When he died, in 1970, Erle Stanley Gardner was the best-selling American fiction author of the century. His detective stories sold all over the globe, especially those with his most famous defense attorney protagonist, Perry Mason. His no-nonsense prose and neat, satisfying endings delighted detective fans for decades. Gardner wrote several stories that were serialized in the Post. In Country Gentleman, his 1936 serial “The Thread of Truth” follows a fresh D.A. in a clergyman murder case that comes on his first day on the job.

Published on November 1, 1936

Who was the little minister found dead of poison in Room 321 of the Madison Hotel? He was registered as the Rev. Charles Brower, and in the portable typewriter on his desk was an unfinished letter to Mrs. Charles Brower, addressed, “My Dearest Wife” But Mrs. Brower, summoned from Nevada to Madison City to identify her husband, declared that she had never seen the man before.

Douglas Selby, district attorney of the small California city near Hollywood, knew that it was imperative for him to discover both the minister’s identity and his murderer. For The Blade, newspaper ally of Selby’s crooked predecessor, was eager to ruin the young newcomer if he failed in his first important case. The other newspaper, The Clarion, was friendly, particularly in the person of Sylvia Martin, lovely young reporter, but The Blade was powerful.

The mysterious preacher had scant possessions when he died, just a few threadbare clothes, an expensive camera, a pitiful movie scenario, clippings concerning the famous Shirley Arden of nearby Hollywood, and more clippings concerning litigation in Madison City courts over the Perry estate. With Rex Brandon, his faithful sheriff, Douglas Selby worked furiously on the meager clues. He discovered that Room 515 of the Madison Hotel, from which the minister had emerged the morning before the murder, was permanently reserved for the motion-picture star, Shirley Arden. George Cushing, hotel manager, was singularly reluctant to talk about his famous guest.

Selby forced an interview with Shirley Arden. She admitted having been visited by the minister, but flatly denied having given him the five one-thousand-dollar bills he had left in a rose-perfumed envelope in the hotel safe. She tried to remember the name the minister had given her, but could not recall it clearly. Then, turning on the full power of her trained emotions and perfect beauty, she pleaded with Selby for protection from harmful publicity. Selby, ascertaining that the perfume she used was not similar to that used in the five-thousand-dollar envelope, and suffused with her charm, was convinced of her innocence. He promised to shield her name.

Rumor spread through the town that the crack reporter of The Blade had uncovered some startling leads on the mystery and that The Blade was about to charge Selby with inefficiency in office. Then Rex Brandon telephoned that a San Francisco optician had identified the dead man’s spectacles as belonging to one of several people, among whom was a Reverend Larrabie of Riverbend. Selby tingled with excitement! That was the name Shirley Arden had been trying to remember! Hastily Selby prepared to take a plane to Riverbend. With him, flushed and delighted, went Sylvia Martin of The Clarion.

X

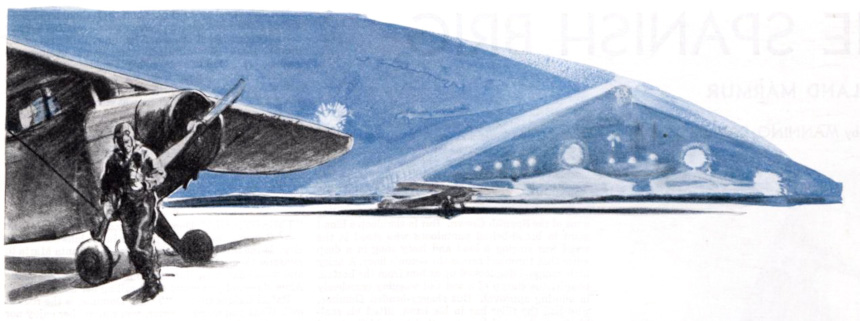

The plane, a small cabin ship, roared on through the darkness. The altimeter registered an elevation of six thousand feet. The clock on the dash showed the time as two-fifteen.

A cluster of lights showed vaguely ahead, looking as glimmeringly indistinct as a gaseous nebula seen through a telescope. Directly below, a beacon light flashed warning blinks of red, then white, as a long beam from its searchlight circled the country like some questing finger.

The pilot leaned toward Doug Selby, placed his lips close to the district attorney’s ear and shouted, “That’s Sacramento. I’ll land there. I won’t take chances on a night landing farther up. You’ll have to go on by car.”

“I’ve already arranged for the car,” Selby yelled.

Her face looking wan from the strain and excitement, Sylvia Martin slumped back in the cushioned seat, her eyes closed, her senses fatigued by the steady roar of the motor, which had beat a ceaseless pulsation upon her eardrums for more than two hours.

The lights of Sacramento steadily gained in brilliance, resolved themselves into myriad pin points of incandescence which winked and twinkled out of the darkness.

The plane swung slightly to the right as the pilot got his bearings. The streetlights came marching forward toward the plane in a steady procession. The pilot throttled down the motor, tilted the plane toward the ground.

As the steady pulsations gave way to a peculiar whining noise and the wind started to scream through the struts, Sylvia Martin woke up, smiled at Selby, leaned forward and shouted, “Where are we?”

The noise of the motor drowned out her words, but Selby guessed at her question, placed his lips close to her ear and yelled, “Sacramento.”

The plane tilted forward at a sharper angle, the lights rose up to meet them. An airport showed below. The pilot straightened out and gunned the motor. With the roar of sound, floodlights illuminated a landing runway. The pilot noted the direction of the wind from an illuminated wind sock, swung into position, once more cut down the motor, and came gliding toward the ground. The wheels struck the smooth runway. The plane gave a quick series of jolts, then rolled forward toward the buildings.

As the plane came to a stop, a man wearing an overcoat and a chauffeur’s cap came walking out toward it. The pilot opened the cabin door. Selby climbed stiffly to the ground, assisted Sylvia Martin to alight. The slip stream from the idling motor caught her skirts, blew them tightly about the shapely limbs, then whipped them upward. She gave a startled scream, grabbed at her skirts, and Selby swung her clear of the wind current.

She laughed nervously and, forgetting for the moment there was no longer need to shout against the roar of the motor, yelled at the top of her voice, “I didn’t know what to grab at first, my skirts or my hair.”

The man in the overcoat and chauffeur’s cap heard her, smiled, took off his cap and said, “Are you the parties who telephoned for the car — Mr. Selby?”

“Yes,” Selby said; “I want to go to Riverbend. How long will it take us to get there?”

“About three hours.”

Selby looked at his wrist watch and said, “All right, let’s go. Can we get some coffee here?”

“Sure, there’s a swell little restaurant where you can get almost anything you want.”

They had coffee and hamburger sandwiches at the lunch counter. Sylvia grinned across at the district attorney and said, “Adventure — eh, what?”

He nodded. His mood was as buoyant as her own. “Late hours for us country folk,” he told her.

“You know, there’s an exhilaration about riding in a plane,” she said, sighing.

“Your first time?” he asked.

“Yes. I was frightened to death, but I didn’t want to say so.”

“I thought so,” he told her.

“That bumpy air over the mountains made me think the plane had lost a wing and we were falling.”

