Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

There are signs that the word spinster is making a comeback. Though in the past it might have been used with a negative connotation, many modern spinsters are embracing spinsterhood.

But long before the word spinster was an epithet, it was a job title.

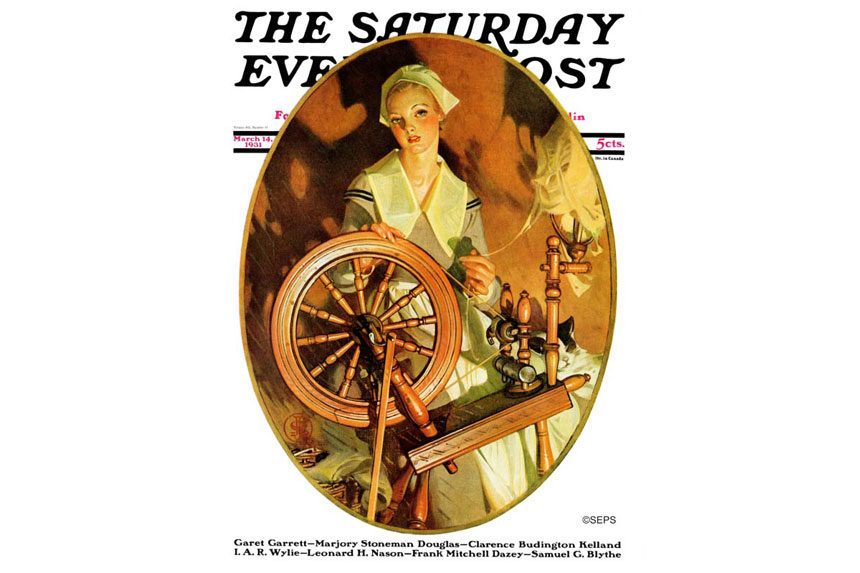

In the mid-14th century, unmarried women who were old enough to work were expected to keep themselves busy during the day. One common job that many women took was spinning fibers into thread, a repetitive but fairly simple job that occupied women’s time and gave them some spending money. Of course, after a woman was married, she no longer needed the job because her husband was expected to provide for her.

So you can see how the word spinster came to be associated with unmarried women. (For what it’s worth, men could be spinsters too, but it was considered “woman’s work.”)

But as technology advanced, innovations in mass production meant that thread spun by hand became less common. The spinster as a job position was slowly becoming obsolete; yet the word spinster hung around, associated with the unmarried women who used to do the job. That association was so strong that by the 17th century, spinster had even become an established legal term for an unmarried woman — completely divorced of its textile origins.

But still, being a spinster was largely considered a temporary state. But, of course, some women stayed unmarried, staying spinsters into their old age — old being a very relative term. By the early 18th century, spinster was used primarily to indicate not just an unmarried woman, but a woman who remained unmarried past the usual age for marriage.

Though spinster may have been used derisively in the past — to be unmarried meant to be unchosen, a socially embarrassing situation — today’s spinsters often wear the title with pride. The modern spinster often enough uses the word to indicate not the lack of a husband but the freedom from the burden of family, the power of self-reliance and self-determination, and the joyful shirking of traditional feminine roles.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

What a delightful feature and 1931 Post cover. I’m glad that she’s depicted doing the job, and is so pretty. I really only knew the word (before now) to mean the typical meaning we associate with it. I appreciate how the Post is my favorite go-to source for continued education; learning something new each day. No tests either, not that I’d mind.