This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-Five:

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

So begins Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride” (1860), one of the most iconic and beloved poems in American history. Since its initial publication in the January 1861 issue of The Atlantic Monthly, Longfellow’s poem has been reprinted countless times and remains a standby in American primary school classrooms, serving as a principal means through which young students first encounter and learn about Revere, the battles of Lexington and Concord, and the first events of the American Revolution.

Longfellow’s poem is engaging and fun — but it’s also significantly inaccurate and mythologized, getting important details wrong or leaving them out entirely. Moreover, the poem’s creation on the eve of the Civil War and the crucial context of Longfellow writing it during that time period are rarely considered. As we celebrate another Patriots’ Day here in Massachusetts and commemorate the battles of Lexington and Concord, challenging those narratives around “Paul Revere’s Ride” can help us recognize the limits of simplified myths and model a far more meaningful form of historical education.

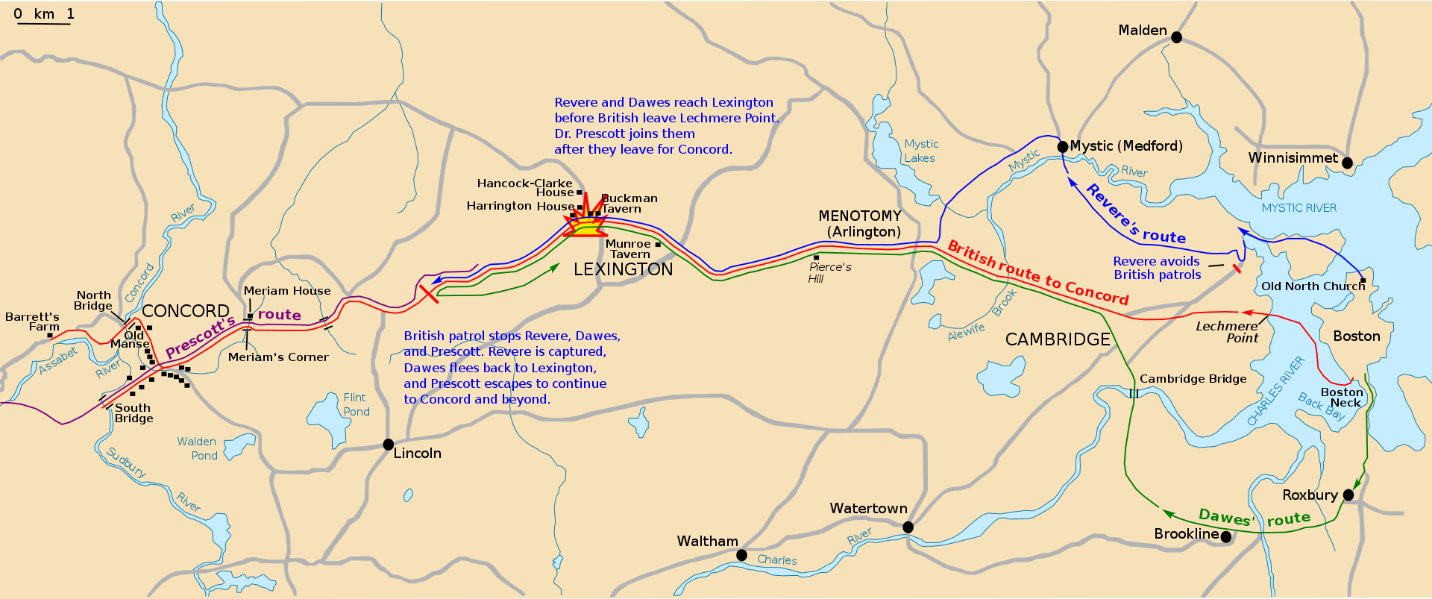

In the climactic verse of Longfellow’s poem, he follows his title subject as Revere completes his midnight ride in a particularly symbolic location. At “two by the village clock” Longfellow’s Revere arrives at “the bridge in Concord town” that would later that same day, as Longfellow notes in the verse’s moving final lines, witness the Revolution’s first battle. It’s a beautiful poetic transition from Revere’s ride to its aftermath and legacy, the American origin point that Ralph Waldo Emerson famously called “the shot heard ’round the world.” But Paul Revere never reached Concord — he was stopped and captured by British forces in neighboring Lincoln, and it was his fellow midnight rider Samuel Prescott who instead made it to the route’s endpoint.