“It was a bit rough for a minute. However, we’re here now. It won’t be long until we know the answer.”

Her eyes sparkled over the rim of her coffee cup at him.

“You know, Doug, I’m sorry I doubted you. It’s a swell break to give me. I can telephone in a story that will be a peach … I suppose he’s married … Oh, I shouldn’t be talking like this, but I’d be a hypocrite if I didn’t. After all, he’s dead and nothing I can do can call him back. Of course, I’m sorry that we’ll have to be the ones to break the news to his wife, and all of that, but I’m just enough of a news-hound to appreciate what a swell story it’ll be. I can pack it full of human emotion. The Blade may or may not uncover something about the man’s identity, but they can’t get in on the ground floor, telling just how the news was received. They can’t give an accurate word picture of the man’s background, his home and … Oh, dear, Doug, you don’t suppose there are kiddies, do you?”

“We don’t know a thing in the world about it,” he said. “We’re not even definitely certain he’s the man.”

“Tell me, Doug, how did you know the name had a ‘Larry’ in it, and that he lived in a place that was a River something-or-other?”

He shook his head, looked at his wrist watch and said, “Finish up your sandwich. You can ask questions later.”

She wolfed down the rest of the sandwich, washed it down with coffee, wiped her finger tips on the napkin, grinned and said, “‘Rotten manners,’ says Emily Post, but ‘Swell stuff,’ says the city editor. Come on, Doug, let’s go.”

For several moments she was depressed; then, walking across toward the waiting automobile, she regained some measure of her spirits.

“Somehow,” she said, “from the description we have of him, I don’t think there are children. If there are, they’ll be pretty well grown. Do you know what the population of Riverbend is, Doug?”

“No. It’s just a pin point on the map. I suppose it’s little more than a crossroads, although it may be fifteen hundred or two thousand.”

“We’ll get there,” she said, “just about daylight. It’ll be on a river, with willow trees growing along the banks. The place will look drab, just as dawn commences to break. There’ll be a church which is in need of paint, a parsonage in back of the church, a poor little house trying to put up a brave front … Tell me, Doug, why can’t they incorporate religion?”

“What do you mean?” he asked.

“Fix it so that the big-moneyed churches finance the little ones. You know as well as I do how hard it is to keep a minister going in a little town of five hundred to two thousand people. There are probably four or five denominations represented. Each of them wants its own church and its own minister.”

“You mean they should consolidate?”

“No, no, not the denominations, Doug, but I mean the big churches should support the little ones. For instance, suppose this man is a Methodist, and, say, in the big cities there are big, prosperous Methodist churches. Why couldn’t the big churches support the little ones?”

“Don’t they?” he asked. “Isn’t there an arrangement by which part of the man’s salary is paid? … ”

“Oh, I don’t mean that. I mean really support them. It seems a shame that the Methodists in Riverbend should support the Methodist Church in Riverbend, and the Methodists in San Francisco should support the Methodist Churches in San Francisco. Why can’t they all support churches everywhere?”

“You’ll have to take it up with the churches,” he told her. “Come on, get in.”

She laughed and said, “I think I’m getting sentimental, Doug.”

“You get over in that corner of the seat,” he ordered, “and go to sleep. You’re going to have a hard day.”

She pouted and said, “My head will jolt around on that corner of the seat.”

“Oh, all right,” he told her, laughing, and, sliding his arm about her shoulders, “come on over.”

She gave a sigh, snuggled down against his shoulder, and was asleep before the car had purred along the smooth ribbon of cement highway for more than a mile.

She wakened as the car slowed, rubbed her eyes and looked about her. The first streaks of dawn were shrinking the beams of the headlights into little insignificant threads of illumination. The stars had receded until they were barely visible. The tang of dawn was in the air. The countryside was taking on a gray, spectral appearance.

A few scattered houses gave place to a street fairly well built up with unpretentious residences. The car slowed almost to a stop, turned a corner, and Sylvia exclaimed, “Oh, goody, the main street! Look at The Emporium.”

“Where to?” the driver asked.

“I want to find the place where a Reverend Larrabie lived. I have a hunch he was a Methodist. Let’s see if we can find the Methodist Church. Or we may find some service station that’s open.”

“There’s one down the street,” the driver said.

They drove into the service station. A young man, his hair slightly tousled, emerged from the warm interior into the chill tang of the morning air. He fought against a yawn while he tried to smile.

Selby laughed, rolled down the window and said, “We’re looking for the Reverend Larrabie. Can you tell me where he lives?”

“Methodist parsonage, straight on down the road two blocks, turn to the left one block,” the young man said. “May I clean your windshield for you? And how’s the water in your radiator?”

The driver laughed and said, “You win, fill ’er up.”

They waited while the car was being serviced, then once more started on. By this time the sky was showing a bluish tint. Birds were timidly throating the first tentative notes of a new dawn. They rounded the corner to the left and saw a small white church building which, even in the dim light of early dawn, showed that it was sadly in need of paint. As the driver slid the car in close to the curb and stopped it, a dog began to bark. Aside from that, there was no sign of life in the street.

“Well,” the driver said, “here we are.”

He opened the door. Selby stepped out, gave his hand to Sylvia. They crossed a strip of unpaved sidewalk, opened a gate in a picket fence. The dog across the street began to bark hysterically.

Sylvia was looking about her, her eyes alight with interest, her cheeks flushed.

“Perfect!” she exclaimed. “Absolutely priceless!”

They walked up a little graveled walk, their heels crunching the pebbles, sounding absurdly loud in the hush of early morning. Doug Selby led the way up the wooden steps to the porch, crossed to the door and rang the bell. A faint jangling sound could be heard from the interior of the house. The district attorney opened the screen door and pounded with his knuckles on the panels of the door.

“Oh, there must be someone home. There simply has to be,” Sylvia said in a half whisper.

Once more Selby’s knuckles beat a tattoo on the panels of the door. Sylvia Martin pressed a gloved thumb against the bell button.

From within the house came the sounds of muffled footsteps.

Sylvia laughed nervously. “Doug,” she said, “I’m so excited I could burst!”

The footsteps approached the door. The knob turned, the door opened. A motherly woman, with hair which had just commenced to turn gray and was tousled about her head, a bathrobe wrapped about her, what was evidently a flannel nightgown showing through the opening in the neck of the robe, surveyed them with patient gray eyes.

All of the elation fled from Sylvia’s manner. “Oh, you poor thing,” she said in a half whisper which was vibrant with sympathy.

“What is it?” the woman asked.

“I’m looking for the Reverend Larrabie.”

“He isn’t here. I don’t expect him back for three or four days.”

“Are you Mrs. Larrabie?”

“Yes.”

“May we come in?” Selby asked.

She studied him with puzzled eyes and said, “What is it you want, young man?”

“I wanted to talk with you about your husband.”

“What about him?”

“Have you,” Selby asked, “a picture of him that I could see — some informal snapshot, perhaps?”

For a moment the eyes faltered, then they stared bravely at him.

“Has something happened to Will?” she asked.

