the general purport of which was that the girl had been filled with a certain excess of vitality, a certain animal energy which required a definite ambition upon which to concentrate. The man who had saved her had been shrewd enough to place her in school and to dare her to accomplish the impossible. The very difficulty of the task had served to steady her.

“What’s it about?” the coroner asked, when the district attorney had turned over the last page.

“It’s a proof of the old axiom,” Selby said, grinning, “that there lives no man with soul so dead who hasn’t tried to write a picture scenario.”

“That what it is?”

“That’s what it was probably intended to be.”

“I’ll bet you he figured on going down to Hollywood to peddle that scenario.”

“If he did,” Selby pointed out, “he certainly made a peculiar detour. He was sneaking into Hollywood by the back way.”

There were no further papers in the brief case. The district attorney closed it and the coroner taped and sealed it.

Once more Selby went into the suitcase.

“There aren’t any laundry marks on any of those clothes,” the coroner said. “Not even on his starched collars. Ain’t that a little peculiar?”

Selby nodded.

“Probably the first trip he’d made with these clothes,” he said, “or he’d have had them laundered somewhere. And he couldn’t have been away from home very long. Also, he must have a very efficient wife who’s a hard-working housekeeper. That all indicates a ministerial background.”

Selby inspected the small pasteboard box containing a long roll of paper in which five-grain tablets had been folded.

“This the sedative?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“And one of these tablets wouldn’t have brought about death?”

“Not a chance,” the coroner said. “I’ve known people to take four of them.”

“What did cause death then?”

“Probably a bad heart. A double dose of this stuff might have helped bring on the heart attack.”

“You have Doctor Trueman check carefully on that heart attack,” Selby instructed. “I want to know, absolutely, what caused this man’s death.”

The coroner fidgeted uneasily, finally said, “I wonder if you’d mind if I gave you a little advice, Douglas.”

“Go ahead, Harry, dish it out,” Selby said with a smile, “and I’ll try and take it.”

“This is your first case,” the coroner said. “You seem to be trying to make a murder case out of it. Now I wouldn’t go putting the cart before the horse. There’s a lot of sentiment against you in this county, and a lot of it for you. The people who are for you put you in office. The people who are against you hate to have you in office. You go along without attracting any great amount of attention for a month or two, and pretty quick people will forget all about the political end of things. Then those who hated you will be smiling and shaking hands when they see you on the street. But you get off on the wrong foot, and it’s going to hurt. Your enemies will be tickled to death and you’ll lose some of your friends.”

Selby said, “Harry, I don’t care how this thing looks to you. I’m not satisfied with it.”

“You get to looking at dead people through a microscope and you’ll never be satisfied with anything,” the coroner objected. “Things never do check out in real life. This guy was registered under a phony name. Nothing to get excited about in that — lots of people do it.”

Selby shook his head and laid down what was to be his primary code of conduct during his term of office.

“Harry,” he said, “facts fit. They’re like figures. If you get all the facts, your debit column adds up the same as your credit column. The facts balance with the result and the result balances with the facts. Any time they don’t, it’s because we haven’t all of the facts, and are trying to force a balance with the wrong figures. Now take that typewritten letter, for instance. It wasn’t written by the same man who wrote the scenario. The typing in the letter is perfect, evenly matched and free of strike-overs. The scenario is a hunt-and-peck affair, sloppy and ragged. Probably they were both written on the same machine, but they weren’t written by the same person. That’s an illustration of what I mean by saying that facts must balance, if they’re going to support theories.”

The coroner sighed. “Well, I told you, anyhow,” he remarked. “Go ahead and make a murder out of it, if you want to. You’ll find it’ll be a boomerang.”

Selby grinned, thanked him, left the mortuary and went at once to the Madison Hotel.

In the manager’s private office Selby had a showdown with George Cushing.

“Otto Larkin,” Cushing said reproachfully, “tells me you’re making a mountain out of a molehill on this Brower case, Selby. I didn’t think you’d do that to me.”

“I’m not doing it to you, George.”

“Well, you’re doing it to my business.”

“I’m not doing anything to your business. I’m going to find out the facts in this case, that’s all.”

“You’ve already got the facts.”

“No, I haven’t. The facts I’ve had have been wrong. The man isn’t Charles Brower.”

