Good, Christian American families were whipped into a hysteria over a shadowy, secretive — and possibly even satanic — cabal subverting our nation’s democracy, conspiring against justice, and performing bizarre, blasphemous rituals.

This may sound like a modern, paranoid movement on social media, but it’s actually describing a 200-year-old conspiracy theory in the U.S. that alleged that men in the growing Freemasonry fraternity were engaged in a nefarious plot to exert unchecked control over the republic. The Anti-Masonry movement grew to become the first “third party” in the country’s history, permanently altering American politics during a transformative political realignment that would see new parties, ideals, and democratization of the U.S. system.

The spread of Anti-Masonry and its attendant conspiracy theories were aided by the simultaneous religious revivals sweeping across the states, and the movement’s transference into the political sphere met with other opponents of Andrew Jackson. But an important aspect of this conspiracy theory has often been overlooked: it began in reaction to an actual conspiracy.

No other modern historian has spent as much time digging into the history of Anti-Masonry as Kathleen Smith Kutolowski. Born and raised in a small town in Genessee County, New York, she collected otherwise untouched Masonic data from the region, offering a more complete picture of 1820s New York and demystifying the period of supposed hysteria.

Kutolowski’s father belonged to a Masonic lodge. When she began writing her dissertation on the general political development of the area in the 19th century, she says, “I kept running into Masons as political leaders, right down to candidates for county coroner.” She analyzed the records of Genessee and nearby counties and found that Masons were not necessarily the upper-class elites that many had thought; they came from a variety of backgrounds, economic statuses, and denominations.

This was in line with her discovery that there were many more Masonic lodges in Western New York than anyone else had cared to document.“Masonry was a more widespread phenomenon than people understand, and they dominated political office,” she says.

In the 1820s, Freemasonry enjoyed explosive growth in cities, towns, and even small villages in the Northeast. Tens of thousands of Masons had established hundreds of lodges in states like New York, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, and they held “influential civic positions out of proportion to their numbers,” according to Kutolowski’s research. Many of the founding fathers, including George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, had been Masons. In New York especially, Masons held power. But the popular movement against them arose because of the ways they wielded it, particularly in Genessee County in 1826.

That summer, a man named William Morgan announced his plans to publish a sort of Freemasonry tell-all with the Batavia Republican Advocate publisher David Miller. Morgan had attended some local Masonic meetings and claimed to be a longtime member, although the latter was unsubstantiated. His exposé was to be called Illustrations of Masonry, and the Masons at the Batavia lodge became obsessed with stopping him.

They began to harass Morgan and Miller. The sheriff of Genessee County, a Mason, complied with his fraternity and arrested Morgan several times on petty debt charges. Another gang of Masons attempted to ransack and set fire to Miller’s offices. In September, Morgan was sitting in jail in Canandaigua when a stranger bailed him out. Upon release, the writer was ambushed by several Masons and forced into a closed carriage. They drove him to Fort Niagara, and he was never seen again.

Most historical analysis of Anti-Masonry focuses on Morgan’s disappearance as a fairly simple explanation for the birth of the movement, but Kutolowski explored the circumstances around the incident more thoroughly, saying, “The important event was not necessarily the kidnapping itself, but the cover-up that followed.”

Though Morgan’s kidnapping and (likely) murder were an outrage, the Masonic subterfuge that was to come would only exacerbate any extant public perceptions that the fraternity posed a legitimate threat to freedom.

For more than four years, trials and grand jury investigations kept the “Morgan Excitement” in the news and on Americans’ lips. Dozens of Masons were eventually indicted, but not without obstruction from Freemason police officers, politicians, lawyers, doctors, and clergy. Once-Mason and well-regarded New York publisher William Leete Stone thoroughly documented every moment of the Morgan affair at the time in his Letters on Masonry and Anti-Masonry … , maintaining that “the men engaged in this foul conspiracy, thus terminating in a deed of blood, belonged to the society of Freemasons.” Stone tracked the indignant public protest and subsequent legal action over Morgan’s disappearance, but, as he wrote, “they soon found their investigations embarrassed, by Freemasons, in every way that ingenuity could devise.” In the Genessee grand jury trials of 1826-27, five of the six foremen were Masons, including one who was implicated in the scandal. The juries — picked by sheriffs at the time — were full of Masons, or their brothers or sons, and the few Masons who spoke out against the fraternity’s militant protection of its own were expelled from their lodge. Similar circumstances stalled or obstructed justice in Ontario County trials as well.

