Any university worth the price of its exorbitant tuition had a COAC scholar, usually several. The number of scholars was an indication of a university’s priorities. Ostensibly, the COAC scholars were also there to teach classes, but they were more than just graduate students. They made livable wages while their regular counterparts struggled. COAC scholars didn’t have any work outside of the one class they taught and the COAC work they were there to do. The universities understood the COAC process was long and grueling and often fruitless, which was why the universities had endowed seats for scholars to do the work. A COAC scholar could be in residence for five, ten years before an application was ever accepted. But once an application was accepted, there would be nothing in the way of the COAC scholar striding down the streets, heart pumping, stomach bubbling, to the COAC building to finally be a COAC candidate.

And for Barbara, that day was today. She had to keep her hands from fidgeting as she sat in the white hallways of the COAC building’s fourth floor, waiting to be called by her COAC manager. The floor was mainly cubicles, white dividers cutting up the room. There were several doors all along the walls, leading to private offices or private rooms, Barbara couldn’t tell. Sitting near one door, Barbara saw no sign indicating what lay behind it. Looking to the far end of the room, she spotted one set of double doors, shut tight. She wondered if she would find out what lay beyond any of these doors.

She tried to settle her nerves. She was here to do a job and she would be a professional. But it was hard to contain her excitement. After months and months of rejections from COAC, she’d practically flown down the university’s hallways, dodging undergraduate students, graduate students, professors, and COAC scholars alike, to get to her mentor’s office to show him her acceptance from COAC. She was now officially a COAC candidate, no longer an applicant, and she didn’t think her heart could handle it. The rest of her body was certainly not cooperating, sweating and trembling in its turn.

She could still feel the sting of the too-numerous-to-count rejections she’d received. She’d asked her mentor to review her applications before she submitted them and he’d always been honest with her, brutally so sometimes. He told her the truth about her applications, that most of them would not be accepted by COAC.

“But the Greats did it like that,” she fired back on more than one occasion.

He shrugged each time. “The Greats belonged to a different generation, different rules. You have to play by the rules now if you want to play this game.”

Initially, she’d ignored his advice and submitted the applications anyway. Each was rejected. After a while, though, she started heeding his advice. She could handle the criticism from her mentor a bit more easily than the form letters from COAC. COAC didn’t even bother putting in people’s names in the rejection forms, they sent them out so frequently.

She wished she’d brought a book to read while she waited, even though her mentor had advised her not to. He’d also advised her not to take out her phone too much, not at all if possible. As the minutes ticked by, she was sorely tempted to, but she knew her mentor would not steer her wrong when it came to matters like these. She leaned back against the chair, her head resting against the well, trying to get comfortable in the hard seat.

She also wished there were windows, but she couldn’t see any from her seat. The sun had been out on her way over, the breeze blowing with the promise of spring. After her first day at the university, she’d gone to find the COAC building, staring at its brick walls in hunger. One day, she promised herself, one day I will walk through those doors. She had not been back since, letting that one moment spur her onward while she wrote application after application, received rejection after rejection. She had begun to worry that her university funding would run out before she got an accepted application, or that the university would simply take her scholar position away from her after so many rejections.

“They won’t do that,” her mentor assured her. “Very few people are getting applications through COAC. The university knows it needs to be patient with its scholars if they ever want us to produce anything. They have a vested interest in ensuring you and I and all the rest of us succeed.”

It was four years, seven months, and five days since she had last stood in front of the COAC building, but her feet knew the way, a magnet being pulled through the streets. She hadn’t needed to think about her route, as she restrained herself from running all the way there, skipping and then slowing down to take her time to simply enjoy the weather and the wonder of the day until she came to stand in front of the brick building once again and finally pass through its double doors.

Barbara sighed and thought about Jenny, hoping it would keep her mind off things. Jenny had been telling Barbara about an issue she’d been having at school with one of her friends. Jenny had been distraught over it, but hadn’t elaborated on the problem. Barbara was wondering what the issue might be when the conversation from one of the cubicles grew loud enough to draw her from her thoughts and eavesdrop without effort.

