William Fay was a short story writer for the Post in the mid-1900s. His hard-boiled detective stories echo the fashionable trends of noir storytelling. In “The Thieves of Christmas Eve,” detective Wilbur Gilhouly is down on his luck and about to be demoted if he can’t crack a case before Santa is due.

Published on December 24, 1949

Wilbur Gilhouly, the detective, stood on Thirty-ninth Street, in Manhattan, pondering a problem of justice. He, for one, did not believe that a bookmaker known as Willy Kleebs had dropped a fellow man into the incinerator of the Hotel Marshall Arms. No matter what the lieutenant said, it just didn’t sound like Willy, and it was certainly not in the Christmas spirit.

The wind blew futilely against the stanch facade of Detective Gilhouly on this afternoon of December twenty-fourth. Were he not preoccupied with duty and the plight of Willy Kleebs, he would have listened to the tinkling of the bells — church bells, Salvation Army bells, and possibly, if the lieutenant’s uncharitable remarks of an hour before were true, the bells in his own head. Lieutenant Decker had a sharp and frequently unsheathed disposition that was a heavy cross to bear.

A uniformed cop named McEvoy came along. “You don’t look happy, Wilbur,” McEvoy said.

“If I been wearing a strained look, Charlie, it’s because I been thinking. An’ because I promised my missus I would do my Christmas shoppin’ early.”

Officer McEvoy swung his arms rather briskly to keep warm. “Ain’t it true,” he asked, “that Willy give that tax agent a tough time of it last week?”

“Why, yes … in a way,” said Wilbur.

Willy Kleebs, as a matter of record, had heaved Tax Agent Albert Haskins from the revolving door of the Hotel Marshall Arms, where both of them lived, to the curb of Thirty-ninth Street, in his own exuberant way. Likely enough, Tax Agent Haskins had been trying to shake him down, and Willy Kleebs, who ran his horse book with a mystic honesty exceeded only by St. Peter at the Gate, did not shake easily. But murder? No! Wilbur shook his head.

McEvoy said, “There isn’t a case against him?”

“I didn’t say that, Charlie.”

Because there was a case. There seemed no doubt Tax Agent Albert Haskins had been missing from his office and the Marshall Arms for several days, and just as little doubt that he had left a note for his wife, alleging that he had been threatened by Willy Kleebs, and directing that should evil things befall him, she should mention this to the police.

“And how about them bloodstains, Wilbur?”

“Listen,” Wilbur said, “a healthy man can put a bloodstain on half the furniture and rugs of the Marshall Arms. All he’s got to do is stick himself in the arm. Of course, I’m not sayin’ that’s all there is to it, Charlie … not after this morning.”

“That’s when they found the bridgework?”

“This morning, Charlie. At eleven-oh-five.”

“In the incinerator?”

“Hell, no; they haven’t even got the grates cool for the lab men yet. Haskins’ upper plate was found by the assistant superintendent three days ago on the basement floor … right near the manhole cover of the incinerator. But it’s only when he reads in the papers all this stuff about Haskins bein’ threatened by Willy and the fact that the guy is missing, that suddenly he wonders about them teeth and walks over to the station house this Aye Em.”

“The teeth belonged to Haskins?”

“Identified by his dentist, yes, with charts to prove it. An’ there’s blood on the incinerator cover — half washed away, careless like, so that some of it shows up under the glass. Same type as in the apartment, an’ there’s stains in the freight elevator too. It’s the self-service-push-a-button type, you know, and the lieutenant, with his big brain well, naturally, he’s got Willy takin’ the corpse down in the middle of the night — that wouldn’t be too hard — an’ dumpin’ it through the manhole cover. The upper plate? That’s one of them little ironies that murderers have to put up with, the lieutenant says. Mr. Haskins’ upper plate, accordin’ to him, just dropped out unnoticed while Willy was luggin’ the body.”

“Well,” said Officer McEvoy, “I got to shove off, Wilbur. Merry Christmas, if I don’t see ya.”

