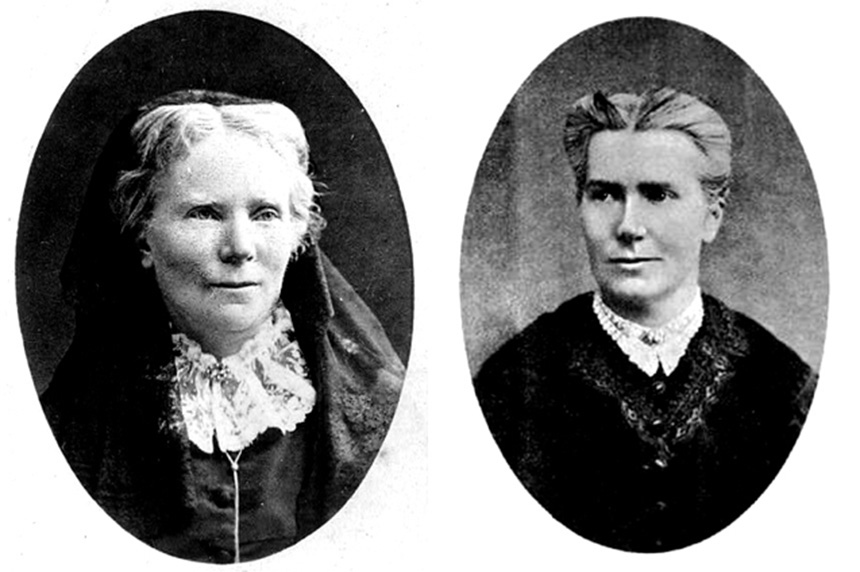

Elizabeth Blackwell, the country’s first female doctor, was born 200 years ago today. The contradictions and curiosities of Blackwell’s life — as well as those of her sister, Emily — have been captured in the recent book The Doctors Blackwell by Janice P. Nimura.

The Saturday Evening Post: What do people often misunderstand about “first women” in historically male-dominated fields like medicine? How does Elizabath Blackwell fit into or clash with modern conceptions of feminism?

Janice P. Nimura: We tend to want our heroines to be a combination of saint and Amazon: graceful warriors whose iconic achievements instantly change the world. Elizabeth Blackwell — like all “first women,” when you look closely — is a more complicated figure. She was out of step with the emerging women’s rights movement, and often disdainful of other women. She strove to be an example to women everywhere, but she wasn’t necessarily interested in collaborating with them. And once she had achieved her goal, she continued to struggle in many ways.

SEP: What should we know about the practice of medicine in the mid-19th century, before even the acceptance of the germ theory? It was quite different than how we understand medicinal research and care nowadays, right?

Nimura: Blackwell received her degree in 1849, at a moment when medicine was entering a period of rapid change. To this point, medical care looked much as it had since antiquity: a matter of guesswork and better-out-than-in, treating illness with a range of uncomfortable and often downright dangerous remedies including bleeding, blistering, emetics, enemas, and mercury- and opium-based drugs. Alternative therapies, including hydrotherapy, magnetism, and homeopathy, were coming into vogue in reaction. The prevailing wisdom assumed that illness was often a result of immoral behavior or lack of emotional strength. Doctors tried all the tools in their cabinets one after another, often indiscriminately, until the patient recovered or died. And none of them washed their hands.

SEP: Are there any specific challenges, in your experience, to writing history about women? Digging through archives, letters, papers, how do you approach this history to account for prejudice in the record (any particular examples of this?) and tell the most complete, accurate story about female figures?

Nimura: It’s true, women’s lives are usually harder to trace through the archival record — their personal papers were preserved less often, and the public commentators of the 19th century were mostly men. In the case of the Blackwells, though, there is a wealth of material — it’s one of the things that attracted me to the project. The five Blackwell sisters were educated to the same high level as their four brothers, and as the nine of them were rarely all in the same place at the same time, they were constantly writing to each other, as well as keeping their own journals. It gave me an extraordinary opportunity to listen to multiple voices responding to and commenting on each other’s lives.

SEP: You’ve dug deep into Elizabeth Blackwell’s record and papers to give a detailed, colorful depiction of a provocative — at times, contradictory — character. What was her motivation for striving for such a historic accomplishment?

