Helen has understood for a long while now that Vivienne has flipped out, that she is losing her marbles one by one. It’s been a painful thing to witness and sometimes Helen cries over it, but discreetly, so that Viv won’t notice and say, “Now what are you crying about?” Viv is her live-in companion, and her salary is paid by Helen’s sister, who had the good sense to marry a rich man and hang on to him forever. Helen’s husband sold apples on street corners during the Depression and was never quite the same after that, never quite able to recover from the loss of dignity. He lived uneasily for another 25 years and then he fell sick and died, without giving much advance warning.

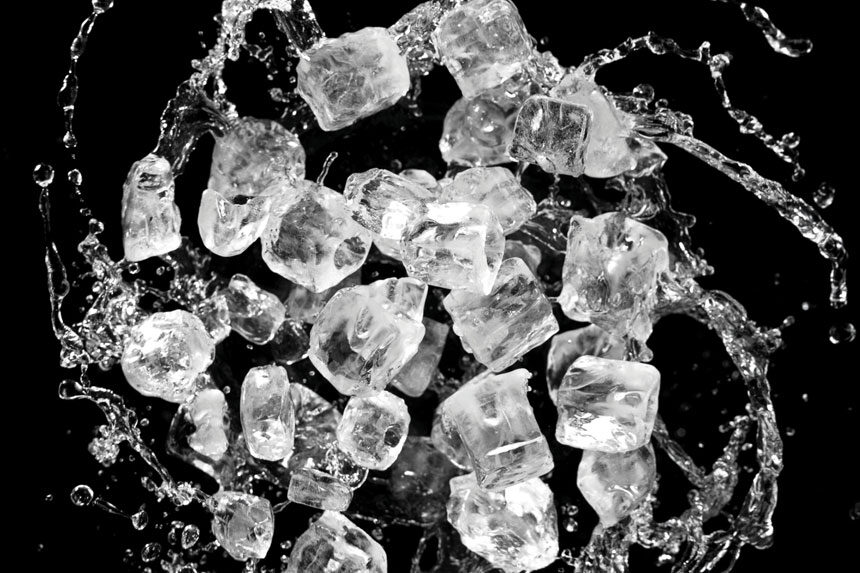

“Cancerous,” Helen says out loud, but Viv ignores her and goes on with what she’s doing, which is hurling handfuls of ice cubes from a five-pound plastic bag to the living-room floor, then smashing the ice with the bottoms of her thick-soled walking shoes. This is to exorcise the smell of evil that Viv claims has permeated the apartment. According to Viv, ice cubes are the only thing that will do the trick. That and the ammonia she has poured all over the lovely parquet flooring.

Watching her, Helen says, “The landlord’s going to have our heads, yours and mine both, I guarantee it.”

“The evil,” Viv says, “is everywhere in this apartment.”

“Don’t you know what all this ammonia is doing to you?” Helen says. “It’s destroying your lungs, that’s what.” She picks herself up from the couch and wanders into the kitchen, where she fixes two bowls of Frosted Mini-Wheats and milk, and adds some sliced banana. She is a small woman with surprisingly long, beautiful legs. Her hair is thick and white, cut short with bangs, like a young girl. (“A pixie cut,” Helen calls it.) She spent most of her life as a bookkeeper and was furious when, long ago, she reached 70 and was forced to give up her job. (“A clear case of antisemitism,” she still insists.)

“This is the Lord’s work I’m doing here!” Viv shouts. “So don’t give me any lectures about lung tissue.”

“Are you too busy doing the Lord’s work to have some dinner?” Helen asks. No response. She flicks on the radio next to her cereal bowl and listens to a call-in show that is hosted by a psychologist with a Ph.D. She loves listening to this show, which makes her feel as if she is right out there in the middle of the world, missing nothing. The caller speaking now is a woman with three grown children — two sons and a daughter. Her sons, the woman says in a trembly voice, are both in prison for selling cocaine, and her daughter, who was clinically depressed from the time she was a teenager, is now in a mental health facility. “It’s a difficult thing,” Helen says. The woman begins to weep as she talks about her children. The psychologist, also a woman, advises the caller that tears are sometimes productive. “Go ahead and cry,” she urges. The caller weeps on the radio for a moment or two longer, and soon there is a click: She has hung up. Helen is crying, too. She thinks of calling the psychologist and saying, “My friend is losing her marbles.” Of course, she’d make an effort to put it a little more delicately: “My friend is so busy doing the Lord’s work that she forgets about eating and doing the grocery shopping. Not to mention the laundry.” Helen looks down at her housecoat. It’s a paisley pattern against a dark background and doesn’t show much dirt. She brings a sleeve up close to her face and sniffs the fabric. “Viv!” she yells. “If cleanliness is next to godliness, I’d advise you to hop to it and get a laundry together.”