Wilbur cased the crowd for larceny and lighter mischief with that celebrated eye and memory for faces that had once caused police reporters to refer to him as “Elephant” Gilhouly. Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan, his driver, drove up in the squad car. He was young, unburdened by responsibility, and in possession of a brooch for his girlfriend. It was a lovely item, worth a month’s pay anyhow, and Wilbur reflected, without bitterness, that in his own position, as the loving husband of one and the doting father of four, he had to face the fiscal realities. He had eighty-seven dollars and forty-three cents, and a stern note from a finance company whose kind facilities it had never been his intention to abuse.

“I think maybe I’ll step over to Jablonski’s for a minute,” Wilbur said. “Don’t take any wooden lieutenants; we got one already.”

At Jablonski’s Junior Joyland, Wilbur, on tiptoe, caught the attention of Mr. Jablonski. Mr. Jablonski, who gave a substantial discount to cops and firemen, said, “I got it,” and passed to Wilbur, over people’s heads, $28.74 worth of railroad, in a box — $28.74, that is, with the discount. “What it cost me,” said Mr. Jablonski.

The trains were for little Wilbur, nine. He bought a doll’s house then for his daughter Mavis, a puppet show for Agnes-Mae, and a construction set for Edwin. And then, because — well, because love still beat more strongly in his breast than prudence, he went to a division of Jablonski’s Junior Joyland known as Mommy’s Mart, and made a twenty-two-dollar down payment on a portable, kitchen-size washing machine for Myrtle, his wife, and the one true love of his life. He would call back for the washing machine, he explained to Mr. Jablonski; the other packages he’d take.

“This is a general clearance or you would not of got such bargains,” said Mr. Jablonski. “We will be open till midnight. Come in again; tell your friends.”

Wilbur, with his packages chin-high, moved bravely toward the sidewalk. Jablonski’s, he noted, though a humble establishment, was graced by a better upholstered and more firmly bearded St. Nicholas than most. Wilbur found this somehow reassuring, though his vision was limited. He walked into a mailbox and his packages tumbled. He bent to retrieve them. He heard a mirthless and familiar voice.

“Santa’s li’l’ helper?” someone said.

Well, that was Lieutenant Decker for you. Always the sarcasm, be it Christmas or doomsday.

“What’s your explanation, Gilhouly?”

Wilbur tried to smile. He indicated the packages. “I’m just mindin’ these things for some friends, lieutenant.”

“What friends?”

“Well, my kids,” Wilbur said, then met the other’s cold gaze more steadily. “My kids are my friends,” he said with pride. The truth, after all, was a matter precious to Wilbur.

“You’re a wise guy, Gilhouly?”

“No, sir.” He placed his packages in the squad car.

“Well, Gilhouly,” Lieutenant Decker said. “against my better judgment they set bail for Willy Kleebs. You an’ that judge down at Special Sessions should have your skulls scraped.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You an’ Kleebs was always pretty chummy, Gilhouly. How well did you know him?”

“I’ve known him both in line of duty,” said Wilbur truthfully, “and after hours. I locked him up four times for makin’ book, and he is Agnes-Mae’s godfather. Look, lieutenant, have you checked the guy’s wife?”

“I personally put through the check on the widow, Gilhouly. A fine-type woman. Unimpeachable. A Vassar girl. We had a nice talk about some cultural matters … Take that silly grin off your puss!”

“Yes, sir.”

“Here are your orders, then. Kleebs right now is next door in the Marshall Arms Barbershop for a several-times-over. I want you to watch every place he goes, with regular reports to me. You an’ Kaplan, don’t let him out of your sight! That clear, Gilhouly?”

The lieutenant strode indignantly away. Wilbur and Kaplan moved over to the barbershop window. Willy Kleebs appeared to be taking the full six-dollar treatment in the No. 1 chair. He waved gaily to Wilbur and Kaplan.

“He never dropped nobody into no oven,” Wilbur said.

