It was a cold day just before New Year’s Eve 2018, and I was in Rosenberg, Texas, about 14 miles outside Houston. I was inside a ramshackle barn in a half-covered riding ring. A dozen black-mouth curs, cow dogs, lounged in wire kennels beside the arena. They bayed at the sight of the man on the horse; they knew a cowboy when they saw one and keened their wish to be out with him, punching cattle.

Larry Callies, the cowboy, was exercising a big bay before an audience of the dogs and a pen of yearling steer who were rubbing their horns idly on the fencing. I watched too, alongside the little longhorns, as I sat on a chestnut quarter horse named Bud. Callies was in the market for a new ride, and we had driven out to this ranch on the outskirts of Rosenberg to test-drive a chunky gelding named Swamper.

With a swish, Callies loped into a corner of the ring and rocked his mount back on its haunches just by a flick of his wrist. The animal stopped expertly, dead square, then spun on a dime. The dogs yelped. Even the calves seemed impressed.

Swamper was not a looker, a fact Callies had been loudly reminding the horse about all morning. The gelding had two beady eyes gone smoky under a film of cataract and a swayback that begged for a saddle to hide it. But he was pretty spry for any horse, much less one who was pushing 22 years old.

“I’m going to offer half for this horse,” Callies said conspiratorially to me as he rode Swamper alongside Bud, looking around to be sure he was out of earshot of the rancher who was selling Swamper. But there wasn’t much chance Callies could be heard: His voice has creaked like a barn door ever since the ’90s, when the cowboy’s vocal cords mysteriously decided to stop working. The malady derailed a burgeoning career as a country music crooner. Callies became a postman. “It is a fate about which Mr. Callies is relentlessly upbeat,” I wrote in an article about him in The New York Times, “smiling his wide newscaster smile as he explains that if he had ended up a country music star, he would have had less time for his true passion: rodeo.”

I leaned out of the saddle and stage-whispered back: “So you like him, then? Even though you can’t stop saying in front of the poor thing how ugly he is?” I said, “You know, Swamper has ears, Larry.”

“I don’t like him,” Callies said, the rust rattling in his throat. He pulled off his dark felt cowboy hat and pressed it to the side of his face so it shielded his mouth from any eavesdroppers, steer or human. “I love him. I could rope any steer in Texas off the back of this here Swamper. But don’t you dare breathe a word about it. I’m trying to get him for half-price!”

In his rodeo shirt, Wrangler jeans, spit-shined boots, and black felt Stetson, Callies, then age 65, groomed Swamper beside me, every inch the cowboy. In case you missed the memo, the bumper sticker on the pickup we drove there said “Gone Roping,” and the flatbed was full of nothing but rawhide and lassos. Callies was a cowboy to the caterwauling cow dogs, and pure cowboy in the saddle, implacable as the old but catty Swamper had jigged and zagged around the ranch, Callies’s brow furrowed in concentration, feeling the animal out.

“But not everyone sees a cowboy when they look at Mr. Callies,” my Times article continued. “Racism and history’s omissions have meant that for many, he’s miscast: Mr. Callies is Black.”

Historians and Hollywood have erased Black cowboys from their rightful place among the sunset and sagebrush and the Western vistas of our minds. Prejudice to this day has continued to finish the job, painting all-white portraits of the American frontier. In fact, one in four cowboys on the frontier were Black, according to data and historical accounts from the pioneer era, which began in 1865 after the Civil War and ended in about 1895. Yet their legacy has been whitewashed from Western iconography and American lore by John Wayne and Sergio Leone and written in invisible ink in the pages of the Lone Ranger comic books.

