Writing young adult fiction in Boy’s Life, Child Life, and Boy Scout Magazine, B.J. Chute’s work ranges from fantastical romance to silly farce. In 1944’s “Come of Age,” her short story about a young boy coping with the unimaginable, Chute depicts the innocence of World War II-era America alongside devastating grief in the eyes of a child. As a product of its time, the story gives a snapshot of idyllic family life interrupted by the horror of war.

Published on September 30, 1944

Content Warning: A racial slur

Timothy crossed the road at the exact place where the tar ended and the dirt began, paused on the sidewalk, squinted up at the sun and gave a heave of satisfaction. He was too warm with his sweater on. He had known he was going to be too warm, and he had made a firm announcement to this effect to his mother before he left the house in the morning. Thousands of layers of woolly stuff, he had pointed out darkly, intimating that a person might easily suffocate.

Having barely survived this fate so far, he now decided to make a test case out of it. If an automobile passed him on the road before he had counted up to ten, that meant it was really spring and too warm for sweaters. His own internal workings were positive on the subject, but he was amiably willing to put the whole thing on a sporting basis.

“One,” said Timothy. After a while he added, “Two.” He then suspended his counting while he made a neat pile of his schoolbooks and lunch box, putting them carefully on a bare patch of ground, away from the few greenly white sprigs of grass that were struggling up into the sunlight. If the car came by, he would have to put the books on the ground anyhow, in order to take off his sweater, so it seemed wiser to do it ahead of time.

“Three,” said Timothy, looking up the road. There was nothing in sight, so he closed his eyes, waited, said “Four” and opened them again. This time it worked. There was a car coming. Timothy put his hands to his sweater and stood pantingly prepared to jerk it over his head.

The car swished by with a friendly toot.

“Five-six-seven-eight-nine-ten,” said Timothy rapidly, just to be perfectly fair about the whole thing, vanished momentarily into the sweater and reappeared with his hair standing on end and the expression of one who had been saved from total collapse in the nick of time.

He turned the sweater virtuously right side to again, with his mother in mind, and tied its arms around his waist, allowing the rest of it to fall comfortably to the rear, where it could flap without giving him any sense of responsibility. Then he tucked his schoolbooks under one arm, picked up the lunchbox and peered hopefully inside it. There were three cake crumbs and some orange peel. He licked his finger, collected the crumbs on the end of it and disposed of them tidily, then extracted a piece of the peel and took a thoughtful nibble.

It tasted vaguely like a Christmas tree, but rather leathery, so he put it back, felt a momentary dejection based on a sudden desperate need for a great deal of food, recovered rapidly, took another look at the sun and gave a pleased snort.

It was certainly spring, and for once it was starting on a Friday afternoon, which meant he would have the whole weekend to get used to it in. Also, by some great and good accident, his sixth-grade English teacher had forgotten to assign the weekly composition. This was almost incredibly gratifying, especially since the rumor had got around that she had been going to give them the dismal topic of What My Country Means to Me.

Timothy sighed with satisfaction over the narrow escape of the sixth-grade English class, knowing quite well the same topic would turn up again next week, but that next week was years away. Besides, she might change her mind and assign something else. One week she had told them to write what she referred to as a word portrait, called A Member of My Family. Timothy had enjoyed that richly. He had written, inevitably, about his brother Bricky, and it was the longest composition he had ever achieved in his life. He felt a great pity for his classmates, who didn’t have Bricky to write about, since Bricky was not only the most remarkable person in the world but he was at that moment engaged in being a hero in the South Pacific. He was a pilot with silver wings and a bomber, and Timothy basked luxuriously in the warmth of his glory.

“Yoicks,” said Timothy, addressing the spring and life in general. “Yoicks” was Bricky’s favorite expression.

“Yoicks,” he said again.

He was, at the moment, five blocks from home. The first block he used up in not stepping on the cracks in the sidewalk, which was not the mindless process it appeared to be. He was actually conducting an elaborate reconnaissance program, and the cracks were vital supply lines. By the second block, however, his attitude on supplies had taken a more personal turn, and he spent the distance reflecting that this was the day his mother baked cookies. His imagination carried him willingly up the back steps, through the unlatched screen door and to the cooky jar, but there it gave up for lack of specific information on the type of cookies involved.

Besides, he was now at the third block, and the third block was important, consisting largely of a vacant lot with a run-down little shack lurching sideways in a corner of it. The old brown grass of last autumn and the matted tangle of vines and weeds were showing a faint stirring of greenness like a pale web.