“Howja do at Jablonski’s, Wilbur?” Kaplan asked. “Any good?”

“Take a look for yourself. There’s nothin’ like havin’ a family, my boy. Take a look in the back of the car.”

In the No. 1 chair, Willy Kleebs wore a look of deep content. Good old Willy, always smiling — good times, bad times, always the same old Willy. Kaplan called to Wilbur from the curb.

“You put them in the back of the car? What car?”

“Right there. In the back.” He walked over to the car, looked in. The back of the car was empty.

“They ain’t here,” Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan said.

Wilbur smiled weakly. It was a joke. I’m laughing, Wilbur thought. But the brutal truth prevailed.

“Gone,” said Kaplan. “Like I toldja.”

“Eighty-one dollars,” Wilbur said. His senses reeled. Jablonski’s Santa Claus kept ringing his bell and chewing his gum. Wilbur, a tall man, turned dismayed eyes on the multitude. He saw no one sprinting through traffic with a doll’s house and assorted lumps of joy. He wanted to cry. This was Gilhouly, the good provider, with six dollars and some cents remaining, and a week late with the finance company. This was Gilhouly, the —

“Wil-bur-r-r!” Kaplan called from the plate-glass window of the barbershop. Wilbur walked over. “Look,” said Kaplan.

The No. 1 barber chair was empty. Willy Kleebs was gone.

…

It was not easy in the station house to stand before your fellow officers while Lieutenant Decker peeled your dignity away — artfully and easily, like the skin of a scalded peach.

“I always knew you were a whale of a fellow, Gilhouly,” the lieutenant said. “I could tell it by the blubber in your head.”

Less loyal comrades snickered; others looked away. The lieutenant was in the process of enjoying himself.

“I would say, Gilhouly, that it’s gonna be strictly brass buttons an’ blue coat from here in. Staten Island, maybe, or the Bronx frontier, where we can push you inta Yonkers.”

Wilbur dropped his eyes. You took it, that was all. He could remember the last time he’d been threatened with a return to uniform. His wife had stemmed her tears. “Wilbur,” she had said with priceless loyalty, “you look beautiful in blue.”

Early-winter’s darkness was over the town as Wilbur left the station house with Kaplan. Lights were everywhere, though it was only five o’clock. They came to where the squad car still stood parked before Jablonski’s.

Wilbur was watching Jablonski’s Santa Claus, whose face he had not had a chance to view at leisure until now. He stepped closer, examining minutely, and with small attempt at politeness, Santa’s rosy cheeks. Into operation came the old Gilhouly intuition. Wilbur moved and Santa jumped. Wilbur caught old Santa by the beard.

“Legomme!” Santa shouted.

But Wilbur clung tenaciously. He pulled the beard the length of the elastic, then let it snap.

Old Santa howled. “Legomme! Cudditout!”

It was not really Santa. It was a man named Mutuel Minskoff, who worked for Willy Kleebs. “What I thought,” said Wilbur.

Mutuel Minskoff was a bookmaker’s runner, which is no kind of Santa Claus at all, but one who takes bets on horses. Wilbur shook Jablonski’s Santa Claus.

“Where’s Willy Kleebs?” he demanded. “Where’s them packages you stole out of the car?”

“Honest, Wilbur — honesta me mother’s grave, I don’t know what you’re sayin’!”

Wilbur, with Kaplan’s assistance, pushed Mutuel Minskoff into the car. Wilbur stretched the beard’s elastic its full, intimidating length. “You gonna tell me?”

“We have little or nothing to say to one another,” Mutuel said with dignity, “except that I don’t like your attitude.”

Wilbur let the beard snap. He was not a man disposed toward cruel means of persuasion, but he was nonetheless determined.

“Let’s get it straight, Minskoff,” Wilbur said. “A fifty-dollar-per-diem wise guy like yourself don’t become a ten-dollar St. Nicholas because he likes to get stuck in chimneys. Well, do you?”

“This is our slack season, Wilbur.”

“Never mind that. Where is Willy Kleebs?”

