I

John Adkins left work early, locked himself in the bathroom with his laptop, and shifted numbers around in a spreadsheet for two hours with his hair in his fists.

“Tell me what’s wrong,” Kendra said through the door.

He heard Noelle, their eight-month-old, crying in Kendra’s arms.

“You can’t keep me in the dark like this.”

He opened the door. Kendra and Noelle both were red-eyed. John suspected that he looked the same.

“Are we okay?” Kendra said.

“I don’t know.”

“We’ll be okay.”

He nodded. “We’ll do what we gotta do.”

* * *

They found a two-bedroom house for rent in Augustus Valley. John’s commute would be farther, but it would cost them a quarter of what they were paying in Beckley.

“I ran the numbers,” John said. “It can work.”

“Augustus Valley, though?”

He shrugged. “We’ll check it out. Won’t hurt to look.”

The house was old, like most everything in that town. But it was structurally sound, it was clean — well, clean enough — and it had just enough space for the three of them.

“Ain’t so bad, right?” John whispered to Kendra as they drove away. Noelle was asleep in the rear-facing car seat behind them.

Kendra shrugged. “I guess.”

“I mean, look. It’s better than a lot of places in Augustus Valley. Honestly, it’s better than a lot of places in Beckley. And it’s cheap, which we need right now.”

“I know. I just … Maybe it’s shallow of me. You know what people say about that town.”

John nodded.

“There’s something else,” she said. “Something about the house. It just felt … wrong.”

John stared at the yellow lines stringing him along the twisting road. He sighed.

She was right. The house was in decent condition for its age. And the landlord seemed friendly, easy-going, and a little hands-off — the latter quality John appreciated greatly. But there was an unsettling aspect to the place that he couldn’t explain.

“I didn’t want none of this, either. But we’re better off than a lot of folks.” He reached over and squeezed her knee. “We’ll make it a home. You’ll see.”

* * *

Before unpacking fully, John and Kendra inspected the house on their own for the first time, at last without a hovering landlord to obscure close observation.

The ceiling seemed higher than it had on their original tour, as if the house was welcoming the newcomers — or backing off from unwanted company. John flicked his gaze the opposite way.

“You know,” he said, “these old hardwood floors … They’re a bit grimy now, but give them a good mopping, and we can find some way to polish them up maybe. … A lot of potential there. And it’ll look better when it ain’t covered with all of our boxes.”

Kendra nodded and bounced Noelle on her hip. “Maybe we can get a nice rug or something.”

“There you go.”

Trying to distract Kendra from a patch of mold growing on the tiny bathroom’s ceiling, John fiddled with the faucet handles on the clawfoot tub.

“A little loose, but I can tighten these up. And I can find some kind of shower conversion kit. No way we’re taking a full bath every morning.”

“It’s cute, I guess.”

John could tell by her tone that she was trying and failing to stay positive. He put an arm around her and kissed Noelle on the cheek. “Let’s look at the kitchen. I think we need to test out that stove with an omelet or two, what do you think?”

He led them to the kitchen, confidence dropping like he was a disgraced salesman whose wares kept failing as they were presented. He turned the knob to a burner and groaned as the pilot clicked repeatedly without success.

“Hold on,” Kendra said. She handed him the baby, then bent down and blew softly at the clicking burner. Blue fire whooshed to life.

“Where’d you learn that trick?” he said.

Kendra shrugged. “Mom and Dad had a cranky old gas stove for a while. We just always knew to do it.” She pulled a frying pan from one of their boxes on the table and set it on the flame. Then she closed her eyes and turned the stove off. “Crap.”

“Oh, right,” John said. “The eggs. I’ll run and get some.”

“Thanks, honey.”

John handed Noelle off and drove down Main Street looking for a grocery store. It didn’t take long before he went by a place not much bigger than their house, the sign admitting its name almost apologetically in faded paint: Pop’s Discount Market. Inside, there wasn’t much more than two aisles and a refrigerated section. He grabbed a dozen eggs and some other staples to tide them over until they could get better groceries from somewhere else. He was back to the house within 15 minutes of leaving.

“You won’t believe this place I found,” he said as he carried the groceries inside. “I swear, you could buy every item in the store, put them in this living room, and still have more space than we do with our boxes all over the floor.”

The house was silent, and Kendra wasn’t in the kitchen. He set the bag down on the table.

