William Saroyan was hailed by Kurt Vonnegut as the “greatest of all the American minimalists” for his simple stories about childhood, the immigrant experience, and Fresno, California. Saroyan won both a Pulitzer Prize and an Academy Award. He wrote plays, novels, and short stories based on his travels across Eastern Europe and his experience of living as an Armenian immigrant in Northern California. Saroyan’s stories elicited hard-to-come-by optimism during the Great Depression, and he maintained a prolific, celebrated career until his death in 1981.

Originally published on September 11, 1965

Anybody with a dime in his pocket when everybody else has only a penny or nothing at all is likely to think twice about how to spend it, or what to save it for, or how to behave toward his friends.

The man with the dime in his pocket was Hearap Bashmanian, who came slowly to the front lawn of the Korkmazian house at San Benito and M streets where four other boys were sitting and talking about money. Two of them had a penny each, one had two pennies, and one had no coin at all.

“What are you guys talking about?” Hap said.

“Money,” Korkmazian’s boy Ara said.

“What about money?”

“Whether it is better,” Sharkey said, “to save or spend.”

“And whether it is better,” Reuben Malatian said, “to earn or steal.”

Hap had a rather interesting reputation as a stealer, so that Reuben’s remark, although earnestly made, amused the others, who discreetly kept their amusement to themselves, while Hap, as expected, pretended that he knew nothing about stealing at all.

“Earn,” Hap said. “Earn and the world likes you; steal and the world hates you.”

“Sure,” Ara said. “But earn and you get tired. Steal and you get more, and don’t get tired.”

“Steal what?” Hap said. “Whatever’s around,” Reuben said. “A man gets a good eye for what’s around to steal, and pretty soon he’s got money in his pocket. How much have you got in your pocket, Hap?”

“A dime.”

“All I’ve got is a penny,” Reuben said, “which I earned by going on an errand to town for my father. How did you get your dime?”

“Errand for my father, too.”

“One errand?”

“Five. My father gives me two cents an errand — one cent each way.”

“How come your father sent you on so many errands?”

“Five isn’t so many.”

“To town and back, five times? From your house it’s seven blocks each way. You didn’t have a dime when we were all on this lawn this morning, so right after lunch you’ve made a dime from going on errands for your father. Have you made five round trips to town since this morning?”

“Sure. What’s so hard about that?”

“You’re not telling the truth,” Sharkey said. “Maybe you haven’t got a dime.” Hap showed the dime. “All right, how did you get it?”

“I told you.”

“It’s a lie.”

“Stand up and fight if you’re going to call me a liar,” Hap said.

“I’m going to sit right here and not fight, because every time I fight I get hit in the nose,” Sharkey said.

“Take it back, then.”

“You’re not a liar, Hap. Now, how did you get the dime?”

“I found two burlap sacks back of the bakery and sold them for a nickel each to the junk guy over on Railroad Avenue.”

“The San Joaquin Bakery?” Reuben said.

“On the loading platform,” Hap said.

“Are you sure you didn’t steal them from inside the place when nobody was around?” Sharkey said.

“No, they were on the loading platform. I was on my way to the California Playground. I picked them up. I took them to the junk guy. I sold them.”

“What are you going to do with the dime?” Ara Korkmazian said.

“I don’t know.”

“Let’s spend it,” Vahan Bazoyan said.

“Why should I spend my dime? You guys spend your money if you want to; I’m going to save mine. I’m going to walk past the loading platform at the San Joaquin Bakery six or seven times a day, and if there’s a sack out there or two sacks, or maybe three, I’m going to pick the sacks up and take them straight to the junk guy on Railroad Avenue and sell them for a nickel apiece until I’ve got a silver dollar.”

“Easier said than done,” Sharkey said.

“I’ll have me a dollar one of these days.”

“What are you going to do with the dollar, Hap?”

“Save it.”

“Thrift,” Ara said, “makes the heart grow fonder.”

“Absence,” Reuben said. “Not thrift.”

“Thrift too,” Ara said. “Save money and you grow fonder of money than ever before. The more money you get, the fonder you get. Hap, you keep stealing those sacks from the San Joaquin Bakery and you’re going to be one of the richest nine-year-old boys in the whole city of Fresno.”

“I don’t steal,” Hap said. “I take what people throw away and I sell it to the junk guy on Railroad Avenue.”

“You’re going to be so rich, you’re not going to want to talk to us poor guys any more,” Vahan said.

“I’ll talk to you guys.”

“Easy to say; not easy to do. We’re friends, but you’re not a friend,” Sharkey said. “A friend with a dime on a hot afternoon in July would go across the street to Eranose’s grocery and buy a nice cold watermelon and bring it over to this lawn and cut it up and give us each a big slice.”

“You guys put your money together and go and buy a watermelon from old Eranose and give me a slice.”

“You’re not a friend,” Ara said. “The rest of us are friends to one another, but you with your dime, you’re not a friend, you’re just a passerby.”

“You’re just visiting the poor people,” Reuben said.

“You’re just visiting the slums, that’s all,” Sharkey said.

“I want to be rich,” Hap said.

“You are rich,” Reuben said, “and like all rich people you don’t care about the poor people.”

“I’m not going to buy a watermelon.”

“Buy a brick of ice cream, then.”

“I’m not going to buy anything. I’m going to keep my money.”

“You’re a miser.”

“Stand up and fight, Reuben.”

“It’s too hot to fight.”

“Take it back, then.”

“You’re not a miser, Hap, you’re just cheap.”

“Stand up.”

“All right,” Reuben said. “You’re not cheap, either, so what are you?”

“I’m thrifty. Industrious and thrifty, like Miss Chambers at Emerson School said the Armenian people are.”