“He went to visit his ninety-three-year-old mother in the Bronx.”

“Where’bouts in the Bronx?”

“That’s one of those things Willy has always kept to himself,” said Mutuel Minskoff, “an’ the little old lady don’t know he’s in trouble with the cops, you understand? In fact, she thinks that Willy’s in the feed-an’-grain trade.”

“You’re lyin’, Minskoff,” Wilbur said, but he did not really believe the man was lying. It sounded like Willy, all right. He restrained Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan from snapping the beard again. “I’m asking you, Mutuel, Number One — who stole my packages? I am asking you, Number Two — why you been standing all day in front of Jablonski’s making like an elk driver?”

“As for the packages, Wilbur, believe me, I dunno. As for Point Number Two, I’ve been watchin’ for Tax Agent Haskins. Willy didn’t kill ’im. I been waitin’ here for Haskins because we know he’s got to come back.”

“Come back for what?”

“Haskins made one mistake, Wilbur. Just like he dropped his upper plate next to the incinerator on purpose, he also drops somethin’ else in Willy’s suite, but not on purpose.”

“What did he drop?”

“He dropped his safe-deposit-box keys, Wilbur. A whole ring o’ them, he dropped. You get it? Haskins is a crook. An’ where does a crook with a big wad o’ dough an’ a small pay check hide this embarrassin’ disparity of means? In safe-deposit boxes, don’t he? In eight different banks, under eight different names.”

“You know this? You’re not lyin’ to me, Minskoff?”

“Here,” said Mutuel Minskoff, “are the keys. Understand, they’ve just got numbers on them an’ we don’t know what banks, an’ we don’t know what names this guy is usin’. All we know is he has got to get them keys.”

“Why didn’t Willy come to the police with these?”

“Willy sees that with Decker on the case, an’ blabbin’ like he does, there might be talk in the papers the cops have got a certain set of keys, an’ this Haskins will just take off like a bluebird. Willy would like to catch Haskins himself. Willy is an honest man what pays his taxes, but this guy not only tries to shake ‘im down, he owes ’im maybe twenty grand on horse bets.”

“Tell more, Mutuel. Tell all.”

“Well, Wilbur, we figured that Haskins, the crook, wanted to lam for liberty before the tax department caught on to the size of his personal assets. So what’s a better way to get off with a bundle o’ dough an’ not be tailed than to have yourself declared murdered? That’s why he sets up this frame about Willy, an’ why your friend, the lieutenant, begins to drool about maybe he can have Willy measured for that warm chair up in Ossining. You get it?”

“It happens also to have been my personal theory,” said Wilbur modestly. “Except, of course, I never knew about the keys. You better hand ’em over to me like a good boy, Mutuel. Thass right. Now get back on the job; keep ringin’ that bell … And, Kaplan,” he said, “you keep an eye on Santa.”

This was Gilhouly, the hound of justice, on the scent. The Hotel Marshall Arms, set in the shopping district of New York, was vast, commercial, and of wholesome reputation. In the plaza, as he entered, Wilbur rejoiced at the Christmas tree that rose gigantically for several floors — its glowing lights bespeaking warmth and good cheer in a cold and unbelieving world. Willy Kleebs’ suite, where Wilbur thought a little look around might help, was on the seventh floor.

“Where’s the cop they had watchin’ this suite?” he asked the bellhop who let him in by means of a key.

“The lieutenant said there was no pernt to it,” the bellhop reported. “The lieutenant sent ’im after bundle snatchers.” The bellhop, with a taste for police procedure, hovered.

“Blow,” said Wilbur. “Get lost, sonny.”

Wilbur closed the door behind him and was immediately aware of another’s presence. A woman wearing an apron and a somewhat guilty look was dusting, or at least appeared to be dusting, in the sitting room. “This place is under surveillance,” Wilbur said. “Who are you?”