“I think,” Sylvia Martin said impulsively, “it would be a lot better, Mrs. Larrabie, if you could let us make certain before we talk with you. We could tell if we saw a photograph.”

Selby held the screen door open. Sylvia Martin slipped through and put her arm about the older woman’s waist.

“Please don’t worry, dear,” she said, “there may be nothing to it.” Her lips were tightly held in a firm line as Mrs. Larrabie led the way into a front parlor, a room which was warm with the intimacies of living. A magazine lay face down on the table. Several periodicals were thrust into a magazine rack in the arm of a mission-type chair, evidently the product of home carpentering.

The woman pointed to a framed picture. “That’s him,” she said simply.

Selby looked, and knew at once he had come to the end of his quest.

“May we sit down?” he asked. “I’m afraid we’re bringing bad news for you, Mrs. Larrabie.”

“What’s happened?” she asked.

“Do you know where your husband is?” he inquired.

“I think he’s in Hollywood.”

“Do you know what he went there for?”

“No. What’s happened?”

“I’m afraid that …”

“Sick?” she asked in a calm, level voice.

“No,” Selby said, “ … not sick.”

“Dead?”

Selby nodded.

Not a muscle of her face quivered. Her mouth didn’t even twitch at the corners. But two tears welled into her motherly gray eyes, trickled unheeded down her cheeks.

“Tell me about it,” she requested, still in that calm, steady voice.

“I’m Douglas Selby, the district attorney of Madison City,” Selby explained. “That’s a city about sixty miles from Los Angeles.”

“Yes, I know where it is.”

“A minister came to the Madison Hotel and registered under the name of Charles Brower. He was found dead in his room. That was Tuesday morning. We’ve been trying to find out … ”

“Why, I know Charles Brower,” she said, her eyes widening. “If that’s the one who’s dead . . .”

“But it isn’t,” Selby explained, interrupting. “We thought that the man was Charles Brower because he registered as Charles Brower, of Millbank, Nevada.”

“That’s right, that’s where Mr. Brower lives.”

“We notified Millbank. Mrs. Brower came on and said that the body wasn’t that of her husband.”

“But it couldn’t be Will. Will wouldn’t register under an assumed name,” she said with quiet conviction. “And he isn’t in Madison City. He’s in Hollywood.”

“Do you know why he went to Hollywood?”

“I think he went there to sell a scenario.”

Selby took the photograph of the dead man from his inner pocket.

“I’m very sorry, Mrs. Larrabie,” he said, “but I’m afraid I’ll have to disillusion you. Please prepare yourself for a shock.”

He handed her the photograph. He noticed that her hand trembled as she took it. He saw her face grow gray.

This time her lips quivered.

“It’s Will,” she sobbed. “He’s dead.”

Mrs. Larrabie’s toil-worn fingers explored the pocket of the bathrobe. Sylvia, divining her intention, opened her purse and took from it a handkerchief, with which she dried the tears in Mrs. Larrabie’s eyes.

“Thank you, dear,” the woman said, “you’re very kind. Who are you?”

“I’m Sylvia Martin. I’m a newspaper reporter. Mr. Selby brought me with him. We’re trying to find out who … who … ”

Her voice trailed away into silence.

“Who what?” Mrs. Larrabie asked.

“The circumstances surrounding the death of your husband were very unusual,” Selby said. “We’re not entirely certain just what happened; but his death was directly due to an overdose of sleeping medicine; that is, what he thought was sleeping medicine.”

“Sleeping medicine?” Mrs. Larrabie said. “Why, Will didn’t take any sleeping medicine. He didn’t need to.”

“The circumstances,” Selby insisted, “are exceedingly unusual. In fact, we think that death was neither natural nor accidental.”

“You mean,” she asked, staring at him, her surprised incredulity for a moment overcoming the numbing effect of her grief, “Will was … murdered?”

“We’re making a complete investigation,” Selby said.

Mrs. Larrabie gave herself over to tears. She sobbed quietly into Sylvia Martin’s handkerchief. Selby sucked in a quick breath, about to say something, but Sylvia flashed him a warning glance and shook her head.

Outside, the first rays of sunlight gilded the spire of the church, filtered down through the leaves of a tree to make a shimmering pattern on the glass of the window.

Mrs. Larrabie continued to sob.

Finally, she said, “We were so close to each other. We’d been childhood sweethearts. Will had the most lovable, the most whimsical disposition … He had such a great faith in people … He was always going out of his way to aid people … Always looking for people in misfortune. He visited the jails, always wanted to help the unfortunate. That was going to cost him his position here. Mrs. Bannister thought he wasn’t devoting enough time to the members of the church. She was going to demand a change, and Will thought he could sell a scenario to the motion-picture people and make enough money to devote all of his time the unfortunate.”

Selby said very gently, “I’ve got to ask a lot of questions about your husband’s life. I must find out everything I can about the people with whom he came in contact, particularly about anyone who might have had any reason for wanting to harm him.”

She wiped her eyes, mechanically blew her nose on Sylvia’s handkerchief, then suddenly said apologetically, “Oh, you poor thing, I’ve ruined your handkerchief. Let me get you another and I’ll send this one back to you all freshly laundered.”

She got up from the chair and left the room.

Sylvia looked across at Selby, blinked her eyes and said, “Give me one of your h-h-h-handkerchiefs, D-D-Doug; I’m going to b-b-b-bawl myself.”

Selby came to her side, put his an around her shoulders, gave her his handkerchief.

“I’m a h-h-hell of a reporter,” she said, crying into the handkerchief. “I could have stood hysterics or wailing, but this quiet grief gets me. And right in the middle of it the poor thing had to think about my h-h-h-handkerchief. She’s always thought about others all her life.”

They heard her steps in the corridor and Sylvia said, “Here, quick, take back your handkerchief.”

Selby pocketed the handkerchief. Mrs Larrabie returned to the room, carrying with her a handkerchief from which came the faint odor of lavender.

“There, dear,” she said, smiling, “you take that, and I’ll be brave now. These things come to us. It’s all part of God’s plan.”

“You said you knew Charles Brower?” Selby asked.

“Yes. I met him Saturday.”

“You mean last Saturday?”

“Yes. My husband had known him it Denver. I don’t think he’s an ordained pastor. He preached on the streets. Many of the ministers wouldn’t cooperate with him, but Will said the man was doing as much good as any minister in town and became friendly with him, but he never brought him to the house. My husband had a church in Denver. That was about ten years ago.”

“And your husband had kept in touch with Mr. Brower ever since?”

“Yes, both of them were interested in helping unfortunate people, and I think they’d worked together on some case in Denver and the people they’d helped had become successful. Will was very mysterious about it. He said it was a sacred confidence.”

“And Mr. Brower was here Saturday?”

“Yes. That was the first time I’d met him.”

“You’re certain it was the same Charles Brower?”

“Why, my husband introduced him to me as the Reverend Charles Brower.”

“You have no children?”

“No, we had one baby, a girl, that died when it was two days old.”

“How did it happen that Mr. Brower came to visit your husband?”

“I don’t know. They’d been writing letters back and forth.”

“Where did Mr. Brower go when he left here?”