“…a mistake. We apologize for the inconvenience, but we cannot allow this application to go through.” Barbara couldn’t see the body attached to the voice, but she suspected it to be a stern woman in her mid-forties with a take-no-prisoners attitude. This must be one of the managers. She felt for the COAC applicant being spoken to. She would hate to have come all this way only to have her application rejected here. She hoped that would not be her fate.

“But—” the applicant responded, a male voice, panicked.

“There are no exceptions,” the female voice responded. “When you neglected to fill out your title and gender identity on the application form, we thought this was due to your personal right of privacy. Had we known your gender identity, your application would not have gotten this far in the process. I apologize again for the inconvenience.”

“But I—”

“Sir, your main character is female. You are male. Nothing in your personal file suggests you have ever been female. You cannot possibly tell the story of a female. Your application is denied. I apologize again for the inconvenience. I must ask you to leave now. There are other applicants waiting.”

Barbara bit her lip, waiting to hear more. There was a shuffle of papers, the scuffling of feet, and she leaned back in her seat, trying to blend in with the wall, when the man — a tall man, shamefaced and folding in on himself — rounded out of the nearest cubicle and rushed toward the elevators. She didn’t recognize him, so he was probably a struggling artist with a day job of some sort. She knew all the scholars in the universities in the area, and he wasn’t one of them. The scholars traded war stories when they got together over drinks twice a month to commiserate together over the COAC process. She couldn’t imagine the pain and humiliation of having to make that reverse trip, down the elevators, past the floors of all the COAC artists, across the lobby, through the front doors, under the sprawling words — CENTER OF ARTS CREATION — and into the glorious mocking sunshine.

Barbara looked after him and shook her head when the elevator doors clicked shut. It was a rookie mistake, one she’d made on her first application.

She’d completed her first COAC application while waiting tables at a local diner and applying for COAC scholar positions. She wanted to be a COAC artist, but with the COAC process so difficult and often fruitless, it was hard to work a full-time job and also produce viable applications. There was no money in rejected applications. Scholar seats were the best way to go from being a nothing to a COAC candidate and maybe eventually to an actual COAC artist. She could remember weeks of coming home too tired from the diner to do much of anything, her bookshelf of Greats taunting her in the corner. Becoming of a COAC scholar at the university had made COAC applications a possibility again.

She’d received her very first COAC rejection letter the same day she was accepted for an endowed COAC scholar seat. It had taken some of the sting out of her COAC rejection, knowing the university thought her worthy of investment.

Her second day at the university, the sight of the COAC building still fresh in her mind, she’d shown her mentor the rejected application, hoping he would shed some light as to why. The rejections never explained why the application had been rejected, only that it had, thank you for your efforts, please try again.

“Well, your character is a boy. You aren’t.”

She’d felt stupid for asking such an obvious question in the first place. Of course, she couldn’t possibly know what it was like to be a boy, having never been one. It was no wonder the application hadn’t been accepted. She’d been sad, but it had been easy to understand the rejection and let it go then.

She’d struggled more with letting the fantasy fairytale application go, but her mentor had explained just as simply, “Your character can do magic. You cannot.” She’d heard one of the graduate students who studied fantasy literature complain frequently, and loudly, about the last time a fantasy book, or any other fantasy-related art, had been made, decades ago. Now she knew why.

The woman came out from the same cubicle as the exiting applicant and said her name. Barbara looked and saw that this woman was younger than she had expected, closer to her own age. She stood up and shook her hand and joined her in her white cubicle.

The woman introduced herself and said, “I will be your COAC manager for this application. We have reviewed it and everything appears to be in order. The next part of the process will be providing samples for your COAC file. Our system is set up so that once these samples are collected, you should not have to provide additional samples with any subsequent COAC applications. We are all very pleased about that, since it will streamline the process.”