“Why, Mr. Kleebs always lets me have a key to do the cleaning,” the lady said. Her apron was ruffled and unspotted. She had a way of placing hands on hips that bespoke some gayer setting and invoked old memories of action that had nothing to do with dustpans. She looked more like a cupcake to Wilbur than she looked like somebody’s mother rubbing honest knuckles raw. “If you’ll excuse me — ”

“One minute,” Wilbur said. The files of his memory were opening. “Hold on, lady.” He could smell clams, somehow. Why clams? Coney Island? No, it wasn’t Coney Island. Brighton Beach? Not Brighton either. Then it snapped. It came to him. “Hello, Kitty,” Wilbur said.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Gypsy Kitty Klein, from Rockaway Park. Used to tell fortunes for a thief named Hennessey. Must be fifteen years since I locked ’im up. You lookin’ for something, Kitty?”

“Officer,” said Gypsy Kitty, “you are playing the wrong trombone. Now, if you don’t mind — ”

“Lookin’ for some safe-deposit-box keys, Kitty?” Wilbur was swinging in the dark, but batting rather well. The proper button had been pressed. “You couldn’t by any chance be Mrs. Albert Haskins, could you? The Vassar girl? The little widow who had the nice cultural chat with the lieutenant?”

“As a matter of fact, I was really only — ”

“Don’t apologize, an’ don’t get excited, Kitty, because — well, about those keys; Homicide ain’t even heard o’ them. Me, Gilhouly; I got the keys, an — ”

“Don’t move, Gilhouly! Stay where you are!” The voice was authoritative. Wilbur did not move. Albert Haskins, with a .38 revolver, spoke distinctly, even minus his upper plate. Wilbur did not move, because his own gun lay deep in the cold-weather bunting he had neglected to unbutton. “Hands higher, Gilhouly … Frisk him, Katherine,” said Haskins to the cupcake.

Mrs. Haskins unbuttoned Wilbur’s winter ulster and rapidly divested him of firearms. She went through his jacket and its inner pockets, searching for the safe-deposit keys, without first having cased the crumpled overcoat that lay on the floor.

“Take off your jacket,” Haskins ordered. “Now your shirt.” Haskins waved his revolver convincingly. “Your pants, Gilhouly!” he commanded.

Wilbur, standing in his underwear, said, “This has gone far enough!” He said this just as Mrs. Haskins, retrieving his coat from the floor, shook it lightly once or twice and heard the jingle of keys. This was defeat, abject and full.

“Look out in the hall,” Haskins said to his synthetic widow. Gypsy Kitty gaped out, then motioned all was clear. Albert Haskins put the cool hard metal of his .38 against the warm hard head of Detective Gilhouly and escorted him uncompromisingly along the empty corridor, while Mrs. Haskins flipped a key in the lock of a door marked PORTER. Wilbur, about to spring into desperate action, went quietly to slumberland as something crashed against his head.

I am dead, thought Wilbur; dead in the chill grave. He heard somebody groaning next to him. I am here, he corrected himself, in the porter’s room, and in my underwear, but I am not alone. He rose unsteadily and stood in heavy darkness that was not illumined by the flashes that kept going off in his skull. He found a switch and snapped it on. At his feet lay Mutuel Minskoff in his Santa Claus suit, beard and all. Wilbur tried the door, but it would not yield. He looked about for some suitable means to persuade it. He looked, as well, at Santa.

In the street, by now, Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan was confused. Bitterly he reflected you could trust nobody — not even Santa Claus or your esteemed good friend, Gilhouly. That Minskoff, in particular, had shattered solemn trust, the dog, but here Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan paused. It seemed to him that he saw Minskoff now race wildly through the plaza of the Hotel Marshall Arms, arms waving, shouting.

“The hell ya do!” Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan said. He interfered with Santa’s headlong haste. He teed off with his strong right arm and pulled off Old Santa’s beard. Old Santa tripped and looked up from the pavement, short of cheer.

“That’s a nice thing to do,” said Wilbur Gilhouly. “A nice way, Kaplan, I must say, to implement the law.”