“Why, back to Millbank, I suppose.”

“How did he come? Did he drive, come on the train?”

“He drove. He has a little car, rather dilapidated, but it gets over the road.”

“And how did your husband go to Madison City?”

“I didn’t know he went to Madison City,” Mrs. Larrabie replied.

“You knew he went to Los Angeles?”

“Yes, to Hollywood.”

“How did he go?”

“On a bus, I think.”

“He has a car?”

She shook her head and said, “No, we haven’t needed one here. It’s rather a small town.”

“Did he have any hobbies?” Selby asked.

“Yes, helping people, hanging around the jails, and … ”

“No, I mean any hobbies aside from that. How about photography?”

For a moment her face underwent a change of expression. Then she said defiantly, “I think a man has to have some hobby in order to be normal. Will has been saving pennies for years. His camera gave him an outlet for his creative ability. He wrote a good deal, and that helped, but he wanted to do something. He didn’t have enough skill to paint, so he took up photography.”

“And a very good thing he did,” Selby agreed. “I certainly see no reason why he shouldn’t.”

“Well, Mrs. Bannister did,” Mrs. Larrabie said. “She said it was positively sinful for a man to squander his meager salary on things which weren’t necessary.”

“She was referring to your husband’s camera?”

“Yes.”

“When did he buy it?”

“In December. We saved all our pennies — for years.”

“Did he do his own developing work?”

She nodded. “He has a little dark room fixed up in the basement. Some of his pictures were beautiful. Of course, he didn’t take many. The films aren’t particularly expensive, but, even so, we have to watch every cent, and Will was always patient about such things. He sent one of his prints to a photographic magazine and it was published with honorable mention. They said it showed rare skill in composition.”

“What did Mrs. Bannister say to that?” Selby asked.

“She didn’t know anything about it … Oh, Mrs. Bannister is all right. I’m more bitter than I should be because she bothered Will so much. She simply couldn’t understand his temperament and she didn’t have enough patience to try, but she’s a very wonderful woman, a wonderfully religious woman. If it weren’t for her, the church couldn’t stay here. She contributes almost as much as all the other members put together.”

“How long have you been here in this church?”

“Five years.”

“Has it been rather difficult for Mr. Larrabie — under the circumstances?”

“He’s had his difficulties, yes, but everyone likes him. Of course, we’ve had to pinch and scrape on finances; but then, everyone does; and, at that, we’re a lot better off than some of the poor people who lost everything they had in the depression. Our wants are simple, and I think we get more out of life that way.”

“How does it happen,” Selby asked, “that your husband decided to go to Hollywood?”

“That’s something I can’t tell you about,” she said. “Will liked to be just a little mysterious about some of his business affairs.”

“And you don’t know why he went to Madison City?”

“No, I didn’t have any idea he was going to Madison City.”

“Could you show me where he worked?” Selby asked apologetically. “He had a study, I suppose? Was it in the church or … ”

“No,” she said, “it was right here. It opens off of this room.”

She opened a drawer in the table, took out a key and unlocked a door which opened from the parlor into a little den.

There was a roll-top desk, a bookcase and a homemade vertical file. Everything about the room was scrupulously neat. On the walls were two enlarged photographs.

“Will took those,” she said with pride, as Selby looked up at the photographs. “He enlarged them himself and made the frames.”

Selby nodded and said slowly, “I want to go through his file of correspondence, Mrs. Larrabie. I’m very anxious to find carbon copies of some of the letters which your husband wrote before he made this trip.”

“He never kept carbon copies of his letters.”

“He didn’t?”

“No. He did a lot of typing, but I don’t think he made carbon copies of anything. You see, it adds to the expense, and, really, there’s no reason for it. Most of the stuff in that filing case is sermons he’s written and notes on sermons, also stories. He wrote stories and scenarios. Not very many of them, but a few.”

“Did he ever sell any?”

“No, they all came back.”

Selby said slowly, “We’re going back to Madison City, Mrs. Larrabie. I presume, under the circumstances, you’ll want to go back to — to take charge of things. I think perhaps it’ll be necessary for you to answer some questions before the grand jury, and I’m going to give you a subpoena. It’s just a formality, but it will enable you to get your traveling expenses.”

When she made no answer, Selby turned from his survey of the room to look at her. Her tear-filled eyes were fastened upon the vacant chair in front of the rolltop desk. Apparently its full significance was just dawning on her.

The district attorney caught Sylvia’s eyes and nodded. Without a backward glance they tiptoed from the room.

XI

They returned to Madison City by train. As the rumbling Pullman clicked smoothly over the rails, nearing the familiar environs of the city, Sylvia Martin went forward to the vestibule, where Selby, standing braced against the motion of the car, was moodily regarding the scenery while he smoked a cigarette.

“Listen,” Sylvia said, “I know the wife of a Methodist minister here quite well. Don’t you think it would be a good plan, under the circumstances, to have her go there?”

Selby nodded.

“Why so pensive?” she asked him.

“I’m just thinking,” Selby said, “that I may have overlooked a bet.”

“How?”

“About that Brower angle. I should have made arrangements to locate him and have him subpoenaed as a witness. He knows more about this thing than we do.”

“You think that he knew Larrabie was going to Madison City?”

“Of course he did. What’s more, he must have known that Larrabie was going to register under his name.”

“Why? What makes you think that?”

“Because Brower gave Larrabie his cards and his driving license.”

“Unless Larrabie … No, he wouldn’t have done that.”

The district attorney smiled and said, “No, I would hardly gather that Larrabie was one who would knock his friend on the head with a club in order to get possession of an automobile which was probably worth less than fifty dollars.”

“I wonder if they didn’t come here together.”

Selby shrugged his shoulders and said, “This is too deep for me, and I have a hunch it’s going to be a humdinger — one of those everyday sort of cases where everything seems to be so confoundedly simple that all you have to do is to pick up the pieces and put them together. But when you pick up the pieces you find they just don’t go together.”

The train whistled for Madison City, started to slow to a stop.

Selby finished his cigarette. The train ground slowly to a stop. The porter opened the vestibule door. Selby stepped to the platform, helped the two women to alight.

He took a cab to his apartment, realized that he’d need to go to Los Angeles to retrieve the automobile he’d left at the airport. He felt a swift thrill of anticipation and realized that it was due to the fact he’d remembered his promise to Shirley Arden.

He turned hot water into his bathtub, telephoned the courthouse and asked for the sheriff. When he heard Rex Brandon’s voice on the line he said, “Okay, Rex, we’re back.”

“You brought the woman with you?”

“Sylvia Martin has her in tow. Just between you and me, Sheriff, I think she’s worked out some deal with her for exclusive story privileges.”

“Okay by me,” Brandon said. “The Clarion stuck up for us during the election. You didn’t see last night’s Blade, did you, Doug?”

“No.”

“Better take a look at it. They’ve got a pretty good roast in there. What’s this about the motion-picture actress you’re shielding having told you the man’s name?”

Selby gripped the receiver so tightly that his knuckles ached.

“What’s that? Something in The Blade about that?”