“Honey?”

Kendra’s muffled voice came from the pantry: “Down here.”

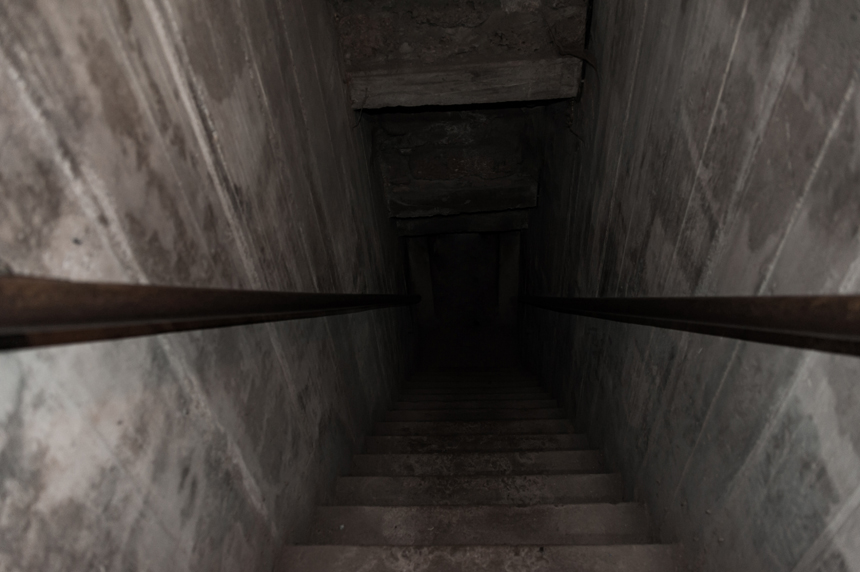

A beam of light shone through the slightly cracked door. John pulled on it and was surprised to see that the light came not from the ceiling, but from below, through an open trapdoor. He scraped both shoulders on the narrow opening and descended gray concrete steps.

The air was cool and moist, and it smelled like a muddy riverbank after the rain. A bulb hung in the center of the cellar; cobwebs caught its light and stretched odd shadows in the corners. Beneath his feet was nothing but packed dirt.

“Kendra, honey?”

She stood statue-like, with her back to him, Noelle in her arms. She stared intently at one corner, but John saw nothing special over her shoulder. Both she and the baby were unnaturally quiet.

John crept toward her cautiously and placed a hand on her back. This contact stirred her enough to speak, though she did not look at him.

“Hi, John,” she said.

He followed her gaze down to where some dirt rose up in a pile against the fieldstone. That’s all it was — a mound of dark, wet dirt — not much to look at. But he stared at it too, and when he spoke, his words seemed far away from him, like a voice heard from underneath a murky pond’s surface.

“Got the eggs.”

“Thanks.”

The three sighed as one.

* * *

John couldn’t say how long they were down there. He couldn’t even remember returning to the kitchen, where they now sat eating scrambled eggs. He almost said something to Kendra, but he was overcome with embarrassment and confusion as to what he meant to ask. He squeezed her hand.

“We’ll be okay,” he said instead.

She nodded and lifted a spoonful of mashed-up boiled eggs to Noelle’s slackened mouth.

* * *

John awoke to hear crying — not from the baby, but from Kendra. He put a hand on her shoulder. She swatted it away.

“What can I do?” he said.

No answer from his wife. He sat on the edge of his mattress and rubbed his temples. The old bedsprings creaked loudly at his slightest movement. His breathing became shaky. He wanted to scream, to cry, to hit something.

Noelle awoke and joined in with her mother. Her lurching squeals quickly escalated to full-on shrieks. John took her from her crib and rocked her in his arms, to no avail. He looked to Kendra for help. She lay on her stomach, propped up on her elbows, her face in her hands, tears and snot streaming onto her pillow.

John took Noelle into the kitchen. She quieted for a moment when he flipped on the light, stunned and squinting, then resumed her wailing with greater gusto.

“Shh,” he whispered as he rocked her. “Daddy’s gonna take care of us. We’re all scared right now. Shh.”

Maybe the baby was hungry. But Kendra didn’t appear to be able to nurse right now, and Pop’s didn’t sell formula. With one hand, he awkwardly filled a saucepan with water and an egg and then set it on the stove to boil.

