Welsh author Perceval Gibbon wrote for the Rand Daily Mail in South Africa as he regularly published stories in McClure’s, Harper’s, and The Saturday Evening Post in the early 20th century. His farcical “A Deal in Exchange” follows an accidental thief on the harsh streets of Paris as he fumbles a stack of francs. Luckily, Samuel Lawrence has coincidence on his side.

Published on July 1, 1922

Outside the Gare du Nord, upon the busy pavement of the Rue Lafayette, he stopped suddenly, a snag in the busy current of the foot traffic, and made a wide-armed gesture of furious anger and helpless despair. One of the outflung arms took a stout Parisian business man across the chest, who at first was unwilling to receive apologies. It was the offender’s meekness, his figure of a timid, rather shabby and aging man, a stranger adrift in Paris, which softened him. He grunted incoherently and strode on, leaving Samuel Lawrence to wander upon his way.

For it had come to this with him: Save for something under two hundred francs in his pocket and the clothes he stood in, he had nothing left in the world, not even the rights which are common to all men. Two days before he had been a clerk in the London office of the Beach Camera Company, poor and unconsidered enough, yet with a livelihood, the liking of some few friends, the toleration of many. And the previous day, fetching the factory wages from the bank, he had turned in one moment of dazzlement, in some grand climacteric crisis of nerves and morals, into a thief; and only an hour or two previously he had been robbed of his spoil. Nothing remained.

He wandered on. Evening was at hand and he was bitterly weary. It was needful that he should find a roof somewhere. And as he went his aching brain drummed forever on the manner of his loss. The plump middle-aged gentleman who had shared his first-class compartment with him from Boulogne — he was the gainer. When the train reached Paris the man had been prompt to get up, claim the services of a porter and pass his two suitcases through the window to him. Then briskly, like one accustomed to arrivals and departures, he had descended from the train and disappeared in the wake of his porter. It was not till he was out of sight that Lawrence discovered that the suitcase he had left behind was one of his own and the one he had taken in its place contained over three thousand pounds, the property of the Beach Camera Company.

Lawrence had charged wildly and vainly after him, only to find himself bumping into the octroi, the municipal customs of Paris. He thought at first that it was the police he had to deal with and was thrown into a panic. He came free to find himself in the street. He had not even brought away the substitute suitcase which the stranger had left behind. And he knew that he dared not make inquiries through the only channels that were likely to be fruitful. It was when he had first realized this that he had thrown out his arms in the first sincere and unfettered gesture of his life.

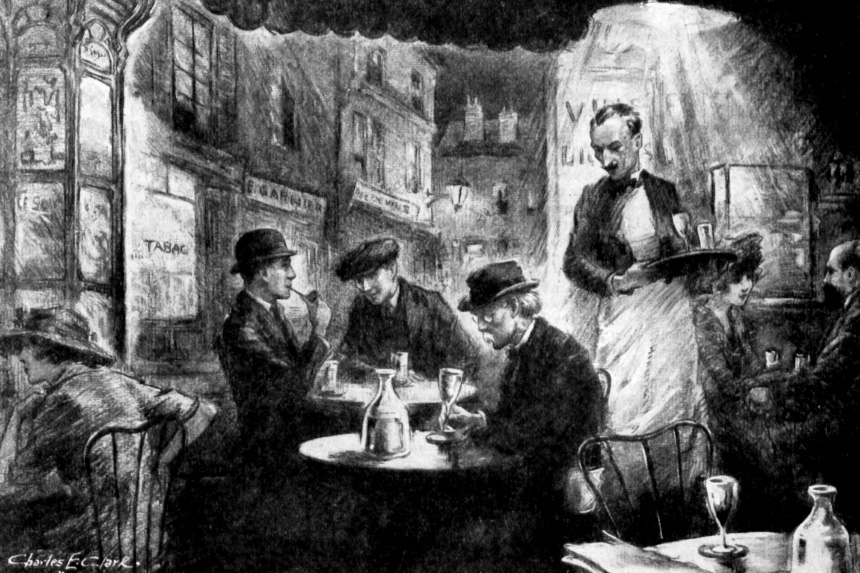

He came abreast of a café, with seats and small tables under an awning. He hesitated, but he was weary to the point where shyness breaks down, and he found himself a chair. A waiter brought him a glass of beer. He would have preferred tea, but everybody else seemed to be drinking beer, and he had not the energy to argue about it. He slouched down in his tiny iron chair to take what repose its barren contours could give him, and sat thus till an English voice at his elbow roused him to attention. It was only two young men, clerks in some English agency in Paris, chattering idly. Samuel Lawrence drank his beer and awaited his opportunity.

“Excuse me, I’m a stranger here.” The young men turned to him. “Could you kindly tell me where I can get a bed tonight? I’ve — er — lost my luggage and I want — I’m afraid I want a rather cheap bed.”

“Heaps of places,” said the youth nearest to him indifferently. “Little hotels are scattered all over the place. Of course if you want something very cheap you’d better go up to Montmartre.”

“Montmartre!” repeated Lawrence. “Er — could you direct me?”

