Although the Olympic Games are all about sportsmanship and athleticism, they’re also about the unexpected. In the lead-up to the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, South Korea, one Post contributor decided to take a look at some of the stranger competitions and lesser-known stories to come out of the Games.

The text of this article was originally published in the July/August 1988 issue of The Saturday Evening Post

Imagine a Summer Olympics that offers spectators such exciting events as underwater swimming, a standing hop-skip-and-jump, live pigeon shooting, Finnish baseball, or a 100-meter swim limited to Greek sailors. Or how about a schedule that includes such never-to-be-forgotten contests as Australian football, dueling pistols, croquet, field handball, or running deer-shooting?

Don’t laugh.

Since the introduction of the modern Olympics in 1896 in Athens, Greece, all those sports have been on the calendar of the Summer Games at one time or another. In the 92 years preceding the upcoming XXIVth Olympiad, scheduled for September 17-October 2 in Seoul, South Korea, more than 125 individual and team events have surfaced briefly. Some bobbed up only long enough to embarrass themselves, such as the live-pigeon-shooting event at the Paris Games in 1900. A Belgian sharpshooter won the competition by killing 21 birds. This cruel Olympic sport was then barred forever.

The 2,000-meter tandem cycling race enjoyed a much longer life. It was held at 13 different Summer Olympics before being eliminated following the 1972 Games in Munich, West Germany.

Track and field leads the discontinued events with 27, followed by archery, shooting, gymnastics, and swimming. Some of those long-gone events and discontinued sports once held special significance for the United States. Golf is a prime example. By capturing the nine-hole women’s event at the 1900 Paris Games, Margaret Abbott became the first U.S. female Olympic champion. Oddly enough, she didn’t win a gold medal. That’s because the 1900 Games were the only Olympics in which no such medals were awarded; the winners received valuable artifacts instead.

In the two Olympics in which golf was played — 1900 and 1904 — the United States dominated by annexing eight “medals” and sweeping the team title at St. Louis in 1904. “Golf was discontinued because it wasn’t really an international sport at that time. Only three countries participated in those early Olympic tournaments,” says C. Robert Paul, Jr., the U.S. Olympic Committee historian. Other discontinued sports in which Americans excelled included lacrosse; tennis; lawn tennis; rogue (a variation of croquet); rugby; military, miniature, and free-rifle shooting; polo; cricket; and tug of war.

Rugby disappeared from the Olympics following a near riot in 1924. After the U.S. rugby team crushed the favored French in Paris to capture the gold medal for the second consecutive Olympics, police had to escort the victors from the field. The French booed so loudly at the awards ceremony they drowned out the playing of the national anthem. Of course, the decision of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to discard rugby was also influenced by only three nations entering rugby teams in 1924 and two in 1920.

Remember the old TV series The Rifleman, starring Chuck Connors? Well, America’s Carl Osburn was a real-life rifleman from Ohio. A U.S. Naval Academy graduate who eventually became a commander, Osburn earned 11 medals in three Games from 1912 to 1924, more than any shooter in Olympic history. Many of his medals were for events later discontinued.

Tennis vanished after the 1924 Games, in which the legendary Helen Wills — considered among the greatest female players in history (victories in 31 major championships) — won two gold medals. From 1896 to 1924, U.S. Olympians had captured 15 tennis medals. Unlike most other discontinued sports, tennis — including world-class professionals — has been reinstated for the Seoul Olympics.

Why is tennis the odd sport “in”? Paul explains: “Back in the ’20s, millionaire Dwight Davis, the vice president of the U.S. Olympic Committee and the man for whom the Davis Cup is named [also the president of the U.S. Lawn Tennis Association], along with the All-England Championships — which we know as Wimbledon — were afraid the Olympics were going to control the game of tennis. They felt the sport would fail to grow in the U.S. and England as long as it was part of the Olympic program. So they made an economic decision to withdraw the sport from the Summer Games.

“Tennis has been resurrected because IOC President [Juan Antonio] Samaranch and the International Tennis Federation now feel the sport and the Olympics will jointly get tremendous worldwide publicity from allowing well-known professionals to compete at Korea.”