Barbara nodded and smiled. Her mentor had told her a little about the sample process, but she didn’t really know much about it. He’d simply told her it existed. All the other scholars who’d gotten applications successfully accepted and through COAC had been similarly vague. She had not appreciated the mystery, but she’d satisfied herself with the belief she would find out on her own soon enough. Here she was. She did like the thought of only having to do the sampling once. She liked the thought of having subsequent COAC applications accepted even more.

The manager printed out some documents, the white paper pushed out of the white printer. A light flashed green for a moment before it set the machine whirring. The manager took the hot papers and a pen and presented them to Barbara.

“Please sign these forms, consenting to the taking and keeping of these samples. They will not be shared with the public unless your credibility comes into question. At that point, it is up to the discretion of COAC which samples, if any, to disclose. By signing these documents, you also agree to a non-disclosure agreement surrounding your activities going forward here at COAC.”

Barbara nodded and began reading the form. She wanted to go straight to the last of the pages and sign on the dotted line, but she knew that was not the professional thing to do, and she was going to be a professional even if it hurt. She wondered at the non-disclosure agreement, though now she understood why her mentor and the other scholars had always been so vague about what happened at COAC.

The first pages reiterated what the manager had just said in convoluted legal language. The next pages listed the samples that were going to be given — hair, blood, skin, height measurements, weight measurements, saliva, urine, eye exams, flexibility measurements, muscle measurements. She swallowed sharply. She was the person who cringed every time she had to visit the doctor to get shots or have blood taken. This was not the sampling she had expected.

“Our technology has advanced quite quickly. I will receive your sample results moments after they have been taken,” the manager said as she watched Barbara continue to read down the list. “I will be reviewing your application against the sample results as they come in, a final check before proceeding to the—”

“Excuse me,” Barbara interrupted, looking up from the list, “how exactly will the genitalia, gender, and sexuality samples be given?”

She nodded. “Yes, we often have questions about those. The genitalia sample will simply be an image of your genitalia to prove your biological gender. The gender and sexuality samples will be a brain scans while you watch various images. Your brain scan will give an indication of how you identify in terms of gender and what you are sexually attracted to.”

Blood and skin and weight was one thing, but this felt a bit much. Her application had not even been about sexuality in the first place.

“These tests are absolutely necessary to ensure that no story is misappropriated,” the manager said, noting Barbara’s hesitation. “You will not be able to proceed should you choose not to provide the samples. I assure you, no one beyond COAC will ever see them unless there is a question of credibility, but since the creation of COAC, those anomalies have been rare.”

This did little to reassure Barbara, but she wasn’t about to give up her chance because she was squeamish. Her mentor was a COAC artist, like all the other scholars at the university who had successfully gone through the COAC process, and he must have given these same samples. She understood now why the agreement was made secret. She wanted to be a COAC artist, but she might have rethought her desires had she been forced to think of these samples in the abstract. Now that she was here, her application mere tests away from full acceptance, her answer was clear.

She reached the last page and signed on the dotted line, printing her name and the date right below. She pushed the papers away from her, the red ink garish in the white surroundings.

“Good. Follow me, please.” She stood and led Barbara out of her cubicle and down the hallway to one of the unmarked doors. She opened it and gestured for Barbara to walk through. “One of our examiners will be with you shortly.”

Barbara couldn’t see much beyond the door, just a table like in a doctor’s office, white and sterile. Her stomach squirmed. For a moment, she considered walking away, going back to the elevator, down the four floors, out the building, and walking home. Would she look back, see CREATION OF ARTS CENTER emblazoned on the brick? If she did, she knew it would be for the last time. She would never have to wonder again about another application acceptance. There would be no point in any more applications, not if she could not get through this one.

But she wanted to share her story with the world. It was an idea that was dear to her. She couldn’t just give up on her characters and their story so easily, not if she ever wanted to share it with someone beyond herself.

“They need us,” she heard her mentor’s voice reassuring her in her head. “The university, its students, and every other person who loves art needs COAC artists. Without us, there would be no new art left to share.”

Barbara walked into the examination room. The manager let the door close and Barbara was alone, hearing the lock click shut behind her.