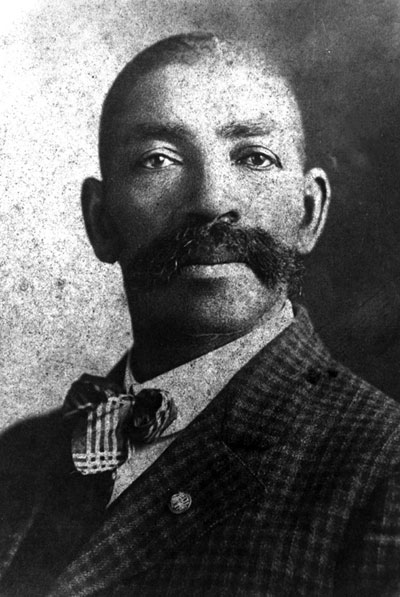

It is an ugly omission, theirs a true story that society has long neglected to tell, bias and bigotry putting only white skin under silver-screen Stetsons. Blacks were lawmen meting out frontier justice, like Bass Reeves, an Arkansas man who self-emancipated from enslavement and was commissioned as a U.S. deputy marshal in 1875. (Some believe Reeves was the inspiration for the Lone Ranger himself.) They were cowboys who were as famous in their time as Roy Rogers, such as Bill Pickett, the inventor of the rodeo sport of bulldogging, rassling a calf to the ground with bare hands. Though he was born in 1870, he was inducted into the Pro Rodeo Hall of Fame only in 1989. He was its first Black honoree.

And Blacks were outlaws too, as notorious in their day as Billy the Kid, like Cherokee Bill, who used his race as an asset for the gangs he joined: His skin meant free passage through native-controlled territories forbidden to white renegades and staying one step ahead of the law. But I bet you’ve only ever heard of one of those Bills.

Some believe that the word cowboy itself points to the blackness of those who bore the label. First recorded in the English language in the early 1700s, initially it referred to actual boys, that is, kids who tend to cows. By the 1800s, the definition had changed to the term we know today. And yet during that same era, boy was often a pejorative reserved for Blacks.

I was in Rosenberg that day searching not for horses but for the Black cowboy’s story. I found it tucked inside a former barbershop at the edge of town. Today it is a tiny storefront museum that Callies spent his life savings to found: the Black Cowboy Museum. He opened it in 2017, his shrine to cowboys who are enshrined few places else.

Until he was an adult, Callies didn’t know what role people who looked like him played in the country’s story, no conception of the Black cowboys’ rich legacy. Then on a rainy afternoon nearly 20 years ago, he was clearing out a cluttered tack room at a guest ranch where he was employed as a cowboy, when he came across a photo on its way to the trash. It was from the 1880s and showed eight cowboys and eight horses.

Seven of the cowboys were Black.

Looking into those faces, he saw faces like his own for the first time as part of the narrative of America’s invention. In the Black cowboy’s erasure from the story of the West, Callies saw his family’s own marginalization from the annals of cowboydom.

He counts among his extended family some of the most talented bareback bronc riders and calf ropers in the state’s history. But few of their names are etched into any rodeo buckles or lauded in rodeo halls of fame. Until the 1970s, most modern rodeos were segregated. Blacks rode in rodeos of their own, where whites were able to compete, but the same was not true vice versa. Unable to saddle up in sanctioned events, Blacks had no shot at state titles, championships, and official cowboy glory.

That antique photo of the seven black men greeted me as I entered the lobby of his storefront museum, where Callies welcomed me that same day we tried Swamper, turning from postman to docent as we crossed the threshold. Callies opened his museum to stake his claim to his heritage. He had had enough of people doubting who he truly is: the son of a cowboy, who is the son of a cowboy, who is the son of a cowboy.

“I used to go to school and people would kick me if I had a pair of cowboy boots on,” he told me as we wandered the museum, a motley collection of old saddles and rusty six-shooters. As a little dude in El Campo, Texas, in the 1960s, he grew up learning roping from his father at the family’s ranch in a still-segregated town and country. “I had to quit wearing them because they would beat me up. Whites would beat me, told me the boots were not my own. Blacks would beat me, told me I was a Black guy who wants to be white.”

