Despite the machinations of the Central Park groundskeepers with their noxious, peace-shattering blowers, there are still enough leaves on the ground for me to wade through, ankle-deep, shuffling my feet to make a whoosh-whoosh sound, and sending upward a papery, tobacco-y scent; my nose knows that autumn is drawing to an end, and winter is coming.

I had forgotten the change of season, the sounds and scent of brittle leaves, after living for nine years in Costa Rica. My re-awakened senses conjure up memories of my childhood in Duluth, Minnesota.

My neighborhood had big yards, with lots of trees that shed lots of leaves for months, starting on Labor Day. We kids buried ourselves in leaf piles that our fathers had dutifully raked up; I emerged with enough flakes and bits stuck in my hair and clothes to send my mother into conniptions. On November Saturdays the family activity was re-raking those piles of leaves into the street gutter where they were set ablaze, the reward for weeks of yard work.

Families gathered in the street in the darkening afternoon to watch their labor turn to ash, the dads smoking, the moms exchanging gossip and hot dish recipes (“You take a can of Campbell’s Cream of Mushroom…”), in between bouts of yelling at rampaging kids. Burning leaves in the street, in close proximity to kids and cars, unlike the dangers of frayed electrical cords and oily rags in your basement, was never mentioned in Fire Prevention or by Smokey the Bear.

The leaf-burning ritual signaled that it was time for the snow to arrive. I don’t remember anyone greeting those first flakes with less than unbridled glee. Winter in Duluth was like childbirth: you can’t seem to remember the pain of the last time around.

When your home is the 47th parallel on the shores of the greatest of the Great Lakes, Superior, you pretty much have to love winter. Otherwise you’d go mad.

And maybe parents did back then, driven round the bend by February over the endless shoveling, automobiles stuck in snowbanks, frozen water pipes, and dead car batteries, drowning their insanity in bourbon and ginger behind closed doors.

For kids, winter was a paradise; we were tiny Shackletons and Byrds, undaunted by the cold. You know how children can amuse themselves at the beach for hours with nothing more than sand and a bucket? That was us Lakeview Avenue kids and snow. We couldn’t wait until there was enough snow on the ground to build a snowman. This was a team effort, rolling balls of snow like dung beetles, stacking the three balls on top of each other, finding the perfect sticks for arms, and dashing into the house to filch snowman accessories. Our snowmen never came close to looking like Frosty: even if someone scored a limp carrot for the nose, we had no lumps of coal or top hat, and mothers repossessed the scarf, muttering “Damn kids.”

We borrowed shovels from the garage intending to erect elaborate snow forts. The snow forts were never finished, our Sagrada Familia. At some stage of construction, the first snowball was lobbed over the two-foot wall. And of course, you know, this means war.

The perfect snow for making snowballs is not the light, fluffy, pretty snow. To get a good dense projectile, you want snow that is thick and wet, so it slightly melts and sticks together as you roll, pat, and squeeze it between your hands. Since all mittens were knitted wool, after a good volley of snowballs they were soaked with 33-degree water and my fingers were too numb to move. I was forced back inside my home, where I peeled the soggy mittens off to reveal bright red fingers, dropped them on the mud room floor, and searched in the box by the door for two others. Once I had gone through all the mittens I could find, I was stuck inside: time to make cocoa. Chocolate milk was frowned on in my home, but hot chocolate was okay. I spooned Swiss Miss into milk heated too high on the stove, until a thin disgusting skin formed on the surface. I swirled it onto the spoon and threw the mess into the sink, to be followed by a slightly scorched pot. We never had marshmallows or Reddi-Wip in the house, a mistake I did not repeat with my own children.

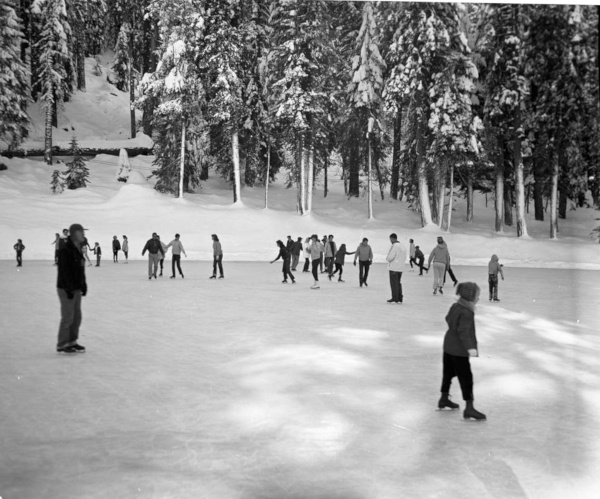

Homemade cocoa was never as good as the fifty cent cocoa at the ice rink. The Longview skating rink was where you could find every kid in the neighborhood on a Saturday. (Again, my mom considered the roller rink a fount of debauchery, but ice skating was good clean fun. The mysteries of families.)

