This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

It has gone largely unnoticed amidst the broader battles over how we teach American history, but this decade represents a frustrating anniversary: the centennial of the first time our federal immigration policies sought to comprehensively limit America’s diversity. Beginning with the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and made even more permanent by the Quota Act of 1924, Congress implemented laws that made it nearly impossible for immigrants to come to the United States from anywhere outside of Western and Northern Europe. (To cite just one example: post-1924, Greece had an annual quota of 100 immigrants to the U.S.) For the next four decades, this nation of immigrants would seek to systemically exclude a significant swath of the world’s migrants from its community.

Those systematic exclusions make it even more important for us to remember America’s defining diversity, to challenge discrimination, and to amplify our multicultural history. Three years ago, I dedicated a National Arab American Heritage Month column to remembering one such multicultural community: Muslim Americans in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Before we close this year’s commemorations, I want to focus on another influential early 20th century Arab American community: New York City’s Little Syria.

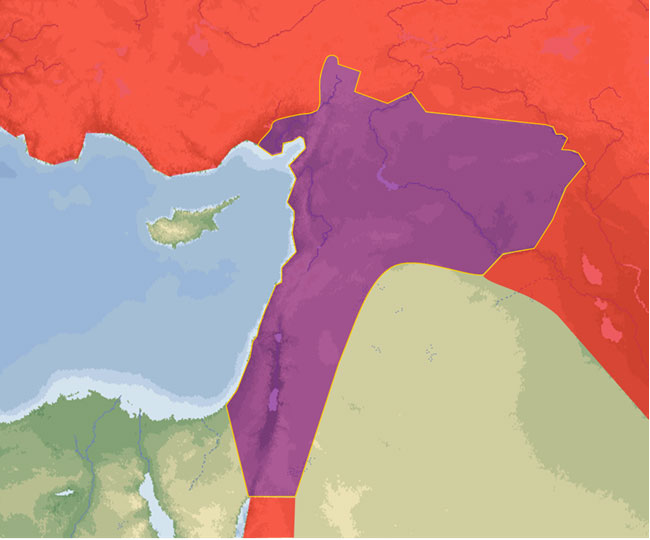

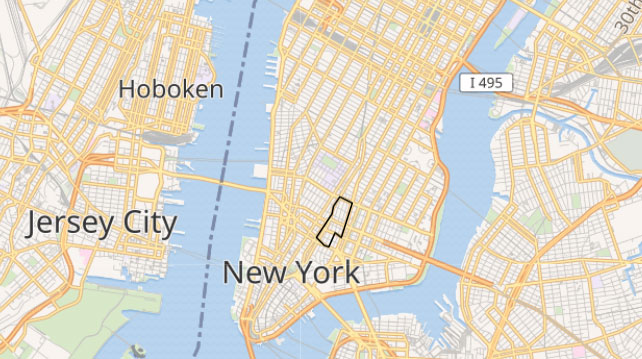

Immigrants from the Middle Eastern region known as Ottoman Syria (which included modern-day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel, and from which those Cedar Rapids arrivals likewise came) began arriving in New York City in significant numbers in the late 19th century. Both fleeing the aftermath of the 1860 Syrian Civil War and pursuing the global economic opportunities created by the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal, these Syrian immigrants belonged to a number of distinct ethnic and religious groups, including no only members of the Druze Islamic community, but also Arab Christians from Ottoman Syria’s Mount Lebanon region. This already diverse immigrant community began to settle in and create a new neighborhood in Lower Manhattan near Battery Park, living in close proximity to the area’s existing Irish, Slavic, and Scandinavian communities yet concentrating sufficiently to lead to the neighborhood’s new nickname of Little Syria (or sometimes, as an 1899 New York Times article termed it, the Syrian Quarter).