She’d picked out her outfit carefully that morning, sifting through hangers of clothes in her dark closet. She’d wanted to be comfortable, but serious, something that said she was artsy but that she also meant business. Her work was her passion. She intended to make a career in being a COAC artist, novels on bookshelves, sold around the country and the world. What she’d worn to her first COAC acceptance had felt like such an important statement of the kind of scholar she was and kind of artist she would be; she had agonized over it the night before, trying on five different outfits, posing in her bathroom mirror. She had not expected having to take her clothes off until she’d returned home, exhausted but vindicated. Now, sitting across from her manager’s desk again, she could feel her clothing against her skin, but she wondered if it was really there. She could still see the flashing lights as the examiner took picture after picture of her body — every part of her body. Her arm was sore from where the examiner had taken skin and blood. She didn’t want to think about any of the other samples she’d had to give. She didn’t close her eyes. She didn’t want to even blink.

Her manager had offered that they resume after she eat something at the cafeteria on the second floor, but Barbara had refused. She was here to be a writer, a COAC artist. That was what she wanted to do now. And besides, she was not hungry.

Sitting back at the cubicle, her manager was typing something into her computer; Barbara wondered if it had to do with her application or her results. She figured she would find out soon enough. She heard someone coming up the hallway and glanced out of the cubicle and saw the far-off double doors close shut and a stone faced man walked quickly past the desk. His hands were stuffed in his pockets, clenched, making his dark jeans bulge at the hips. She watched him as he walked to the elevator and pressed the button with his elbow.

“All your sample results look good,” her manager told her with a small smile. Barbara looked back at her. “No major discrepancies. Your main character appears to be agnostic, which is an allowed option even though your file has you listed as Christian.”

Her mentor had warned her on a previous application to stay clear of religion. It was simply too divisive a topic, even by the artists who wrote about their own religions. All it took was one COAC official to read it and have a different religious experience to shut down the application before it got close to printing.

“There are a couple of details in your application though that will need to be fixed,” her manager said, reviewing the sheaf of papers in her hands.

Barbara was confused. Her application was about a young girl growing up in a small town. There were some scenes that did not exactly mimic her own life, but she hadn’t thought that those things would be a problem for COAC.

“Your main character has been described as a blonde. There are no records of you ever being a blonde. You will have to make your character a brunette.”

Barbara stared at her. Did her character’s hair color really matter that much? Her mentor had led her to believe COAC was more interested in the overall truth of any application and the subsequent art, not the details as minute as hair color.

“There’s also a matter of the pet. Your main character is said to have a cat. There are no records of you ever owning a cat.”

“My roommate out of college did,” Barbara said. The fluffy orange tabby had loved to knock her books off her desk when Barbara’s roommate didn’t feed him on time or had locked him out of her own bedroom. Barbara had never gotten around to putting a lock on her door, so the cat had bothered her instead. She hadn’t minded too much most days. She’d liked the cat. She’d liked that her roommate had named the cat after the pet of a Great’s character that both of them had grown up reading and loving.

Her manager shook her head. “That will not do. You were not the cat’s owner. Our records show that your family once owned a dog. You can either have your character own a dog or no pet at all. You will need to consent to these changes before we can proceed.” She looked up at Barbara, a red pen poised over her application papers, her accepted COAC story. Barbara could make out the upside-down title and her scene-by-scene plot outline.

It didn’t really matter to the story that Jenny be blonde or own a cat, not in the scheme of her whole story. Except that Jenny was blonde and was a cat person. She wouldn’t be a brunette or own a dog, not in real life. Barbara could see her Jenny so clearly in her mind, heard her voice for months as she’d plotted and prepared Jenny’s story for application. She’d listened to Jenny’s woes at school, her joys with her friends, her anxiety about growing up in a large family. Barbara would know Jenny if she saw her walking down the street. It didn’t matter she existed solely in her mind, a figment of her imagination. Jenny was real. And she was a blonde. And she owned a cat. Could she really betray Jenny like this and deny who she was?

