On a rainy morning in May 1917, residents of Boise, Idaho, opened their city’s newspaper to see column after column of World War I dispatches. One report stood out from the rest. It topped page 4, next to the comics, and offered so many explicit details that it couldn’t help but prick the conscience and arouse patriotic conviction.

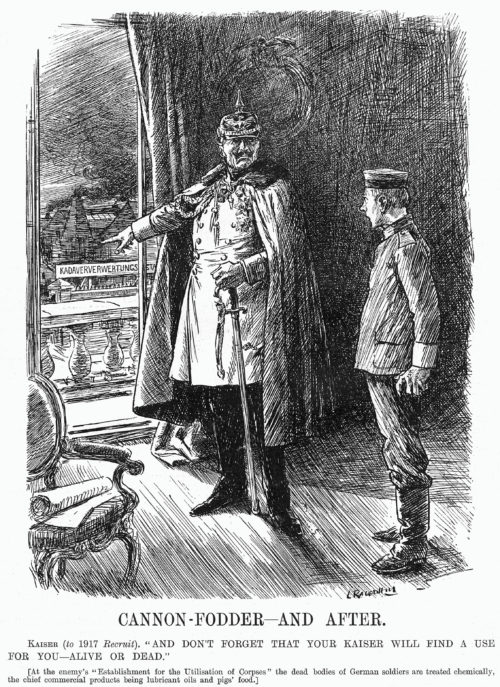

“Now comes the crowning tale of ghoulish horror from the west front in Europe,” reported the Idaho Daily Statesman — “a tale of how the Germans are using the bodies of their dead soldiers for the manufacture of meal, fertilizer, lubricating oil and other more repulsive products.” The article described how the fighters’ corpses were strapped into bundles and transported by rail to a factory hidden by thick forest and surrounded by electric wire. Masked workers in oilskin overalls reportedly handled the bodies with long hooked poles, ushering them toward steaming cauldrons that broke up the fat.

“The report would be incredible,” continued the Statesman, “if it were not given credence by such publications as the London Times, Daily Mail, Paris Temps, Edinburgh Scotsman and many Belgian, French, and Swiss newspapers of standing.”

Americans across the country were reading about the same atrocity. “The story [seems] well authenticated,” reported the Louisville Courier-Journal, which said it was hard to fathom “that a civilized people would treat the corpses of gallant soldiers as a mere commodity.” In North Carolina, the Greensboro Daily News said that, if true, “the German soldier is expected to fight on as usual, in company with the reflection that, today a hero of the Fatherland, tomorrow he may be lubricating oil, soap, and pig feed.”

The story, in modern parlance, had gone viral. It was also completely false. British and Belgian propagandists, along with English newspaper baron Lord Northcliffe, had spun it from improbable eyewitness accounts, an article in a nonexistent Dutch newspaper, and some willful mistranslation. The story contained just enough truth to be plausible: Some German factories recycled dead animals and had the word Kadaver in their name. But when German authorities explained that the word referred to animal carcasses, not human ones, newspapers like the Statesman dismissed that translation as “deliberately untrue.”

More than a century later, viral falsehoods have permeated American life. We’re deluged with deceitful reports: that the Covid-19 vaccine will kill or implant a microchip inside you; that the 2020 election was rigged; that the Sandy Hook and Parkland school shootings were hoaxes and their victims paid actors; that former President Barack Obama was born in Kenya; that Democratic Party leaders ran a sex-trafficking ring out of a Washington, D.C. pizza restaurant. Mistruths provoked the 2021 Capitol Insurrection, which then spawned even more false claims that FBI operatives and Antifa activists had organized the attack.

“We’re in a crescendo of mis- and disinformation,” says Melissa Zimdars, a media studies scholar at Merrimack College in Massachusetts.

The internet has enabled hyperpartisan organizations to reach millions of Americans. Social media amplifies those stories even further.

In this polarized environment, media trust has plunged to one of the lowest points in modern history. According to a 2021 Gallup poll, only 36 percent of U.S. adults said they had a “great deal” or a “fair amount” of trust in mass media to report the news fairly and accurately. That’s a notch higher than in 2016, during the bitter presidential contest between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. But it’s far below the Watergate era, when investigative reporting by The Washington Post and others helped expose a far-reaching political scandal and bring down a president. In 1976, 72 percent of U.S. adults said they trusted the media.

But if false information has reached a crescendo, it’s hardly a new phenomenon. Fake American journalism is older than the country itself and has been shape-shifting for more than three centuries. The German corpse-factory story was one of many manifestations, and a particularly consequential one.