At the edge of the lot, Timothy paused and his whole manner changed. He became alert and his eyes narrowed, shifting from left to right. He was listening intently. The only sound was the peevish chirp of a sparrow; but Timothy was a world away from it. What he was listening for was the warning roar of revved-up motors.

In a moment now, from behind that shack, from beyond those tangled vines, Japanese planes would swarm upward viciously, in squadron attack.

Timothy put down the books and the lunch box, then he stepped back, holding himself steady. His hand moved, fingers curved knowingly, to control and throttle, and from his parted lips there suddenly burst a chattering roar.

The Liberator surged forward gallantly to meet the attackers. Timothy’s face became tense, and he interrupted the engine’s explosive revolutions for a moment to warn himself grimly, “This is it. Watch yourselves, men.” He then nodded soberly. It was a grave responsibility for the pilot, knowing the crew trusted him to see them through.

The pilot, of course, was Bricky. It was Bricky who was holding the plane steady on its course, nerving himself for the final instant of action. The deadly swarm of Zeros swept forward, but the pilot’s face remained impassive.

Z-z-z-zoom, they spread across the sky, their evil advance punctuated by the hail of machine-gun fire. The Liberator climbed, settling back on her tail in instant response to the pilot’s sure hand. As she scaled the clouds, the bright silver of her name, painted along the side, shone defiantly — The Hornet. Bricky had at one time piloted a plane called The Hornet. It was the best name that Timothy knew.

After that, it was short and sharp. A Jap fighter detached itself from the humming swarm. The Hornet rolled and the tail gunner squeezed the triggers. The plane exploded in midair, disintegrated and streamered to earth in flaming wreckage.

“Right on the nose,” said the gunner with satisfaction.

The Hornet had their range now. Zero after Zero fluttered helplessly down out of the sky, dissolving into the earth. The others turned and skittered for their home base, terrified before the invincibility of American man and machine.

A faint smile flickered across the face of The Hornet’s pilot, and he permitted himself a nod of satisfaction. “Good show,” he said.

Timothy sat down on the ground and drew a deep breath. Then he said “Gosh!” and scrambled back to his feet. At home, even now, there might be a letter waiting from Bricky, full of breathless and wonderful details that could be relayed to the fellows at school. A few of them, of course, had brothers of their own in the Air Force, but none of them had Bricky, and that made all the difference. He was quite sorry for them, but most willing to share and to expound.

Gosh, he missed Bricky, but, gosh, it was worth it.

A dream crept across his mind. Maybe the war would last for years. Maybe some one of these days, a new pilot would stand before his commanding officer somewhere in Pacific territory and make a firm salute. “Lieutenant Baker reporting for duty, sir.”

His commanding officer would look up quickly from his notes. “Timothy!” Bricky would say, holding it all back. They would shake hands.

For the entire next block toward home, Timothy shook hands with his brother, but on the last block spring got into his heels and he raced the distance like a lunatic, yelling his jubilee. The porch steps he took in two leaps, crashed happily into the front hall and smacked his books and his lunchbox down on the hall table. He then opened his mouth to shout for his mother, not because he wanted her for anything specific, but because he simply needed to know her exact location.

His mouth, opened to “Hey, mom!” closed suddenly in surprise. His father’s hat was lying on the hall table. There was nothing to prepare him for his father’s hat on the hall table at three-thirty in the afternoon. His father’s hat kept regular hours. An unaccountable sense of formality descended on Timothy. He looked anxiously into the hall mirror and made a gesture toward flattening the top lock of his hair. It sprang up again under his hand, and he compromised on untying the sleeves of his sweater from around his waist and putting it firmly down on top of his books. None of this had anything to do with his father, who maintained strict neutrality on the subject of his son’s appearance. It was entirely a matter between Timothy, the time of day, and that unexpected gray felt hat on the hall table.

There were a dozen reasons for dad’s having come home early. There was nothing to get excited about. Timothy turned his back on the hall table and the hat, opened the door and went through into the living room. There was no one there, but he could hear his father’s voice in the kitchen, and, because the kitchen was a reassuring place, he felt better. He went on into the kitchen, shoving the door only part open and easing himself through it.

His mother was sitting on the kitchen chair beside the kitchen table. She was just sitting there, not doing anything. She never sat anywhere like that, doing nothing.

The formal, pressed-down feeling returned to Timothy and stuck in his throat.

