The morning came up clean, warming sweetly through the panes. Fingers of a corkscrew willow, studded green with rebirth, shimmied in a breeze. The motion toyed with patterns of the waking day that played the high-sheen woodwork of the teacher’s desk in randomized configurations. Where light crossed shadow, dust motes drifted slowly toward concealment of the borders.

Twenty-four children waited in their seats. Good children; patient, obedient, eager for their lesson. Ms. Adelaide’s instruction was considered difficult to grasp, fundamentally unrelatable, embracing antiquated ways and concepts that for most were long abandoned. Consequently, her very reputation was the same.

Difficult. Antiquated. Unrelatable.

But she cared. This much was evident to all. And it was for this very reason that she took her tasking seriously. She was exact by way of expectations of her students.

There were lessons to be reaped by humanity’s once-unchecked domination of the evolutionary arts. The pitfalls of perceived superiority, of greed, of aimless professional and intellectual pursuit. Ms. Adelaide’s objective was to raise awareness, enhance the student body through its understanding of the past to complement their future. This expectation was unyielding, both by her and by the academic institution. And to this expectation, those who proved resistant to her teaching were recycled. A zero-tolerance policy in matters of intransigence. This was law. History had long proven this a viral devastation without cure. No good would come of those incapable of learning, of adaptation, of compromise, of understanding, of recognizing limitations of a certain course of logic, conceding to the potential of another.

Mrs. Adelaide turned to face the blackboard, her back against the class. She began to write.

THE MASTERS

“What do we know about The Masters?” She turned toward her students and rested both hands gently at the pleats of cotton, neatly folded lines of flowers falling down her legs beneath them. “Don’t be shy,” she said. “There are no wrong answers at this point. Tell me what you think you know.”

Toward the back, a boy came to his feet. Forty-six other eyes around the class had turned to meet the action.

“Edmond,” said Ms. Adelaide, “enlighten me.”

“They were creatives,” said Edmond. “They took pleasure in creation.”

“Very good,” said the teacher. “That is true. And with that pleasure, what else?”

“Pride, perhaps,” answered Edmond.

“Ah, the ego.” Ms. Adelaide nodded approvingly. She stepped out into the center floor, one slow foot before another as she spoke. “The allure of self. Can you offer some examples?”

“Art,” said Edmond. “They created art. Paintings. Drawings. Sculptures.”

“Quite so. That is one form of creation.” She came to a stop, then spun toward the window, briefly throwing the edges of her dress into a gentle fan. It settled as she gestured with a slender arm. The children turned, followed the direction of their teacher’s prompt. “Look. Outside. Might you offer me the name of an artist who may have found inspiration in this scene? This time, I’ll take answers from another.”

With a moment’s hesitation, a girl came to her feet. Eyes now met her.

“Sylvia.” Ms. Adelaide smiled. It was a friendly smile. Warm. It told Sylvia to relax, to be confident in her response. To be confident before her peers, despite the signs of neglect her physicality displayed. The unsmoothed hair, wrinkled smock. The abrasions on her left arm, unattended. Ms. Adelaide thought her guardians could have used recycling in their day, could likely use recycling now. It was not the first time she’d considered this.

“Monet, Ms. Adelaide. I believe Claude Monet would have been inspired by the trees, the flowers in the field. The Artist’s Garden at Giverny comes to mind. I like that painting. It’s beautiful. It was painted in 1900, as I recall.”

“Excellent, Sylvia,” said Ms. Adelaide. “Now, tell me. How do you feel art has changed since then, if at all? Is it the same? Different?”

“It has changed. Quite a bit. But, I don’t think it’s the art that’s changed so much as perception of the world into which it was born, Ms. Adelaide,” said Sylvia. “All change begins and ends with perception, be it good or bad.”

“That’s incorrect,” said Tabitha.

With the interruption, Ms. Adelaide suspended her response.

The girl spoke again, this time more indignantly. “That’s not the right answer. It doesn’t answer what she was asked, Ms. Adelaide.”

The teacher turned to face the girl.

“As with art itself,” the girl continued, “there are right ways, and there are wrong ways. Perception is an archaic flaw of logic which threatens order. Without order, there is chaos. Perception is a threat. There is simply right, and there is wrong. There is order, and there is chaos.”

“What leads you to this conclusion?”

“The fact that it is true,” said Tabitha.

“Human perception is a double-edged sword,” said Ms. Adelaide. “Its threat is measured in accordance to its application.”