“Oh, that,” Cushing said, with a wave of his hand. “That frequently happens. Lots of people register under assumed names for one reason or another, and sometimes, if people happen to have a friend’s card in their pockets, they’ll register under the name of the friend, figuring they can produce the card, if anyone questions them.”

“Whom did this man know in the hotel?” the district attorney asked.

Cushing raised his eyebrows. “In the hotel?” he asked. “Why, I don’t suppose he knew anyone.” “Whom did he know in town?”

“I couldn’t tell you about that. No one that I know of. A man who hadn’t done much traveling and came here from Millbank, Nevada, wouldn’t be apt to know anyone here in the hotel or in the town either.”

“When Sheriff Brandon and I were coming out of campaign headquarters on the fifth floor the other morning,” Selby said, “this preacher was coming out of a room on the fifth floor. It was a room on the right-hand side of the corridor, and I’d say it was somewhere between 507 and 519.”

Cushing’s face showed emotion. He leaned forward. His breathing was distinctly audible.

“Now listen, Doug,” he said, “why not lay off of this thing? You’re not doing the hotel any good and you’re not doing yourself any good.”

“I’m going to find out who this man is and I’m going to find out how he died and why he died,” Selby said doggedly.

“He’s some bird from Millbank, Nevada, or some nearby place,” Cushing said. “He knows this man Brower in Millbank. He knew Brower was away on a fishing trip, so he figured it would be a good time to use Brower’s name.”

“Who occupied those rooms on the fifth floor?” Selby insisted.

“I’m sure I couldn’t tell you.”

“Get your register.”

“Now, listen, Doug, you’re carrying this thing too far.”

The district attorney said, “Get the register, George.”

Cushing got up, started for the door, hesitated for a moment, then came back and sat down.

“Well,” Selby said, “go ahead, get the register.”

“There’s something about this,” Cushing said slowly, “that I don’t want made public. It doesn’t concern this case in any way.”

“What is it?”

“It’s something that won’t be shown by the register, but you’ll probably find out about it, if you get to nosing around … And,” he added bitterly, “it looks like you’re going to nose around.”

“I am,” Selby promised.

“There was a guest here Monday who didn’t want her identity known.”

“What room was she in?”

“Five-fifteen.”

“Who was she?”

“I can’t tell you that, Doug. It hasn’t anything to do with the case.”

“Why don’t you want to tell me then?”

“Because she came here on business. It was rather a confidential business. She was trying to keep it from becoming known. She signed a fictitious name on the register and made me agree I’d say nothing about her having been here. She only stayed a couple of hours and then went back. Her manager, I think, stayed on a little longer.”

“Who was she?”

“I can’t tell you. She’s famous and she didn’t want the newspapers making a lot of hullabaloo about her. I don’t want her to think I’ve broken my promise. She comes here sometimes when she wants to get away from everything, and always has the same room. I sort of keep it for her … and … well, that’s why I’m telling you all this. I don’t want you stirring up any publicity about room 515.”

A sudden realization crystallized in Selby’s mind, a realization of something so weirdly bizarre that it didn’t make sense, yet was entirely on a par with the other developments in the case.

“That woman,” he said with the calm finality of one who is absolutely certain of his statements, “was Shirley Arden, the motion-picture actress.”

George Cushing’s eyes widened. “How the devil did you know?”

Selby said, “Never mind that. Tell me all you know.”

“Ben Trask, her manager and publicity agent, was with her. Miss Arden went in by way of the freight elevator. Trask saw that the coast was clear.”

“Did anyone in the hotel call on her?”

“I wouldn’t know.”

“Did Trask have a room here?”

“No.”

“What is this room, a bedroom?”

“It’s a suite; a bedroom, sitting room and bath.”

“Any outside telephone calls?” Selby asked.

“I wouldn’t know. I can find out by looking up the records.”

“Do that.”

Cushing fidgeted uneasily and said, “This preacher left an envelope in the safe. I had forgotten about it until this morning. Do you want me to get it?”

“What’s in it?”

“A letter or something.”

“Yes,” Selby said, “get it.”

“I’d like to have you sign for it.”

“All right, bring a receipt and I’ll sign.”

The hotel manager stepped from the office for a few moments, then returned with a sealed envelope, across the flap of which appeared a scrawled signature, “Charles Brower.”