Longview was the frosty site of pre-teen flirtation. Pom-Pom-pullaway (known to the civilized world as crack the whip) was theoretically forbidden, with good reason: when an undersized child like me was on the end of a line of manically speeding kids and lost her grip, she was flung into the siding at about thirty miles per hour.

But despite the rink attendant’s best efforts, illegal Pom-Pom-pullaway persisted, because it offered the thrill of boys and girls touching hands through two layers of mittens.

You knew a boy liked you when he flew past on his hockey skates and snatched your hat. My hat remained forlornly on my head, while the hatless twelve-year-old girls squealed and made hopeless attempts to catch up to their prospective beaus so they could pretend to be angry.

I don’t remember any skate rentals; we all had our own skates, which required every bit of strength my own stick arms had to lace up tightly enough to prevent my ankles from flopping over to the sides.

Back before the invention of the buckle, ski boots also laced up. And if they weren’t laced tight enough, snow not only completely encrusted the laces, it got into the top of your boots where it melted and soaked your socks.

We took our downhill skis out in all temperatures, from below zero to the balmy thirties, when I skied in jeans and a sweater and thought I looked cool.

The closest ski area was tiny Mont du Lac, the miniature golf of skiing. Mont du Lac had three runs: a beginners’ slope, aka the bunny hill, an intermediate slope, and a slightly advanced (but still terrifying) run that could be descended in under three minutes.

There were two ski lifts, and neither of them was the chair. There was a rope tow, which tended to yank me face first into the snow; and the dreaded T-bar, an infernal invention that required the grace and balance of Simone Biles not to tip. Too often before reaching the top the unlucky person sharing the T-bar with me and I both went ass over teakettle. I would land on my back in the hard-packed snow, my boots popping out of the bindings; only a thin leather strip kept the skis from shooting downhill and impaling someone. On both lifts, I was often the cause of a multi-kid pile up.

My parents considered skiing enough of a treat; buying a hamburger from the chalet grill (the mouth-watering aroma of sizzling meat and onions almost overpowering the smell of wet wool) would have been gilding the lily. The Haubner family packed a lunch.

By noon I had fallen up and down Mont du Lac a dozen times. To get to my bologna on Wonderbread, no mayo no mustard, and the resuscitating plaid thermos of cocoa, I had to first fumble through my mittens to unlatch my skis from the bindings, clumsily pick them up (thus covering myself with more snow), and lean them against the fence before I could clomp into the fuggy chalet. It was expected that anyone over the age of six could handle her own skis.

Once inside, I removed my frozen-stiff mittens and tried to rub warm blood into my close-to-frostbit fingers and feet, ate my lunch with my mom, a committed non-skier who stayed inside with that month’s Ladies Home Journal, looked longingly at the jukebox and pinball table (both a dime and both verboten), then headed back outside, skiing till the early dusk turned the snow violet, the rope tow and T-bar slowed and stopped, and it was time to fumble my skis into the trunk of the Chrysler.

The other winter sport that relied on gravity was sledding. The rolling hills of Northland Country Club were the perfect sledding venue; there were no “No Trespassing” signs, and thoughts of risk and lawsuits must have never entered anyone’s head — you didn’t even have to be a Northland member to sled there.

On weekends tiny tots were whizzed downhill on twirling Flying Saucers during the day; at night drunken teenagers tobogganed in the dark, inevitably hitting a mogul and catapulting into the air — usually harmlessly.

