Apollo 14 astronauts Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell were relaxed and eager to get to work as the Lunar Module Antares touched down in the hilly uplands of the Fra Mauro crater on February 5, 1971. Over the next two days, they would deploy the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), conduct lunar geology investigations, and gather 94 pounds of rocks and soil for study back on Earth. Their time exploring the moon’s surface would total a record 9 hours, 24 minutes.

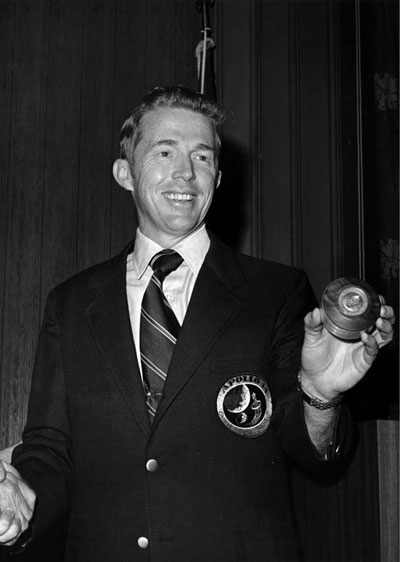

Orbiting miles above them, Command Module Pilot Stuart A. Roosa was deeply involved in his own work, which included photographing potential landing sites for future Apollo missions. Among them was the Descartes area, the planned landing site for Apollo 16.

Accompanying Roosa were an estimated 500 tiny tree seeds stored in a special container packed within his Personal Preference Kit, a small valise containing his personal effects. The seeds stayed in Roosa’s possession until splashdown on February 9, 1971.

Hundreds of trees were germinated from the seeds Roosa brought back with him. Popularly known as Moon Trees, their amazing story had pretty much faded into history until Artemis 1, NASA’s first flight test of the Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft in November-December 2022. In honor of Apollo 14, 2,000 tree seeds were carried aboard the Orion as it traveled beyond the moon and back, providing the potential for a new generation of Moon Trees more than 50 years after the first.

Roosa’s involvement in the tree seed project sprang from his long association with the USDA Forest Service. He had joined the agency at 17, eager for adventure as well as a paycheck, and first worked in Idaho on a project to control blister rust disease in white pine trees. “He was also part of a wildland firefighting crew and met a lot of smoke jumpers, which are firefighters who parachute into remote areas,” reports Heidi McAllister, assistant director of conservation education with the Forest Service. “He became a smoke jumper and made several jumps into fire zones in Oregon and California during the 1953 fire season.”

Soon after, Roosa joined the U.S. Air Force Cadet Program and eventually became a fighter test pilot. In 1966, NASA selected him for its astronaut program. When it was announced that Roosa would pilot the command module for Apollo 14, he was approached by Forest Service Chief Edward Cliff to take a selection of tree seeds with him to the moon. Roosa was happy to oblige.

