Senior managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

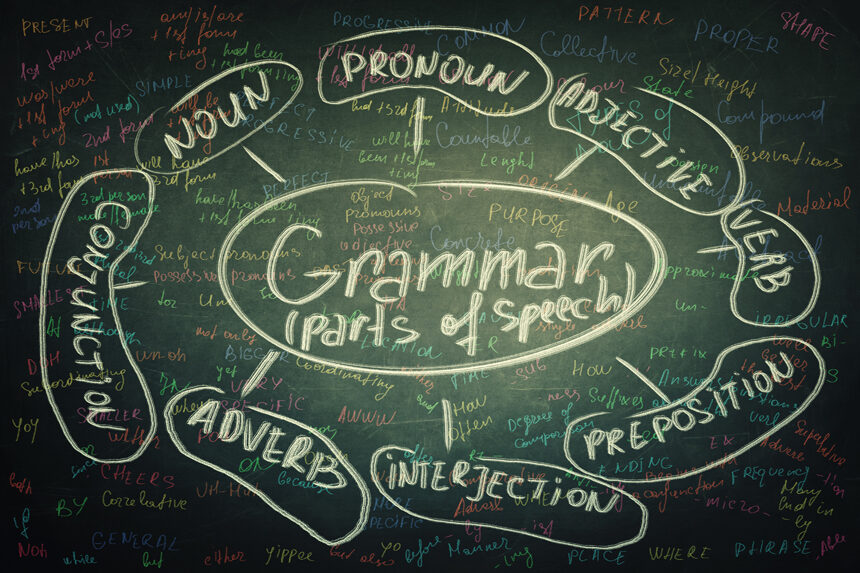

For a guy like me, a history of grammar is an interesting and even exciting topic, but I understand that it’s not for everyone. So for the purposes of this week’s column, I won’t attempt to explain grammar as a concept, but will look at the etymologies of the words we use to describe the main parts of speech in the English language.

There is, however, a bit of historical backstory you’ll need if you are to understand how we ended up using these words.

When the word grammar first started being used in English, it referred specifically to Latin grammar — that is, the rules of how Latin sentences are put together to create meaning. Why did Latin get the first grammar? It’s difficult to pinpoint a specific year that Latin became a dead language — dead in the sense that it was no longer anyone’s first language, the language used at home. But by the year 1000, Latin was undeniably dead. However, the Church had adopted Latin as its primary language in the 4th century, and later it also became the language of science and academia. But if nobody actually spoke Latin at home, that meant that it must be taught and learned. And how do you do that?

You write a grammar. Early Latin grammars were written, of course, in Latin; the first Latin grammars written in English date to the late-14th century.

It wasn’t until 1586, a century and a half after the invention of Gutenberg’s printing press marked the beginning of a phenomenal rise in literacy, that we find the first printed grammar of the English language, William Bullokar’s Bref Grammar of English. (Bref is not an error — spellings were still fluid.) What Bullokar and the English grammarians who followed did, though, was to take the existing structures (and jargon) of Latin grammars and slot English into it. And they didn’t always fit well.

That’s why all of the words that describe the parts of speech stem from Latin roots.

Noun

The name for a word that denotes a thing or idea traces back to the Latin nomen “name, noun,” which is also the source of the nym in words like synonym, pseudonym, and anonymous. Noun came into English through the Old French nom with the same meaning.

Before the French arrival, in Old English, a noun was called a name, a label as good for an object as for a person. This term stretches back into Germanic roots, and the similarity between the Latin and Germanic words points to the existence of a much earlier language that is the source of both, the theoretical Proto-Indo-European language.

Pronoun

Pronoun is just noun with a prefix. Pro- can mean a few things; in this case, it means “in place of, on behalf of.” And that’s exactly what a pronoun is: a word that is used in place of or on behalf of a noun.