“Yes. They’ve put it up in rather a dirty way. They’ve intimated that you’ve been reached by money or influence, or both; that you’re throwing up a big smoke screen to protect some prominent motion-picture actress who’s involved in the murder; that you met her at a secret conference and she told you who the murdered man really was. The Blade threatens to publish her name.”

“Good heavens!” Selby said.

“Anything to it?” the sheriff asked.

“Yes, and no,” Selby told him. “I’m protecting Miss Arden … that is, I simply didn’t make her name public because I’m satisfied she had no connection with the case. I’d have told you about it if it hadn’t been necessary for me to rush up to Riverbend to make that identification absolute.”

“I was wondering,” the sheriff said slowly, “how it happened you were so certain that Larrabie of Riverbend was the man we wanted.”

“Let’s not talk about this thing over the telephone,” Selby said.

“I’m just going to the Madison Hotel,” the sheriff said. “I understand Cushing’s found a guest who heard some typing across in 321. Suppose you make it snappy and meet me there.”

“I’m all grimy from travel,” Selby said. “I’m just climbing into the bathtub, but I can make it in about fifteen or twenty minutes.”

He dropped the receiver back into place.

So The Blade knew about Shirley Arden, did they? And they’d turned the blast of dirty publicity on her. Damn them!

Selby tubbed hastily and met Sheriff Brandon in exactly twelve minutes from the time of the telephone call.

“Listen,” he said, “I’m getting fed up on this yellow journalism. I’m … ”

“Take it easy, son,” Rex Brandon advised, starting the car toward the Madison Hotel. “You’ve fought your way through a lot of stuff without losing your head. Don’t begin now.”

“I can take it, as far as I’m concerned,” Doug Selby went on, “but when it comes to dragging in a woman, jeopardizing the career of an actress and perpetrating the dastardly libel by insinuation I get all fed up.”

“The best way to win a fight,” the sheriff remarked, “is never to get mad; if you must get mad, never let the other fellow know it. Now, get a smile on your face. We’re going up and find out about that typewriting business. Maybe we’ll run onto Bittner and maybe we won’t. But, in any event, you’re going to walk into that hotel smiling.”

He swung his car in to the curb in front of the hotel. Together the two men entered the lobby.

George Cushing came toward them, his face twisted into a succession of grimaces. His head jerked with St. Vitus-dancelike regularity toward the counter, where a man in a blue serge business suit was engaged in a low-voiced conversation with the clerk. On the counter in front of the man was a letter.

“Step right this way, gentlemen, if you’re in search of rooms,” Cushing said, and, taking the surprised sheriff by the arm, led him over to the counter.

The clerk looked up at Brandon and the district attorney. Recognition flooded his features, then gave place to a look of puzzled bewilderment.

“They’re strangers in the city,” Cushing repeated. “They want rooms. Go ahead and dispose of your business with this man.”

The man in the blue suit was too engrossed in his own affairs to give any particular heed to the conversation.

“It’s my money,” he said, “and I’m entitled to it.”

Cushing bustled importantly behind the counter and said, “What seems to be the trouble, Johnson?”

“This man says that he’s entitled to an envelope containing five thousand dollars which Mr. Brower left on deposit in the safe.”

Brandon moved up on one side of the man at the counter. Selby moved to the other side and nodded to Cushing.

“I’m the manager here,” Cushing said. “What’s your name?”

“You heard what I had to say a few minutes ago. You were standing over there by the safe. You heard the whole thing,” the man said.

“I wasn’t paying any particular attention to it,” Cushing said. “I thought it was just some ordinary dispute. Mr. Brower is dead, you know. We can’t hand over the money without some definite assurance that it’s yours.”

“I don’t know what more you want than this letter,” the man said. “You can see for yourself it says the money is mine.”

Cushing picked up the typewritten letter, read it, then placed it back on the counter, turning it so that Selby and the sheriff could read it without difficulty.

The letter was addressed to George Claymore, at the Brentley Hotel in Los Angeles. It read:

My dear George: You’ll be glad to learn that I’ve been successful in my mission. I have your five thousand dollars in the form of five one-thousand-dollar bills. Naturally I’d like to have you come up as soon as possible to get the money. I don’t like to have that amount in my possession and, for obvious reasons, I can’t bank it. I’ve given it to the clerk to put in the safe here at the hotel.

I am signing this letter exactly the way I have signed my name on the envelope, so the clerk can compare the two signatures, if necessary.

With kindest fraternal regards, and assuring you that this little incident has served to increase my faith and that I hope it will strengthen yours, I am,

Sincerely,

CHARLES BROWER, D.D.

Down below the signature in the lower left-hand corner was typed “Room 321, Madison Hotel.”

“Perhaps I can be of some assistance to you,” Selby volunteered. “I happen to know something about Mr. Brower’s death. You’re Claymore, are you?”

“Yes.”

“And that, of course, is your money?”

“You can read plainly enough what this letter says.”

“You were in Los Angeles at the Bentley Hotel when you received this letter?”

“Yes.”

“Let’s see when it was mailed. It’s postmarked from here on Tuesday. When did you get it?”

“I didn’t get it until late last night.”

“That’s poor service,” Selby said.

The other man nodded. There seemed about him a curious lack of self-assertion.

“Well,” Claymore said, “it was like this. You see … ”

He broke off, stared at the elevator, then turned abruptly toward the door.

“I’ll be right back,” he said.

Sheriff Brandon grabbed the man’s coattails, spun him around, flipped back his own coat lapel to show a gold-plated star.

“Buddy,” he said, “you’re back right now. What’s the game?”

“Let me alone! Let me go! You’ve got no right to hold me! You … ” He became abruptly silent, turned back toward the counter, stood with his shoulders hunched over, his head lowered.

Selby looked toward the elevator. Mrs. Charles Brower was marching sedately toward the street exit.

“She staying here?” he asked Cushing.

“Yes, temporarily. She’s insisting that someone pay her expenses. She’s hired Sam Roper.”

Selby said to Brandon, “Turn him around so he faces the lobby, Rex.”

The sheriff spun the man around. He continued to keep his head lowered.

Selby raised his voice and called, “Why, good morning, Mrs. Brower.”

The woman turned on her heel, stared at Selby, then, as recognition flooded her countenance, she bore down upon him with an ominous purpose.

“I’ve never been to law,” she said, “but I’ve got some rights in this matter, Mr. Selby. I just wanted you to know that I’ve consulted a lawyer and … ”

She broke off, to stare with wide, incredulous eyes.

“Charles!” she screamed. “What are you doing here?”

For a moment Selby thought that the man wasn’t going to raise his head. Then he looked up at her with a sickly smile, and said, “As far as that’s concerned, what are you doing here?”

“I came here to identify your body.”

He wet his lips with his tongue, said in a burst of wild desperation, “Well, you see, I — I read in the paper I was dead, so I came here to see about it.”

“What about this five thousand dollars?” Brandon asked.

The man whirled. The typewritten letter was still on the counter. His face held the expression of a drowning man, looking frantically about him, trying to find some straw at which he might clutch.

“What letter?” Mrs. Brower asked, moving curiously toward the counter.