It took until 1925 for the British government to repudiate that World War I story. By then, a former British Army Intelligence chief had admitted that he helped spread the hoax. At a dinner of the National Arts Club in New York, Brigadier General J.V. Charteris recounted how he had come across two German photos during the war: one of dead warriors being transported for burial, and another of dead horses en route to a Kadaver plant. “Knowing how the Chinese revere their ancestors and their dead,” The New York Times reported, Charteris added the horse caption to the soldier photo and sent it to a Shanghai newspaper as an “amusing sidelight.” The Chinese media picked it up, helping propel the war’s most sensational fake-news story.

The damage was anything but a sidelight. According to historians Joachim Neander and Randal Marlin, the Kadaver story might well have reinforced the decision to place harsh conditions on Germany in the Treaty of Versailles. Those conditions, in turn, destabilized the country’s economy and abetted the rise of Hitler. Later, when rumors of Nazi atrocities emerged, Allied leaders viewed them with skepticism. “These mass executions in gas chambers,” wrote Victor Cavendish-Bentinck, chairman of the British Joint Intelligence Committee, in 1943, “remind me of the stories of employment of human corpses during the last war for the manufacture of fat, which was a grotesque lie.”

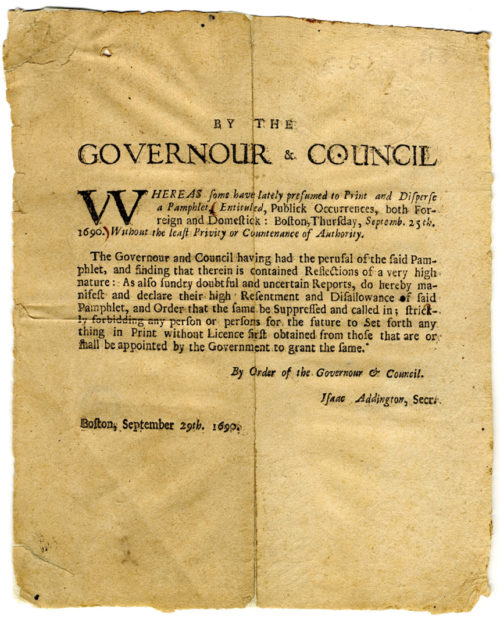

When historian Andie Tucher set out to identify the first American fake-news story, she had a hunch where to look: the inaugural issue of the very first colonial newspaper.

Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick was published in 1690 by Benjamin Harris, a British immigrant living in Boston. Promising an antidote to “the Spirit of Lying,” Harris said he would print only “what we have reason to believe is true, repairing to the best fountains for our Information.” He would correct his errors promptly. And he would expose any “malicious Raiser of a false Report.”

“But he also couldn’t resist,” says Tucher, a professor of journalism at Columbia University. The late 17th century was a period of intense religious struggles in Europe, and Harris was no neutral observer. He was a devout Anabaptist who had served time in an English prison for his anti-Catholic commentary. By the time he moved to Massachusetts and launched Publick Occurrences, Harris knew that Louis XIV, the French monarch, had escalated the persecution of Protestants with the intention of making his country entirely Catholic.

So Harris dropped a salacious tidbit into Issue No. 1. He wrote that Louis’ eldest son was plotting to depose the monarch because of a sexual rivalry. “France is in much trouble (and fear) not only with us but also with his Son,” he wrote, because of reports “that the Father used to lie with the Sons wife.”

This was preposterous, Tucher writes in her new book Not Exactly Lying: Fake News and Fake Journalism in American History. Louis’ daughter-in-law — “known for being devout, multilingual, homely, and ill — had been bedridden for years before her death at the age of twenty-nine.” And Louis, now married to the moralistic Madame de Maintenon, “had long since given up his famously libertine ways.” What’s more, she noted, there’s no historical evidence of an overthrow plot involving the eldest son.

Like today, misinformation was being used to blemish a political opponent, “using stuff that sounds just plausible enough to be true,” says Tucher. “Many people at that point had heard that the king had a reputation for lecherous behavior.” Harris pushed the popular knowledge “a little farther, to make a story that’s really ugly.” So ugly, in fact, that authorities shut down Publick Occurrences after just one issue.

The most famous early American publisher, of course, was Benjamin Franklin, who took a righteous stand for truth in his 1791 autobiography. “In the conduct of my newspaper,” he wrote, “I carefully excluded all libelling, which is of late years become so disgraceful to our country.” But that didn’t stop him from publishing hoaxes that some readers interpreted as fact, says Pennsylvania State University English professor Carla Mulford.