Her manager’s pen hovered over the pages. If Barbara refused the changes, her application would be denied. Everything would have been for nothing.

“I accept these changes.”

Her manager signed the pages. Barbara found it hard to breathe.

“Good. You are now a COAC candidate. Now if you will please follow me, I will show you to the Writing Room.”

Barbara smiled weakly and followed her. They walked past the doors of the examination rooms. She refused to look at those doors, staring resolutely at the back of her manager’s head. They came to the double doors at the far end of the room. Her manager opened one for Barbara and followed her through.

This room was also pure white, with a row of lockers, several white boxes of tissues, and another set of double doors beyond.

“You will have to leave all your belongings in one of these lockers. You may only take your locker key and your application papers into the Writing Room. Should you not finish writing your work today, you may schedule further times to come back to the Writing Room. Once you have finished work, it will be reviewed by a Post Completion committee. Assuming it passes that review, your work will proceed to publication.” Her manager offered the application papers to Barbara, who took them carefully. “If you have any questions, feel free to come back out and find me. It has been a pleasure working with you.” Her hand was offered and Barbara took it, shaking it lightly. With a small smile, her manager turned on her heel and exited the room.

There were several open lockers. She picked the closest one, stuffed in her bag, and locked it. She wished she could bring her phone with her, but she didn’t want to risk any trouble, at least not today. She knew she would be back several times. Her application was for a novel. Even on the best of days, there was no way she would be able to write more than a couple of pages. This was what the university helped with, providing financial stability while she wrote her novel, now that she was a COAC candidate, applicant no longer. The title change thrilled her. Maybe another day she would try to sneak her phone into the Writing Room.

She crossed to the opposite double doors and pushed them open. She blinked, the yellow light shocking after the bright white of every other room. The room, once her eyes had adjusted, gave the impression of an old-fashioned library, cozy and welcoming. The wooden desks were worn and old, the chairs comfortable looking. She expected to see books lining the walls, except there weren’t any. There were no windows. She wondered if the mellow lighting was intended to offset the lack of sunlight.

There was only one other person in the room, a woman, hunched over a typewriter. She didn’t even look up when Barbara walked through the door; she just continued typing, the click-clack of keys filling the room. While Barbara stood there, the typewriter dinged and the woman pushed the carriage back to the beginning of the page. She wondered why the woman was using such an out-of-date machine to write on, until she looked at the other desks. All of them were equipped with a typewriter. There were no computers in sight. Looking around the room more carefully, Barbara noted that the only modern technology in the room were the lights in their bulbs in the ceiling.

The woman’s machine dinged again. She was typing at a furious pace. Barbara smiled. This was why she was here, in this room, breathing the same air as this writer. She was here to tell a story, and that’s what she would do.

She sat down at the desk across the aisle from the woman, sinking into the chair. It felt so comfortable after the unyielding seats outside. She figured many a tired writer had napped in these chairs before, but she shook herself, sat up straight, and leaned over the typewriter. She’d never seen one up close in real life before, but she’d seen plenty of old movies that had old writers typing on machines like this.

There was also an instruction sheet placed beside each typewriter, explaining how to properly set the machine. She fed the paper into the machine and stared at it. She could never decide whether she loved or hated the blank page. She knew some writers dreaded it, her mentor being one of them, but she couldn’t bring herself to fully hate it. A blank page meant possibilities, a freedom to go wherever the words took her. All she had to do was start.

She placed her hands on the keys and began typing, her click-clacking joining that of the other woman’s. She thought of Jenny, her now brunette protagonist, and soon her typewriter dinged. She’d finished her first line. She pushed her carriage back to start the next one.