“Artistic, industrious, and thrifty is what Miss Chambers said,” Sharkey said, “because I was there, and she said it to me, because she wanted to know how it had happened that I, also an Armenian, wasn’t artistic, wasn’t industrious, wasn’t thrifty. Well, it just happens that she doesn’t know that the Armenians are also funny, they know how to have fun, how to make comedy, how to tell funny stories, how to say funny things. I’d rather be funny than rich.”

“I’d rather be rich than funny,” Hap said.

“You will be rich,” Sharkey said. “But whether you like it or not, Hap, you are always going to be funny too. You don’t even have to try. You’re funny when you don’t mean to be. You’re funny and don’t even know it.”

“Get up and fight,” Hap said.

“Ah, come on, I take it back. I take it all back. You always want to fight.”

“Honor,” Hap said, “is more important to the Bashmanians than anything else.”

“Except money,” Ara said, “and I take it back too. We were having a nice time here, being poor and talking, so you come up with your dime and spoil everything. Hap, just try to remember this is 1919. The war’s over.”

“What’s the meaning of that crack?”

“Live and let live is the policy all over the world now. Don’t flaunt your wealth.”

“I’m not flaunting it.”

“Yes, you are flaunting it.”

“I’m keeping it.”

“That’s the worst kind of flaunting there is, Hap. It’s very rude.”

“I came up here,” Hap said, “and you guys asked me how much money I’ve got in my pocket, and I told you — a dime. And ever since, you’ve been trying to get me to buy a watermelon from Eranose. If you really want a watermelon, why don’t we all take a walk to the San Joaquin Bakery and see if there are any sacks on the loading platform; and if there are, the junk guy on Railroad Avenue will give us a nickel each, and then we can come back and buy the watermelon and eat it.”

“All of us take a walk?” Sharkey said.

“Sure. All of us are going to eat the watermelon. Come on. By now maybe they’ve thrown away two more sacks — maybe three or four, even.”

There were no sacks on the loading platform, but just beyond the sliding door there was a bundle of them, held together by wire, and nobody around. Hap jumped up onto the platform, lifted the bundle, tossed it to the group, Sharkey caught it, and everybody began to run toward the California Playground. They kept running until they reached Levy-Zentner’s Produce, where they tugged the sacks free from the wire and counted them.

“Twenty-five,” Hap said. “Five sacks each. Twenty-five cents each.”

“You and I did all the work,” Sharkey said. “Why should we cut them in?”

“We’re all in this together — this good luck of finding twenty-five sacks,” Hap said.

Each of them presented five sacks to the junk guy on Railroad Avenue, and he handed each of them a quarter. Then they went back to the cool and shaded front lawn of the Korkmazian house at San Benito and M streets and stretched out to rest a minute. At last Hap said, “Well, who’s going to buy the watermelon from Eranose?”

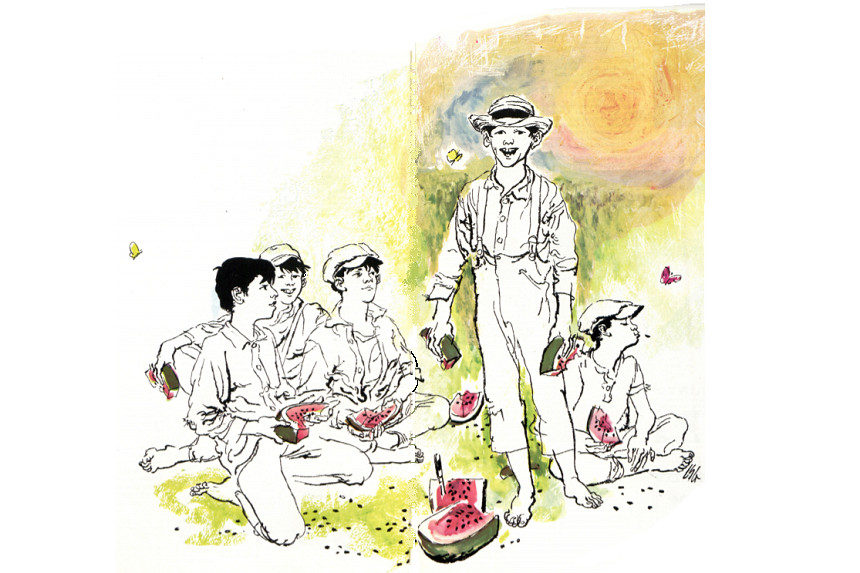

Almost in one voice, each of them said, “I will.” But it was Ara Korkmazian who simply got up and went across the street to the little store. The watermelon he brought back was delicious, but while they were eating it Sharkey said something funny about seeds that made them all start to laugh as if they were laughing for the first time in their lives, and it seemed as if they couldn’t stop. They didn’t stop until Ara’s mother came out on the porch and looked at them. She just looked. Then, they stopped.

“Ara,” Hap said, “what’s your mother mad about?”

“Me, I guess.” He got up and started walking across the street again.

“Where you going?” Reuben said.

“I’m going to buy another watermelon. The biggest one he’s got — for fifteen cents.”

“What for?” Sharkey said. “ Why should you buy all the watermelons — spend all your money?”

But Ara was gone, and he soon came back with the biggest Klondike watermelon anybody ever saw. They cut it and ate it, and then Hap said, “Ara, it wasn’t your turn to buy the second watermelon. What did you do it for?”

“I felt like it.”

“Why?”

“I don’t know. I just felt like it.”

But everybody knew that he had spent all of his money because he hadn’t wanted to have that kind of money in his pocket. Hap Bashmanian rather admired him, but he thought, “He’ll never be a millionaire.”

Illustrations by Louis Glanzman

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now