In 1730 — almost four decades after the witch trials ended in Salem, Massachusetts — Franklin concocted another witch trial, this time in Mount Holly, New Jersey. “It seems the Accused had been charged with making their Neighbours Sheep dance in an uncommon manner,” he wrote in The Pennsylvania Gazette, “and with causing Hogs to speak, and sing Psalms.” In Franklin’s telling, one of the defendants was placed on a scale and weighed against a giant Bible, “but to the great Surprize of the Spectators, Flesh and Bones came down plump, and outweighed that great good Book by abundance.” There is no historic evidence that any of this took place.

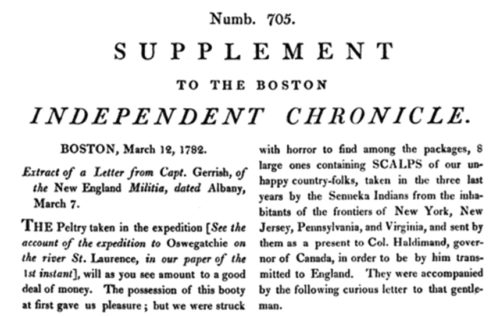

More than a half-century later, during a diplomatic mission to France, Franklin printed a fake supplement to a real Boston newspaper. The pages, complete with ads for local real estate, were designed to look authentic. But the news content was invented.

Franklin’s front-page story, published in 1782, purported to be an inventory of almost 1,000 scalps taken by Native Americans allied with King George III. Eighteen were “marked with a little yellow Flame, to denote their being of Prisoners burnt alive.” Another 29 were “little Infants’ scalps” decorated with black knives “to shew they were ript out of their Mothers’ Bellies.”

At the time, Franklin was negotiating a peace with England after the American Revolution. He hoped this racist hoax would shock the British public and give him leverage as he sought reparations from the former colonizers. “I send enclosed a Paper,” he wrote fellow diplomat John Adams, without betraying his own authorship. “If it were re-publish’d in England it might make them a little asham’d of themselves.”

In the early days of the American nation, newspapers were written for the wealthy. Prices were high and circulation numbers low. This changed in the 1830s with the rise of the “penny press” — cheap newspapers like The Sun in New York, marketed to working-class readers and packed with violence, scandal, and sex. (Not to mention science fiction: The Sun, in 1835, reported the discovery of a lunar civilization with blueish unicorns, two-legged beavers, and temple-dwelling “man-bats.”)

The stories were chosen not for their newsworthiness, but rather for their entertainment value. Unlike 21st-century journalism, with its ethics codes and best practices, 19th-century papers didn’t promise to be trustworthy. Readers instead were invited to what Tucher calls “a spirited public debate” over whether the stories were true. “The penny press was telling this working-class readership: ‘You can figure out anything,’” she says. “‘You have the power. You have the right. You are smart enough to decide.’”

Newspapers went for the lurid — stories of characters like Maria Monk, who supposedly escaped the Hotel Dieu, a Montreal convent she claimed was rife with torture, sexual abuse, and infanticide. In a book published in 1836, Monk said she fled the convent after a priest impregnated her, and eventually landed in New York.

Monk’s story was full of cracks. According to her mother, she was never a nun. And the Hotel Dieu’s interior looked nothing like the place Monk described. Still, the story played into the nativism washing over America — a backlash against the Catholic immigrants arriving from Ireland, Germany, and Austria and a growing fear that the Vatican was scheming to take over America. “Well-respected elite citizens [were] warning against the influences of Rome, and really focusing on the Pope as spearheading this larger, vast conspiracy,” says Cassandra Yacovazzi, a historian at the University of South Florida, Sarasota-Manatee.

The Sun feasted on the tales. It covered Monk’s story extensively, but said the veracity was up to readers to figure out. “We do not, and indeed cannot, vouch for the truth of the appalling disclosures,” the editors wrote. “They may be true or they may be false, they may be partially true, or partially false, and we have no better means than are possessed by every reader to decide.” It took another paper, the Commercial Advertiser, to investigate and debunk Maria Monk’s claims.

The Saturday Evening Post, too, denounced the story as a “mass of lies” steeped in religious bigotry. “What a lesson this is for the public,” the magazine editorialized. “They ought to blush at their conduct — at that credulity — at that gullibility which prepares their pockets for the bait, that is accordingly thrown into them.”

