Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

It’s Halloween, and as the young folks say, tonight is gonna be lit. Especially if you’re a jack-o’-lantern. Those kooky carved pumpkins will be glowing all across the country tonight, revealing weird, funny, and grotesque faces. And while everybody is familiar with the jack-o’-lantern, how it got its name is something of a mystery. There are competing stories.

What all the stories agree on is that these Halloween pumpkin faces weren’t the first things to be called jack-o’-lanterns. It’s a shortening of jack of the lantern, and at one time it referred to actual people. In 17th-century Britain, Jack-o’-lantern was a slang term for a night watchman — or any man carrying a lantern. At the time, Jack was a common term for any unknown man, similar to guy today — we also see it in the phrase “jack of all trades.” So a night watchmen, who would be carrying a lantern around for light, would be a Jack of (or with) a lantern.

Now imagine you’re out at night trudging through a marshy area — maybe even for some nefarious purpose. Out in the dark, you spy a bright, flickering flame low to the ground. You might at first think that some night watchman is following you — that it’s some Jack with a lantern. When you realize the flame isn’t getting any closer, you investigate and discover that the flame is coming directly from the ground. Gas from decomposing organic material has spontaneously caught fire.

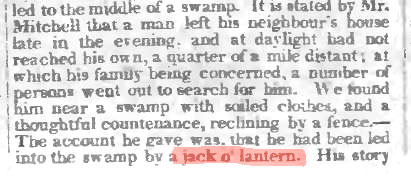

This phenomenon of light appearing over marshy ground is called in Latin ignis fatuus (plural ignes fatui) — “foolish fire” — but is more commonly known as either will-o’-the-wisp or, you guessed it, jack-o’-lantern. This was the reference in the first appearance of jack-o’-lantern in The Saturday Evening Post, in the February 4, 1832, issue in an article called “Ignes Fatui.”

Night watchmen weren’t the only Jacks with lanterns either. There’s an old Irish story about a man called Stingy Jack. Stingy Jack was not a good person, always cheating and swindling people. He was so good at it, though, that he managed to trap the Devil himself up a tree. Not one to pass up an opportunity to enrich himself, Jack made a deal with the Devil: In exchange for the Devil’s freedom, Jack’s eternal soul would not be condemned to hell when he died. The Devil agreed, Jack let him down, and they continued on their wicked way.

When Jack eventually died, he arrived at the gates of heaven — but he had been such a horrible person that God wouldn’t let him in. He was sent to hell, but the Devil kept his word and wouldn’t let him in there either. The Devil tossed him an ember from the infernal pits and sent him off into the night. Jack carved a lantern out of a turnip — his favorite food, he always had one with him — to hold the ember and light his way. Thus, Stingy Jack became Jack of the lantern — or Jack-o’-lantern.

The introduction of a turnip into the story might seem odd to some, but remember: The pumpkin was a New World plant and wasn’t available in Ireland for centuries. Before the pumpkin, Celtic pagans in Ireland and Scotland carved grotesque faces into turnips and beets to ward off evil spirits during their celebration of Samhain. (These probably weren’t called jack-o’-lanterns, though.) Samhain traditionally begins on the evening of October 31, and many of today’s Halloween traditions — the dressing up, the trick-or-treating — stem from Samhain.

It is no surprise, then, that the appearance and growing popularity of pumpkin-based jack-o’-lanterns in the United States coincided with a rush of Irish immigrants to these shores in the 19th century. Turnips were harder to find in America, and pumpkins — larger, easier to carve, and easy to grow — must have seemed like the perfect replacement. And through some combination of connections between night watchman slang, ignis fatuus, Celtic tradition, and Irish folklore, the modern jack-o’-lantern got its name.

Featured image: SEPS

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Well Andy, the only thing that better be lit out my way this evening are flashlights. The fire departments in Ca. are maxed-out to put it mildly as everyone knows. Interesting how ‘Jack’ was a slang term for a guy at one time.

Interesting too on the “Ignes Fatui”. I’d never heard of this term before, but had of organic material spontaneously catching fire a number of years ago. I knew a co-worker whose grandfather was in a nursing home, and he was found charred, in his burned bed with nothing else burned. They were told it was spontaneous combustion; that it’s very rare, but does happen. I didn’t know about Samhain before, so this is the appropriate day to learn about it.

Thank you so much- knew about Samhein, didn’t know this curious story line! How hot you are for this little bite!!