This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

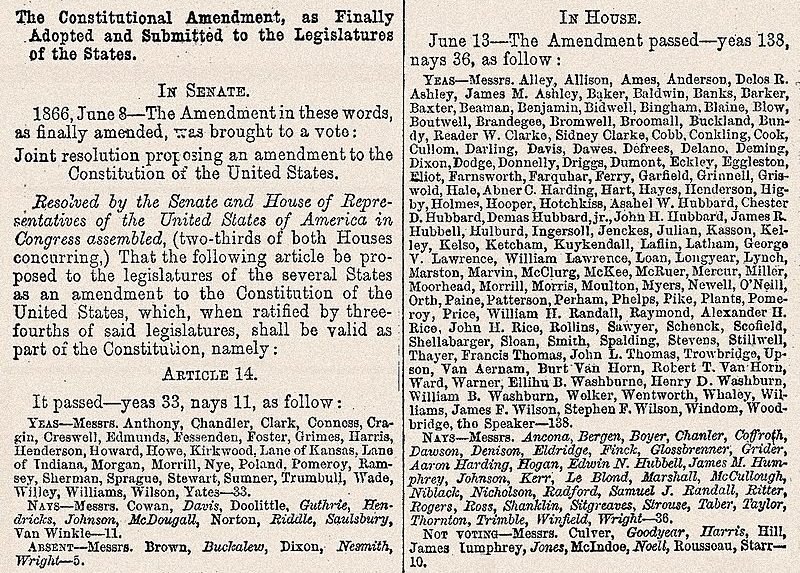

On July 28th, 1868, the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, which granted citizenship to everyone born or naturalized in the United States and guaranteed “equal protection of the laws,” was finally ratified. The ratification process had been far longer and more controversial than for any other amendment — Congress had passed the Reconstruction-era Amendment and Secretary of State William Seward transmitted it to the states for ratification in June 1866, but both legislatures in former Confederate states and Democratic legislators throughout the nation balked at voting for it. Over the next two years bitter fights took place in virtually every legislature, with former Confederate states forced by the Reconstruction Act of 1867 to ratify the Amendment before “said State shall be declared entitled to representation in Congress.” It was only with Georgia’s ratification in late July 1868 that Secretary Seward officially proclaimed on July 28th that the 14th Amendment had been adopted.

Of the 14th Amendment’s five sections, perhaps the most striking is also the briefest: Section 5, which reads simply, “The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” It is of course always the case that every part of the Constitution, including the amendments, requires Congressional action and laws for its enforcement. It is the phrase “by appropriate legislation” that truly stands out in this section, because it suggests that the Amendment’s drafters recognized that the disputes over the 14th Amendment would not end with its ratification.

And indeed, over the next few decades, the Supreme Court would intervene on a number of occasions to help determine not only what constitutes “appropriate legislation” but the very meanings of the Amendment’s core ideas, controversial and influential rulings that echo down into our own moment and its hotly contested Supreme Court decisions.

Precisely 20 and 30 years after the Amendment’s passage through Congress, the Court rendered decisions that reinterpreted the core concept of “equal protection under the law” in striking and troubling ways. The first, 1886’s Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad, was particularly problematic because the most influential portion of the decision was found in a “headnote” not officially part of the decision’s text. The Court’s decision itself was a relatively innocuous intervention in the case’s specific questions, such as whether fences adjoining railroad tracks are considered part of the tracks for the purposes of taxation. But that preceding headnote, a statement attributed to Chief Justice Morrison Waite and transcribed by court reporter J.C. Bancroft Davis (a former railroad company president), reads, “the Court does not wish to hear argument on the question whether the provision in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution which forbids a state to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws applies to these corporations. We are all of opinion that it does.”

