This is the second installment of a three-part series on how our state capitals got their names. This week, we continue our toponymic trek by looking into the histories (alphabetically by state) of Frankfort, Kentucky, through Raleigh, North Carolina. Here you’ll find red sticks, pig’s eyes, presidential eponyms, and more than a few recycled city names.

Follow these links to read Part I — Montgomery, Alabama, to Topeka, Kansas, and, when it becomes available, Part III — Bismarck, North Dakota, to Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Frankfort, Kentucky

If you thought (like I did) that Frankfort simply meant “French fort,” you’d be just as wrong as I was.

In 1780, when what would become Kentucky was still a part of Virginia, it seems a settler named Stephen Frank was killed during a skirmish with a native tribe near a site where the Kentucky River was shallow enough to wade across — that is, they could ford the river. Stephen’s compatriots took to referring to the place as “Frank’s ford,” which became Frankfort in 1786 when the Virginia legislature designated the land for the creation of a new town.

This means that Frankfort is etymologically linked to Hartford, Connecticut.

As a surname, Frank could trace backward in a few directions, landing at words meaning “free,” “noble,” “lance,” and yes, “Frankish” or “French.” Ford — the crossing of a river by walking — has been around since Old English.

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Louisiana’s capital is called Baton Rouge because of a border dispute. The Houma and Bayougoula — neighboring tribes along the Mississippi — were living close enough that they were hunting on each other’s land. At least that’s what each tribe believed. To settle the dispute, they embedded a large cypress pole on the east bank of the river to mark the boundary between their respective hunting grounds.

In 1699, the French-Canadian explorer Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville, while making his way upriver, saw the pole, which was surrounded by animal parts and stained with blood. In French, it was le bâton rouge — “the red stick” — and the name stuck.

Type this capital name carefully; spellcheck won’t save you if you accidentally call it Baton Rogue.

Augusta, Maine

Portland is the largest city (by population) in two states — Maine and Oregon — but it is not the capital in either. But that wasn’t always the case: When Maine became the country’s 23rd state in 1820, Portland was designated its capital. The capital was moved to Augusta in 1832 so it would be more centrally located.

Originally incorporated as Harrington in 1797, the town changed its name to Augusta on June 9 of that year. The common story is that it was named after Pamela Augusta Dearborn, the daughter of Revolutionary soldier and statesman (and later Thomas Jefferson’s Secretary of War) Henry Dearborn.

Augusta comes from the feminine form of the Latin augustus, which means “venerable, noble.”

Annapolis, Maryland

Founded by Puritan exiles from Virginia in 1649, Annapolis was originally called Providence — probably for the same reason Roger Williams chose the name for the capital of Rhode Island (coming in next week’s column). It later became Anne Arundel’s Towne, after the wife of Lord Baltimore. But when the Royal Governor Sir Francis Nicholson moved the colonial capital there, he decided to honor Britain’s heir apparent, Princess Anne, and named the city Annapolis.

The -polis, as we saw with Indianapolis, is a Greek affix meaning “city.” The name Anne traces back to the Hebrew name Hannah, which literally means “graciousness.”

Whether Nicholson chose the name truly to honor Anne or in the hopes of currying her favor in the future, both things happened: As queen, in 1708 she chartered her colonial namesake as a city.

Boston, Massachusetts

In 1630, a group of Puritans left England and headed for the New World, eventually merging with the Plymouth Colony. There were three hills in the area where they settled, so they originally called the settlement Tremontaine (“three mountains”). But many of those settlers had come from the town of Boston in Lincolnshire, England, and eventually they ditched the descriptive moniker and renamed the Massachusetts city in honor of their hometown.

Boston is believed to be a shortening of “Botolph’s Stone,” though who exactly Botolph was we may never know.

Lansing, Michigan

According to an article in the Lansing State Journal, it took a few tries to land on the name for this city, and many weren’t happy with the result. The Michigan House of Representatives passed a bill in 1847 to name the village Aloda, which geologist and ethnologist Henry Schoolcraft said meant “heart of the country” in a local native language.

The State Senate, however, didn’t like it. They dropped that name, and there was a brief attempt to name the village Houghton, after Douglass Houghton, the geologist who discovered massive copper deposits in northern Michigan. But there was already a Houghton County, so that idea failed. Eventually, the Senate decided to just name the town Michigan. Not even Michigan City; just Michigan.