While the obvious perpetuation of injustice at the hands of Masons generated plenty of reasonable Anti-Masonic sentiment, the more fervent among the movement spun irresistibly fascinating webs of accusations against the fraternity. Kutolowski says that “protest did not leap full-blown from the kidnapping to beliefs about Satanic conspiracies,” but a market for the latter seemed to open up nonetheless.

Morgan’s manuscript was published a few months after his disappearance, and, while it offered an abundance of detail on Masonic practices, the book failed to live up to its sensational promise as “a master key to the secrets of Masonry.” It was soon eclipsed by legions of articles, books, speeches, and entire Anti-Masonic periodicals that disclosed — often fallacious — claims regarding the fraternity’s evils.

In Danville, Vermont, the local paper North Star (not to be confused with Frederick Douglass’s publication of the same name) published a message from the Genessee Baptist Convention in 1828: “That Free Masonry is an evil, we have incontrovertible proof; and this appears from its ceremonies, its principles, and its obligations.” A few months later, the Star reprinted (from Morristown, New Jersey’s Palladium of Liberty) one Mason’s “renunciation” from Freemasonry, colorfully painting the fraternity’s membership as men “whose hands reek with the blood of human victims offered in sacrifice to devils, or who worships a Crocodile, a Cat or an Ox.” Such dramatic renunciations by supposed ex-Masons were regular fixtures in Anti-Masonic papers, and lists bearing the names and towns of recent Masonic renouncers often accompanied them.

An 1831 issue of Vermont’s Middlebury Free Press featured a fictionalized dialogue between the mythic demons Belphagor and Beelzebub in which they boast of their Satanic sway over Freemasonry (“That bulwark of our empire on earth!”) and delight in their ungodly machinations against the republic (“ — that post, well-fortified, in our enemy’s country, from whence, at pleasure, we may make successful inroads upon his friends and people!”) .

Anti-Masonic fervor wasn’t contained to printed communications; it manifested in real-world violence as well. Though Freemasons had traditionally marched in annual St. John’s Day parades, their celebration in Genessee County in 1829 was met with Anti-Masons who threw rocks at them. Then, protesters ransacked a Royal Arch Chapter headquarters. Freemasons were spooked — particularly those in Genessee County, where 16 of the 17 lodges and two chapters soon dissolved. But for many Anti-Masons, public renunciations and even dissolution of local Masonic charters was not enough. They held that Freemasonry must be abolished, that its mere existence — even if it was weakened and relegated to the shadows — was proof that their work was yet unfinished. Wilkes-Barre’s Anti-Masonic Advocate expressed as much in 1832: “To overcome this evil is a work of intelligence, and a work of time. We have scotched the snake, not killed it. We have forced it to hide in darkness — but though unseen, it is not less dangerous.”

Anti-Masonry’s entrance into electoral politics was swift: the spring after Morgan’s kidnapping saw Anti-Masonic candidates for office in Genessee County. “Their level of organization was amazing,” Kutolowski says, “right down to school district committees, taking a social issue to the ballot box.” Since Anti-Masons viewed the fraternity as an existential threat to the budding country’s republican values, they turned to grassroots democratic mobilization to uproot it.

The Anti-Masonic Party grew into a national force vying for power up and down the ballot in the 1830s. It was the first such third party in the country, dwarfed by the National Republican Party (later the Whigs) and the Democratic Party. The Anti-Masonic Party held the first presidential nomination convention of any political party in U.S. history in Baltimore in 1831, choosing former U.S. Attorney General William Wirt for their ticket. Wirt garnered more than 100,000 votes (almost eight percent of the popular vote) and won the sole state of Vermont in the 1832 election. The party also elected Vermont’s governor along with plenty of local and state seats, but it fizzled out over the course of the decade.

The question of the Anti-Masonic Party’s legacy is anything but settled among political historians. Was it all a righteous democratic force for justice or a cynical conspiracy cult? Many have cast the Anti-Masonry movement as a right-wing reactionary one, citing the economic angst and ardent religious character of its adherents. Although “its witch hunting disrupted churches, families, and communities,” Anti-Masonry had a negligible effect on American politics, according to Donald J. Ratcliffe.

But two-time Pulitzer-winner Richard Hofstadter, writing on the “paranoid style” of American politics in Harper’s in 1963, allowed that Anti-Masonry “was intimately linked with popular democracy and rural egalitarianism.” Other histories have also credited the Anti-Masons for enshrining democratic processes as a populist force for “equal rights, equal laws, and equal privileges.” Author and historian Ron Formisiano examines the populist aspects of Anti-Masonry in his book For the People … . He says that Anti-Masonry has received similar unfair treatment as other American third parties in the 19th century, reduced to “movements of bigotry” without consideration for the complexity therein. He claims the Know Nothing Party is similarly derided and misunderstood in modern times in spite of its connection with important, democratizing reforms.