My mind holds snow globes of Duluth winters. The winter my dad hosed down our backyard, transforming it into an ice skating rink, and how he sulked when I still preferred Longview, with its snack bar and unattainable boys. The overnight ski trip I took with a friend, where we etched the first tracks down the slope on the perfect winter morn, nothing but glistening white snow and cerulean sky. The time my hippie pals and I went snowshoeing in the woods while tripping on acid, unable to feel our faces or to stop laughing. The night we went through quite a bit of deadly Tango orange-flavored vodka and a girl (was it Andie?) getting her front tooth knocked loose in a tipsy tobogganing incident; thank goodness one of the sledders was not too drunk to remember that his dad was a dentist.

I tried to recreate the less dangerous sledding experiences of my childhood with my own sons, even though we lived in the polar opposite of Duluth: New York City.

A sledding excursion required first wrangling a two-year-old and a three-year old into their snowsuits, which they fought every bit as much as they did the application of sunscreen; children believe they are imperious to the elements. My belting out “There’s No Business Like Snow Business” in my best Ethel Mermen while stuffing their arms into sleeves only made them cry harder.

I wrangled two toddlers and two plastic saucers on to the uptown bus (only then realizing that the thermos of cocoa was still on the kitchen counter), our destination one of the few hills in Manhattan, in Central Park behind the Metropolitan Museum.

Sledding used to be one of New York City’s great equalizers, like the subway, and long ago, the public school system. There would be kids with fancy L.L. Bean wooden sleds with bright red runners, kids with purloined cafeteria trays, and kids with flattened cardboard boxes that bravely made a few trips through the snow before disintegrating.

I’m looking forward to this winter even though my kids claim they are too old to sled and my skiing days are long over — I am tempted to go skating at the Bryant Park rink, just because it’s free.

The days grow shorter, darker, and colder. My dogs’ breath steams behind them as they race off in hot pursuit of every squirrel in Central Park, certain that this time they’ll catch one: the triumph of hope over experience, a trait I wish I shared. My skiing and sledding and maybe even skating days are behind me, but I rejoice in the cold, especially on dawn patrol with the pups. I gulp the frigid exhilarating air deep into my lungs, my eyes blink back tears, my nostril hairs tingle as they freeze, and I know the boreal wind is putting roses in my cheeks.

Winter is the gift of one more season in my life, another reason to be grateful that I still walk through this wide, wonderful world.

Featured image: IgorGolovniov / Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Growing up in So Cal (Southern California), snow was only in the movies. So reading your latest entry affirmed I never would have made it!! I had to put on a sweater just to get through it!

Keep writing Gay, you make me laugh and feel nostalgic and even a little melancholy—all good on a chilly Caribbean morning.

My dad tried to hose a rink in Ann Arbor and it was too bumpy to skate!

Another great slice of life from your girlhood up in Minnesota I’m enjoying vicariously. Good to see Pat, Mark and Brooke commenting here, as they did during the ‘North Country Girl’ series and some of your subsequent features.

I’m afraid winter tire sledding a few times at Frazier Park and ice skating in nearby Northridge and North Hollywood is about the closest I got to ‘cold’ activities at this time of year! Stay well with this nightmare getting worse, unfortunately. We all look forward to your next life story experience here on the Post website, Gay. Until then, keep plenty of hot chocolate with mini-marshmallows handy and a can of that Reddi-Wip!

Thanks for sharing your stories Gay. I don’t know but it’s a little bit of all our childhoods.

Thanks for another great trip down memory lane, Gay! Skiing, sledding and skating our way through ‘ice out’ — I miss them, to this day. Thank you for such lovely mind pictures. Please keep the stories coming.

Thanks Gay I really enjoyed this. I did a lot of winter skating at Lester Park, stealing girls hats and playing “crack-the-whip” (I don’t remember it being illegal at our rink). For me the memory of “sweet fragrance of burning wool on the pot-belly stove” mentioned above is always accompanied by the memory of the excruciating pain my frozen feet went through thawing out in the warming shack.

Gay, you are spot on about the Minnesota memories! We were so fortunate to grow up in the Northland. As always, l devour your articles.

Gay, once again you’ve captured the essence of childhood in the 50’s & 60’s in Duluth!

Those of who grew up playing hockey would only add the ‘sweet’ fragrance of burning wool on a pot bellied stove!

Winter acquaints you with life and survival. After sixty years of surviving Chicago winters, I returned to my south Florida roots where the survival that concerns me is that of my aging Margarita blender. Time passes softly where the tropics begin; in a really cold winter, I might have to buy socks.