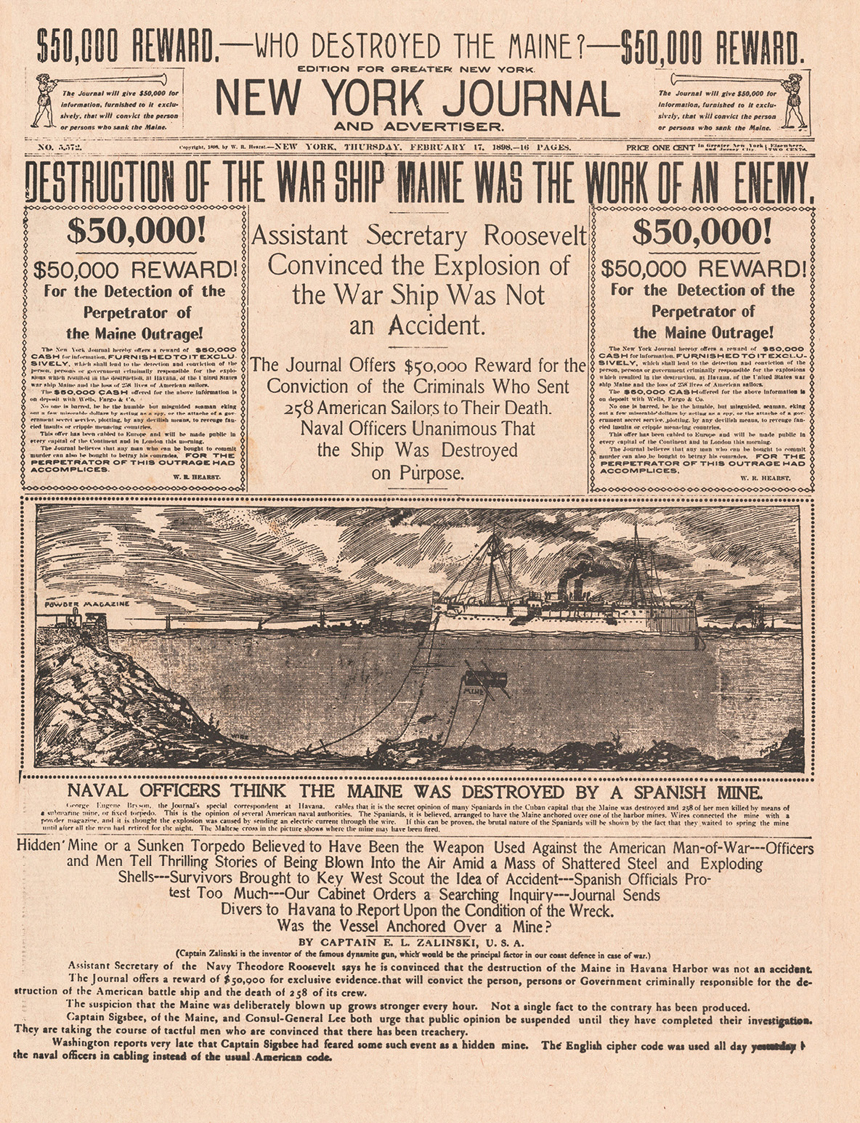

A second wave of sensationalism swept through the end of the 19th century, as cities like New York swelled, electrified, and industrialized. It was called “yellow journalism,” after a cartoon character named The Yellow Kid, and this time the readers included the same immigrants targeted by the Monk story. At the heart of the yellow press were two rival papers, William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal and Joseph Pulitzer’s The World.

Truth, for them, was a secondary concern. “A few months ago, one of the New York yellow journals sent a woman reporter to write up the strike in the cotton mills, and one day telegraphed her to interview the mayor,” wrote Elizabeth Banks, an American journalist who had relocated to London, in 1898. “The young woman replied that she couldn’t find the mayor — he had gone out of town for the day. Back came the answer, ‘Interview him whether you can find him or not, and send copy within two hours!’” A forged statement by the mayor ran the next day, which Banks says “somewhat surprised the honorable gentleman.”

The most outrageous fake story of the era followed the 1898 explosion of the battleship USS Maine in Cuba’s Havana harbor. More than 250 American sailors died in the blast, and the cause was unknown, but that didn’t slow down the headline writers at the Journal and World. Both supported the Cuban revolutionaries fighting for independence from Spain.