Together they gave him a general indication of the route he must take. They were not entirely agreed about it, and disputed over it, forgetting him the while. But in the end he had a vague idea of the way and departed to grope it out.

It was scarcely stranger or more incongruous that Samuel Lawrence, bending under those stresses which are prone to bear upon the man of fifty, fearful of being discharged, suffering a little from the after effects of influenza, should become of a sudden a thief than that night, sweet with the breath of a ripe spring, should find him climbing the hill towards the more sinister slums of the quarter. He brought to that incubator of the more violent sins his mild, vague face with its gold-rimmed pince-nez, his graying mustache with its drooping ends, his shoulders that stooped with much bending over a desk. Inhabitants of the place, flitting by as noiselessly as bats or standing at ‘zinc-topped bars open to the street, turned to look at him. He passed among them, unconscious of all save his own trouble.

At a death trap of a house which called itself a hotel and produced a fat, hairy proprietor, collarless and coatless, who spoke English, he got himself a bed at last. For ten francs paid in advance he was granted a cupboard of a room, with a narrow bed in it, a deal table bearing a ewer and basin about the size of a cup and saucer, and a chair.

“It will do,” he said as he inspected it. “I am very tired.”

“You want a drink?” inquired the proprietor. “I got whisky, cognac, wine, everything.”

Samuel Lawrence shook his head.

“Not tonight, thank you,” he answered.

The gross man looked at him closely.

“I t’ink you sleep all de same,” he said, and departed.

Lawrence could never be sure afterwards whether he locked the door or not before he lay down on the stony bed in the room. Despite his weariness, it was some time before he could sleep; the ramshackle house was alive with noises. First, people below were singing; then there was an altercation outside his door between people who seemed to speak the same language as firecrackers; and then a woman screamed continuously for five minutes and thereafter sobbed rendingly. But at last he fell asleep, to wake later with an irresistible impression that he was not alone.

He found his matches and lit his candle, the room’s only illuminant. There was no one in the place but himself, and the door, which he had imagined to be open, was closed. He sat up in the bed and stared about him. He was about to put it down to a touch of nightmare when he heard the unmistakable creak of footsteps on ill-laid boards outside his door. He rose and, candle in hand, opened the door. It was not locked now at any rate. Without, the narrow passage extended to left and right; the stairs descended in the middle of it. But there was no one in sight.

He returned to his room, closed and locked the door and was about to go to bed again when his eyes fell on the clothes he had folded upon the chair. With an inarticulate cry he picked them up and hurriedly searched them, first in feverish haste, then methodically, garment by garment. Both quests yielded the same result. His pockets had not been so much robbed as gutted; it was not only his money that was gone, but everything they had contained. Not even his handkerchief remained to him.

From some church nearby a clock struck four. It was then, sitting on his bed by the light of his candle, that he knew the true quality of the life of the man who has made himself an outcast. He had no recourse; to appeal to the police or the British consul was to insure his own arrest. All hands were against him.

At eight o’clock he was dressed and downstairs. The fat proprietor, with the crumpled look about him of one who has slept in his clothes, was in the entry as he went forth. The creature gave him a grin of infinite malice and amusement.

“You sleep good?” he inquired.

Samuel Lawrence looked at him and knew himself vanquished. The creature had strength of a kind, both of physique and personality; he himself had none of either. He turned and went on down the hill.

It was a morning of the true Paris glory, with a sky of soft radiance and a balm upon the air. The freakish fate which buffeted him along took him to the grand boulevards, where the trees along the sidewalk were resplendent with tender green. He was not shaved or properly washed, and he had not breakfasted, nor was he to breakfast. He moved at a tramp’s gait through the lively crowds, reflected in all his humility and misfortune in the brilliant windows of the shops.

He could improvise no plan. He knew he was at the mercy of incalculable forces; and when it was nearing noon, and he was already footsore, the freakish fate took pity on him.

It happened near the Madeleine. He was going along the sidewalk, limping a little now, when he saw, coming in the other direction, a figure whose view made him halt with a gasp. A plump and prosperous figure it was, with a high-held, serene and debonair face under a gray Hamburg hat, sprucely tailored, with a neat pomaded mustache. It was the stranger of the train, the man who had taken the wrong suitcase.

The man passed him. Samuel Lawrence came round as on a pivot; then in an access of energy followed and overtook him. He touched him on the elbow.

“Excuse me,” he said nervously.

The other spun on his heel, and it seemed to Lawrence that an immense relief showed upon his face at the sight of himself. Then it darkened.

“What the devil d’you mean by layin’ hold of me like that?” demanded the stranger.

“I beg your pardon for startling you,” said Lawrence. “But I believe you took my suitcase from the train yesterday in mistake for your own.”

The face before him cleared up.

“Oh, it was yours, was it? Yes, I recognize you now. Why didn’t you come after me? I found my case all right, but I couldn’t see a trace of you.”

Lawrence explained. The well-fed stranger nodded.

“Well,” he said, “your case is all right. I left it in the consigne — the cloakroom, that is. But like a silly fool I found this morning that I’d lost the ticket. Still, you can get it all right.”

Lawrence trembled. Then the case and its secret were still intact.

“Would you kindly tell me how I should proceed?”