Callies’s sandpaper voice crackled, this time not from the affliction of his vocal cords but from the pain of the memories.

“This is who I am. I was always going to be a cowboy. If God made me white, I was going to be a cowboy. But God made me Black. And I am a Black cowboy.”

The museum tour complete, Callies and I pulled up folding chairs inside his little gallery and talked horses, swapping phone pictures of our favorites. Beside us was a display of posters from novelty films he had collected, like 1925’s Chocolate Cowboy, where the star was a white man in blackface. In Harlem on the Prairie, the Black cowboys themselves were viewed as the punch line. In a 1937 review of the film in Time, the reviewer is incredulous at any blackness in the West: “In this apocalyptic land everybody — the prospectors and stagecoach drivers, the medicine men, outlaws, sheriff, the hero with the silver-plated stock saddle — is a gentleman of color. No attempt is made to explain how so much pigment got all over the open spaces. In Negro theatres it will be a conventional Western, and it can play the artier white houses as a parody.”

On a far wall, leather chaps embellished with red hearts were carefully displayed in a vitrine. They belonged to Callies’s cousin Tex Williams, who, Callies believes, was the first Black man to make it to the National High School Rodeo Finals. Light-skinned, Tex slipped in among the teenaged competitors that day in 1967. The stallion launched from the chute with the force of a dust storm, and Tex sat every whipsawing buck on that raging bronco, Callies recalled. The stadium erupted in cheers — for exactly three seconds. That’s when the horse bucked Tex’s cowboy hat clean off, revealing what Callies described as his cousin’s “nappy hair.”

“They booed,” Callies recalled. “They booed as he rode that winning ride.”

Next to the photos of Tex on his many electric rides and the other exhibits, I noticed that in place of any scholarly museum plaques were haphazard magazine clippings explaining the Black cowboy’s place in the world or articles printed off the internet. The whole place felt less like a gallery and more like a family’s -attic — here an uncle’s old spurs, there a cousin’s collection of his trophy buckles — festooned with pictures of relatives yellowed with time.

But I couldn’t begrudge the little museum its lack of rigor. Callies is a mailman, not a historian; a cowboy, not a curator. He had taken his history into his own hands. And just as Swamper was an overlooked horse in which Callies could see his beauty, here was an overlooked story that Callies was demanding the world see too.

“I didn’t want these cowboys to have lived in vain,” Callies said, pointing to the antique photo of the seven Black men who had started it all. He swung out his arm to take in the family albums that filled the museum walls, of cowboys he loved kept out of the rodeo arenas and halls of fame in which he believed they belonged. As more people heard about his mission, they came to him with saddles and spurs, etchings and daguerreotypes of Black cowboys to donate to his collection.

“This is why I opened this museum. Black cowboys meant something,” Callies said. “And they meant something to me.”

Sarah Maslin Nir is a New York Times reporter and Pulitzer Prize finalist who began riding horses when she was just two years old and hasn’t stopped since.

This article is featured in the May/June 2022 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

thank you for your research Mr. Dick Spolyar, it is so upsetting that the Conservatives or trying to erase all the tools that can help everyone learn about the American History

4real have a blessed day

Thank you Mr. Callie for your wonderful black cowboy history!

I never known the contribution that blacks made to the early West!

God bless

Dick Spolyar

The intentional exclusion of Black cowboys from the history books, films and more that persist to this day is wrong on every level. It’s upsetting and disturbing to read what Mr. Callies had to endure, but he’s never let it get in his way, or defeat him. Change comes slowly, but is coming.

I hope in the coming years more quality documentaries will be made on Black cowboys, making the truth known on a mass scale. Larry, if you read this, I’m very proud of you, what you’ve done and continue to do. Keep up the great work. On a side note, I’m no cowboy, but love horses and spending time with them when I can also. Without question one of God’s greatest creations, bar none.

Building Callies museum into a tourist attraction would be a great project for “Black Lives Matter.”