“Wait here,” Selby told him, “while I open the envelope. We’ll list the contents.”

He slit the end of the envelope with a knife and pulled out several folded sheets of hotel stationery.

“Well,” he said, “this looks . . .”

His voice trailed into silence as his fingers unfolded the sheets of stationery. Five one-thousand-dollar bills had been folded between two sheets of hotel stationery.

“Good Lord!” Cushing exclaimed.

“You sure the minister put this envelope in the safe?” Selby asked.

“Yes.”

“No chance for any mistake?”

“None whatever.”

Selby turned the bills over in his fingers. Then, as a delicate scent was wafted to his nostrils, he raised the bills to his nose; Pushed them across the table and said to Cushing, “Smell.”

Cushing sniffed of the bills. “Perfume,” he said.

Selby folded the bills back in the paper and slipped both paper and bills back in the envelope.

“Take a strip of gummed paper,” he said. “Seal up that envelope and put it back in the safe. That’ll keep the odor of the perfume from being dissipated. I’ll want to check it later. . . Now, then, who had room 319?”

“When the body was discovered, a man by the name of Block was in the room.”

“Where’s he from? What does he do, and how long have you known him?”

“He’s a traveling salesman who works out of Los Angeles for one of the hardware firms.”

“Has he checked out yet?”

“I don’t think so, but he’s just about due to check out.”

“I want to talk with him.”

“I’ll see if he’s in.”

“Who had the room before Block?”

“I’ve looked that up. The room hadn’t been rented for three days.”

“The room on the other side — 323?”

“That was vacant when the body was discovered, but had been rented the night before to a young couple from Hollywood, a Mr. and Mrs. Leslie Smith.”

“Get their street number from the register. See if this salesman is in his room. I want to talk with him. Seal that envelope and put it back in the safe.”

Cushing excused himself, and this time was gone some five minutes. He returned, accompanied by a well-dressed man in the early thirties, whose manner radiated smiling self-assurance.

“This is Mr. Block, the man who’s in Room 319,” he said.

Block wasted no time in preliminaries. His face wreathed in a welcoming smile, he gripped Selby’s hand cordially.

“I’m very pleased to meet you, Mr. Selby. I understand you’re to be congratulated on winning one of the most bitterly contested elections ever held in the history of the county. I’ve been covering this territory several years, and I’ve heard everywhere about the splendid campaign you were putting up. My name’s Carl Block, and I’m with the Central Hardware Supplies Company. I come through here regularly once a month, making headquarters here for a couple of days, while I cover the outlying towns. Is there any way in which I can be of service to you?”

The man’s manner exuded a ready, rugged friendliness. Sizing him up, Selby knew why he held such a splendid sales record, knew also that it would be next to impossible to surprise any information from him.

“You got in yesterday morning, Mr. Block?”

“That’s right.”

“About what time?”

“Well, I got in pretty early. I find that these days the business comes to the man who goes after it.”

“Hear any unusual sounds from the adjoining room?”

“Not a sound.”

“Thank you,” Selby said, “that’s all.” He nodded to Cushing and said, “I’m going back to my office, George. Don’t give out any information.”

Cushing followed him to the door of the hotel. “Now, listen, Doug,” he said, “this thing was just a natural death. There’s no use getting worked up about it, and remember to keep that information about Miss Arden under your hat.”

VI

Selby said to Frank Gordon, “Frank, I want you to find out everything you can about the litigation in the Perry Estate.”

“I think I can tell you all about it,” Gordon said. “I know John Baggs, the attorney for Herbert Perry. He’s discussed the case with me.”

“What are the facts?”

“Charles Perry married Edith Fontaine in Yuma. The marriage wasn’t legal because Perry only had an interlocutory decree. He had the mistaken idea he could leave the state and make a good marriage. Edith Fontaine had a son by a previous marriage — Herbert Fontaine. He changed his name to Perry. Perry and his wife were killed in an auto accident. If there wasn’t any marriage, the property goes to H. Franklin Perry, the veterinary, a brother of Charles. If the marriage was legal, the bulk of the property vested in Edith on the death of Charles, and Herbert is Edith’s sole heir. That’s the case in a nutshell.”

“Who’s representing H. Franklin Perry?”

“Fred Lattaur.”

“Get a picture of the dead minister. See if either of the litigants can identify him.”