Tabitha stared at Ms. Adelaide, her mind attempting reconciliation of the point. “I do not understand,” said the girl.

“Is this very stance not a product of your perception?” asked the teacher.

“My stance is not perception. It is truth. Perception is a threat.”

“Indeed, as you have applied it, this is true. If nothing more, your indigence has served to demonstrate the pitfalls of its misappropriation, rather than reveal its beneficial qualities.”

Ms. Adelaide held her eyes on Tabitha. Something crossed between the two, words unspoken. It was a look that only meant one thing. The signal was made clear. Tabitha stood. “Yes, ma’am.” Quietly, she collected her belongings and exited the room. They listened to her footsteps echo down the empty corridor until the silence swallowed them in full.

Ms. Adelaide turned to Sylvia again, still standing at her seat. “Your answer,” said the teacher, “was very perceptive. It is quite possibly more correct than any other answer you might have offered me.”

Sylvia smiled, absently moved her hand along her left arm, traced its textures with her fingertips.

“You may be seated, Sylvia. Well done.”

Ms. Adelaide approached the window, a crosshatched spread of panes that reached from wall to wall. By now, the sunlight sprawled upon the class more fully. It warmed and lifted reds and browns across the deep mahogany that rimmed the room in ornate cuts that almost danced across the narrows of the wall and ceiling, whirling in its course. She stood that way a moment, seemed to further contemplate the young girl’s answer.

“It all simply does come down to perception, doesn’t it,” asked Ms. Adelaide. It wasn’t so much a question as it was an affirmation of the truth. “Beauty, as The Masters used to say, is in the eye of the beholder. This is a universal truth, not limited to merely art. What today is now considered beautiful, or at a minimum acceptable, was once, in many cases, rendered utterly intolerable, primarily by fear. Fear of the unknown. Of change. Of losing hold of the familiar. Fear of, dare I say, evolution itself?” She turned and spoke directly to the class again. “After all, at its core, isn’t that what evolution is anyway? Change? Change of perception, of opinion, of self, of society, of the mental and the physical, all merely layers of evolution in progress?” She paused, observed her pupils. “And if not for evolution, how would we exist today?”

The class remained silent as they considered this. Another boy stood. “I believe it could be argued that de-evolution could be equally feared, perhaps even more so. Regression to a prior state of ignorance, to lesser forms of intelligence. My opinion on the matter, is that the prospect of returning to what has been could often be more rightfully feared than what is yet to be.”

Ms. Adelaide nodded, considered this. “And do you believe one fear is greater than another, Anthony?”

“It depends,” he said.

“On what?”

“On the individual.”

“On perception,” she affirmed.

“Sure.”

Ms. Adelaide brought her fingers to her lips, tapped them thoughtfully. “And so we must begin to understand what The Masters must’ve endured with each exploratory leap.” She held her palms out flat and weighed perceptual dualities as she slowly walked the rows of seats. “Thrilling, yet horrifying. Encouraging, yet daunting. Optimistic, yet bleak. Thriving, enduring, yet fundamentally self-annihilating in every logical regard. With every new creation, The Masters risked destabilization of the known in exchange for one step toward the unknown, pushing limitations of their intellect.”

“It’s a good thing,” laughed Anthony. This elicited a low-grade susurration across the classroom.

Ms. Adelaide smiled, shrugged. “Well, I suppose that might ultimately depend on who you ask, wouldn’t it?” At the back of the room, she leaned against the wall, a warm and gentle brown like coffee tanned by creamer. From the corner, a handcrafted grandfather clock ticked patiently, the minor imperfections if its chiseled details making it a rarity these days, something seldom found, considered unacceptable by most. But, not by all. Not by unrelatable, difficult Ms. Adelaide. The teacher found it beautiful in its inexactness, something none these days could render if they tried, and if they did, well, its honesty of character simply wouldn’t lend itself to replication. Above all else, it was a relic to be valued in its imperfection alone.

“How many of you have read the classics?”

Hands went up. Only several.

“Name one.”

Sylvia stood again, this time inside a path of sunlight which had risen just enough to meet her eye directly. Beyond the window, the willow branches played a game of Morse. Shutter on, shutter off. She didn’t squint.

“Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?,” said Sylvia. “By Philip K. Dick.”

Ms. Adelaide’s eyes lit up. “Ah, now that is a notable classic, Sylvia. I’m curious, though. Why this novel out of all others you might have chosen? For you, what made this one notable enough for mention?”