Revere later wrote of meeting Prescott, a 24-year-old physician from Concord, on the road that night: “I knew right away he was a true Son of Liberty!” And indeed, there were multiple such dedicated revolutionaries who helped organize and take part in these pre-battle midnight rides alongside Revere and Prescott. At the time that Revere met Prescott, he was riding with William Dawes, a local tanner. Like Revere, Dawes had been dispatched by the president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, Dr. Joseph Warren, to warn local towns and leaders of the incipient British attack. Both Dawes and Warren would fight two months later in the June 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill; Warren’s death there would become a crucial rallying cry for the colonists in this first Revolutionary year.

Like Revere, Dawes didn’t make it as far as Concord that night, as he was thrown from his horse during the same encounter with British troops and walked home. Once Prescott did arrive in Concord, members of the Provincial Congress in the town supposedly dispatched additional riders from there to warn other neighboring towns. The identities of those subsequent riders are even less well-remembered than those of Prescott and Dawes, a telling statement on the power of Longfellow’s poem and the collective myth-making around Revere.

But while each of those figures was risking a great deal by taking part in the midnight ride, the larger and even more accurate historical point is that this influential Revolutionary event wasn’t defined by individual riders at all — certainly not just Revere, but really not any of them as individual participants. It was a collective action, one well-organized by the colonists’ new provincial government and featuring riders across multiple moments and throughout the region. It makes sense that Longfellow would focus his poem on one representative individual, and one with a name that rhymes with “hear” at that. But using that poem as an educational text risks not only minimizing the actions of all of Revere’s compatriots, but also portraying these Revolutionary events as the product of mythic individual figures, rather than part of a collective, communal resistance that extended to the political, civic, and military realms.

Moreover, Longfellow’s publication of “Paul Revere’s Ride” nearly 80 years after the end of the Revolutionary War was its own expression of political and civic resistance. Longfellow visited Boston’s Old North Church in April 1860 and began writing the poem shortly thereafter, but his decision to publish it later in the year was influenced by far more overarching current events. Perhaps the most consistent theme across Longfellow’s long, varied, and hugely successful literary career was his ardent abolitionism — he was best friends with the radical abolitionist Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner and dedicated his early collection Poems on Slavery (1842) to that cause. Longfellow was frustrated by the deepening crisis around slavery, which he saw as a betrayal of the Revolution’s legacies and ideals, and it was far from coincidental that “Paul Revere’s Ride” appeared in an Atlantic Monthly issue published on December 20, 1860, the same day that South Carolina became the first state to vote to secede.

Reading Longfellow’s poem with that context in mind can significantly shift our interpretation of its closing lines in particular:

For, borne on the night-wind of the Past,

Through all our history, to the last,

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.

1860 was an hour of darkness and peril and need indeed, one just as fraught as the Revolution’s early moments. Longfellow knew that his poem was an act of national myth-making, but he hoped that the people would listen and hear it, that his stirring poetic reminder of Revolutionary bravery and ideals would produce its own collective resistance in a moment that required nothing less.

Teaching and learning American history is its own challenging and brave act, in April 2022 more than ever. It requires pushing past simplifying myths to engage with the layers of history that truly define our national story. The longstanding prominence of “Paul Revere’s Ride” includes some simplifications to be sure — but Longfellow’s poem can also serve as a starting point for a more full, accurate, and ultimately inspiring historical education.

Featured image: “Midnight Ride of Paul Revere,” (detail) by Grant Wood, 1931 (Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now