Viv appears in the kitchen, tracking slivers of ice onto the linoleum. She is dressed in a short white uniform, white stockings with runs leading straight up from her knees, and white oxfords. Above her breast pocket is a plastic name badge that says “Vivienne.” For years she worked at New York Hospital as a nurse’s aide, until one day she felt too old and cranky for the job and decided to quit. (Or else it was the patients who were too old and cranky; Helen could never remember which.) Viv has four children, all boys, who send her flowers on Mother’s Day — hearts and horseshoes covered with carnations, and once, a single white lily that Viv dumped immediately into the trash. (“The flower of death,” she hissed, as Helen went right into the garbage and retrieved the lily, saying, “Even the flower of death has got to be better than no flowers at all on Mother’s Day.”) The rest of the year, Viv doesn’t hear a peep from any of them. “Once they’ve grown, you can forget it,” she tells Helen. “Children need you like a hole in the head and that’s okay. Anyway, what can you do with four big tall men who get tangled up in your furniture and mess up your house with no regard for how much effort it takes to keep things in order?”

Helen understands. Her daughter, Elizabeth, has lived in Los Angeles for several years now. She complains on the phone every week that it’s a city full of shallow people but at least the weather is good.

“Catch a plane and come visit,” Elizabeth always says. “My treat. And, of course, bring Viv with you.” Helen and Viv find this hilarious. Neither of them has ever been on a plane and they have no interest in risking their necks for a little good weather. Whenever she thinks about it, Helen has to admit that she enjoyed Elizabeth more as a child: all that kissing and hugging and open declarations of love. Still, she wishes she weren’t afraid to travel across the sky like the rest of the world. On bad days, she misses Elizabeth with an ache that settles under her skin and will not budge, like Viv when she mopes in the Barcalounger, contemplating the evil she’s convinced is thriving right under her nose. (“Why here?” Helen wants to know. “What’s so special about this broken-down rat trap, anyway?” But Viv’s not giving any answers.)

Viv sinks down into a seat at the table now and takes Helen’s face in her hands. “Oh, Jesus,” she says, squinting at her. “Jeepers.”

“Eat your cereal,” says Helen. “Notice that there’s some banana in there, plenty of potassium for you.” Viv is smaller than Helen and thin, growing thinner all the time, it seems. Helen worries that one day she’ll slip right out of her uniform and just disappear, leaving behind only a puddle of white.

“You’ve got whiskers growing out of your chin,” Viv announces. “Just like a man.” Her fingers against Helen’s face smell strongly of ammonia; Helen pushes them away.

“Hormones,” says Helen. “Too little of one kind, too much of the other.” She tries to make light of it, but brushing her fingertips over her chin, she feels herself blushing.

“Don’t you move from that table, Miss,” Viv says. Soon Helen hears her making noise in the bathroom, fooling around in the medicine cabinet. Bottles of pills tumble into the sink; something made of metal clatters to the tiled floor.

“Easy there!” Helen yells. “One of these days you’re going to destroy this place altogether. Raze it right to the ground.”

Then Viv is standing over her with a pair of manicure scissors and a small bottle of Mercurochrome. Helen shoves the back of her chair against the wall, covers her face with one arm. “Not today, thanks,” she says.

Smiling, Viv says, “We’ve been together for what, three, four years now, and all of a sudden you’re backing away from me?”

“Seven,” says Helen. “Seven years.”

“Imagine that,” says Viv. “I must have lost track of the time somehow.” Slowly she lowers Helen’s arm from her face, squeezes her hand in a friendly way.

“Somehow,” says Helen, shutting her eyes as Viv comes toward her with the manicure scissors. Then she tells Viv, “You remind me of my mother-in-law. She didn’t care much for me and I didn’t care much for her, and one day she sneaks up behind me and cuts off a piece of my hair just for spite.”

“A deranged woman,” Viv says. She snips cautiously at Helen’s chin. “My poor baby doll,” she says. She dots Helen’s chin with the Mercurochrome, to prevent infection, she says.

“How about a mirror?” says Helen, and immediately changes her mind. “Not a pretty picture, I’m sure,” she says.

“Don’t be so hard on yourself. You’re cute as a button,” Viv says. “For an old lady, anyway.”

“Old old old,” Helen says, tapping a spoon on the edge of her glass cereal bowl. “What’s the point?” Rising and walking to the kitchen window, she rests against the blistered ledge and stares two stories down to the street corner. Lights have just been turned on in the dusk below. It is nearly April now, nearly spring. She watches as some teenagers strip a long black car parked in front of the apartment house: first the hubcaps, front and rear, then the antenna. A radio and two small speaker boxes are next. The thieves are thin boys in their shirtsleeves. Helen raises the window. “Why do you work so hard to make your parents ashamed of you?” she hollers to them.

“How about an Alpine radio, cheap?” one of the boys yells back.

Helen goes to the phone, dials 911, and is put on hold.

Eventually, a woman comes on and takes down the information. She is clearly bored with the details, bored with Helen.

At the end of the conversation she says, “Have a nice day.”