Selby folded the letter and envelope and thrust it in his pocket. “This your husband?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Let’s let him tell about it.”

Brower clamped his lips together in a firm, straight line.

“Speak up, Charles! What’s the matter with you?” Mrs. Brower snapped. “You haven’t been doing something you’re ashamed of, have you?”

Brower continued to remain silent.

“Go on, speak up,” Mrs. Brower ordered.

There was something in the dominant eye of his wife which brought Brower out of his silence, to mumble, “I don’t think I’d better say anything right now, dear. It might make trouble for everyone, if I did.”

“Why, what’s the matter with you? You jellyfish!” she said. “Certainly you’re going to speak up. Go right ahead and tell your story. You’ve got to tell it sooner or later, and you might just as well tell it now.”

Brower shook his head. Mrs. Brower looked at the men helplessly.

“Well, of all things!” she said.

“I’m afraid,” Selby said, “that if you don’t speak up, we’re going to have to detain you for questioning, Mr. Brower.”

A little crowd had collected in the lobby, and the interested spectators served as a magnet to draw more curiosity seekers.

The sheriff said quietly, “I think I’d better take him along with me, Doug. You stay here and look into that other angle. Then come on up to the jail. Perhaps he’ll have changed his mind.”

Selby nodded.

“Make way, folks,” Brandon said cheerfully.

Mrs. Brower swung into step beside her husband and the sheriff. “Don’t think you’re going to take him where I can’t talk to him,” she said grimly. “He’s got an explanation to make to me … Out on a motor trip, huh? Resting his nerves, eh! The very idea!”

Selby caught Cushing’s eye, jerked his head toward Cushing’s office and said, “Let’s have a little chat.”

Selby followed the hotel man into the office and faced him.

“What about it?” the district attorney asked.

“This chap showed up out of a clear sky,” Cushing said; “came walking up to the desk big as life, and asked if Mr. Brower was in his room. The clerk was flabbergasted. I was over by the safe. I pretended not to be taking any great interest in the conversation. The clerk told him, no, Mr. Brower wasn’t in, and then the chap produced that letter and said Brower had left five thousand dollars in the safe for him. I signaled the clerk to stall him along, and I was just starting for the telephone booth to put in a call for you when you came walking in the door.”

Selby said, “Get out that envelope. Let’s check the signatures.”

“I haven’t it,” Cushing answered. “The sheriff took it up and locked it in his safe yesterday night.”

“All right, I’ll keep the letter,” Selby said. “Now, I understand there was someone who heard typewriting in 321.”

“Yes, a Miss Helen Marks.”

“What’s her story?”

“She heard typing in 321 when she came in Monday night. She says it was sometime around midnight.”

“I think I’ll talk with her,” Selby said. “Give her a ring and tell her I’m coming up.”

“Listen,” Cushing pleaded, “this thing keeps getting worse and worse. Guests are commencing to get frightened. Now, I’m entitled to some consideration from your office, Selby. I want you to catch that murderer.”

Selby grinned and said, “Perhaps if you hadn’t been so insistent that we hush it all up at the start, we might have got further.”

“Well, that looked like the best thing to do then. You can understand my position. I’m running a hotel, and … ”

Selby clapped him on the back and said, “Okay, George, we’ll do the best we can. What was that number — 372?”

“Right.”

Selby took the elevator to the third floor and knocked on the door of 372. It was opened almost immediately by a dark-complexioned young woman in the early twenties. Her eyes were very large and smoke-gray. She wore a checked black-and-white tailored suit. Make-up showed bright patches of color on her cheeks. Her lips were smeared with lipstick until they were a glossy red.

“You’re Mr. Selby,” she asked, “the district attorney?”

“Yes.”

“I’m Helen Marks. Come in. They said you were coming up to see me.”

“You heard the typewriting in Room 321?” Selby asked.

“Yes. It was Monday night.”

“What do you do for a living? Do you work?”

“I’m not doing anything at present. I have been a secretary and a night club entertainer. I’ve clerked in a dry-goods store and have done modeling work in Los Angeles.”

“What time was it you heard the sounds of the typewriting?”

“I don’t know. It was when I came in. Sometime around midnight, I would say, but that’s just a guess.”

“What had you been doing?”

“I’d been out with a boyfriend.”

“Doing what?”

Resentment showed in her eyes. “Is that necessary?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“We went to a picture show.”

“Not until midnight.”

“No, then we had some drinks and danced.”

“Then what?”

“Then he drove me to the hotel.”

“Straight to the hotel?”

“Yes, of course.”

“Did he see you as far as the elevator?”

“Well, yes,” she said, “he came to the elevator with me.”

“Could this have been before midnight?”

“No, I’m sure it wasn’t before midnight.”

“Probably after midnight, then?”

“Perhaps.”

“How much after?”

“I don’t know. I didn’t look at my watch. I’m not accountable to anyone, and I don’t have to tell anyone just what time I came in.”

“You heard this typewriting distinctly?”

“Yes.”

“Why didn’t you say something sooner?”

“I didn’t think it was important.”

“You’ve made a living by running a typewriter?”

“Yes.”

“How did this typing sound to you? Was it the ragged touch of the hunt-and-peck system, or was it done by the touch system?”

“It was fast typing,” she said. “I don’t believe I could tell whether it was a touch system, but that typewriter was going like a machine gun.”

“How long did you hear it?”

“Just while I was walking past the door.”

Selby said casually, “And your boyfriend, I presume, can verify your statement?”

“Yes, certainly … Why, what do you mean?”

Selby smiled at her.

“Well,” she said, defiantly, “he came as far as my room.”

“Did he stay?”

“He did not.”

“Just went to the door of the room?”

“Well, he kissed me good night.”

“Once or more than once?”

“Listen,” she said, “get this straight: This is the reason I didn’t want to say anything about what I’d seen. I was afraid a lot of people would start asking questions that were none of their business. I’m straight. If I wasn’t, it’s no one’s business except my own. The boy I was out with is a nice chap. I’ll say that for him. He’s a perfect gentleman and he knows how to treat a woman. He came as far as the room. He was here perhaps five minutes. He kissed me good night and, believe it or not, he was darn nice and sweet about it.”

“Can’t you place that time a little more closely?” Selby asked.

“It was right around three o’clock in the morning,” she said sullenly.

“That’s better. Have you any way of fixing the time — definitely?”

“We danced until about a quarter to three. My boyfriend said he had to work in the morning and he couldn’t make too big a night of it. So we came directly to the hotel.”

“And you don’t think he was here more than five minutes?”

“No.”

“You didn’t go as far as the elevator with him when he left?”

“Of course not. He saw me to my room and that was all. When he left, I locked the door, took my clothes off and tumbled into bed. I was a little weary myself.”

Selby nodded.

“What’s the name of your boyfriend?” he asked.

“It’s Herbert Perry,” she said. “He’s working at a service station in … ”

Selby stiffened to electrified attention.

“Herbert F. Perry?” he asked. “The young man who’s bringing a suit to determine heirship to the Perry Estate?”