The kneejerk labeling of Anti-Masons as religious zealots and reactionaries has met resistance as historians like Kutolowski have more closely examined the circumstances around the movement.

Kutolowski says the Anti-Masonry movement had “an enormous role in the development of American political culture.” In addition to pioneering democratic political party operations like the national nominating convention, Kutolowski points to the party’s championing of reforms like making kidnapping a felony and ending the appointment of jurors by sheriffs, as well as their backing of economic goals that would become mainstream, like antitrust laws. After its dissolution, much of the movement’s supporters would turn to the cause of anti-slavery.

With regard to the Anti-Masons’ primary goal — the complete abolition of the fraternity — they were, of course, unsuccessful. Though the reputation of Freemasonry was tarnished for decades, Mason lodges still operate in the U.S. and around the world. Masonic history of the Anti-Masons has often cast the phenomenon as a paranoid, discriminatory crusade. Even in recent years, members of the “ancient and honourable order” have occasionally decried public “misconceptions” about their organization, namely regarding the inconsistent inclusion of women among lodges.

The popular movement against Masons is long over, but in the age of social media — one in which virtually any conspiracy theory can take root — anti-Mason rhetoric is still out there. The charges leveled against Masons indiscriminately by internet users are much more complicated than those out of Western New York a few centuries ago. Conspiracy theorists on social media have woven anti-Masonic theories into the lore of “QAnon,” along with many other theories regarding a cabal of satanic, cannibalistic pedophiles and the Trump administration’s heroic crusade against them. Such posts might call attention to Masonic-seeming symbols in photographs of the British royal family or in the logos of Gmail or government seals. The implication is that Freemasons (along with Illuminati, Hollywood, Democrats, and Jews) exert far-reaching influence in government and culture and hint at their schemes with cryptic numerology. Recent studies have documented enormous spikes this year in social media users spreading the baseless QAnon theory, leading to several platforms taking steps to remove such content.

Kutolowski has not followed much recent news about QAnon or current conspiracy theories around Freemasonry, but she says they could be with us for a long time. She is adamant that the Anti-Masons of the 1820s and ’30s — unlike Pizzagaters and QAnons — have been branded unfairly as wacky conspiracy theorists by historians and journalists. She recalls the words of an Anti-Masonic town leader, defending the veracity of their cause: “All the evidence of historic demonstration will be necessary to convince those that come after us that the record is true.” But, as Kutolowski’s work might demonstrate, the existence of such evidence is not necessarily enough; someone must be willing to seek it out.

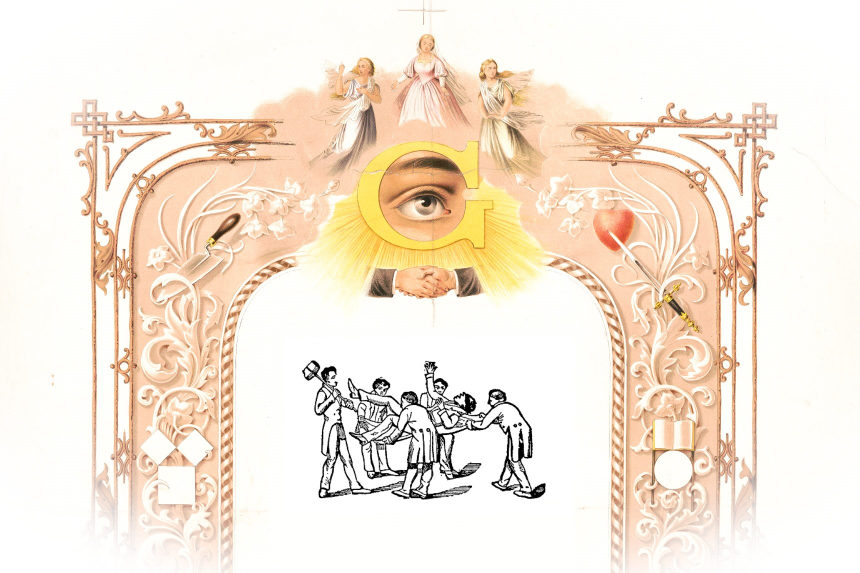

Featured image: “The Lord’s Prayer of the Freemasons,” Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, 1870 and Illustrations of Masonry, Utah Lighthouse Ministry, 1827

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now