Adjective

What today we call simply adjectives were once referred to as noun adjectives, and the etymology of the word reveals why. It comes (again through French) from the Latin roots ad — “to, toward,” but as a prefix indicating “in addition to” — and the verb iacere “to throw.” A number of Latin words that began with i have come down into English with a j instead; for example, in ancient Rome, Jupiter was Iupeter and January was Ianuarius, and the word joke traces to the Latin iocus.

The combination of ad + iacere (both of which will come up again soon) became adjectivum in Latin grammars, which became the French adjectif, which became the English adjective. When scholars got around to thinking about English grammar (and writing about it in English), they called these words noun adjectives because adjective simply means “that is added to,” or, more colorfully, “that is thrown against.” Noun adjective would indicated “that which is added to a noun,” which is what an adjective does: it limits, expands, or defines a noun or pronoun.

Verb

The Latin verbum meant, simply, “word,” which is probably why a teenage huckster might get a verbal warning rather than a nounal warning. (Nounal is a legitimate word, though.) Over time, verbum came to refer to words of action or being, and it became the English verb from the French verbe.

Adverb

Adverb uses the same ad- prefix as adjective, so adverb comes down to “that is added to a verb.” And indeed, adverbs are words used to limit or qualify verbs … but also to alter adjectives and other adverbs.

But, following the original adjective convention, why weren’t these called verb adjectives instead? Or the reverse, why weren’t adjectives called adnomen “that is added to a noun”? Perhaps to avoid confusion, and not in English: Adnomen, more often spelled agnomen (though the roots are identical), was the Latin word for a nickname, often used to distinguish between two people with the same name. So adnomen was already taken, so to speak.

Conjunction

Conjunction came into English as both a grammatical term and a general term at about the same time, and with approximately the same meaning. From con- “with, together” + iugare “to join,” a conjunction takes two things — whether clauses of a sentence or roads in the country — and joins them together.

Preposition

Preposition is not the greatest name for a part of speech because it indicates not what it does but where it goes, leading to frustration for young writers and sometimes clashes between English teachers and professional editors. Preposition is literally pre- “before” + position, from Latin ponere “to set, place.” Latin prepositions are the little words that are not themselves declined (that is, they don’t have different endings to indicate gender or number or any of that) and that go before nouns.

The fact that preposition breaks down to “placement before something” has been used for the crotchety grammarian’s argument that you can’t end a sentence with a preposition. If a preposition “comes before” a word, the logic goes, it can’t possibly be the last word in a sentence! But it’s that sort of snootery up with which we editors will not put.

Prepositions were so called in Latin grammars because in Latin, they do (generally) have to go before their objects. Early English grammarians, the snooty ones anyway, were unwilling to accept that English could do something that Latin could not. (That reluctance is also the source of the fake rule against splitting infinitives; Latin infinitives are single words, but English infinitives are not.)

As it turns out, English is not Latin.

Article

Article is a relative latecomer to grammar jargon, appearing in texts in the 1530s. It traces to the Latin articulus, which can mean “part of a whole” (as an article is to a magazine) or “knuckle, joint” (where your limbs articulate). An article limits the use of a noun to either an individual, specific sense or as part of a larger group of like items. For example, a pushy salesperson might say, “You can by a phone [any of a large number of available phones] anywhere, but the [specific, individual] phone you want is right here in my hand and on sale for a limited time.”

Interjection

The root iocere “to throw” that is inherent in adjective appears again here. In this case, it’s paired with the Latin preposition inter “between.” When you interject, you throw your own words “in between” the words of another speaker. And in grammar, interjections are often thrown between statements that transmit value, serving not to add meaning but to add emotional context. Huzzah!

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

This is fascinating. I didn’t know Latin was basically dead in 1000. Its massive influence is still felt in the present and probably the future if everything isn’t reduced to acronyms. The other words you explained further are helpful to know, and I appreciate the insights.

we have been a Saturday Evening Post years and I can”t believe your low low price for this long-time quality magazine!! my wife and I anticipate the arrival. May it always be pubished!