He looked toward his father appealingly, but his father was leaning against the sink, with his hands behind him pressed against it, and staring down at the floor.

“Mom — ” said Timothy.

They both looked at him then, but it was his father who answered. He answered right away, as if it had to be said fast. “You’ll have to know, Tim,” he said, almost roughly. “It’s Bricky. He’s missing in action.” Missing in action. He had met the phrase so many times that it wasn’t frightening. There was no possible connection in his mind between “missing in action” and Bricky …

Missing in action. It was a picture on a movie screen, nothing more. Bricky, the invincible, would have bailed out, perhaps somewhere in the jungle. Or he would have nursed his damaged crate down to earth in a fantastically cool exhibition of flying skill, his men trusting him to see them through.

A hot, fierce pride surged up in Timothy. He wanted to tell his mother and father not to look that way; that Bricky, wherever he was, was safe. He wanted to reassure them, so that they would be smiling at him again and all the old cozy confidence would return to the kitchen.

His father was dragging words out, one by one. “The plane didn’t come back,” he said. “They were on a bombing mission, and they didn’t come back. We just got the telegram.”

An awful thing happened then. Timothy’s mother began to cry. He had never in his life seen her cry. It had never occurred to him that she was capable of it, and a monstrous chasm of insecurity yawned suddenly at his feet.

His father went over to her and got down on his knees on the kitchen linoleum, and he stayed there with his arm around her shoulders, murmuring, with his cheek against her hair, “Don’t, Ellen. Don’t, dearest.”

Timothy stood there in the middle of the floor with his hands jammed stiffly into his pockets and his eyes turned away from his father and mother. He was much more frightened by their sudden unfamiliarity than by what his father had told him. “Missing in action” was just words. His mother crying was a sheer impossibility, made visible before him.

He realized that he had to get out of the kitchen right away, because it was the place he had always been safest, and now that made it unendurable. He couldn’t do anything, anyway. Later, when his mother wasn’t — when his mother felt better, he could explain to her about Bricky being safe. He slid out of the room like a ghost, and, linked in their fear, neither of them even looked up.

In the front hall, he stopped for a moment. The spring sun outside was shining, bright and warm, on the street, and he knew exactly how the heat of it would feel slanting across his shoulders. But his mother had thought he ought to wear his sweater today. He wanted very badly to do something to make her feel better. He frowned and pulled the sweater on over his head, jamming his arms into the sleeves and resisting the temptation to push up the cuffs. It stretched them, his mother said.

He went slowly down the front steps, worrying about his mother. The words “missing in action” still meant exactly nothing to him. They were only another installment in the exciting war serial that was Bricky’s Pacific adventures, and there was not the slightest shadow of doubt in his mind about Bricky’s safe return, though he was eager for details. He guessed none of the other fellows at school had members of their family gallantly missing in action.

No, it wasn’t Bricky that made him feel funny in the pit of his stomach. The thing was he hadn’t known that grownups cried, and the discovery took a good deal of stability out of his world.

His mother might go on being frightened for days ahead, until they heard that Bricky was all right, and he would be tiptoeing around her in his mind all the time to make things better for her, and what he would really be wanting would be for things to be again the way they had been before.

He didn’t want to feel all unsettled inside. The way he felt now was the way he had felt the time they had been waiting to hear from his sister in California when the baby came. He had known quite well that Margaret would be fine and everything, but just the same, the baby’s coming had got into the house and filled it with uncertainties. Now it was the War Department. He was suddenly quite angry with the War Department. Bricky wasn’t going to like it, either, when he got back. He wouldn’t like mom worrying. Timothy wished now he had stayed a little longer in the kitchen and asked a few questions. He would have liked to know what that War Department had said, and, as he went down the street without any particular aim or direction, he turned it over and over in his mind.

He had walked back, without meaning to, to the vacant lot with the old shack on it, and it occurred to him that, while he had been shooting down those Jap planes in Bricky’s Hornet, his mother and father had been there in the kitchen. Looking like that.

He left the sidewalk and walked into the grassy tangle, scuffing his shoes through last autumn’s leaves. He would have liked some company, and he toyed for a moment with going over to Davy Peters’ house and telling him that the War Department had sent them a telegram about Bricky, but decided against it.

He sat down on the grass with his back against the wall of the shack. He could feel the rough coolness of the brown boards even through his sweater, and the sun spilled warmth down his front. It was unthinkable that the shack should ever be more comforting than the kitchen at home, but this time it was.