“Certainly,” said the other. “It’s easy enough. You go to the consigne, you know; and you claim it. You’ll have to prove your identity and all that in the usual way, and describe the contents of the thing. Then you open it, and when they’ve checked your description they hand it over to you.”

“Oh!” said Lawrence; and presently, “Thank you.”

“I’ll drive up with you now and see you through it if you like,” volunteered the other.

Lawrence shook his head hopelessly. He became suddenly aware that his chance-met acquaintance could develop a peculiar steely piercingness of gaze. The bland and healthy face was in a moment acute and formidable.

“No?” said the stranger. “All right! But come and have a drink. I want to talk to you.”

And when Lawrence still hung back he added startlingly, “Better come, Mr. Lawrence!”

Lawrence collapsed and surrendered. He suffered himself to be led away.

“Are you a detective?” he gasped.

The other considered as if uncertain whether he were or not.

“No,” he finally decided. “Nothing of the kind. Your case is in the London papers this morning. That’s how I knew your name.”

Seated upon a plush bench in the interior of a café, with whisky and soda before them, they talked.

“An’ the boodle is in that case?” said the stranger. “Three thousand-and-odd of the best — and I took it by accident and put it out o’ reach. Me! Well, we got to get it somehow.”

“What did the papers say?” faltered Lawrence.

“Oh, them! Seems your camera people are suspecting anything from the truth to loss of memory. Seems to me they trusted you pretty far. But never mind about that. What have you been doing since yesterday?”

He was persistent, and soon he had the full story of Samuel Lawrence’s first night in Paris. He laughed.

“I shall have to look after you a bit,” he declared. “At any rate until we get that bag. But the first thing for you is a bite of lunch. Garcon!”

“But,” hesitated Lawrence, “are you — er — ”

“Go on!” encouraged the other. “Say it! Am I a crook? Is that it? Why, of course I am, and a good one — not a bloomin’ beginner like you! My name’s Neumann; Pony Neumann my friends call me; an’ you’re lucky to have run across me. Ah, here’s the menu.”

It was an admirable lunch which Mr. Neumann selected, satisfying yet delicate, at once stimulating and rewarding the appetite; and as they ate he talked.

“That damn ticket!” he philosophized. “Suppose I wasn’t very careful where I put it, the case not being mine; and so it goes and loses itself. I’ve known men hanged or guillotined through accidents as little as that. And think o’ that thing blowing about in the gutter Just as if it warn’t worth better than three thou! There’s romance for you! Take some more o’ this wine.”

Lawrence sighed.

“I put it in my overcoat pocket,” said Mr. Neumann. “Then I suppose I pulled out my gloves or my cigar case and it went adrift. I searched that coat this morning and all I found was a ten-centime piece that had somehow got into the breast pocket. I searched the suit I’d been wearing, too, but nothing doing.”

“Then how” began Lawrence.

“Ah!” said Mr. Neumann. “That’s what I’ve got to think out. But whatever I arrange, you’ll have to be on hand. You see, I was fool enough to explain at the consigne that I’d taken the thing by mistake. So you’ll be wanted. Where are you going to stay?”

Lawrence smiled weakly.

“I’ve got no money,” he reminded Mr. Neumann.

“Ah, but you have!” retorted that financier, reaching into his bosom. “You’re an investment, my boy. See this? That’s a thousand-franc note, that is, an’ I’m goin’ to invest it in your expectations. An’ you better get a shave an’ a bath right away. An’ look here! You find a place to stay, an’ meet me here tomorrow at the same time, eh? An’ now you better bump along.”

Lawrence rose obediently. There was no part in this conversation that he was competent to sustain, and obedience was his only course. A waiter ran to help him with his coat and hand him his hat.

“All right, I’ll tip him,” said Mr. Neumann over the cigar which he was lighting. “Tomorrow at the same time, remember!”

“Tomorrow at the same time,” repeated Lawrence mechanically, and took his departure.

The barber’s at which he got himself shaved and his hair brushed demurred a little at changing a thousand-franc note, but achieved it in the end. Lawrence tipped generously.

“Thank you,” he understood the barber to say in French. “And here is M. Neumann’s hat.”

“Eh?”

The barber smilingly turned the hat over, as one who has played a clever trick, and lettered in gilt upon the leather sweatband within, plain as a sign post, was the name P. Neumann.

“They gave me the wrong hat,” said Lawrence.

He took it, however, and stood with it in his hand, undecided whether to return with it at once to the cafe or postpone it till tomorrow. It was a smarter hat than his own. He saw the corner of a piece of green paper sticking up from inside the sweatband and plucked it out.

“Ah,” said the barber. “Un billet de consigne!”

He recognized the word consigne and gasped. It was, it must be, the lost cloakroom ticket. Mr. Neumann had put it in his hat instead of in his pocket and forgotten it. He startled the barber by uttering a loud cry and dashing from the shop.

That afternoon the Beach Camera Company received a telegram from Paris which startled them considerably. It said:

“Am here. Money intact. Returning tonight.

SAMUEL LAWRENCE.”

And in the end loss of memory was held to be the true explanation. Mr. Neumann, however, had another word for it.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now