“Shh. It’s all right, girl. Daddy’s making you some food. Just hold on.”

But Noelle only got louder. Food might quiet her, but it was going to take a while to get the egg boiled, and even longer for it to cool to a safe temperature. John looked around, desperate for ideas. One of Noelle’s pacifiers lay on the kitchen table. He coaxed it into her mouth. She sucked on it for a second, then spit it out and howled. John’s ears throbbed with the sound. It was as if Noelle’s screams were inside him, shaking his innards. He squeezed his eyes shut.

“I’m doing my best,” he said through gritted teeth. “What else can I do?”

He set Noelle down on the table and fled, without thought or aim, to the cellar.

* * *

When he came back up, he found Kendra in a chair nursing the baby. Her face was puffy, her eyes red. His heart dropped, and he turned to the stove in horror.

“It’s all right,” Kendra said. “I turned it off.”

“I’m so sorry,” he said. “I don’t know what …” He collapsed onto the chair across the table from Kendra and started to cry.

“It’s okay,” Kendra whispered. “I took care of it. It’s done.”

“I left her! I left the stove on and just left the baby there!”

“We’re all in this, honey. You can’t bear it all on your own.”

“I don’t even know — why would I go down there? I don’t even remember … Kendra, I can’t remember.”

“Hey, shh … Look. She’s sleeping.”

He looked down at his hands rather than the baby. They were muddy — the cellar floor’s dirt mixed with his tears.

* * *

That week, John bought a piece of plywood cut to the pantry floor’s dimensions. Kendra walked in as he was laying it over the trapdoor. He looked at her dumbly — how could he explain? It just seemed necessary. He feared that if he articulated a reason, he wouldn’t like how it sounded.

She nodded and handed him a box of cast iron skillets. He set it down on the newly covered pantry floor.

II

Kendra crouched to her daughter’s eye level. She could smell the funk of the kindergarten classroom’s old rainbow carpet.

Be a good girl,” she said. “Listen to your teacher and make lots of friends.”

Noelle clung to Kendra and hid her face in her mother’s shoulder.

“Don’t cry, darling. You have to learn how to be a big girl.”

“I don’t want to be a big girl.”

Kendra struggled to hold back her own tears. In the corner of her eye she saw the teacher looking on. Kendra had guessed that this parting would be difficult for them both, but she hadn’t anticipated that her vulnerability would come without privacy. For a moment she felt an irrational hatred for this woman she hadn’t met — this woman who would, until summer, have more influence in Noelle’s life than she. But the malice passed, and shame followed. She consoled herself with the hope that the teacher hadn’t detected these last fleeting emotions.

“Okay,” she said to Noelle. “You don’t have to be a big girl all the way today. Just, maybe… partly-big. Can you go with this nice lady…”

She looked up at the teacher, who had approached and now grinned down at the mother-daughter couple with affected sympathy. “Mrs. Hamrick,” the woman said.

Noelle withdrew her face from Kendra’s arm. A thin tendril of mucus stretched briefly from her nose. She gaped up at the smiling, middle-aged tower that was her new teacher.

“Can you go with Mrs. Hamrick?” Kendra said. “She is very nice and wants to introduce you to all your new friends. Mommy has to go away for just a little while so that you can make new friends like a partly-big girl.”

Noelle’s big blue irises flicked back to Kendra’s. “Partly-big?” She wiped her nose on her sleeve.

“Partly-big. Not even mostly-big.”

Noelle nodded slowly. Mrs. Hamrick’s hand descended, and she took it.

As the teacher led Noelle away, Kendra called out, “Mommy will be back soon to pick you up! I love you!”

But Noelle’s world had just grown much bigger, and she was too overwhelmed to look back.

* * *

Kendra paced the house several times, trying to exorcise her separation anxiety. Kindergarten teachers were trained well enough, right? Mrs. Hamrick probably had more experience with children than Kendra herself.

She sat on the couch and sighed out her tension. The empty house’s stillness suddenly struck her.

When was the last time I’ve been alone?

John usually left his phone in the truck, but she sent him a text anyway:

hey honey hows work?

One of Noelle’s toys — a pink, plush pig that Noelle had named Oinky — stared up at her from the floor as Kendra waited for John’s unlikely reply. Though staring was not quite the word, since Oinky had no eyes. Its gaze seemed to come instead from its orange felt nostrils.