He wished he knew just what the telegram had said. There was something, he thought, that they always put in. Something about “We regret to inform you,” but maybe that was just for soldiers’ families when the soldier had got killed. He had seen a movie that had that in it once, and it had made quite an impression, because in the movie it was all tied up with not talking about the things you knew, and for days Timothy had gone around with a tightly shut mouth and the look of one who is giving no aid and comfort to the enemy. He had even torn the corners off all Bricky’s letters and burned them up with a fine secret feeling of citizenship, and then he had regretted it afterward, when he remembered it was only the United States APO address and no good to anyone. It was too bad, in a way, because they would have made a good collection. On the other hand, he already had eighteen separate and distinct collections, and the shelf in his room, the corner of the second drawer down in the living room desk, and the excellent location behind the laundry tub in the basement were all getting seriously overcrowded.

He wondered if maybe later he could have the telegram. He could start a good collection with the telegram, he thought. He would print on a piece of paper, “Things Relating to My Brother Bricky,” and paste it onto a box. He even knew the box he would use. It held his father’s golf shoes, but some kind of arrangement could be worked out for putting the shoes somewhere else. His father was very good about that sort of thing, once he understood boxes were really needed, and, later on, this one could hold all the souvenirs and medals and things Bricky would bring home.

The telegram, which maybe began “We regret to inform you,” would fit neatly into the box without having to be folded. It would go on with something about “your son, Lieutenant Ronald Baker,” and then there would be something more, not quite clear in his mind, about “He is reported missing in action over the South Pacific, having failed to return from an important bombing mission.”

Timothy scowled at a sparrow. There was another part that went with the “missing in action” part. Missing, believed — Missing, believed killed.

That was when it hit him. That was the moment when he suddenly realized what had happened — when the thing that the telegram stood for took shape clearly before him, not as something that had frightened his mother and made his father hold her very tight, but as something real about Bricky.

Bricky, his brother. Bricky, with whom he had sat a hundred times in this exact place and talked and talked, Bricky who went fishing with him, who showed him how to tie a sheepshank, who was going to help him build a radio when he came back.

“When he comes back,” said Timothy aloud, licking his lips because they had unaccountably gone dry. But suppose now that Bricky didn’t come back? Suppose that telegram was the end of everything?

It was the vacant lot and the shack that weren’t safe anymore. In the kitchen, he had known, without questioning it, that Bricky was all right. It was here, out in the open, that fear had come crawling. Bricky was dead. He knew Bricky was dead, and he was dead thousands of miles from anywhere, and they wouldn’t see him again ever.

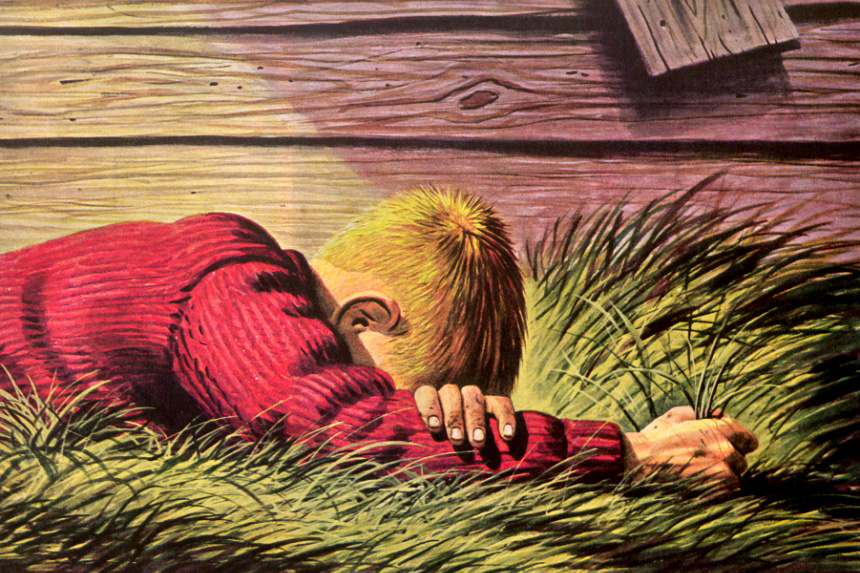

Timothy sat there, and the pain in his stomach wasn’t anything like the pain you got from eating too much or being hungry. He rocked back and forth, not very much, but enough to cradle the sharpness of it, being careful not to breathe, because if he breathed it went down too far inside and hurt too much. If he could just sit there, maybe, not breathing

He couldn’t. There came a time when his lungs took a deep gulp of air without his having anything to do with it, and when that time came there was no way of holding out any longer.