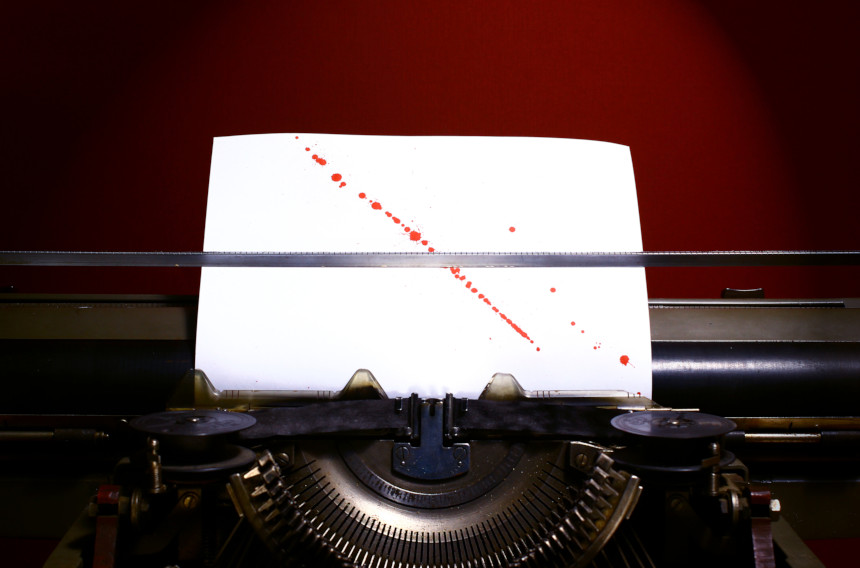

She was almost done with her first paragraph when she noticed her fingers tingling. This was normal for her, as her excitement for the story pulsed through her. She ignored it. She was nearing the end of the page when the tingling turned to pain. She lifted her fingers and saw small droplets of blood oozing over her fingertips, every single one of them. She swallowed. When had she cut herself? How had she cut herself on every single finger? She peered at her fingers closely. The cuts didn’t seem deep, just pin pricks, as if she’d stabbed herself with a needle over and over again. Her grandmother had taught her how to use the family sewing machine when she was younger and she’d stopped after she’d pricked a finger one too many times. But there were no needles here.

She looked down at the typewriter and saw how her blood had stained the white letters a rusty red. But because they were stained, she was able to make out the sharp points on each of the keys.

None of the movies ever showed needles in the keys of typewriters.

Shaking a little, she stood up, trying not to touch anything. She didn’t want to get her blood on any of the papers or the desk or the chair. She needed to go wash her hands, and then, when she came back, she would switch typewriters. The cuts weren’t deep enough to be bandaged just yet. She could feel the blood drying on her fingertips. She maneuvered out of her seat, pushing the chair back with her legs, and headed for the doors.

“They’re meant to do that.”

Barbara stopped and looked at the woman. She continued typing, click clack, and then her typewriter dinged and she looked up.

“Excuse me?”

She jerked her chin toward Barbara’s bleeding hands. “They’re meant to do that.” She lifted her hands.

The woman’s fingers were covered with blood.

Barbara’s hands dropped to her sides. She glanced at all of the typewriters. Were they all like this?

“Each and every one,” the woman said, noting Barbara’s gaze before moving the carriage over to start a new line. “They’re designed like that. It’s best to just work through it. You get used to the pain.” Her click-clacking resumed.

Barbara leaned back against the table, her legs feeling shaky beneath her. “But … why?” She couldn’t understand what the purpose of bleeding while typing was.

The woman stopped typing and looked over at Barbara, her eyes harsh. “Take a look at your page.”

She didn’t want to. There was something menacing in the woman’s tone. But she turned around and looked at the page. She saw her words, typed out, dark against the white page, the beginning of Jenny’s story. But now that she was really looking, there was something strange about the letters. The ink wasn’t fully dry and it wasn’t fully black. She took the page out of the machine, leaving bloody fingerprints on the margins. She held the sheet up toward the light. She turned back around to look at the woman who was watching her closely.

She nodded. “Every word.”

Barbara dropped the paper like it was on fire. It landed on the desk with a flutter. Her stomach churned. She was glad she hadn’t eaten.

