No moral intuition is more hardwired into Americans’ conception of economic justice than equality of opportunity. While some of us may be rich and others poor, we are willing to accept such outcomes as long as everyone has an equal shot at success. The moral legitimacy of the market’s distribution of income rests on a presumption that our system rewards ingenuity, hard work, talent, and risk-taking rather than race, class, family connections, or some other advantage we consider unearned, illegitimate, or unfair.

“In every wise struggle for human betterment, one of the main objects, and often the only object, has been to achieve in large measure equality of opportunity,” declared President Theodore Roosevelt in a speech in Osawatomie, Kansas, in 1910, laying out the “square deal” he believed was due to all Americans.

In a speech later that year, Roosevelt took pains to reassure members of the New Haven Chamber of Commerce that his notion of equal opportunity fit squarely within the context of a market economy. “I know perfectly well that men in a race run at unequal rates of speed. I don’t want the prize to go to the man who is not fast enough to win it on his merits, but I want them to start fair.”

For the first time in American history, the steady march toward greater equality of opportunity seems to be headed in the opposite direction.

Equality of opportunity, of course, taps into the conception Americans have of themselves as a people who fought one war to shake off the tyranny of a British monarchy and aristocracy and another to shake off the chains of slavery, a people who welcomed wave after wave of ambitious immigrants yearning for a better life. Yet there is now a sizable and growing body of evidence that, despite elimination of most legal barriers to equality of opportunity, the luck of which parents you were born to continues to play an outsized role in determining economic success. Whether it’s by way of the genes we inherit (nature) or the circumstances in which we are raised (nurture), the results of this parental lottery are more important than ever in determining our natural capabilities and the degree to which we are able to develop those capabilities and bring them to an increasingly competitive marketplace. Indeed, for the first time in American history, the steady march toward greater equality of opportunity seems to be headed in the opposite direction.

Our education system is no longer serving its historical role of equalizing economic opportunity and increasing social mobility. Rather, it has become an instrument by which children lucky enough to be born into favorable circumstances increase their economic advantage over those who were not.

It was 65 years ago that the Supreme Court, relying largely on evidence and expert opinion from social scientists, ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that sending black children to separate schools was inherently unequal. Now it is time to extend that constitutional principle and declare that it is no longer acceptable to organize and finance public education in a way that segregates poor children in separate schools.

Because of our reliance on local property taxes to fund public schools, and public school systems that organize schools around residential neighborhoods, we have a system that in many places provides less funding, less effective teachers, and worse facilities to poor students who require more resources and better teachers to reach comparable educational goals. Moreover, there is clear evidence from social science research that segregating poor children in the same schools deepens their disadvantage. The only practical way to end this class segregation in education is the same way racial segregation was ended — with a Supreme Court finding that segregating poor students in the same schools denies them the equal protection of the law guaranteed by the Constitution.

As it happens, the Supreme Court explicitly rejected that view in 1973 in a case that few remember today, San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez. In a 5–4 ruling, the Court — which only two decades before, in Brown, had recognized the importance of public education to a democratic society and a child’s success in later life — reversed course and declared that public education was not a fundamental right under the Constitution. It also found that discrimination on the basis of class did not warrant the same strict scrutiny as discrimination on the basis of race. Writing for the majority, Justice Lewis Powell worried that if public education were to be treated as a fundamental right, the Court would find itself on a slippery slope that would also require it to give similar status to housing and medical care.

It is time to revisit those issues. One reason is new evidence from social science studies showing that the socioeconomic characteristics of a child’s classmates are a better predictor of educational achievement than a child’s own socioeconomic background. Another is the change in case law. In the intervening years, there has been a long line of Court decisions striking down affirmative action plans at universities or guaranteeing parents control over their children’s schooling, in which the Court’s conservative majority recognized something that sounds very much like a constitutional right to education. With a series of education reform bills, Congress has also established a strong federal interest in ensuring that all students attain minimal levels of educational achievement, with a particular emphasis on low-performing students and school districts. All of these developments provide a solid legal basis to ask the Court to reconsider the issue and declare that Rodriguez was wrongly decided.