Bricky was dead. He gave a great strangled sob and rolled over on his face, sprawling across the ground, and everything that was good and safe and beautiful quit the earth and left him with nothing to hold on to. He clung to the grass, shaking desperately with fear and pain and loss, and the immensity and the loneliness and the danger of being a human rolled over and over him in drowning waves.

Behind him, the shack, which only a little while ago had been a shelter for the sneak attack of Zero planes, was immobile and solid in the sunshine. It was only a shack in a vacant lot. The tumbled weeds and vines above which The Hornet had swooped and soared were weeds and vines, not a battleground for airborne knights.

It wasn’t that way. It wasn’t that way at all. It had nothing to do with a gallant plane, outnumbered but triumphant. It had nothing to do with the Bricky who had flown in his brother’s dreams, as safe and invincible as Saint George.

A plane was a thing that could be shot down out of the safe sky by murderous gunfire. Bricky was a man whose body could be thrown from the cockpit and spin senselessly down into cold water. It was a cheat. The whole thing was a cheat.

The war — this vague big thing that moved in shadowy headlines, in a glorious pageantry of medals and flags and brave men shaking hands — wasn’t that at all. He had thought it was something like the Holy Grail and King Arthur, that it shone with beauty and was very high and proud.

And it wasn’t. It was fear and this hollowed panic inside him, and it was not seeing Bricky again. Not seeing him again ever. That was why his mother had cried.

That was why his father’s voice had been so rough and quick. And it wasn’t to be endured. He breathed in shivering gasps, there with his face buried in cool-smelling grass and earth and the sun friendly and gentle on his shoulders that didn’t feel it anymore. It would go on like this, day after day and week after week. Bricky was dead, and the place where Bricky had been would never be filled in.

That was what war was, and he knew about it now, and the knowledge was too awful and too immense to be borne. He wanted his mother. He wanted to run to her and to hold to her tightly and to cry his heart out with her arms around his shoulders and her reassuring voice in his ears.

But his mother felt like this, too, and his father. There was no safety anywhere. No one could help him, except himself, and he was eleven years old. He didn’t want to know about all these things. He didn’t want to know what war really was. He wanted it to be a picture on a movie screen again, with excitement and glory and men being brave. Not this immense, unendurable fear and emptiness. He couldn’t even cry.

He was eleven years old, and he lay there face down in the grass, and he couldn’t cry. He groped for anything to ease him, and he thought perhaps Bricky’s plane hadn’t been alone when it crashed to the flat blue water. He thought that other planes might have been blotted out with it — planes with big red suns painted on them.

But even that didn’t do any good. There were men in those planes with the suns on them. Not men like men he knew, not Americans, but real people just the same. No one had told him that he would one day know that the enemy were real people, no one had warned him against finding it out.

He pressed closer against the ground, trying to draw comfort up from it, but he kept shaking. “Now I lay me down to sleep,” said Timothy into the grass. “Now I lay me down to sleep. Now I lay me — ”

It was a long, long time before the shaking stopped. He was surprised, at the end of it, to find that he was still there on the ground. He pushed away from it and sat up, his head swimming. The sun was much lower now, and a little wind had sprung up to move the vines around him so they swayed against the shack. The sweater felt good around his shoulders, and it was the sweater that made him realize suddenly that he couldn’t go on lying there waiting for the world to stop and end the pain.

The world wasn’t going to stop. It was going right on, and Timothy Baker was still in it. He would go on being in it, and the thing inside him would go on being the thing inside him. He would have, somehow, to live with that too. He would have to go back to the house, to the kitchen, to his mother and father, to school, to coming home and knowing that Bricky wouldn’t be there.

Timothy looked around. He felt weak and dizzy, the way he’d felt once after a fever. The shack was there, with no Jap Zeros behind it. The place where he had stood when he was being Bricky and The Hornet was just a piece of ground. His mouth drew in, with his teeth clipping his lower lip, while he stared. There wasn’t any escape. He would have to go back — along the sidewalk, up the path, through the front door, into the hallway, into the living room, into the kitchen. There wasn’t any escape from his mother’s eyes or his father’s voice. He knew all about it now, and he was stiff and sore from knowing about it.

He saw what he had to do. He had to go home and face that telegram. He got to his feet. He brushed off the dry bits of grass that had clung to the blurred wool of his sweater, and he pulled the cuffs around straight, so they wouldn’t be stretched wrong. Then he walked across the grass, out of the lot and onto the sidewalk, holding himself very carefully against the pain.