The lieutenant postulated. He asked, of all who were there to listen, the one seemingly relevant question: “How crazy can you get?” And, Wilbur, beardless, but in his red-and-ermine suit, seemed a fairly apt reply.

“Albert Haskins is alive,” Wilbur repeated. He had stated this without compromise at least one hundred times. “I seen him. He hit me in back of the head. He locked me in a room. Him an’ his wife. She used to be known as Gypsy Kitty Kl — ”

“My dear Gilhouly,” the lieutenant interrupted, “did you see all these interesting things before or after you got slugged in the head? Did Kaplan see Haskins? … Did you, Kaplan?”

“No, sir,” Kaplan was obliged to say, but he was sorry for Wilbur. “All I seen was this Mutuel Minskoff.”

“And where is Minskoff?”

“Like I said before,” said Wilbur, “he was with me in the porter’s room. I had no clothes on and — All right laugh; laugh, all of you! So I had no clothes on, an’ I had to get out of there. I don’t know what happened to Mutuel after that. I took his suit an’ I — ”

“Gilhouly!” the lieutenant said with sudden fierceness. “How much in cash did Minskoff and Willy Kleebs pay you to concoct this story?”

Wilbur leaped to his feet in anger. His doubled fists and squared jaw made Lieutenant Decker blanch. Inspector Gerhardt, until now quietly sitting by, at this point intervened.

“That will be enough for now, lieutenant,” the inspector said. “I happen to know Gilhouly’s record.” A kindly man, he walked over and examined the back of Wilbur’s head. “A severe blow of this kind can induce all kinds of impressions in a man’s mind,” the inspector said. “Don’t try to think now, Gilhouly. After all, we just now combed the hotel with a flock of cops. We’ve got men in the lobby and at the rear and side exits. The trouble is, Gilhouly, that your story’s not standing up. There’s no sign of Haskins, if he’s alive, and there is no sign of Minskoff. There is nothing in our available files — well, tonight, at least — to support what you say about Mrs. Haskins’ past record. Are you suffering from any personal troubles, Gilhouly?”

“No, sir.” He glanced at the clock. He shrugged. He smiled resignedly. “Three hours to Christmas, an’ I’m supposed to be home by now … You mind if I phone my wife?” he asked. “It’s only a nickel call.

“ … Merry Christmas, darling!” Myrtle said. “Whatever’s been keeping you? … You’re what, dear?”

“All loused up,” said Wilbur. “I thought I oughta tell you I am strictly a crushed cornucopia, baby … Somebody swiped the packages … You what? You ain’t sore? … An’ I can’t get away just now; it seems — ”

“I will be right down,” Mrs. Gilhouly said. “I will be right down in a half hour, Wilbur, to meet you. Don’t you worry … The children? Well, your sister Marge is here.”

Wilbur and Kaplan sat alone in the room. Time passed. There would be further questioning, the inspector had said, when he was able to piece all the claims and counterclaims together, but there did not seem much sense in keeping eight men at the Marshall Arms much longer in pursuit of the unestablished ashes or person of Albert Haskins. Not tonight, of all nights. There was, to be sure, an emergency call from the Hotel Marshall Arms, but it did not concern the detective bureau. The lights of the giant Christmas tree had been shorted; there had been sparks. There was always the hazard of fire.

Wilbur walked to the window and looked up at the star. “Kappy,” he said, “do you believe in miracles?”

“Yes,” said Kaplan; “from now on, anyhow. Turn around, Wilbur. Turn around slowly.”

Wilbur turned. He saw. framed in the wide door of the room, Tax Agent Albert Haskins. Mr. Haskins was in the safekeeping of the emergency squad. Inspector Gerhardt stood with them.

“This,” said the inspector, “is what shorted the circuit on the Christmas tree. It seems he jumped into it from a third-floor window when all those cops were arriving to check on Wilbur’s story. His idea was to cover himself with decorations, then climb down later, I guess, but it got cold up there and he must have been stamping his feet. Anyhow, he blew the lights and put a nice shock into himself. It wasn’t till the lights came on again that the boys could see him hangin’ there like a peppermint stick. We thought maybe you would like to drop him in the lieutenant’s stocking, Gilhouly.”