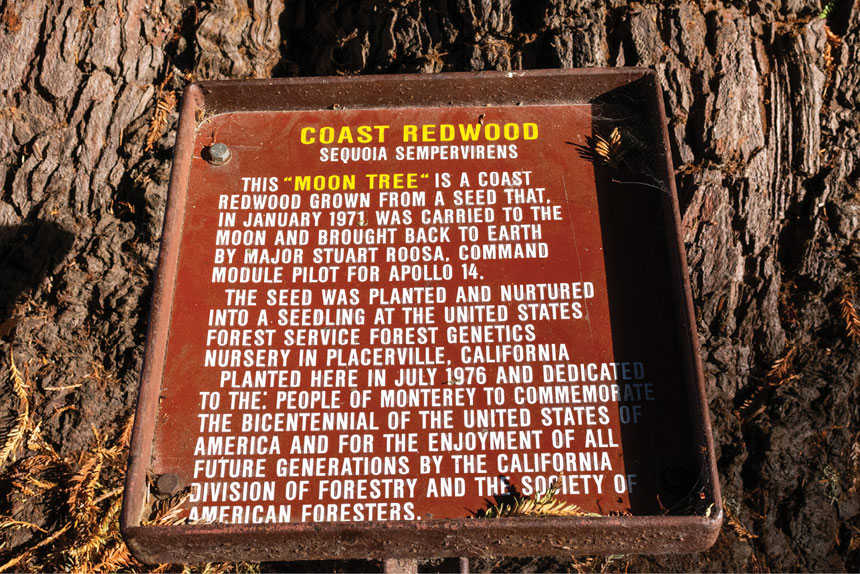

Five species of tree seeds traveled aboard the Apollo 14: loblolly pine, sycamore, sweetgum, redwood, and Douglas fir. The seeds were sealed in small plastic bags and stored in a metal container that could fit comfortably in the palm of your hand. A selection of control seeds remained on Earth for comparison.

“It wasn’t a formal NASA experiment,” observes John Uri, manager of the Johnson Space Center History Office in Houston, Texas. “The Forest Service thought, hey, why don’t we see what happens if we fly a bunch of seeds into space, because that hadn’t been done before. What would be the impact if they went through the Van Allen belts and were exposed to radiation and so forth. Though it was a pretty short flight, just nine days, they wanted to see what would happen.”

The space-faring seeds survived the journey but barely survived the mandated decontamination process upon their return. When placed inside a vacuum chamber, the sealed packets burst open, casting seeds everywhere. “It was feared that the seeds would be inviable,” says McAllister. “They were collected and sorted, and almost all germinated without a problem.”

NASA germinated some of the seeds in Houston, but they did not survive long because the facilities were inadequate. A year later, space-flown sycamore, loblolly pine, and sweetgum seeds were sent to what is now the Forest Service Southern Research Station in Gulfport, Mississippi, and redwood and Douglas fir seeds went to the Forest Service Pacific Southwest Research Station in Placerville, California. These efforts were extremely successful, producing around 450 healthy seedlings, McAllister reports.

Moon Trees were huge news in the mid-1970s, and everyone wanted one. It was NASA’s responsibility to distribute the trees, and scores of seedlings were donated to schools, universities, parks, and government offices nationwide, many in celebration of America’s bicentennial in 1976. A loblolly pine was planted at the White House, and trees were planted in Brazil and Switzerland and presented to the Emperor of Japan, notes the official NASA history of the Moon Trees. Seedlings were also planted in Washington Square in Philadelphia; at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania; in the International Forest of Friendship in Atchison, Kansas; at Arlington National Cemetery; and at various universities and NASA centers.

In a telegram to U.S. Bicentennial Moon Tree planting ceremonies, President Gerald Ford said, “This tree which was carried by Astronauts Stuart Roosa, Alan Shepard, and Edgar Mitchell on their mission to the Moon, is a living symbol of our spectacular human and scientific achievements. It is a fitting tribute to our national space program which has brought out the best of American patriotism, dedication, and determination to succeed.”

Uri was living in Philadelphia when the first Moon Tree was planted in Washington Square Park in 1975. “I later walked by that tree many times and had no clue until a friend pointed it out to me,” he says. “Unfortunately, the original tree died a number of years ago, so they planted a second one, which also died a few years later. The last time I visited, a stick was all that was left of it.”

Over the years, many dead Moon Trees were replaced with second-generation trees grown from seeds from the originals. In 2019, a garden of 12 second-generation Moon Trees was planted at the Kennedy Space Center after the original tree was destroyed by Hurricane Irma in 2017. Uri’s Houston office at the Johnson Space Center also overlooks a second-generation Moon Tree, and Uri enjoys telling new employees about its history. “It’s not publicized at all. It’s one of those forgotten pieces of Apollo history,” Uri says. “I love telling stories about it because it gives the Apollo program a much more human feel.”