“WAR! SURE!” screamed the Journal’s front page. “MAINE DESTROYED BY SPANISH; THIS PROVED ABSOLUTELY BY DISCOVERY OF THE TORPEDO HOLE.” Another headline said, “THE WAR SHIP MAINE WAS SPLIT IN TWO BY AN ENEMY’S SECRET INFERNAL MACHINE!” These false claims helped shape public opinion in the lead-up to the Spanish-American War.

The Journal also published what was likely a fake interview in which Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt called the paper’s reporting “commendable and accurate.” Roosevelt later said that he had declined to speak to the reporter, who had phoned him at his house. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the future president said he would “as soon think of dealing with a mad dog” as give the Journal an interview.

Meanwhile, other editors were trying to stoke a war closer to home, targeting an entire population of U.S. citizens.

After the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, Blacks became evermore involved in American civic life. They built businesses, organized labor unions, ran for elected office and sometimes won. Their early successes infuriated white supremacists, who fought back with brutal violence and often found allies in local editors.

“White-owned newspapers printed the most vile racist headlines,” says DeNeen Brown, an associate professor of journalism at the University of Maryland. “As a result of those headlines and those false reports, many Black people were shot and they were stabbed and they were dismembered. They were burned alive.”

As mob violence swept the country in 1919, the Arkansas Democrat gave front-page coverage to the Delta town of Elaine, where it described “an alleged negro plot to rise against the white people.” According to one article, a security officer responding to a domestic disturbance had been shot and killed. In response, it said, the sheriff “hastily organized” some posses and dispatched them to Elaine, where they encountered 1,000 to 1,500 Black residents carrying high-powered rifles. “The negroes were assembling in large numbers and had begun promiscuous firing on white persons,” it said. “A girl telephone operator, between screams, told an official here, fighting was in progress in the streets.”

That’s not what happened. In reality, a group of Black tenant farmers, many of them World War I veterans, had gathered at a country church to talk about getting a better price for their cotton crop. Their organizing effort threatened white landowners and cotton brokers, and that night a hostile group showed up to disrupt the meeting.

What happened next remains sketchy, but several tenant farmers described being blindsided by gunfire. “I was on the outside of the church when these white men stopped and put the car lights out, then started to shoot into the church,” one of them told the investigative journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett. Black security guards fired back, and in the resulting melee the white officer died.

In the days that followed, vigilantes converged in Elaine and slaughtered at least 200 Black residents, and possibly many more. “Many of the Black farmers ran into the swamp and hid in the thickets,” says Brown. The governor called in federal troops from nearby Camp Pike. “And there are reports that when Black people saw the soldiers coming toward them, they would come out of their hiding places, thinking that the soldiers were coming to save them. And in fact, the soldiers fired on them.”

While the death toll in Elaine was particularly high, newspaper stories that stoked racial terror with misinformation were wearyingly common. Last year, Brown spearheaded a project in which more than 60 student journalists analyzed newspaper archives. They identified sensationalized coverage, victim blaming, and stories that tried to justify racist violence, and shared their findings on a website called Printing Hate. Along with individual stories, the site has a database of complicit papers, which currently number 66.

The 20th century brought a movement to professionalize the American press. Today’s major newspapers are written and edited by trained journalists adhering to industry-wide standards that put truth-telling at the fore. Investigative reporting has held the powerful accountable, whether by uncovering the Watergate break-in, exposing sexual harassment, or revealing secret government surveillance of U.S. citizens.

But even well-intentioned journalists can be too trusting of political leaders eager to peddle misinformation.

On August 4, 1964, sailors aboard the U.S. destroyer Maddox, stationed in the Gulf of Tonkin off the coast of North Vietnam, picked up some unusual radio messages, sonar signals, and radar images. They interpreted these as an enemy attack. This was early in the Vietnam War, and the United States still had a modest presence. But the sailors had reason for alarm: Two nights earlier, a North Vietnamese officer “went off half-cocked and ordered an attack on the Maddox” — a failed one — “without authority from the high command,” says Clemson University historian Edwin Moïse.

There was no incoming assault on August 4. It was a dark, choppy, rainy night, which offered plenty of room for misinterpretation. Still, the Maddox and another destroyer, the Turner Joy, fired for two hours at the phantom target.

News from the Gulf of Tonkin soon reached the White House, followed by a corrective. “When the Navy ships in the morning started to do an after-action review, they couldn’t find any evidence that an attack had actually taken place,” says Daniel Hallin, a communication professor at the University of California, San Diego, and author of The “Uncensored War”: The Media and Vietnam. “Normally, they would expect to be able to find oil slicks if they had hit PT [torpedo] boats, debris, possibly even bodies or survivors. But they couldn’t find any evidence of it. So they cabled back to Washington, and they said, ‘Well, you know, we’re not so sure what happened.’”