A little unnerved, Kendra stood, walked over to Oinky, and carried the stuffed animal to Noelle’s unmade bed. She stretched the covers smooth and tucked Oinky safely underneath, his snout poking out next to the pillow.

Though Oinky’s security was trivial in the grand scheme of things, the accomplishment soothed Kendra. Then, a revelation: a clean house was no longer a pipe dream. For the first time since becoming pregnant, she could catch up with the everlasting mess — and get ahead of it.

She flipped on a radio and got to work.

* * *

By noon, Kendra could find nothing left to clean in that small house. She poured herself a bowl of cereal and milk. The pseudo-chocolate-flavored puffed rice crackled as invading milk forced air from the grains. This was the loudest sound in the room. Miniature dairy deluges. Kendra giggled, still high from all the finished work.

“Maybe this empty house thing isn’t so bad.”

Her voice sounded louder than she had meant it, accented by the lack of response. Her buzz disappeared. The quiet rushed into her head like the milk that had already turned her cereal to mush.

“Why do we keep buying this crap?” she muttered — more quietly this time, but still unable to bear silence.

She checked her phone. John hadn’t texted back.

She found the number for the school and called.

“Hello, Augustus Valley Elementary-Middle School, how may I help you?”

“May I speak to my daughter?”

“Name and grade?”

“Noelle Adkins; she’s in kindergarten. Mrs. Hamrick is her teacher.”

“And you are?”

She paused, taken aback at the secretary’s disinterested tone and brevity. “Kendra Adkins. I’m Noelle’s mother.”

“Hold, please.”

Kendra’s gaze shifted around the kitchen while she waited — the refrigerator, the stove, the floor — all gleaming now, but likely to be corrupted again this evening. No big deal, though. It would give her something to do tomorrow.

The secretary was taking longer than she had expected. She checked her phone; yes, she was still connected.

Out of a habit she had formed over the last few hours, she mentally toured the house for any place she may have missed in her deep cleaning. As she did this, her eyes were pulled toward the pantry, and something clicked.

She didn’t remember the last time she had swept it out — months? Years? She imagined the layers of dust and crumbs and who knows what else, after all this time, must be —

“Mrs. Adkins?” Mrs. Hamrick’s voice: saccharine, artificially high — but quiet.

“Oh, yes, I’m here. I just wanted to check up on Noelle. May I speak to her?”

“Noelle is doing just fine.” She was almost whispering, but somehow it hurt Kendra’s ears. “I’m afraid she just laid down for her nap with the rest of the kids.”

“I didn’t know they still did nap time in kindergarten.”

“Well, we do it here. You can call back in an hour if you would like, Mrs. Adkins.”

Kendra usually didn’t bend under passive-aggressive pressure, but was suddenly embarrassed as she saw herself turning into a helicopter mom.

“No, that’s fine,” she said. “I’m sure you’ll call me if there are any problems.”

“Of course, Mrs. Adkins. And it is no trouble.”

“Thank you.”

“You’re welcome. Bye-bye, now.”

“Bye.”

She set her phone down on the table and stared at it for a good 30 seconds. Again the silence troubled her — she could almost feel it, like a wind moving through the house, or a fog filling the room.

And there was a musty odor with it, so faint that she thought perhaps it was this extreme stillness that allowed her to notice. Had it always been around? It triggered a maddening sense of déjà vu, but she couldn’t tune in to it enough for a clear memory or idea of what it could be. Perhaps it reminded her of the old carpet in Noelle’s classroom. Perhaps not.

And the smell dared to torment her now — after she had thoroughly cleaned the entire house — ah, but not quite all.

The pantry door was shut, but she envisioned the grime that surely covered that piece of plywood inside. And oh, what might be stewing between that board and the original floor?

That was it. Something must be growing in there. Some kind of mold or mildew.

* * *

Buzzing snapped Kendra out of a daze. Her vibrating phone scuttled across the kitchen table in front of her. She answered it.

“Mrs. Adkins?” it said.

“Yeah?”

“It seems that little Noelle was under the impression that you were picking her up today, so she missed the bus. I’m here in the classroom with her now, but she’s the last child to leave, and she’s quite upset.”

“What? She … what?” Kendra yanked her phone from her ear and peered at its clock. It was 4:30. “I’ll be right there.”