Finally, they settled on the name Lansing. Many settlers had been wooed into Michigan (in a scam, it seems) from their homes in Lansing, New York, so, perhaps a little homesick, they reused the name.

Lansing, New York, was named after John Lansing Jr., who served during his life as the Chancellor of New York, the mayor of Albany, a federal Constitutional Convention delegate, and a justice in the New York Supreme Court. Lansing is a Dutch name that means “family of Lans.”

Saint Paul, Minnesota

That Saint Paul, Minnesota, is named after Saint Paul should come as no great surprise. But how it got that name is interesting.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the area today known as Minnesota was a hotbed for fur traders — at least, for the Europeans who had moved in. The area became part of the United States in pieces: first in 1787 as part of the U.S. Northwest Territory, which was expanded in 1803 as part of the Louisiana Purchase, followed by Zebulon Pike’s purchase of 100,000 acres from the Dakota in 1805. The last parts of modern-day Minnesota were seized by the U.S. government in a series of 1837 treaties.

In 1838, a French-Canadian fur trader and bootlegger named Pierre “Pig’s Eye” Parrant made a land claim and established a settlement called Pig’s Eye Landing — with his tavern as a focal point. Three years later, Lucien Galtier, a French priest and the first Roman Catholic priest to serve the Minnesota area, established St. Paul’s Chapel above the landing. He didn’t like the name Pig’s Eye Landing (who would?), so he named the area after his church.

When the Minnesota Territory was formalized in 1849, the name Saint Paul won out, though some locals still refer to the city as Pig’s Eye.

The name Paul ultimately comes from a Latin word that means “small.”

Jackson, Mississippi

After the State of Mississippi entered the Union in 1817, a site for a new capital needed to be chosen, and legislators wanted a place in the middle of the state. Though it missed the center of the state by a number of miles, the location chosen in 1821 was fertile, beautiful, and well-watered. It was named Jackson in honor of Andrew Jackson and his 1815 victory at the Battle of New Orleans; he would go on to be elected president in 1828.

Jackson literally means “Jack’s son.”

Jefferson City, Missouri

Like Jackson, Mississippi, Jefferson City was chosen and created specifically to serve as a state capital in 1821. While buildings were being constructed, St. Charles, just northwest of St. Louis, served as the capital.

Jefferson City was laid out by Daniel Morgan Boone, the son of the legendary Daniel Boone, and was named for — no surprise here — the then-aging President Thomas Jefferson. The town was incorporated in 1825, and the general assembly moved there in 1826, the year of Thomas Jefferson’s death.

Jefferson, again similar to Jackson, simple means “son of Geoffrey.”

Helena, Montana

In 1864, four Georgians — John Cowan, John Crab, Daniel Miller, and Reginald or Robert Stanley — set out into the Montana countryside looking for gold, but they didn’t have much luck. Ready to give up, they decided they were going to take one last chance looking for gold in a creek, and if that got them nowhere, they were going back home. That last chance they took was the one that did it: They struck gold. They laid their claim at what they called Last Chance Gulch and settled for a time at a place they called Crabtown, after John Crab.

Once news of the discovery got out, fortune-seekers came in large numbers. Crabtown grew, but many of its new residents didn’t take to the name. Quite a few of the newbies had come from Minnesota, and they took to calling it Saint Helena, co-opting the name of another town in their home state. This was shortened to just Helena over time.

Helena traces back to an old Greek name (perhaps you’ve heard of Helen of Troy?) that probably means “the bright one.”

Lincoln, Nebraska

Nebraska’s capital is, surprise surprise, named after a certain well-known U.S. president. But why did Nebraska get the honor? The State of Nebraska was admitted to the Union on March 1, 1867; it was the first new state after the assassination of President Lincoln.

Abraham Lincoln’s surname probably traces back to someone who came from the British town of Lincoln, or somewhere else in the county of Lincolnshire. In Old English, the area was called Lindcylene, from the Latin Lindum Colonia. Colonia just means “colony,” and Lindum is a Latinized version of the British lindo “pool, lake.”

Carson City, Nevada

In the 1840s, the explorer John C. Frémont led five expeditions into the West. During one of those excursions, he came across a river that flowed through Eagle Valley that he named after Kit Carson, a now-well-known trapper and explorer who was serving as Frémont’s guide. Half a dozen years later, in 1851, a trading post called Eagle Station was established, which became Carson City — named after the Carson River which was named for Kit Carson — in 1858. After gold and silver were discovered in the area in 1859, Carson City boomed.