As the result of such Seoul-searching, many of the world’s best tennis pros have been sanctioned to play in the Olympics, including West Germany’s Steffi Graf and Boris Becker, Sweden’s Stefan Edberg and Mats Wilander, Argentina’s Gabriela Sabatini, and America’s Tim Mayotte and Pam Shriver.

Although many Olympic sports have slipped from sight forever, others have moved in to take their places: volleyball, handball, judo, freestyle wrestling, and synchronized swimming. The IOC won’t admit a new men’s sport unless it is widely practiced in at least 50 countries on three continents.

Joining tennis as “newcomers” at Seoul will be table tennis, as a full-fledged addition to the Olympic program; baseball, women’s judo, and tae-kwon-do (a form of judo) as demonstration sports; and bowling and badminton as exhibition events. No medals are awarded in demonstration and exhibition competition.

The history of the Summer Games is filled with “the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat.” Some of that has occurred in such oddball sports as rugby and tug of war, and still others in such mainstream events as track and basketball.

“Disgusting and sheer robbery” is how Paul, an onlooker at six Olympics since 1960 as both a historian and a spectator, describes the outcome of the championship basketball game in the 1972 Munich Olympics between the U.S.S.R. and the United States. The Americans had apparently won the game, 50-49, with three seconds remaining, when Doug Collins, now the coach of the NBA’s Chicago Bulls, sank two free throws. But a controversial ruling by an official gave the Soviets additional seconds on the game clock, and they converted a basket to win the game and the gold medal, 51-50.

“It was the worst thing I’ve ever experienced in the Olympics,” says Paul, whose blood “still boils” over the subject. “The IOC broke every rule in the book and cheated the Americans out of the gold medal. It was shameful.” (Paul adds that the U.S. coach, Hank Iba, “was robbed again” in the confusion that followed the game. A light-fingered thief managed to lift $370 from Iba’s pocket while he was busy signing the official protest form.)

Controversy has been an American trait in the Summer Games. At the 1908 Olympics in London, the U.S. tug-of-war team pulled out of the competition after its first-round loss to the Liverpool police. The Yanks claimed that the Liverpool team was wearing illegal boots. Not so, said Olympic officials. Liverpool went on to capture the silver medal. After two more Olympics, tug of war was yanked from the ranks of world-class sports.

The American Margaret Murdock — a markswoman who could read only the top line on an eye chart — appeared to have won the gold medal in the small-bore rifle, three-positions event at Montreal in 1976. Her final score was 1,162 points; her teammate Lanny Bassham had 1,161. Before the medals could be awarded, the shooting officials announced they had made a mistake. The two Americans were actually tied at 1,162 points.

The International Shooting Union awarded Bassham the gold medal because his last ten shots had been more accurate by a fraction of a millimeter. So Murdock’s golden performance was only good enough for a silver medal. This plucky Kansas nurse was still delighted. After struggling for years in a predominantly all-male sport, she had become the first female Olympic shooting medalist.

When it comes to gymnastics, millions of sports fans are familiar with the name Mary Lou Retton. At the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, this 4’9″ dynamo collected five medals. The bubbly Retton, the youngest U.S. gymnast to win an Olympic medal, will be a commentator for NBC Television at Seoul.

George Eyser was born too soon for such an opportunity. In 1904 in St. Louis, the American gymnast won six medals in such events as rope climbing, horizontal bar, and parallel bars while heroically competing with — a wooden leg.

Television would have loved such drama. But the Olympics weren’t televised until the Berlin Games of 1936, and then the telecasts were shown only in Germany. U.S. television coverage began in 1960.

Like Eyser, many U.S. Olympic heroes have gone unsung because they competed before the age of television. For example:

- Eddie Eagan is the only American to capture gold medals in both the Summer and the Winter Games. This Yale graduate and Rhodes scholar won the light-heavyweight boxing title in Antwerp, Belgium, in 1920, and in 1932 he was a member of the winning four-man bobsled team at Lake Placid, New York.