“I don’t understand …”

“It guarantees we don’t write each other’s stories in here. When you’re finished with your draft, one of the final reviews of the Post Completion committee is testing the ink against your blood sample.”

“Why not just record us writing?”

“Recordings can be edited. Blood doesn’t lie. It’s the only way to guarantee no one ever tells a story that is not their own.” The woman turned back to her typewriter and began click-clacking away.

Barbara stared at the woman’s hands, how they moved so fast and steadily across those keys. Was it possible the woman had built up a tolerance for the pain? Or maybe she just didn’t care? Or maybe she believed in her story enough to tolerate the pain? She thought of the man she’d seen leaving this room earlier, his hands clenched in his pockets, not even taking them out to call the elevator. Had they been covered in blood like hers? Like this woman’s? Barbara thought of her Jenny. Did she believe in her enough to get through this? Did she want to know what was happening between Jenny and her friends enough to write the story to find out? She didn’t know how long it would take her to write it. How many days of this could she survive? Was her dream of being a published author, a COAC artist, really worth this?

The woman stopped and looked up at Barbara. Barbara wondered if the woman was seeing a younger version of herself, when she’d first walked through those doors and found this world. Who had been in this room to explain it to her then?

“It’s really better if you just sit down and do it. Don’t stop, don’t think, just bleed. The writing will come faster than you think.”

A Great had said something like that — Barbara couldn’t remember which one now. Something about a typewriter and bleeding. She thought of her bookshelves at home, the works of the Greats lining row after row, the stories that had made her believe in the power of the written word. She wanted her name to rest beside theirs on the shelf, but she knew her name never would. She didn’t belong to the era of the Greats, when artists could tell the stories of those beyond themselves. Her name would be on a different shelf, one with her contemporaries who all played by the new rules. All the COAC writers fit on one shelf still. But at least she could share the same piece of furniture as her heroes.

She would have to be stronger than this pain if she wanted that dream to be a reality. She clenched her fists. She sat back down in her seat. She opened her hands to see her palms a rusty red.

“What about the others?” There were several floors in the COAC building.

The click-clacking continued. “All writing is done on typewriters like these. Dancers choreograph with bloody feet. The visual arts have blood mixed in with their pigments. Have you noticed how any new published artwork all seem to have a reddish tint?”

Barbara hadn’t. She wasn’t a visual art person. She heard her stories before she saw them. She’d heard some of the graduate students complain though that all the new works in the museums were all the same, realistic paintings of realistic events, no imagination in sight. It was too risky.

“Why did it to come to this?”

The click-clacking stopped. Silence filled the room. Barbara wished she could disappear into it, but she wanted an answer as well. Maybe if she heard it, it would make some sense of this.

“They didn’t want to deal with the public anymore. The publishers, the editors, the producers. … You’d think they would have been able to come up with a different solution, but apparently not. It was either this or no new art at all. COAC makes sure art still gets made, so long as it’s the right kind.”

The woman resumed her work, typing with a fury, a ding following soon after. She switched out her completed page for a fresh clean blank one. The margins were already smudged with blood from her fingertips.

Barbara picked up her almost-finished page and sat down. She faced her typewriter again and rolled the paper back in. She grabbed the arms of her chair, not caring if she stained the fabric, and pulled the seat forward. She put her fingers to the keys and pressed down. She counted, maybe then the end of the line and the pain would come sooner.

One word. Two words. Three. Four. Ding. A new line. One word. Two words. Three. Four. Five. Six…

Everything flowed.

Featured image: Rom Chek / Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This story gave me the creeps, I have to tell you. Without reading much in the beginning I had to scroll down to see what COAC stood for, then go back to the beginning which I did. It’s really a horror story, yet from what I hear about U.S. Universities, maybe it’s not as uncommon or unthinkable as I might think at all. Since you’re the writer, I’d love you to tell me in a response, please. Some of this has to be based on fact. Maybe not, but I’d like to know.

I liked your writing style that made you feel the characters’ mental/physical/emotional state, the conversational style and descriptive physicality of the surroundings and items. Thank you.