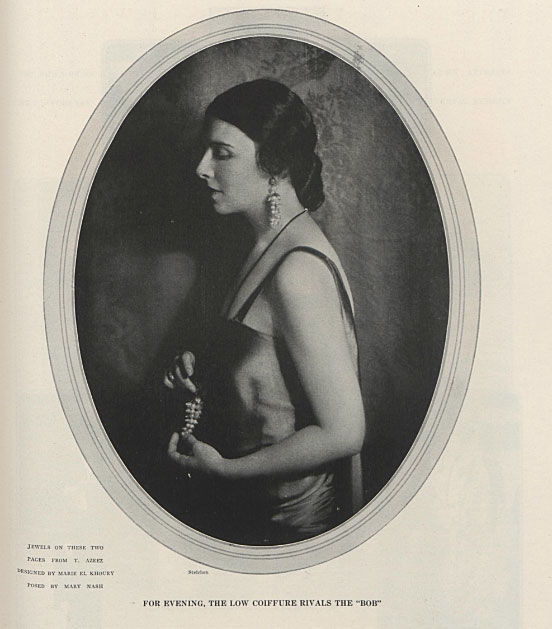

Every member and descendant of that Syrian immigrant community has a unique American story, but here I want to focus on a few inspiring individual examples. Marie Azeez (1883-1957) immigrated to New York from the Mount Lebanon region when she was just 8 years old, arriving in 1891 with her parents and older sister Alice. Her father Tannous Azeez started a successful jewelry business, and with its profits was able to send his very precocious younger daughter to Washington, D.C.’s Washington College for Young Ladies, from which Marie graduated when she was just 17. By that time she was already contributing journalism to a number of Arabic-language periodicals such as al-Da’ira (1900-01), considered the first magazine published in Arabic in the Western Hemisphere. She married that magazine’s publisher Esau el-Khoury in 1902, but when he died in 1904 and her father passed away in 1905 she took over the jewelry business and for the next half-century made it even more successful still (while continuing to write). A 1926 Christian Science Monitor profile called her “a traveler, a poet, a philosopher, [who] into every necklace, bracelet, pendant puts the complexity and subtlety of her own nature.”