She frowned for a moment and said, “I guess that’s right. He said something about some lawsuit he was in. I gathered from the way he talked he didn’t think he stood much chance of winning it. But he said if he could win it there’d be a big bunch of money in it for him.”

“And you don’t know where he went after he left this room?”

“Why, he went down in the elevator, of course.”

“But you didn’t see him go.”

“No, of course not.”

“How long have you known Herbert Perry?”

“To tell you the truth,” she said, “I just met him that night.”

“Who introduced you?”

She stared defiantly at the district attorney and said, “It was a pick-up, if you want to know.”

“On the street?”

“Certainly not! I stopped in at the bar at the Blue Lion for a drink. This boy was there. He was very nice. We got to talking.”

“Did he,” Selby asked, “seem to know anything about you?”

“What do you mean by that?”

“Did he know where you lived?”

“Come to think of it,” she said, “he did say that he’d seen me a couple of times at the hotel and had inquired something about me. He knew my name. He said he’d been wanting to meet me for a week, but didn’t know just how to arrange it. He was an awfully nice chap.”

Selby smiled, and said as casually as possible, “Well, thanks very much for coming forward with the information. Don’t change your address without letting me know, because it may be important. It’s rather difficult to believe that this man was alive and writing on his typewriter at that hour in the morning. You don’t think there’s any possibility you could be mistaken in the room?”

“No, because I noticed there was a light coming through the transom. I wondered who could be writing at that hour in the morning.”

Selby smiled, thanked her again and sauntered casually out to the corridor. As soon as he heard the door close behind him, however, he raced for the elevator. In the lobby he crossed to the telephone booth, grabbed up the receiver and said to the operator in an excited voice, “Get me the sheriff’s office, quick!”

XII

Herbert Perry sat in the district attorney’s office, facing the light. The sheriff and Douglas Selby concentrated upon him steady stares of silent accusation.

“Now, listen,” he said, “this Marks girl is a nice kid, see? She’s on the up-and-up. Of course, it was a pickup, but that’s the way things go nowadays.”

Selby said coldly, “I still can’t see why you knocked on the door of 321.”

“Well, that’s what I’m trying to lead up to. She’s a good kid. She wanted to sleep. I’d had a couple of drinks and I was feeling chivalrous. This typewriter was making a racket like a machine gun. The transom was open. You could hear the thing clacking all up and down the corridor. I figured it’d be a swell thing to tell this guy it was bedtime, see?”

Perry twisted his neck around inside his collar, took a deep breath and went on: “It was the thing anyone would do under the circumstances. The kid was trying to sleep. Lots of people in the hotel were trying to sleep. I’d had four or five drinks. I was feeling pretty good — not jingled, you understand, but mellow and protective — so I took the girl home and dated her up for a night next week. Then, when I started toward the elevator, I felt kind of boy-scoutish, so I tapped on the door.”

“What happened?”

“The typewriter stopped.”

“Did you knock again?”

“No.”

“Did you say anything?”

“No, not after he stopped typewriting. I figured there was no use doing anything else … ”

Perry seemed pathetically eager to have them believe his explanation.

Selby tapped the top of his desk with an impressive forefinger and said, “Now, listen, Perry, you and I might just as well understand each other now as later. You knew this man in 321.”

“I knew him?” Perry exclaimed, his eyes wide.

“Yes, you knew him. He came here to see you in connection with that lawsuit.”

“You’re crazy!” Perry said; then, catching himself, said quickly, “I beg your pardon, Mr. Selby, I didn’t mean that. You know, I was just speaking hastily. I didn’t mean to be disrespectful, but the idea’s all cuckoo. I never heard of the man in my life.”

Sheriff Brandon said slowly, “Look here, Perry, we know that this man was interested in your lawsuit. He’d made a collection of newspaper clippings about it.”

“Lots of people are interested in it,” Perry said sullenly.

“But this man had some particular reason to be interested in it.”

“Well, suppose he did?”

“We want to know what that interest was,” Selby said.

“You’ll have to ask someone else. I can’t tell you.”

Once more the officers exchanged glances.

“The typewriting stopped the first time you knocked on the door?”

“Yes.”

“You don’t know how long the typewriting had been going on?”

“No, the man was typing when I got out of the elevator.”

“And you say it sounded like a machine gun?”

“I’ll say it did.”

“Were there any pauses?”

“Not a pause. The thing was being ripped off at high speed, by someone who knew what he was doing.”

“And you didn’t go into Helen Marks’ room?”

“No, I just saw her to the door.”

“How long did you stay there?”

“Just long enough to kiss her goodnight.”

“And you don’t know any reason why this man was interested in your lawsuit?”

“No,” Perry said; then, after a moment’s hesitation, added, “I wouldn’t want this repeated, but I’m afraid it isn’t much of a lawsuit, Mr. Selby. I’m willing to settle for anything I can get, but I don’t think I can even get an offer. I need money — need it bad.”

“As I see it,” Selby remarked, keeping his eyes fixed on the younger man, “the whole thing hinges on the question of whether a marriage ceremony had been performed. Now, here’s a man who’s a minister of the Gospel who’s taken an interest in the case. Naturally, the first thought which comes to my mind is that he must have known something about a marriage ceremony.”

Perry shook his head and said, “My lawyers have searched the records everywhere. It doesn’t make any difference if a marriage ceremony was performed, if it wasn’t a legal marriage ceremony; and the law says a marriage ceremony isn’t legal unless there’s been a license issued and a ceremony performed in the county where the license was issued; and then there has to be some registration made, some certificate that the marriage was performed. We’ve searched the records everywhere and find that the folks never even took out a license. They thought their marriage in Yuma was good.”

“They might have gone out of the state somewhere and married and this man might have known about it.”

Perry shook his head and said, “No, that’s out too. The folks made one trip up to Oregon. Aside from that, they stayed right there on the home place. You know, they were pretty much stay-at-home sort of people.”

“When did they go to Oregon?”

“About a year ago.”

“And you’re certain they didn’t get married in Oregon?”

“Yes, we’ve traced them everywhere. Of course, Mr. Selby, I’m telling you this in strict confidence. My lawyer’s putting up the best bluff he can and trying to get a settlement. He’ll get half if he does, so he’s working hard.”

Brandon said, not unkindly, “That’s all, Herbert. Go on back to the service station, and don’t tell anyone you’ve been questioned.”

When Perry had closed the door behind him, the sheriff and Doug Selby hitched their chairs closer together. “The kid’s telling the truth,” Brandon announced.

“I know it,” Selby said, “but it’s such a peculiar coincidence that he should have been the one to knock on the door.”

“Coincidences happen like that in real life all the time.”

Selby said slowly, “I’m wondering if there’s a reason that this Marks girl picked up this particular young man and brought him to the hotel at a certain particular time.”

Brandon shrugged his shoulders.

“And you can’t get anything out of Brower?” Selby asked.

“Not a thing,” Brandon said. “He’s close-mouthed as a clam. And his wife smells a rat somewhere. She wants him to talk — but to her, and not to us. She rushed out and got him a lawyer … Where do you suppose Larrabie got that five thousand dollars from?”