He held himself that way all the distance back, and when he got to his own front yard he was able to walk quite directly and quickly up the path and up the steps. He turned the doorknob and he went into the front hall. It was getting darker outdoors already, and the hall was dim. It was a moment before he realized that his father was standing in the hallway, waiting for him.

He stopped where he was, getting the pieces of himself together. He wasn’t even shaking now, and some vague kind of pride stirred deep down inside him.

He said, “Dad” dragging the monosyllable out.

“Yes, Timmy.”

“May I see the telegram, please?”

His father reached into his pocket and took out the brown leather wallet that he carried papers around in. The telegram was on top of some letters and bills, and it was strange to see it already so much a part of their living that it was jostled by business things.

Timothy took the yellow envelope and opened it carefully. There it was. “Lieutenant Ronald Baker, missing in action.” The stiff formality of the printed words made it seem so final that he felt the coldness and the fear spreading through him again, the way it had been at the shack. His mind wanted to drag away from the piece of paper, and he had to force it to think instead.

With careful stubbornness, he read the telegram again. It wasn’t really very much that the War Department said — just that the plane had not returned and that the family would be advised of any further news. He read the last part once more. Any further news. That meant the War Department wasn’t sure what had happened. Bricky might have bailed out somewhere. There had been stories in the newspaper about fliers who bailed out and were picked up later. That was a hope. Timothy weighed it carefully in his mind, not letting himself clutch at it, and it was still a hope. It was a perfectly fair one that they were entitled to, he and his father and mother.

He held his thoughts steady on that for a moment, and then he made them go on logically and precisely. Another thing that could have happened was that Bricky had gone down somewhere over land that was held by the Japanese. If that was it, Bricky might be a prisoner of war. Prisoners of war came back. That was another hope, and it was a perfectly fair one too.

He had two hopes, then. They were reasonable hopes, and he had a right to hang on to them very tightly. The telegram didn’t say “believed killed.” Frowning, he went through it in his head again, adding up as if it were an arithmetic problem. There were three things that the telegram could mean. Two of them were on the side of Bricky’s safety, and one was against it. Two chances to one was almost a promise.

Timothy drew a deep breath and handed the telegram back to his father. His father took it without saying anything, then he put his hand against the back of Timothy’s neck and rubbed his fingers up through the stubbly hair. For just a moment, Timothy turned his head, pressing close against the buttons of his father’s coat, then he pulled away.

“Can I go outdoors for a little while?” he said.

“Sure. I guess supper will be the usual time.”

They nodded to each other, then Timothy turned and went out of the house. He went down the steps, his hands jammed in his pockets, and began to walk along the sidewalk, feeling still a little hollow, but perfectly steady.

His heart fitted him again. It had stopped pounding against the cage of his ribs, and it didn’t hurt anymore. The old feeling of safety and comfort was beginning to come back, but now it wasn’t a part of his home or of the day. It was inside himself and solid, so that he couldn’t mislay it again ever. He pushed his hair away from his forehead, letting the wind get at it. The air was cooler now and felt good, and he had a vague moment of being hungry.

Then he looked around him. He was back at the vacant shack, and the shack had been waiting there for him to come. He eyed it gravely. Behind the shack were the Jap Zeros. They had been waiting for him too. He knew they were there and that their force was overwhelming. Timothy’s fingers reached automatically for the controls of his plane. His jaw tightened and his eyes narrowed, and he opened his mouth to let out the roar of motors.

And, suddenly, he stopped. His hand dropped down to his side and his mouth shut. He stood there quite quietly for a moment, as if he had lost something and were trying to remember what it was. Then he gave a sigh of relinquishment.

His fingers curled firmly around air again and closed, but this time they didn’t close on the controls of a machine. They closed on dangling reins.

“Come on, Silver, old boy,” said Timothy softly to the evening. “They’ve got the jump on us, but we can catch them yet.”

He touched his spurs to his gallant pinto pony, and, wheeling, he loped away across the sunlit plain.

Featured image: Illustration by Stevan Dohanos (© SEPS)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This is a touching story, with a mixture of emotions difficult for anyone to cope with. This boy is to be admired for his courage and upbeat attitude given a probable, terrible outcome still unconfirmed. Since we don’t know this as a certainty, it would be nice to think his bother did come home, and it had the happy ending the family would want.