Carson is probably a Scottish surname derived from “Carr’s son.” Carr probably relates to a family who lived near a marsh, because a carre is a marshy place.

Concord, New Hampshire

New Hampshire’s capital is called Concord because that’s what it took to create the city. The town was originally incorporated by Massachusetts as Rumford in 1733, but in 1741, it was determined that the town was actually within the jurisdiction of New Hampshire. Litigation ensued, which ultimately was settled by British courts in 1762. New Hampshire won the town, and in 1765 it was reincorporated as Concord to mark the end of the legal battles.

The word concord, meaning “agreement between persons, harmony,” came to English (through French) from the Latin concors, combining the prefix com- “with, together” and cor “heart.” Concord literally means “hearts together.”

Trenton, New Jersey

The site of Gen. George Washington’s first military victory in the Revolutionary War was named in 1719 for William Trent, who had purchased much of the land from the Quakers who had settled there. Originally called Trent’s Town, the name was shortened to Trenton over time.

William Trent’s name ultimately traces back to the name of a village in England on the Trent River.

Extra trivia: Trenton was the temporary capital of the United States in November and December 1784.

Santa Fe, New Mexico

Most cities whose names start with San or Santa are named — in Spanish — after Catholic saints. The same is true of Santa Fe, but not in exactly the same way. When the city was founded by the Spanish in 1607 — more than a decade before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth — it was officially called La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asis — The Royal Town of the Holy Faith of St. Francis of Assisi. You’ll notice that the city’s current name sits there in the middle. So while Santa Fe was originally named after St. Francis of Assisi, Santa Fe itself means “Holy Faith.”

Albany, New York

Albany was a Dutch community named Beverwyck (“beaver district”) until nearby Fort Orange was surrendered to the British in 1654. It was the British who renamed the city Albany, after the man who was both the Duke of York in England and the Duke of Albany in Scotland. He would later become King James II of England and King James VII of Scotland.

The name Albany derives from a Latinization of the Gaelic name for Scotland, which was later used to indicate specifically northern Scotland. It probably points to a word meaning “white”; one imagines northern Scotland gets a lot of white snow in the winter.

Raleigh, North Carolina

The capital of North Carolina was named after the late 16th- and early 17th-century English nobleman Sir Walter Raleigh. Raleigh never set foot on North American soil, but he did fund the famous disappearing colony on Roanoke Island, off the coast of North Carolina, and twice ventured into South America in search of El Dorado.

The surname Raleigh comes from the name of the British village of Raleigh, whose name derives from Old English ra and leah, meaning “meadow for deer,” which also was probably a good description of Raleigh, North Carolina, when the name was chosen in 1792.

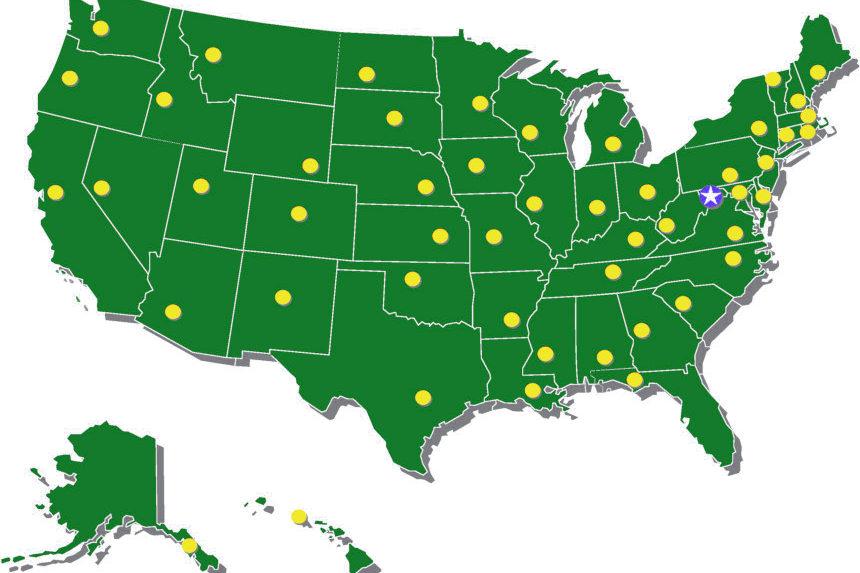

Featured image: Shutterstock

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now