Such a headnote should not have held any legal standing or precedent. But by all accounts and all available evidence this informal opinion — that corporations were the equivalent of people under the 14th Amendment’s groundbreaking “equal protection” clause — became far more impactful than anything in the decision’s formal text. It’s far from coincidental that this notion of corporate personhood and Constitutional rights was developed as the nation moved into the depths of the Gilded Age, a late 19th century period increasingly dominated by powerful corporate interests that would only become more entrenched in the 20th century. And even now, this vision of corporations as the equivalent of individual people has influenced decisions such as Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010), which granted even more political power to the nation’s largest and wealthiest corporations and interests.

Extending the equal protection clause to corporate interests was already a striking reinterpretation of the 14th Amendment (which specifically refers to “persons” as protected by this clause). But a decade later, in 1896’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision, the Supreme Court even more radically and destructively reinterpreted this clause. Homer Plessy was a multiracial Louisiana man who had been forced to ride in a “Colored” train car under that state’s laws and system of Jim Crow segregation, and who took his case challenging such racial segregation as unconstitutional all the way to the Supreme Court (with the help of his lawyer, one of the most impressive late 19th century American Renaissance Men, Albion Tourgée). But the Court disagreed, ruling that “in the nature of things [the 14th Amendment] could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to enforce social, as distinguished from political, equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either.”

While Plessy is usually associated with the concept of “separate but equal,” I would argue that it is the difference between “social” and “political” equality that has particularly echoed throughout the century and a quarter after this destructive decision. It was this distinction that made it possible for schools, public spaces, businesses, and so many arenas of American life to segregate legally for so long. And even after the Supreme Court ruled that such racial segregation was unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), this view of the 14th Amendment — that it protects political but not social equality under the law — has made possible continued arguments that (for example) communities like women or LGBTQ Americans are not guaranteed the same civil rights as other Americans, including the right to marry or the right to make their own medical decisions. Many of our current debates depend precisely on how we interpret — or, perhaps more crucially, how the Court interprets — “equal protection under the law.”

In at least one important arena, however, the late 19th century Supreme Court affirmed and amplified the 14th Amendment’s extension of civil rights to all Americans. The Amendment’s Citizenship Clause reads, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof [a reference to the children of foreign diplomats, who are not under U.S. jurisdiction], are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” That would seem to be straightforward enough, a clear assertion of the core concept of birthright citizenship as applying to all children born in the U.S. But over the next decade-and-a-half, Congress passed a number of laws making it impossible for Asian-born immigrants to naturalize as citizens in the United States, leading to lingering questions of whether the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of birthright citizenship extended to Asian American children born in the U.S.

In a critical 1898 decision, the Supreme Court affirmed that it did so extend. In a series of 1880s court cases, young Asian Americans and their families and allies challenged their detention and exclusion under those anti-Asian immigration laws and argued successfully for their status as birthright citizens of the United States. When the case of San Francisco-born cook Wong Kim Ark reached the Supreme Court in March 1897, the U.S. Solicitor General (a former Confederate officer named Holmes Conrad) argued that under laws like the Chinese Exclusion Act, Asian Americans like Wong were not included in this Constitutional right. But the Court disagreed, and in the 1898 United States v. Wong Kim Ark decision ruled that Congressional laws “cannot control the Constitution’s meaning, or impair its effect.” No matter what Congress or political movements might do, this decision helped ensure that the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of birthright citizenship would extend to all native-born Americans, as it has throughout the 125 years since. (The Trump administration sought for years to alter the concept of birthright citizenship, unsuccessfully.)

But the series of controversial and influential recent Supreme Court decisions reflects how the 14th Amendment remains open to debate and interpretation, and how every aspect of these Constitutional concepts and rights can be reinterpreted and changed. As 21st century events unfold, it’s vital to understand the history of the Amendment, the Court, and these foundational national debates.

Featured image: From A Handbook of Politics for 1868, Part I Political Manual for 1866, VI – Votes on Proposed Constitutional Amendments. Philp & Solomons, 1868 (Wikimedia Commons)

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now