Nimura: Blackwell was voraciously brilliant and had a healthy ego — even as a teenager, she saw herself as someone who could make a mark. She became captivated by the Transcendentalist writer Margaret Fuller’s idea that humanity would not achieve a higher level of enlightenment until women proved their own strength and claimed their independence. Fuller argued that women could be anything they wanted to be — it was simply a matter of talent and toil, not sex — and Blackwell saw herself as someone who could prove Fuller’s point. She chose medicine not because she was drawn to science or healing, but because it was a clear and strategic way to go about this. If she attended all the lectures and passed all the examinations at medical school, who could argue she wasn’t qualified to be a doctor?

SEP: How did Elizabeth’s male peers at Geneva Medical College react when they were joined by a “lady doctor” for the first time in history?

Nimura: Geneva’s students had heard from their professors that a lady wanted to join their class, but they thought it was a joke — possibly a prank cooked up by a rival medical school. When she walked into the lecture hall for the first time they were stunned — one student remarked later that a lecture had never been attended to in such perfect silence. During the early weeks her new classmates whispered and mocked, but Blackwell’s determination and discipline soon put her at the head of the class, and she became a respected elder-sister figure. Geneva College was proud to celebrate her achievement when she graduated, but they thought of her more like a comet: a streak of awe-inspiring light that leaves the stars unchanged. After she left, they barred the door against other female students, including Elizabeth’s sister Emily.

SEP: Elizabeth seems to be the star of the story, but you also spend quite a bit of time telling her sister Emily’s story. She really continued Elizabeth’s work and gave it longevity, right? How was her approach to medicine and running their hospital and school different from Elizabeth’s?

Nimura: It was important to me to tell this as a story of two sisters, not just the First Woman Doctor. Recognizing that the path she had chosen was a lonely and arduous one, Elizabeth anointed Emily, five years younger, to follow her into medicine. Emily was passionately interested in natural science, and though she, too, was low on empathy for her patients, she became a more dedicated and accomplished physician and surgeon than Elizabeth, who eventually veered more toward public health. Once the sisters had founded the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children and its Women’s Medical College, Elizabeth returned to her native England for the last four decades of her life, leaving Emily in New York to lead their institutions. Elizabeth was more comfortable as an idealist and an activist, always on to the next quest, whereas Emily was better at leading a team and dealing with more quotidian challenges. She sustained her sister’s legacy in America to the detriment of her own — today, even those who are familiar with Elizabeth’s name are often unaware of Emily. I wanted this biography to remedy that.

SEP: Elizabeth’s moralistic attitudes toward sickness, prostitution, and sexual intercourse are a far cry from how we understand modern feminism, and they even differed greatly from women in the suffragette movement that came toward the end of her life. How can understanding these historical differences help us to better understand where we are now in terms of gender parity?

Nimura: Elizabeth liked to say she was too progressive for the conservatives, too conservative for the progressives. She thought suffrage was the wrong priority for the women’s rights movement: why give women the vote when they were all too likely to vote as their fathers and husbands told them to? It was more important, she thought, to focus on lifting women out of their dependent status first. Her ideas about moral behavior, from sexual purity to family planning, existed at a level of idealism that was out of step with everyday life. For me, the Blackwell story is a lesson in how we see our heroines. Elizabeth and Emily were judgmental, unbending, occasionally misogynist — and at the same time their extraordinary determination did change the world. They have helped me understand the importance of holding contradictions in our minds, of admiring trailblazers even while acknowledging their flaws.

Featured image: Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell (Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thanks for this insightful article on not only the fact these sisters opened the way for women in medicine, but also for their contributions to medicine otherwise. The feature also shows how things really began accelerating starting in the mid 19th century in general, and particularly after the Civil War in all manners of life with the Industrial Revolution looming not long after.

It also shows that not all women were on the same page with each other. We always hear about men vs. women, or men suppressing women which is true enough. But we know men have suppressed men as well historically. It would be a mistake to think women didn’t do this to other women as well. Hopefully today as things become more gender-neutral, such actions on the part of both sexes will lessen.