President Lyndon Johnson, at the time, was looking for congressional authority to ramp up the U.S. presence in Vietnam. An attack in the Gulf of Tonkin would provide the justification. So administration officials told reporters an unambiguous story of a North Vietnamese assault followed by a limited tit-for-tat response.

The press reported what officials had told them. Beneath a three-tiered headline, The New York Times described “a naval battle in which a number of North Vietnamese PT boats attacked two United States destroyers with torpedoes. Two of the boats were believed to have been sunk. The United States forces suffered no damage.” Reporter Tom Wicker quoted President Johnson, who accused North Vietnam of “open aggression on the high seas.” Wicker added that the administration “seeks no general extension of the guerilla war.”

This, says Hallin, typified the era. “The way journalists reported on foreign policy, it was a very passive form of reporting. For the most part, they relied on U.S. government officials, and they reported what those officials said more or less at face value. They didn’t question it. They just kind of passed it on.” By comparison, he says, the French newspaper Le Monde examined the evidence for an attack and deemed it inconclusive.

Time magazine went even further than The Times in parroting the official line. Over six pages, it described the battle in cinematic detail, as if it had actually happened. “The night glowed eerily with the nightmarish glare of air-dropped flares and boats’ searchlights,” wrote the anonymous author. “Ten enemy torpedoes sizzled through the water. Each time the skippers, tracking the fish by radar, maneuvered to evade them. Gunfire and gun smells and shouts stung the air. Two of the enemy boats went down. Then, at 1:30 a.m., the remaining PTs ended the fight, roared off through the black night to the north.”

Time was a champion of American intervention in Vietnam. “They really saw it as their role not just to report the information, but to lead public opinion,” says Hallin. “And so they were much more creative and active in reworking the news to mobilize people.”

Johnson got what he wanted. Three days after the incident, Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, authorizing the president to take “all necessary measures” in Vietnam. It was the start of the war’s escalation.

Later, the press reported on Vietnam more skeptically, culminating in the 1971 publication of the Pentagon Papers by The Times and others. But some journalists would continue to trust powerful sources — publishing, during the lead-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, inaccurate stories about Saddam Hussein’s possession of chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons. “After September 11, we reverted for a while to this earlier mentality of ‘we have to trust the president and officials in matters of national security,’” says Hallin. “I think the story of the weapons of mass destruction is very, very similar to what happened with Vietnam.”

Every new technology changes our relationship to the news. “The printing press necessitated us to pay attention, to think critically, to actually read an entire argument,” says Rory Smith, research manager at First Draft, a nonprofit that works against media misinformation. Television began to break the news into soundbites and visual tidbits, creating what Smith calls “decontextualized content.”

But TV networks, like newspapers, had (and still have) journalists overseeing their content. These “gatekeepers,” as media scholars call them, are human and sometimes make mistakes. But they also provide a line of defense against patently false news.

“Now with the advent of social media, it’s peak decontextualization,” says Smith. “You have snippets of snippets of snippets that are being shared in very closed or polarized spaces.” There are no journalist-gatekeepers winnowing out misinformation before people see it. And the posts tend to reinforce their viewers’ preexisting views. If you believe the COVID vaccine contains microchips, you’ll find an internet group reaffirming that.

Before Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok, consuming the news and discussing it were two separate experiences. “We’d read the paper or a magazine, and then we would talk to our family or friends or colleagues over lunch,” says Joe Walther, director of the Center for Information Technology and Society at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “It was separated in time, and it was separated in channel.” We would listen to other perspectives, debate the issues, maybe even modify our own views.

Social media platforms have collapsed that experience. Now we gather in virtual silos with like-minded people. We share news, or fake news, selectively, creating what Walther calls “echo chambers.” Most Americans don’t live solely in these chambers, according to studies. But there’s enough self-isolation online to poison our civic debate.

Not all misinformation is equally harmful, because some of it doesn’t spread very far. “Back in the day,” says Syracuse University political scientist Emily Thorson, “if something aired on the evening news, everyone saw it.” By contrast, a video produced by a conspiracy theorist in his basement might reach a few thousand people and then disappear.

The bigger threat, she says, mirrors what happened in earlier eras — with the German corpse factory, Gulf of Tonkin, and Elaine, Arkansas, stories: People in power use the mass media to spread misinformation widely. When idealogues on either extreme of the political spectrum make claims without evidence, that, Thorson says, is when public opinion really shifts.