There is nothing sacred about the idea that municipalities and school districts have to have the same boundaries, or that public education needs to be funded primarily through property taxes. To assure equal access to an adequate education, the federal courts could require states to redraw school district boundaries in ways that would end desegregation by class and put rich and poor students in the same school systems. Courts could order states to devise statewide funding formulas that would begin to break the pernicious link between local property values, per-pupil spending, and educational achievement. And judges could even insist that the newly redrawn school districts rely on student choice for school assignments and make extensive use of magnet schools.

I don’t underestimate the political and legal difficulties in bringing about such a radical restructuring of public education. I am old enough to remember the bruising battles over busing, and I am aware that the process of bringing racial integration to public schools has hardly been a smashing success. Class integration would be no less challenging, but it is also no less of a moral imperative.

It is worth recalling that the campaign to overturn the separate but equal doctrine in Plessy v. Ferguson energized a generation of Americans in the 1960s. Overturning Rodriguez and establishing the fundamental right of all children to a decent education could be the legal issue that energizes a new generation eager to ensure that history continues to bend toward justice. It will take patience, persistence, and political courage, but this is the kind of defining moral issue that is worth the effort.

From Can American Capitalism Survive? by Steven Pearlstein, copyright © 2018 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.

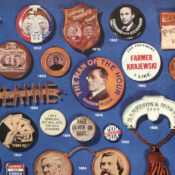

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I so wanted to address this issue—and now I have the opportunity to do so. I am a retired teacher–having taught for 44 years. I feel passionate about the diversity and equal opportunity that should be inherent in our public school system. I agreed with every point that was made by Pearlstein. He is right–it is a defining moral issue. But I did not see any mention about “open enrollment.” In Ohio—this has had a detrimental effect on our public schools. Oh yes, I know all about that “freedom of choice” argument…but when parents choose different environments for their children, they are in effect segregating our schools on a class bias. And then, sad to say, these very parents do not always vote funding for the local school that they have chosen to leave. This decision is often based on peer preference rather than any particular disappointment in the school that they are rejecting. Another issue is that the tax dollar follows the student. I understand the defensible decision for state money to go with the student—but when I vote to support my local school I want my money to stay in the district.

Thank you for this sounding board–and thank you for your wonderful and honest and I hope inspiration and lifie-changing presentation of this very important issue!

More public money is NOT the solution, anywhere, for anything.

This has been known for decades!! In Seattle and Washington state at least.

Washington state schools have relied on school levies to fund schools for decades. The huge disparity between rich and poor is most evident here, in the (as Franklin Roosevelt used to refer to us) Soviet State of Washington.

I taught in poor Seattle schools in the 70’s. We had old dirty, worn down deprived schools. As a Soecial Ed teacher working in primarily black urban schools, we had nothing. Wages were pitiful, we had no supplies, students had just started being bussed, teachers had to buy supplies – pitiful.

One summer I took a reading specialization class which was held across the lake in Bellevue – where all the rich white folks fled and lived (still do – not a coincidence that Microsft HQ is next door to Bellevue).

I was shocked. Beautiful sparkling buildings with PENCILS(!) and at the elementary school where we met for class, they had a reading specialist – FOR ONE SCHOOL! Not one reading specialist for a dozen schools but for just one ELEMENTARY school. And hold your drawers: she had a Doctorate! Hold the phone! And your drawers. I thought I would faint when I heard that. God only knows how much she was making but far more than the $6500 a year we poor folks in Seattle made.

Changed since then? Was8state just settled a lawsuit to guarantee equal funding for all students in all schools in all of Washington. Except: true to the rules of Animal Farm, all are equal but some are more equal than others.

Legis8gave the money finally, which the teachers all immediately took by striking until they hot 20+% raises across the state. So, how did the districts get the money for pencils – again – ? – you guessed it LEVIES! So back where it all started in the 70’s and the now filthy rock with Amazon kajillionaires in Seattle have their pencils but not enough computers to guarantee each student has at least four iterations.

Many of the worst schools in America receive the most amount of funding per student. The lack of respect for teachers causes some teachers to choose schools outside of the inner cities where families appreciate quality of education. Parental involvement in school is also an important immigrants from China India and for size importance of education at home in support of all the schools their own children bought it. Throwing money at the problem never. Attitude of respect for Education our key to success.