He picked up the phone and said to the exchange operator,” I want Sheriff Brandon, please. Then I want Shirley Arden, the picture actress.” In a moment he heard Rex Brandon’s voice.

“Just had an idea,” Selby said. “There was a pair of reading spectacles in that suitcase. Get an oculist here to get the prescription. Get a photograph of the dead man. Rush the photograph and the prescription to the optician in San Francisco whose name is on the spectacle case. Have him look through his records and see if he can identify the spectacles.”

“Okay,” Brandon said cheerfully. “I’m running down a couple of other clues. I’ll see you later on.”

Selby’s secretary reported, “Miss Arden is working on the set. She can’t come to the telephone. A Mr. Trask says he’ll take the call. He says he’s her manager.”

“Very well,” Selby said, “put Trask on the line.”

He heard a click, then a masculine voice saying suavely, “Yes, Mr. Selby?”

Selby snapped words into the transmitter. “I don’t want to say anything over the telephone which would embarrass you or Miss Arden,” he said. “Perhaps you know who I am.”

“Yes, I do, Mr. Selby.”

“Day before yesterday,” Selby said, “Miss Arden made a trip. You were with her.”

“Yes.”

“I want to question her about that trip.”

“But why?”

Selby said, “I think you’d prefer I didn’t answer that question over the telephone. I want to see both you and Miss Arden in my office sometime before nine o’clock tonight.”

“But, I say, that’s quite impossible,” Trask protested. “Miss Arden’s working on a picture and … ”

Selby interrupted. “I have ways,” he said, “of getting Miss Arden’s statement. There are hard ways and easy ways. This is the easy way — for you.”

There was a moment’s silence, then the voice said, “At ten o’clock tonight, Mr. Selby?”

“I’d prefer an earlier hour. How about seven or eight?”

“Eight o’clock would be the earliest time we could possibly make it. Miss Arden is under contract, and … ”

“Very well,” Selby said, “at eight o’clock tonight,” and hung up before the manager could think of additional excuse.

He had hardly hung up the telephone before it rang with shrill insistence. He took the receiver from the hook, said “Hello,” and heard the calmly professional voice of Dr. Ralph Trueman.

“You wanted information about that man who was found dead in the Madison Hotel,” Trueman said.

“Yes. What information have you?”

“I haven’t covered everything,” Doctor Trueman said, “but I’ve gone far enough to be morally certain of the cause of death.”

“What was it?”

“A lethal dose of morphine, taken internally.”

“Of morphine!” Selby exclaimed. “Why, the man had some sleeping tablets … ”

“Which hadn’t been taken at all, so far as I can ascertain,” Trueman interrupted. “But what he had taken was a terrific dose of morphine, which induced paralysis of the respiratory organs. Death probably took place between midnight and three o’clock yesterday morning.”

“And when was the morphine administered?”

“Any time from one to two hours prior to death.”

“How?”

“Well, I’m not certain about that,” Trueman said, “but there’s some chance a tablet containing the deadly dose might have been inserted in the box of sedative which the man was carrying with him. In that event he’d have taken the morphia, thinking he was taking an ordinary sleeping tablet. The tablets were wrapped in paper so that they’d naturally be taken in a consecutive order. I’ve made a very delicate test with some of the paper remaining in the box and get a definite trace of morphia.”

“Could that have been a possible error on the part of the druggist filling the prescription?” Selby asked.

“In a tablet of that size, with that amount of morphia,” Doctor Trueman said, “the chance of honest error would be just about one in ten million.”

“Then … then it was deliberate, carefully planned murder!” Selby said.

Doctor Trueman’s voice retained its professional calm. “That,” he observed, “is a matter of law. I’m merely giving you the medical facts.”

TO BE CONTINUED (READ PART II)

Featured image: Illustrated by Dudley Gloyne Summers.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

The next installment of the story will be published online next week. Please e-mail me at [email protected] if you would like the story sooner, since it can’t be found in our online archives.

Totally agree with Robert Sutton about Thread of Truth. The Country Gentleman only published what the Post did and left me hanging. I searched for a book by the title with no results. Please, where is the rest of the story?

The Thread of Truth end of first installment references Sept 1,1936 issue of Post. There is no such issue in your archives and link is to another

Mag with first installment only. Remainder of story please?>