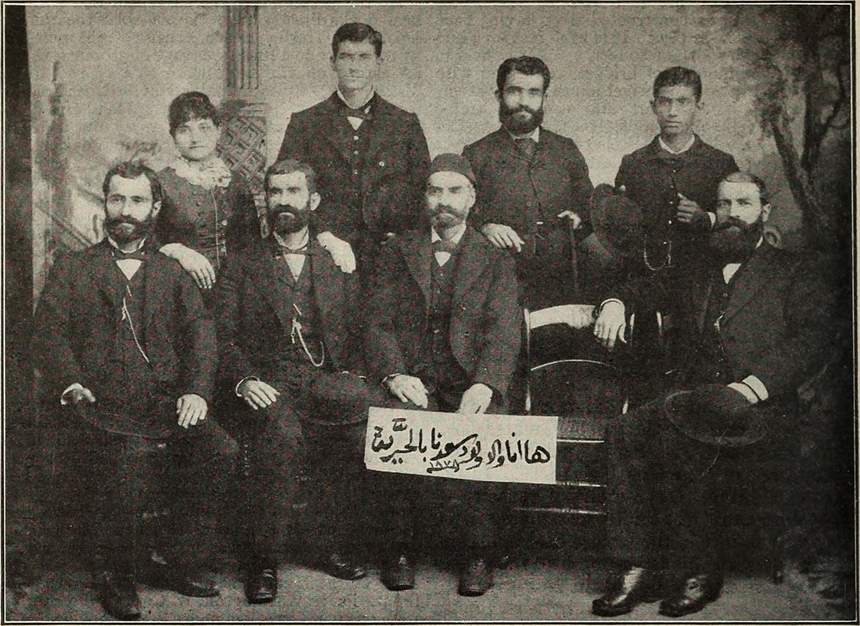

Marie and Esau el-Khoury were just part of a broad and influential journalism community that helped put Little Syria and Arab Americans on the national map. Also published in New York’s Little Syria neighborhood was Kawkab Amirka (Star of America), an Arabic-language newspaper that debuted on April 15, 1892, became a daily paper in 1898, and subsequently appeared daily through 1908. A number of Syrian immigrants contributed to the paper’s founding and operations, including managing editor Najeeb Diab and the brothers Nageeb and Abraham Arbeely. The Arbeely brothers were part of one of the first prominent Syrian American families, arriving in the U.S. as refugees in 1878 and initially settling in Tennessee. Nageeb in particular would become hugely influential, teaching French at Maryville College, serving as President Grover Cleveland’s Consul to Jerusalem in the 1880s, and then working as a government official and lawyer in New York City in the 1890s (where he also founded the Syrian Orthodox Benevolent Society in 1894). It was there that he and Abraham co-founded and funded Kawkab America, which was typeset by hand in its Little Syria office and truly captured that neighborhood’s evolving identity and American voice.

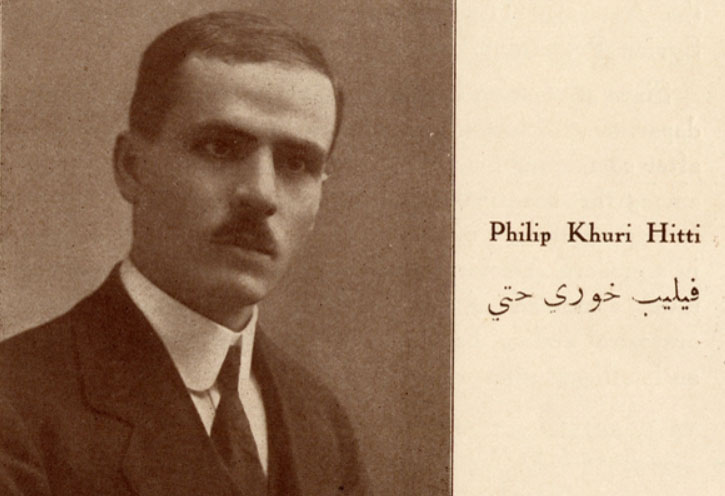

As historian Gregory Shibley has traced at length, Little Syria and the Syrian American community were not immune to the rising xenophobia of late 19th and early 20th century America. New York newspapers including Harper’s Weekly called Syrian street peddlers “dirty Arabs from Mount Lebanon” and warned that “the Syrian Arabs from the Lebanon range have undertaken to invade the United States.” Offering some particularly impassioned and inspiring responses to those prejudices was another of the era’s most impressive Syrian Americans, Professor Philip Khuri Hitti (1886-1978). After a childhood in the Mount Lebanon region and PhD studies at Columbia University, Hitti began his academic career at the American University of Beirut (AUB) before returning to the United States in 1926 to develop and chair a new program in Arabic Studies at Princeton University; over the course of his career he helped create that academic discipline throughout American higher education. Working with allies like historian and journalist Louise Seymour Houghton, with whom he published the four-part 1911 series “Syrians in the United States” while he was still in graduate school, Hitti helped resist these xenophobic narratives and make the case for the longstanding presence and influential legacy of this American community.

Over time, the Little Syria neighborhood in particular dissipated, its inhabitants and families spreading out around the United States. Efforts to commemorate the neighborhood with public memorials remain in progress, and offer one important way to remember this historic community and to celebrate National Arab American Heritage Month.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Any news on or from Dalith?

A really interesting feature, Ben. I wasn’t familiar with it previously. I know out here, there a ‘Little Armenia’ near Hollywood, but other than the sign, nothing. No, the Armenians out here are are mainly in Glendale, and to a lesser extent in nearby Burbank and North Hollywood.

Unfortunately (in general) they’re very clannish and don’t assimilate. I’m aware they’re aware I’m ‘white’, so I make the genuine extra effort to ingratiate myself (it always works) when visiting that Armenian bakery in NH to buy some wonderful Baklava, or dine at the Carousel restaurant in Glendale when over there.