Wilbur approached Tax Agent Haskins without malice. He touched the lump behind his ear, and then touched Mr. Haskins, to be sure that he was real. He wasn’t even mad at the lieutenant.

“As for small details,” the inspector said a little later, “we can attend to them in due time. We’re picking up Mrs. Haskins and a porter who was in cahoots with them. You were right, Gilhouly, from the beginning, but the way I figure it, tonight a family man’s got things to do.”

It was a clear night. It was cold and framed in beauty. There were lights in the sky and in the Marshall Arms Hotel and in Jablonski’s Junior Joyland. Mr. Jablonski himself stood on the curb with Willy Kleebs.

“Merry Christmas,” said Willy, “to you and yours, Wilbur, from me an’ my ol’ lady … Good evenin’, Mrs. Gilhouly.

Out of the shadows now, wearing a borrowed overcoat above a porter’s uniform that fitted him like a green banana; Mutuel Minskoff emerged.

“I never deserted ya, Wilbur,” Mutuel said. “Willy came back and I told him you were in trouble, an’ when we got here, there’s this Haskins, like a two-legged mistletoe, hangin’ from the tree. We forgot to kiss ’im.”

“Excuse me,” said Mr. Jablonski, “but if you will kindly look in the car, Mr. Gilhouly. A doll’s house, a puppet show, a construction set and electric trains yet. And on the side of the car, Mrs. Gilhouly, tied like a moose, a washing machine … except it is the full-size model, not the portable, mind you.”

Wilbur stammered. Wilbur tried to protest. “Look, boys, it’s sweet, but I can’t be bribed. You must understand it.”

“At Jablonski’s Joyland,” said Mr. Jablonski, “it’s a general clearance, and besides, I just got paid by a certain party. And what is more, Gilhouly, the inspector knows about it. He says you should kindly shaddup your face while Kaplan drives you home.”

The bells in the church were tolling as Kaplan started the car. They tolled the rich, good message of two thousand years, and Wilbur’s heart was full. Mrs. Gilhouly, a bit snug in the front seat with Plain-Clothes Man Kaplan and her husband, reached for Wilbur’s hand. “I wonder where,” she said, “at this hour, dear, we could find you another beard.”

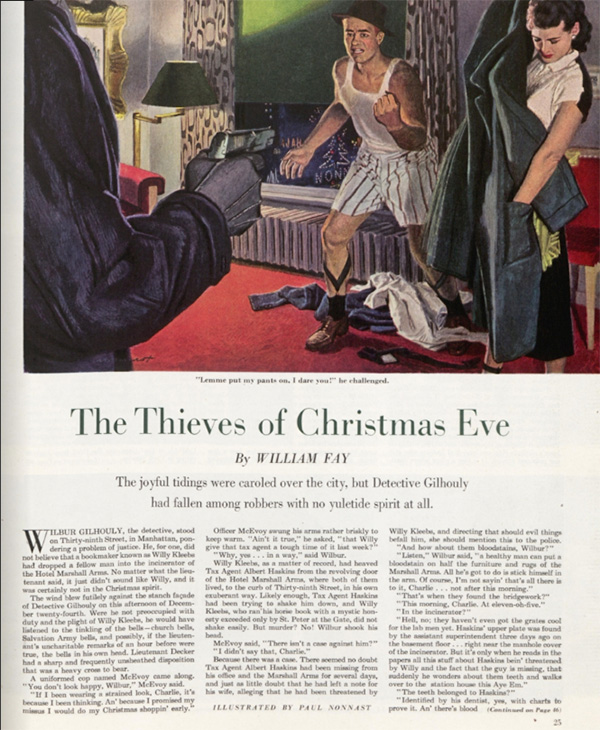

Featured image: Illustration by Paul Nonnast (©SEPS)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now