After the initial interest died down, the world essentially forgot about the Moon Trees. In 1996, Joan Goble, a third-grade teacher in Cannelton, Indiana, reached out to NASA requesting information about a Moon Tree that was planted in 1976 at Camp Henry F. Koch, a Girl Scout camp. Dave Williams, now the acting head of the NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive, fielded Goble’s inquiry, and was able to find bits and pieces about the Moon Tree project through the NASA History Office.

“I thought, wow, this is such a neat story, and I didn’t want to let it go,” Williams says. “I wrote a page for the NASA website, a barebones history of the Moon Trees.” He also asked anyone who knew the location of a Moon Tree to write to him, and included his email address. “Sure enough,” he says, “I started getting emails, including from people at the Forest Service who had worked on the Apollo 14 project.”

Fascinated by the long-forgotten experiment, Williams made it his mission to find and catalogue as many Moon Trees as he could. He has located around 120 Moon Trees to date, of which approximately three dozen have died. The search is difficult because many Moon Trees have no signage indicating what they are. Several Moon Trees have been identified through archived newspaper articles from the Apollo 14 era. (Williams’s Moon Tree catalogue is available at https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/lunar/moon_tree.html.)

Stuart Roosa’s daughter, Rosemary, who was seven years old when Apollo 14 launched, is also working to spread the word about the Moon Trees through the Moon Tree Foundation, which distributes second-generation Moon Trees to schools and other organizations. It was the Moon Tree Foundation that donated the 12 trees to the Kennedy Space Center in 2019, as well as the tree John Uri can see from his office at the Johnson Space Center.

“Our motto is ‘Planting the Seeds of Inspiration,’ and our mission is to inspire, unite, and conserve,” Rosemary Roosa says. “I tell people, just as the world was united when Neil Armstrong stepped foot on the moon, these trees have a uniting essence as well. It’s really inspirational. During a recent Moon Tree planting in Flagstaff, Arizona, a boy told his teacher he was inspired to become an astronaut.”

A new generation of Moon Trees will sprout from the seeds that traveled aboard Artemis 1, which launched November 16, 2022, and spent 25 days in space. Giant sequoia seeds replaced redwood seeds because the redwoods have a limited natural range, notes a NASA report on the Artemis mission. The seedlings should be ready for planting in mid-to-late 2024, the exact timing depending on the species and location.

“Moon Trees provide communities with a real connection to the Apollo program and the moon,” observes Williams. “I see this as community involvement in a much larger international endeavor, meaning the space program itself. You can touch a Moon Tree and know that the seed that made the tree went around the moon. I think that’s so cool.”

If you know of a Moon Tree in your community, Dave Williams would like to hear from you. Send him your findings at [email protected].

Don Vaughan is a freelance writer based in Raleigh, North Carolina. His work has appeared in Writer’s Digest, MAD Magazine, Scout Life, VFW Magazine, and elsewhere. He has also written or contributed to more than 30 books and is the founder of Triangle Association of Freelancers.

This article is featured in the July/August 2023 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I’m old enough to remember Apollo 14 live, it was magical to come home from school to see a programme called “Live from the Moon”.

Here in London UK, in Streatham, there are a row of trees all commemorating my favourite astronauts. I saw them from a London bus and it seemed the plaques with the names are now too high to see easily from the ground . They have been there a while and the local council Lambeth don’t seem to have a record of why they are there.

If they aren’t “Moon trees” which now I’d so like them to be them they are still a mystery to the locals they only appear in a couple of Web posts.. …. To be honest I know little of how long it takes a sapling to grow so high but 40 years seems reasonable to me!

Its a real shame that in Canada we N E V E R heard of astronaut Stuart Roosa.

This is new to six of us who have read this article.

Sad.

We are grateful to read all about him.

There are probably a couple of others we have N E V E R heard of either.

Armstrong, Aldrin and others get the “front page” when mentioning anything to do with the “moon shots”.

Sad that others like Roosa are in the dark corner of history without a light shining on them.

Thank you for telling us about this otherwise unknown, but, clever, brilliant man.