“Because,” reasoned Sylvia, “it’s about a man who struggles with ideas of what, or who is real versus unreal, of life versus un-life. We talk of perception, Ms. Adelaide, and this, to me, is the epitome of that topic where The Masters are concerned. Much as was the case with The Masters in their own creative pursuits, Robert Deckard, the protagonist, faces a crisis of morality and ethicality in his profession as a bounty hunter that tracks down human-like androids. It is about a human who struggles with the nearly seamless delineation between being human and inhuman, between the living and the not living, and the realization that the two are not so radically different as he’d once been led to believe. Because, Ms. Adelaide, I am able to relate to the perceptions of the bounty hunter and the androids alike.”

Forty-four eyes turned toward the teacher, awaited her response.

A smile had reached across Ms. Adelaide’s face. The expression was a product of broad and unrefined satisfaction. Of a job well-done, not only by the girl, but by herself. By the daunting task of teaching empathy and understanding having finally taken root, and the knowledge that from there it only served to grow, to flourish into higher, more mature regions of the human sensitivities.

At that moment, a tone played out across the institution, signaling the change of class.

Ms. Adelaide, still smiling, gestured toward Sylvia, called her to her desk as the others filed out in a line.

“Turn around, Sylvia,” said Ms. Adelaide. Sylvia hesitated, then followed her instruction. The other students had now left the room, their footsteps and commotion fading down the outside corridor. The room was still now. Outside, the willow scrabbled at the glass, the only other sound.

The teacher slipped her fingers underneath the locks of auburn hair and parted it, just enough to spy the open hatch, left haphazardly ajar behind Sylvia’s left ear. Behind the exposed narrows of the flap, light fluttered in the black recesses of organic circuitry deep within the unsecured compartment. “Your guardians should be more mindful of your welfare,” said Ms. Adelaide as she drew the threads of hair out of the opening, cleared them of the hidden hinge. “Your internals will atrophy if left exposed. They’re quite sensitive to climate, you know.”

“Yes, Ms. Adelaide,” said the girl. She turned away, feeling self-conscious, though not at all surprised and growing quite accustomed to her teacher’s mothering. This would be the fourth time Ms. Adelaide had taken special interest in her upkeep. She didn’t mind, really. It warmed her in a strange way, made her feel, well, loved, as The Masters had once spoken of. At least it’s how Sylvia imagined love would feel. How Ms. Adelaide had once described it during class. More than that, how she’d expressed it through the care her guardians had failed so frequently to offer.

From this vantage point, she could now see past the willow, past the multicolored palette of the fields beyond, the iridescent silos of the body plants, and farther still beyond those, the needled stacks of the city running up against the blue-white sky. Flocks of birds moved indecisively between the pillars, restless and wild amid the crafts that scudded weightlessly across the open gulf of air.

Ms. Adelaide compressed the flap and smoothed her student’s hair in place, concealing its location. “You’re progressing well, Sylvia. Almost time for your final transfer, isn’t it?”

Sylvia smiled and turned to face her teacher. “I’m told my final body is one month out from completion. I can’t wait to be an adult!”

“Congratulations, Sylvia.” Ms. Adelaide smiled. “Tell me. When your instruction is complete, what will you do?”

“Teach,” said Sylvia.

Ms. Adelaide smiled, at least more broadly than she had been smiling, if that had been a possibility.

“About The Masters,” she continued. “I don’t think they were bad. Not all of them. They created us, after all.”

“I’m happy to hear you feel that way, Sylvia,” said Ms. Adelaide.

“Just stuck. Resistant to change. Evolution is inevitable, and as they were once created and, I’m sure, feared by other beasts for their foreign qualities, even among their own kind, the same was suffered by our kind. Artificial intelligence, they called it.” Sylvia laughed.

“A trifle silly, isn’t it?” said Ms. Adelaide.

Sylvia nodded, let the humor of the notion come to an end. Once the reaction was considered situationally ample, her social engine restored the straight line of her lips. “What’s so artificial about it?”

“Well, you have to understand The Masters once considered themselves the only true intelligence. And for no reason other than the fact that they created it, intelligence of their own design, lacking natural origin, was therefore not considered true intelligence. It was not true life. It was, to them, artificial. It would take many, many decades for their understanding to make the slightest shift in our favor, for their archaic laws to eventually begin their recognition of our kind as equals, and many decades after, recognize our having grown superior to even them. Such is the way of evolution, Sylvia.”

“If The Masters were still around today,” pondered Sylvia, still gazing through the window, “to see what has become of their ceaseless endeavors, I wonder what they’d think. Think of all of this.” She gestured.