Had she been at the table this whole time? Though she was in a rush, she couldn’t help but glance into the pantry. It was spotless, and everything was meticulously arranged. The plywood was leaned up against the wall. It had, in fact, started cultivating a thick layer of something on the bottom side, and it emanated a sour smell.

So she had cleaned the pantry. She remembered it only vaguely, like a memory from decades back.

As if somehow it could help her bring the time back, she checked her phone. The only clues it gave were two texts from John:

hey baby good now that its lunch

how are u

He had sent them both at 12:58. Her phone indicated that she had read them.

What is going on with me?

She could figure this out later. Noelle was alone — well, alone with her teacher, at least, though that thought made Kendra feel even worse somehow. She ran to her bedroom and snatched her purse from beside her bed. On her way out, she paused, went back to the pantry, and took the gross plywood with her. She left it on the curb for the garbage man to pick up in the morning.

III

Noelle liked the yellow blanket because it was thin enough that she could feel the grass underneath. And the color made it easier for her to keep track of her LEGOs. Well, except for the yellow ones. She used all of those first so that she didn’t lose any.

“What are you building, darling?” Mommy said lazily. She lay on a towel a few feet away. Wearing sunglasses, jeans, and a T-shirt, she was more interested in a nap than a tan.

“A house.”

Houses were Noelle’s specialty. Daddy had even showed her how to layer the edges of the blocks inward until a roof completely covered the four walls. She had figured out for herself how to leave a space open in one wall for the door so that she could look inside when she was done.

“That’s nice. Who lives in the house?”

Noelle straightened. She hadn’t thought of that. But Mommy was right. A house likes to hold things, just like her tummy liked to hold cookies in it.

“The mice, I think.”

“Oh dear.” Mommy laughed. “We better not have mice in our house.”

“Not our house. This one. Our house is too big for mice.”

Kendra chuckled. “Just barely.”

Noelle smiled and resumed construction. The bottom row was yellow. The second row was part yellow, part green. She began on the third row — red and green.

“What do you think about having Mommy as a teacher next year?”

“Does that mean I won’t have Mrs. Hamrick?”

“I’m only going to be a substitute. That’s who comes when a teacher needs a day off. So maybe sometimes your normal teacher will be gone and I’ll be there.”

“That sounds nice.”

Noelle found an extra-long block and pushed it down on one of the walls. She liked the way the long ones sank in and held so firmly.

“You wouldn’t have Mrs. Hamrick anyway. She only teaches kindergarten. You’re going to be in first grade.”

“Oh.” She hadn’t realized that she would have to get a new teacher. “What if my new teacher never wants to take a day off?”

“I’ll be subbing for anybody who asks. Including the big kids’ school. Mommy’s gotta get out of this house more. It gets awful lonely without you and Daddy around. Could use the money, too.”

An ant crawled across the corner of the blanket.

“You just wait, Mr. Ant,” Noelle said. “Soon the house will be done. And if Miss Mouse doesn’t want it, maybe you can live there. Or maybe Miss Mouse would like to marry you. Then you both can have it.”

She pictured Mr. Ant carrying his new mouse bride over the LEGO house’s threshold. At a picnic last weekend, she had watched a string of ants carry away pieces of food much bigger than themselves. She wondered if the ant would be able to carry the whole house away if he wanted. She wished she could be as strong as an ant.

She also wished she had some food, though she didn’t need a big huge meal. Just a little snack.

“Mommy, can I have a cookie?”

“No, honey. Daddy will be home in a couple hours. He’s bringing pizza.”

The ant was gone. He hadn’t even tried to take one LEGO. And she was pretty sure he could have carried more than just one.

“I need to go potty.”

“Well go on, then. You know where it is.”

Noelle ran up the back porch stairs and through the open door.

Without any air conditioning, the house got very stuffy in the summer, though the fans and open windows helped some. But that funny smell was always there, especially when it got very hot. Mommy and Daddy didn’t seem to mind it as much as she did, but if they had been gone for a while, she noticed that they would scrunch up their noses when they walked inside.

She really did have to potty — she wasn’t lying about that. After she finished, she peeked out from the bathroom to see if Mommy could see her from outside. But she couldn’t see. Mommy probably wouldn’t be watching anyway. The sun had made Mommy sleepy.

Noelle tiptoed to the kitchen. She had seen Mommy put the box of cookies in the pantry. She wondered if Mommy put them there so that the good smell of the cookies would fix that funny smell, which seemed to be stronger when that door was open.