“That’s a problem,” Selby remarked. “Hang it, I never saw a case which looked so beautifully simple on the face of it. But everything we touch goes haywire. His wife says he never had five hundred dollars. If he had as much as fifty dollars ahead, he thought he was rich.”

“I think the actress paid it,” Brandon insisted.

Selby laughed. “Don’t be silly. In the first place, why would she have paid it? In the second place, if she had, she isn’t the kind to have lied to me about it.”

“We can’t be too sure,” the sheriff said slowly. “People do funny things. There may have been blackmail mixed up in it.”

“Not with Larrabie,” Selby said. “He’s too absolutely genuine. He was busy making the world a better place to live in.”

“Maybe he was,” Brandon agreed, “but I’m not so sure about Brower. And remember Brower had raised five thousand bucks toward a church.”

“Yes,” Selby admitted, “and he had five thousand in life insurance, and Larrabie wrote Brower, who was registered under the name of Claymore, saying that he’d been successful in his mission and had the five thousand dollars, as though it had been money he’d raised for Brower. Try and figure that out.”

“Somehow, I think Brower’s our man,” Brandon said slowly. “He may have something on his mind besides the murder, but I think Brower either did it or knows who did it.”

“It’s funny he’d keep silent.”

“He won’t say a word, and his wife rushed right out and hired Roper to defend him.”

“What did Roper do?”

“Demanded to see his client. Told him to keep still and not say anything, to answer no questions whatever. And then he demanded we put a charge against him or turn him loose. He claims he’s going to get a writ of habeas corpus.”

“Let him get it,” Selby said, “and in the meantime we’ll trace every move Brower made from the time he left Millbank until he showed up here.”

The sheriff nodded. “The Los Angeles sheriff’s office is going to co-operate. By tomorrow I’ll know everything about Brower, whether he wants to talk or not. Well,” he went on as he rolled a cigarette, “I wonder what The Blade will have to say about it tonight.”

“Probably plenty,” Selby admitted, then went on to say, “You can gamble on this: Brower and Larrabie hatched up some sort of scheme. Larrabie came here as a part of that scheme.”

“Well, if Larrabie got the money, and that was all there was to it, why didn’t he go down to Los Angeles and join Brower or telephone for Brower to meet him back in Millbank?”

Selby nodded slowly.

“If you were a stranger in town, Doug, and wanted to get five thousand, how would you go about it?” the sheriff asked.

“I’d hold up a bank or something.”

“Or perhaps indulge in a little blackmail.”

“You’d have a sweet time getting five thousand bucks in blackmail out of anyone in this town,” the district attorney said. “And, even then, there wouldn’t be any excuse for sticking around afterward.”

“And in five one-thousand-dollar bills,” the sheriff remarked significantly, starting for the door. He turned as he opened the door, to say, “I keep thinking about that actress angle. Those bills look like outside money to me.”

“Forget it,” Selby insisted. “I had a good heart-to-heart talk with her.”

“Yeah, you might have had a better perspective on the case if you’d talked over the telephone.”

He slammed the door as Selby jumped to his feet.

Selby was still scowling savagely when Amorette Standish tiptoed into the room and said, “Sylvia Martin’s out there.”

“Show her in,” Selby said.

Sylvia bustled into the office with a folded newspaper under her arm.

“How’s it coming?” she asked. “And what’s this about Brower?”

“Brower tried to claim the money at the hotel,” Selby said.

“What money?”

“Five thousand dollars that was left in an envelope by Larrabie.”

“You didn’t tell me about this.”

“I was keeping it a secret. I didn’t know about it myself until sometime after viewing the body. Cushing had the envelope in his safe. Of course, he didn’t know what was in it, so he didn’t consider it as being very important.”

“Where did Larrabie get the five thousand dollars?”

“That,” he told her, “is what we’re trying to find out.”

“And why did he take Brower’s name?”

Selby shrugged his shoulders and said shortly, “You guess for a while, I’m tired.”

Sylvia sat down on the edge of his desk and said, “Listen, Doug, how about that actress?”

“Oh, well,” Doug said, “I may as well tell you the whole truth. I guess you are right, after all. The Blade will publish the story, if you don’t, and it’s better for you to publish it the way it is than to let people read about it the way it wasn’t.”

He began at the beginning and told her the entire story of his meeting with Shirley Arden.

When he had finished, she said, “And there was the odor of perfume on that money?”

“Yes.”

“What sort of perfume?”

“I can’t tell you,” he said, “but I’d know it if I smelled it again. It was rather a peculiar perfume, a delicate blend.”

“Did you,” Sylvia asked, watching him with narrowed eyes, “take the precaution to find out what sort of perfume she was using?”

Selby nodded wearily and said, “I regret to say that I did.”

“Why the regrets, Doug?”

“Oh, I don’t know. It was cheap. It was doubting her word, somehow.”

“And the perfumes weren’t the same?”

Her voice was like a cross-examiner getting ready to spring a trap.

Selby’s reply contained a note of triumph. “I can assure you,” he said, “that they were most certainly not the same.”

Sylvia whipped from under her arm the newspaper she was carrying. She jerked it open, spread it out on the desk and said, “I don’t suppose you bother to read the motion-picture gossip in the Los Angeles daily periodicals.”

“Good Lord, no,” Selby exclaimed.

Sylvia ran her finger down a syndicated column dealing with the daily doings of the motion picture stars.

“Here it is,” she said. “Read it.”

Selby bent forward and read:

It’s a well-known fact that people get tired of living in one house, of being surrounded by one environment. Stars feel this just the same as others. Perhaps the best illustration of that is the case of Shirley Arden’s perfume.

Miss Arden’s personality has never been associated with that impulsive temperament which has characterized most stars who have won the hearts of the picturegoers through the portrayal of romantic parts. Yet, upon occasion, Miss Arden can be as impulsively original in her reactions as even the most temperamental actress on the lot.

Witness that for years Miss Arden has been exceedingly partial to a particular brand of perfume, yet, overnight, she suddenly turned against that scent and gave away hundreds of dollars of it to her stand-in, Lucy Molten.

Moreover, Miss Arden would have nothing to do with garments which even bore the smell of that perfume. She sent some to be cleaned, gave others away. She ordered her perfumer to furnish her with an entirely new scent, which was immediately installed on her dressing table both at home and in the studio.

I trust that Miss Arden will forgive me for this intimate revelation, which, for some reason, she apparently tried to clothe in secrecy. But it’s merely one of those examples of outstanding individuality which mark the true artist.

Selby looked up into Sylvia Martin’s eyes, then reached for the telephone.

“I want to get Shirley Arden, the picture actress, in Hollywood,” he said to the operator. “If I can’t get her, I’ll talk with Ben Trask, her manager. Rush the call.”

He slammed the telephone speaker back into its pronged rest. His lips were clamped tightly shut.

Sylvia Martin looked at him for a moment, then crossed to his side and rested her hand on his shoulder.

“I’m sorry, Doug,” she said, and proved the extent of her understanding and sympathy by saying nothing more.

TO BE CONTINUED (READ PART IV)

Featured image: Illustrated by Dudley Gloyne Summers; SEPS.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now