“This neighborhood,” Helen says, rubbing her chin with two fingers. When she takes her hand away, her fingers are bright orange with Mercurochrome.

Viv lights a cigarette and tosses the match into one of the cereal bowls, where it sizzles for an instant, then floats between two slices of banana. She smokes without speaking, leaning one elbow on the table, her head propped against her palm. “There’s nothing wrong with this neighborhood that a few bombs couldn’t cure,” she says finally.

Nodding, Helen says, “I’m going to watch my boyfriends, Mr. MacNeil and Mr. Lehrer, on the television.”

“Boyfriends!” Viv hoots. “Any minute there’s going to be a knock on the door, right, and the delivery boy will be saying, ‘Flowers from MacNeil/Lehrer!’ right?” She laughs in that choked way that Helen doesn’t like, soundlessly, her feet stamping hard under the table.

“Well, at this point, they’re the only boyfriends I’ve got,” Helen says, but she has to laugh at the thought of those flowers arriving and the miniature card tucked inside the miniature envelope that says, “To our sweetie pie.”

“Got any money?” Viv asks when at last she stops laughing.

“You finally decide to do the grocery shopping?”

“Just going out for ice,” says Viv, and Helen is amazed at how utterly ordinary and innocent the words sound, as if she had said, “Just going out for a pack of cigarettes.” It’s the ordinary sound of it that gives Helen a chill, along with Viv’s round eyes, wide-open with alarm.

“What do you see?” Helen asks for the hundredth time.

Not that she expects to get an answer. On the subject of “the evil” (as Helen thinks of it), Viv is resolutely -inarticulate.

Abruptly, Viv shrugs her shoulders and says, “Can I have two dollars?”

Helen breathes through her teeth. The shrug makes her feel desolate, as if Viv were already far away, striding down the block toward the supermarket, a tiny dark madwoman with the moon shining on the shoulders of her hooded corduroy coat. Viv is holding out her hand, palm upward. “Ten dollars, please,” she says patiently.

“Beggar,” says Helen, but not loud enough for Viv to hear. She tears off the month of February from a small calendar perched on top of a low glass-and-wood cabinet. On the back she makes a list: 99% fat free (one qt.) cottage cheese (California style), Hydrox cookies, toothpaste (anything but Crest). “This is an act of faith, Vivienne,” she says, handing her the list and a ten-dollar bill.

“That February was something else,” Viv says. “I must have had to use about 30 pounds of ice, maybe more.” Out into the hallway she goes, hood up around her face, a large pair of men’s canvas work gloves covering her hands. In the living room, Helen turns on the TV, but the tenant in the apartment directly overhead has decided to vacuum.

Helen gets a broom and bangs bravely on the ceiling; all she gets is more static on the TV screen. She shuts off the set and calls her sister Elsie on Sutton Place.

“Oh,” says Elsie, “hello and goodbye. You caught me in the middle of a Great Books night. A few of my lady friends are over and we’re doing Dante’s Inferno.”

“The Inferno?” says Helen, and laughs. “You ought to invite Viv to join your group. That’s right up her alley these days.”

“Vivienne?”

“I’m worried sick, to tell you the truth.”

“Is it money?” Elsie whispers into the phone. “I can write you a check in the morning.”

“She’s destroying my living-room floor,” says Helen, “but that’s the least of it.”

“Do you need wall-to-wall carpeting?” Elsie says. “I’d be glad to send somebody over from Bloomingdale’s —”

“It isn’t that,” Helen interrupts. “It’s something unearthly, I think.”

“Well, I have to hang up now,” her sister says. “You can let me know about the carpeting later.”

Sitting in the Barcalounger, her feet tilted toward the ceiling, hands folded into fists in her lap, Helen says, “Damn.” She remembers the years of her life that were spent at an adding machine, getting things exactly right, making sense of things. Tiresome work, though she has to admit she was good at it. But what does she know of unearthly things? She doesn’t have much patience left. Ice storms in her living room, shards of melting ice everywhere; the sharp, unpleasant scent of ammonia lingering on her skin, her clothes. But in all the world there is only Viv calling her baby doll, cupping her face in her hands, painting her delicately with Mercurochrome. At the end of your life, you’re no fool; you take what is offered. Later, past midnight, long after Viv has come back with her bags of ice, Helen dreams of a carpet of shattered glass spread shimmering over the floor. In her warm bed she shivers, and slides deep under the covers.

Marian Thurm is the author of eight novels — most recently The Blackmailer’s Guide to Love — and five short story collections, including Today Is Not Your Day, a New York Times Editors’ Choice. Her stories have appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Narrative Magazine, Michigan Quarterly Review, and many other magazines and in numerous anthologies, including The Best American Short Stories.

From the Book Pleasure Palace: New and Selected Stories. Copyright © 2021 by Marian Thurm. Reprinted by Permission of Delphinium Books, Inc., Encino, California. All Rights Reserved.

This article appears in the March/April 2023 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

That’s an amazing story.