- Marjorie Gestring is America’s youngest-ever gold medalist. She was 13 years and 9 months when she took the springboard-diving event in the 1936 Games. Conversely, Galen Spencer is the oldest U.S. gold-medal winner; the archer scored his victory at age 64 in 1904.

- Although the American fencer Janice Lee Romary never won a medal, she competed in more Olympics than any woman in history. Her string extended from 1948 to 1968.

Following unprecedented gymnastic performances from 1956 through 1964 at Melbourne, Rome, and Tokyo, the Soviets’ Larissa Latynina leads all Olympians with 18 career medals. That’s 7 more than Osburn and the U.S. swimmer Mark Spitz have won. [This record would later be blown out of the water in the water by Michael Phelps, who has won 28 Olympic medals — 23 of them gold.]

The Summer Olympics would seem an unlikely setting for romance. The crush of athletes, officials, journalists, and spectators makes privacy virtually impossible. But an American hammer thrower, Hal Connolly, and a Czechoslovakian discus champion, Olga Fikotova, fell in love while both were winning gold medals in the 1956 Olympiad in Melbourne. After marrying, the couple competed for the United States as husband and wife in the next three Olympics. But neither won another medal. And following their divorce in 1975, Connolly married another Olympian.

Surprisingly, many married American couples have competed in the Olympics. Combining for four medals in the 1920 and 1924 Olympics were a swimmer, Frances Schroth, and a water-polo player, George Schroth. Andrea Mead Lawrence and her husband, David, were both alpine skiers in the 1952 Winter Games at Oslo, Norway, where she became the first U.S. skier in the history of the Games to win two gold medals in Alpine skiing.

Then there are the cyclists Davis Phinney and his wife, Connie Carpenter-Phinney. Davis managed a bronze medal in a 100-kilometer team event in the 1984 Games at Los Angeles. Connie was not only a gold medalist in the women’s inaugural road race in the same Games, but she is also the only U.S. female to compete in both the Summer and the Winter Olympics, having been a speed-skater at the 1972 Olympiad in Sapporo, Japan.

Indeed, so many unusual things have happened in the 92-year history of the modern Summer Olympic Games that they deserve their own version of Trivial Pursuit.

—Originally published in our July/August 1988 issue of the Post.

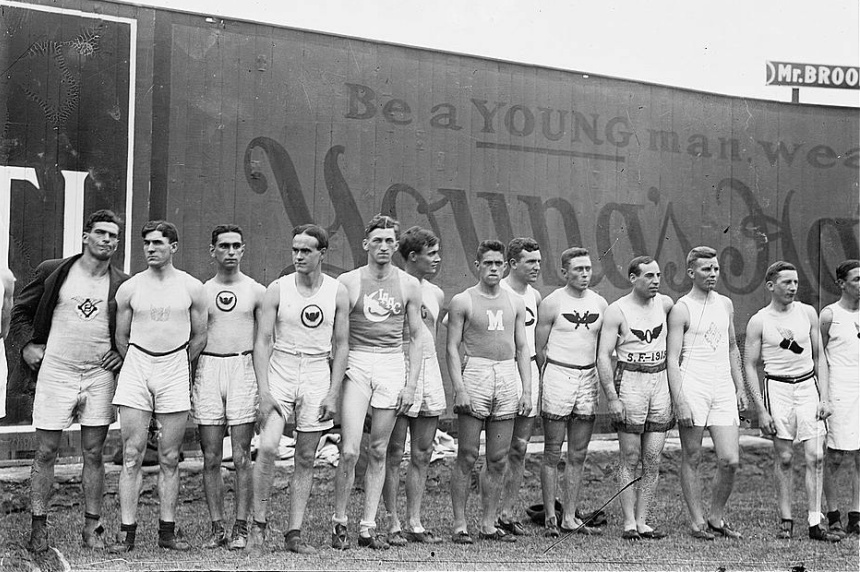

Featured image: Olympic athletes from the 5th Olympic Games, held in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1912 (Library of Congress)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Really appreciate the insights, great job on this blog!