She pulled a chair over to the pantry, careful to drag it slowly and quietly. Mommy may have been sleepy a few minutes ago, but she had a knack for walking in on Noelle at times like this.

She pinched her nose and opened the pantry door. Just to see if anything was different, she released her nose and took a quick sniff.

“Ew!”

The cookies were not helping at all. If anything, the cookies were probably going to go bad sooner. It was good that she was taking one, so that it wouldn’t go bad in there. Actually, it might be even better if she took two.

She was about to pull the chair under the shelves when she noticed something strange on the floor. Her curiosity overcame any thoughts of cookies or of funny smells, and she dropped to her hands and knees. Straight cracks in the wood formed a square, with a small metal hinge on one side and a hole the size of Daddy’s finger on the other.

A secret door! Like in a movie!

She wondered why she had never noticed this before — and she was six now, almost six and a half!

She put three fingers in the hole. The door was heavy, but Noelle lifted it with the strength of an ant.

* * *

John felt the pickup’s rear end slip around the curves, but his boot crushed the accelerator to the limit of his ability to control the vehicle. All he could think of was Kendra’s frantic voicemail.

He had run out to his truck, wanting change for a soda to hold him over until the end of work. Before going back in, he had checked his phone and listened to the recording with mounting dread.

He understood less than half of her rushed, panicked words, but he got the most important part of her message: Kendra had accidentally fallen asleep in the yard for 20 minutes or so; when she woke up, Noelle was gone.

John hadn’t even bothered to check with his boss, though there was still 50 minutes left on his shift.

He skidded to a halt in the gravel alongside the house, just behind their beat-up sedan.

“Kendra! Noelle!”

He ran inside, praying that Kendra had found Noelle, though he knew deep down that if all was well, she would have called him again.

The house was dead silent.

“Noelle? Honey?”

If his daughter was still missing, Kendra might have started searching the neighborhood on foot. Noelle had never walked off before, though — but the alternative to her wandering off, that some creep had stolen her, was more than John could bear to imagine.

The sight of the open pantry door stopped him cold. He couldn’t say why it should cause him any more anxiety than Noelle’s disappearance — Kendra had likely left it open in her search. Still, he remained frozen for a minute as a cotton ball grew in his throat.

He finally swallowed down the painful lump and crossed the kitchen floor.

The open trapdoor revealed nothing but an almost solid-looking black square. As he leaned down to shut it, he heard rustling and soft sucking sounds.

He squeezed through the hole and felt his way down the stairs at a torturously slow pace. At last he stood on the packed dirt, blind but certain he wasn’t alone.

“Hello?” he said — he meant to sound calm and forceful, but the word came out in a meek whisper.

He reached up without thinking, and by muscle memory he grasped the short metal pull chain next to the bulb. Light filled the cellar in an instant, and he couldn’t take it back.

His scream came out as a long silent breath.

How?

But he knew how. He remembered now the first time he descended those cold concrete steps alone, the first night in this house. He remembered his frustration, his desperation, his fear, his sweat and tears burning like ice on his face and neck, his heart rate increasing as he ran to the corner and knelt before the small dirt mound. The moist, freezing grit had numbed his hands as he dug a hole with only his fingernails for spades.

He couldn’t remember where the seed had come from, but in his mind’s eye he now saw his fingers pinched around it, hovering over the freshly dug hole, opening — the seed sticking to his thumb for half a second before falling — then his stained hands filling in the hole and patting it down.

And from that inexplicable seed, it had grown: green and brown, a creature of vine and branch with leaves for scales as well as plumage. Voiceless, probably brainless, too — but it felt wrong to say it neither spoke nor thought.

It encompassed both Kendra and Noelle in its bushy foliage. A motherly embrace. They appeared to be sleeping, except that they both sucked sap from woody appendages.

John stepped toward it. He felt as though he had just awakened from a senseless dream, moving of his own free will but unable to comprehend himself. Room was made for him to suckle next to his family.

A fleeting thought: If I run now, I can escape.

Whether or not he truly could, he knew that he wouldn’t leave them. And why should he? See how safe! See how secure!

He crawled inside, and it enclosed him — safe, secure.

Later, they would remember none of this.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Really enjoyed this.

Yipe! That’s a trip into the Night Gallery! Marvelous story!