There’s no single fix, and certainly no easy one in a society that values free speech. Scholars and advocates have offered many ideas, from better literacy education to the breakup of social-media monopolies. But there’s also a job for us as news consumers — something we can do whenever we encounter provocative information.

“Stop. Take a breath,” says Smith. “Think critically about whatever piece of content you’re looking at. See if you’re reacting emotionally. And if you are, take an even bigger pause and think hard before sharing content.”

“We can scapegoat this all day to the tech platforms, and a lot of the issues do emanate from the tech platforms,” Smith adds. “But at the same time, we’re not static entities. If we think we’re rational beings, we have a will, and we have a chance to actually do our part in preventing the flow of misinformation.”

Barry Yeoman is a freelance magazine writer living in Durham, North Carolina. He teaches journalism at Duke University and Wake Forest University.

This article is featured in the July/August 2022 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

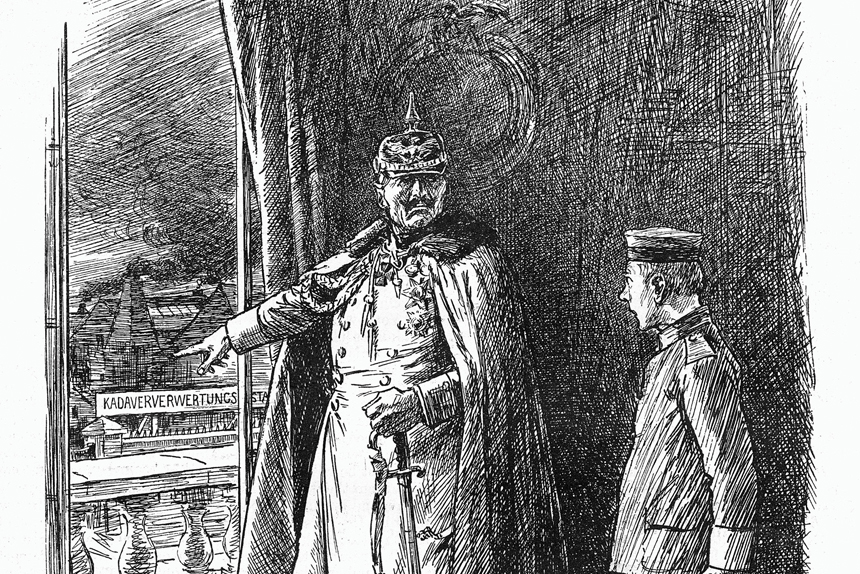

Featured Image: Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you Mr. Yeoman for this article, and The Saturday Evening Post for publishing it. Everything is so polarized across the board now, that’s only getting worse by the day. Fixing the ‘Fake News’ crisis with conventional and social media conglomerates only interested in money and ratings, is proving to be nearly impossible.

The fact that the two major parties are really one big rich party only interested in helping filthy rich Wall Street, military industrial complex (now in a new endless war), richest corporations, isn’t helping. It’s the exact opposite of what the Founding Fathers intended. The fact America’s sadistic “leaders” refer to themselves ONLY as ‘Democrat’ or ‘Republican’ and never ‘American’ is very telling in itself.

No. They use the condescending term ‘the American people’ to refer to all of us they hate and are working against; not even trying to hide it. Fixing that seems as likely as this nation fixing its mass shooting pandemic. If the government could be fixed (total fantasy I know) then it might be easier to go after the media corporations thriving on the dangerous lies of fake news. This nation is sooo mucked up as a direct result of a government only out for themselves setting the tone and example. Where we are is exactly where they want us to be. They’re making billions, so it’s okay! “The American people can die for all we care; in fact we insist on it!”

I appreciate the way the article outlines the flow of how information has been mishandled over the years; that it isn’t just a phenomena of the 21st century – although our information technology makes it far more challenging to deal with news (whether professional or on social platforms). I’d really like the opportunity to refer to what has been offered in my communication classes. Thanks!

As with other articles of such, the Saturday Evening Post would do well to stay out of politics and “fake news reporting.” Your liberal, left wing slant ignores the many times news media edited a clip of one conservative politician or another to achieve their left wing slant. When media outlets like MSNBC, CNN, ABC, NBC, CBS, and others do this they are the creators of the fake news. Instead of editing the clip to get the results they want to achieve why not be HONEST (Let’s face it. These news outlets have forgotten what that word means.) and show an entire, unedited clip. These liberal, left wing news outlets make me sick and Saturday Evening Post, you are right there in bed with them.

