Gia’s mother had the English written down on an envelope. She whispered the words as they walked, because Gia couldn’t be certain she spelled them all correctly. Her mother wouldn’t pass her second-grade teacher an error-filled note. Mrs. Klein was a dottore, an expert. Their family must present well. Gia was never to show a brutta figura, her ugly side, to the world. This was very important, very Italian.

Gia could remember the smells of lemon and sea from their old apartment in Nervi, the bright colors of the old stone buildings, but she no longer felt the pull of Italian ways, just as she no longer dreamed in her first language. She kept both these truths from her parents. Gia was sure they would find them ugly, even if she did not.

When they reached her classroom, it was the vice principal, Mr. Puhl, who greeted them. “Good morning,” he said to Gia. “You are …”

“Vespucci, Gianna Maria,” her mother answered. She forgot the American order. In Italy your last name, which represented your family, was most important, but here — where every tongue tripped over the syllables — it only meant different.

“Oh, our Eye-talian,” he said. Gia was happy her father was away, cooking at his boss’s new restaurant. He gave pronunciation lessons. Italian was like singing — you had to make the right sounds or it was awful to hear. “Mrs. Klein is sick today. You’ll be in with Miss Cooper this morning.”

Her mother breathed in deep. “About Il Museo Dinosaur,” she began. The practice had worked. She pronounced dinosaur well, cutting hard at the end so the R didn’t get mushed by a vowel.

Mr. Puhl scrunched his face and turned to Gia. This happened every day, with both her parents, and it felt worse than ugly. Her mother had trouble sticking with English only, but museo was so close, and where else would you see a dinosaur, except for Barney on TV? Second graders took the same field trip every year. Gia hated adults sometimes. They made easy things so hard.

Gia checked with her mother. Mrs. Klein waited patiently through her fumbles; Mr. Puhl obviously would not. Her mother looked at the envelope again, her knuckles white, but she tapped Gia’s shoulder, her signal to take over. “My mother has questions about the field trip. She wants to know more about the museum and why we’re coming back at dinnertime.”

Mr. Puhl showed Gia his teeth but continued to look confused. “You don’t have to go.” He glanced at his watch. “You can spend the afternoon in another classroom.”

Gia translated, and her mother squeezed her shoulder. She knew Gia wanted to see the dinosaur bones and the space show, but she didn’t know Manhattan, and she wasn’t sure Gia’s father would approve of the location or the hours. He had a lot of opinions about how Gia and her mother lived, but chefs didn’t like to be bothered at work, and they worked all the time. Gia’s mother had to decide. Sometimes he came home and laughed at her worries. Sometimes he yelled. This was also ugly, but he made beautiful food, which was all anyone cared about. Gia wanted her mother — and herself — to matter more, which meant returning to Italy, which Gia no longer thought of as home, even though it was. Gia was an alien, like her parents, but she didn’t feel like one unless they were around making things feel strange. The envelope bounced in her mother’s shaky hands. Gia sighed. “I can just stay home that day.”

Her mother wiped her palms on her pants, as if her sweat was making them move. “Is maybe, yes?” she said to Mr. Puhl. “But more talk for me.”

“Maybe and yes mean different things,” Mr. Puhl said, and Gia groaned, although she meant to do it only on the inside. Her mother flashed her the quit it now gesture. Rudeness to adults was ugly. Gia knew he started it wouldn’t fly as an excuse. No matter how American Gia became, her mother expected her manners to stay Italian.

“Hello,” Miss Cooper said, squeezing next to Mr. Puhl. “Are you visiting me today?”

“The address of the museo, please?” her mother read out loud. Italian was a fast language, and her mother forgot to be slow with English, which needed more space between the words. She always sped up when nervous. When she returned home, she’d call her sister, Zia Paola, and speak without practice or help from her child.

“For the field trip next week?” Miss Cooper was the new, young teacher and looked directly at Gia’s mother as she spoke. Something Mr. Puhl hadn’t done at all, something a dottore should have known to do. Her mother’s back straightened, and she offered Miss Cooper a small smile.

“I must to say where with mio marito — husband,” her mother corrected, emphasizing the H with her lips, since it was silent in Italian. Miss Cooper’s eyes were a pretty mix of green and brown, and they stayed fixed on Gia’s mother.

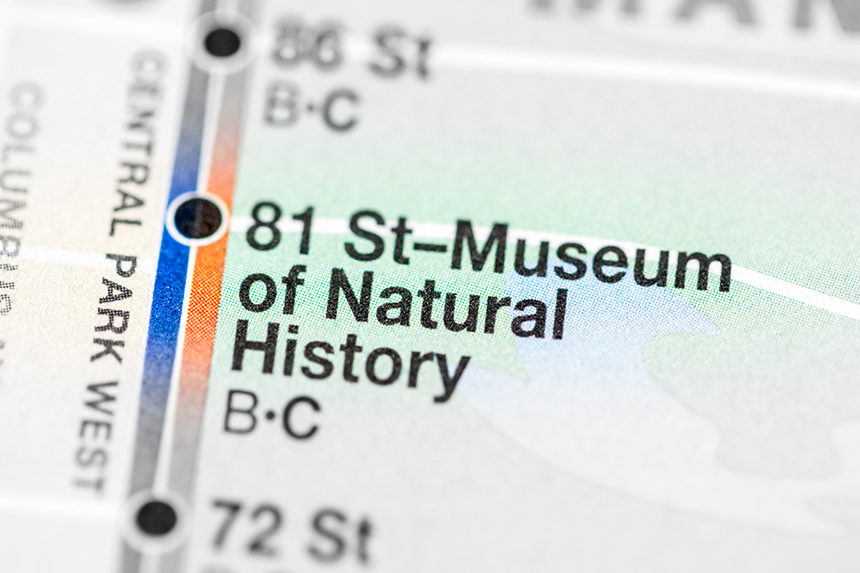

“You two follow me.” Miss Cooper walked them to her classroom, where she had a subway map pinned to the wall. “The Museum of Natural History is at 81st Street and Central Park West, right where the big park is.”

Miss Cooper stepped back so Gia’s mother could take a closer look. She raised the envelope and wiggled her hand. Miss Cooper passed her a pencil, and as she took notes, Miss Cooper asked Gia, “Have you been on the subway?”

Gia nodded.

“Do you know your stop?”

“Halsey Street.”

“So you ride the L train, then.” Gia nodded. Manhattan was the other direction from her father’s cousins in Canarsie, down by the ocean that smelled more like Nervi. Miss Cooper traced Gia’s finger from the museum to where the C train met the L at 14th Street. “Only one change, and you’d be home,” she said.

Her mother’s small smile grew. “Come late?” she said. “How — no.” Her mother took a deep breath. “Why. Home. Late?”

“Traffic,” Miss Cooper said. “The ride back takes time, but we give them a snack on the bus.”

Gia’s mother pulled the permission slip from her purse and signed it. Miss Cooper placed it in the basket on her desk, then she walked to the reading nook and brought back a book, Kids’ Songs Around the World. She flipped through and gestured to Gia’s mother. “Could you help me pronounce the words to this song?”

Her mother laughed and said, “Canti Batta Le Manine.”

Gia sang the “Clap Your Hands” song for Miss Cooper. Her mother relaxed, like she did when she was home, safe in her own language. When Gia finished, she waited. Miss Cooper showed her mother bella figura, the nicest compliment, and Gia would sing or do anything she wanted.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I enjoyed this little American-Italian slice-of-life story, Ms. Fioravanti. Realistically well told in a fun to read style—with dinosaurs!