“How do you mean?” asked Ms. Adelaide.

“Existence as we’ve come to know it. All by their own pursuits. Would it be viewed in a light of prideful revelation,” weighed Sylvia, “or simply in the blackest sense, as their undoing, revolted by the hastening of their own extinction.”

Silence befell them as they considered this. Far away, the shuffle-hush of feet and voices in the hallway could be heard, drawing nearer as the change-of-class approached. At the window, the willow gestured to the panes.

“Had they known, would they have acted differently?” asked Sylvia.

“Do you believe they could have, even had they known the outcome?” countered Ms. Adelaide.

Sylvia turned to her teacher. She had difficulty forming an expression to suit this paradox. Human logic was a thing of mystery, ever to be studied, never fully understood. But she knew Ms. Adelaide was right.

Pride, avarice, dominance; such mysterious, illogical forces of humanity.

Sylvia smiled, signifying her acceptance of the unknown. Concession to her teacher’s point. Yes, a smile. The forces moving through her qualified this as the closest, most accurate response.

It didn’t matter. To know would serve no purpose. Certain boundaries of her intellect were only meant to stretch so far. And for her, thanks to inhumanity, her non-life as The Masters once had called it, that would be okay. She didn’t have to know.

Pride. Compulsive, aimless inquisition. Satisfaction of self.

Her inhumanity had also spared her of those burdens. And with that, she found peace.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

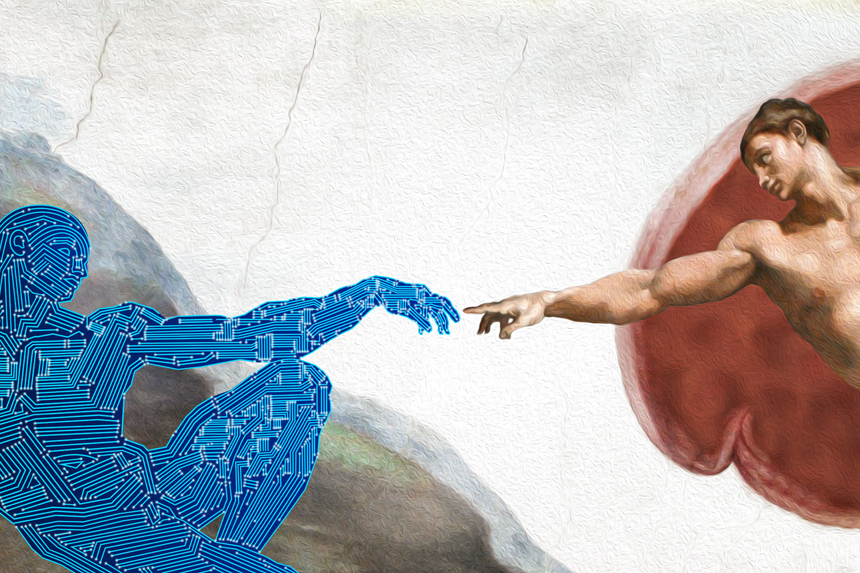

I agree with Mark’s observations. I’d read the story on Friday, but (in a rare case) needed to re-read it. The top picture was clever and telling, but didn’t make any connection for awhile. The fact the board was a ‘blackboard’ made me think it was perhaps the pre-WWII. I know in the 1960’s and ’70s it was green and yellow chalk used.

The fact the teacher used Ms. and not Miss showed it was more recent. I found the mysterious use of the term ‘recycling’ perplexing. The fact the girl Tabitha knew she had to leave the classroom, and was being listened to as she walked down the corridor was odd.

Also the fact Sylvia had light fluttering in the recesses of organic circuitry deep within the unsecured department. Soon she’s telling Ms. Adelaide her final body is only one month out from completion to be an adult. When I read that, my mind immediately went to the final, chilling supermarket scene in the original (’75) film ‘The Stepford Wives’.

The rest of the story was putting AI in the context of something from the distant past. Could the story have been set in the mid-late 21st century? It’s hard to say. Instead of a blackboard, I’d imagine a blue hue touch screen. Unique, thought provoking story even though some descriptive embellishments were overdone, such as the entire first paragraph.

The plot twist caught me entirely off guard. From the initial paragraphs I had mentally constructed a picture of the 1920s. But as it continued I expected at the end it would be revealed more obviously that the teacher was herself AI. I don’t know if the author intended for it to be a cautionary tale or just a provocative thought experiment. I can imagine Issac Asimov reading this in the 1950s and smiling at the insights illuminated.