Dear Editors:

Its quite interesting, in the picture you selected to illustrate the article on fake news, is fake itself.

The Kaiser had a deformed left hand, and, could _+N O T+_ have held that sword.

Most photos of him show him wearing leather gloves to hide his deformed left hand.

You should be able to find a photo or two of him with the gloves on, or, his left hand in the pocket of

his Army Service uniform great coat.

Sincerely.

Gord Young

Peterborough, ON

You wrote: “but you left out the many, many falsehoods and fake news stories attributed to liberal voices”…Will you provide examples? The author of the article wrote critically about “Yellow Journalism,” and nothing described conflicted with the information I learned about these events when I was in Advanced U.S. History in high school. Even in the mid 60’s students were being taught and urged to “think critically,” to question and to examine ‘NEWS.”

So: if the author provided enough detail and factual information, will you do the same? In other words, Prove your point.

In this interesting article, the author assures us that “Today’s major newspapers are written and edited by trained journalists adhering to industry-wide standards that put truth-telling at the fore.” Of course any article has to be selective – but this one displays some of the very problems encountered in selective media viewpoints and sourcing that raise skepticism. For example, much is made of the Tonkin Gulf incident of August 1964. The August 2 attack on the USS Maddox is undisputed, and even celebrated in a Hanoi war museum. The author dismisses this attack by quoting Edwin Moise’s claim that it was not authorized (which is apparently based on uncorroborated information provided later by representatives of Vietnam’s communist government). The August 4 reports of a second attack are not substantiated, but are treated in a simplistic and almost conspiracy-theory manner as being a major cause of America’s involvement in the Vietnam war. Even if some US media supported the US position to oppose the communist conquest of South Vietnam early in the war (as they had in other wars), the author and his quoted sources ignore the definitive study on later media performance covering the war: “Big Story: How the American Press and Television Reported and Interpreted the Crisis of Tet 1968 in Vietnam and Washington” by Peter Braestrup, the Washington Post’s bureau chief in Saigon and later at the Smithsonian’s Wilson Center for Scholars. In this two-volume 1,498-page study (also available in abridged editions) Braestrup points out “Rarely has contemporary crisis-journalism turned out, in retrospect, to have veered so widely from reality. Essentially, the dominant themes of the words, and film from Vietnam … added up to a portrait of defeat for the allies. Historians, on the contrary, have concluded that the Tet Offensive resulted in a severe military-political setback for Hanoi in the South. To have portrayed such a setback for one side as a defeat for the other – in a major crisis abroad – cannot be counted as a triumph for American journalism.” (A useful book review by Van M. Davidson, Jr. is in the Military Law Review volume 85 (July 1979), pp. 159-68 https://tjaglcs.army.mil/documents/35956/93572/1979-Summer-Aassembled.pdf/0c39c3d8-817a-7340-ae51-7b774b8019db?t=1617218392012&download=true). More facts, more balance, and less reliance on very selective sources and viewpoints, would be a great step forward toward improving the low public confidence in the media.

Your article has an obvious and biased slant. Did this irony escape the author?

And the Post continues its gradual decline.

We would have to have willfully put out our eyes metaphorically if we are to believe that the mainstream news media consists of professionals who labor to bring us the news without bias.

The Social Left is remarkably unaware of itself.

Your opening article lists many possible ‘fake news’ stories, all attributed to conservative voices, but you left out the many, many falsehoods and fake news stories attributed to liberal voices. With a slant that obvious, this article is now considered fake news.

The article puports to suggest that today’s media is a disinterested purveyor of different points of view. Hardly. The New York Times is a prime example of the denigration of journalism to the point that it should be dismissed out of hand. Let’s take one example that recently occurred. An attempt was made on the life of Associate Justice Kavanaugh. The New York Times put this on page 24 of its next addition. The simple fact is that today’s media do not report the news as much as try to make the news and shape the news to its own ideology. There is no reason to trust the media because the media itself cannot be trusted.

This is an interesting article on a valid topic as important today as well as for historic understanding. But I was disappointed when I read the list of examples given as false news today. I assumed the list would be unbiased and provide many examples from many different groups. But instead you created a list that intended to prove only one certain political party creates fake news today, of course the right or Republican. That surprised me! You did not even mention one of the biggest hoaxes in fake news, the Russia collusion hoax alleged against former President Trump. There are so many valuable ideas in your article, but it also appeared you were talking from your own information “silo.” Still, I enjoyed reading it.