Like many gardeners, I’ve been dismayed now and then by late frosts, damaging storms, and other unwelcome weather events. The thought of tweaking the climate a bit to help my garden is a tempting dream. But the violent storms that swept the country throughout the spring, coupled with this summer’s record-breaking heat and New England’s catastrophic floods, are stark reminders no one can control Mother Nature. She plays rough sometimes, but you have to admit she’s generous as well, giving us handy items like oxygen and fresh water (her sunsets aren’t too shabby, either).

Even though she’s incomparably stronger than we are, Mother Nature is happy to bless our gardens with bigger harvests and longer “personal growing seasons” if we view her as an ally, not an adversary. There are ways to coax more bounty from our gardens while still keeping them in top shape.

Obviously, there’s no one date for gardeners to plant peas or pull carrots. It depends where you live. A lifelong northerner, I recall helping a farmer load seed potatoes from an insulated bunker, in February at about -40 degrees, into a semi-truck headed south. It was hard for me to picture that in Florida, fields were plowed and folks were planting potatoes. Our crop calendars didn’t match – it was like comparing icicles to oranges.

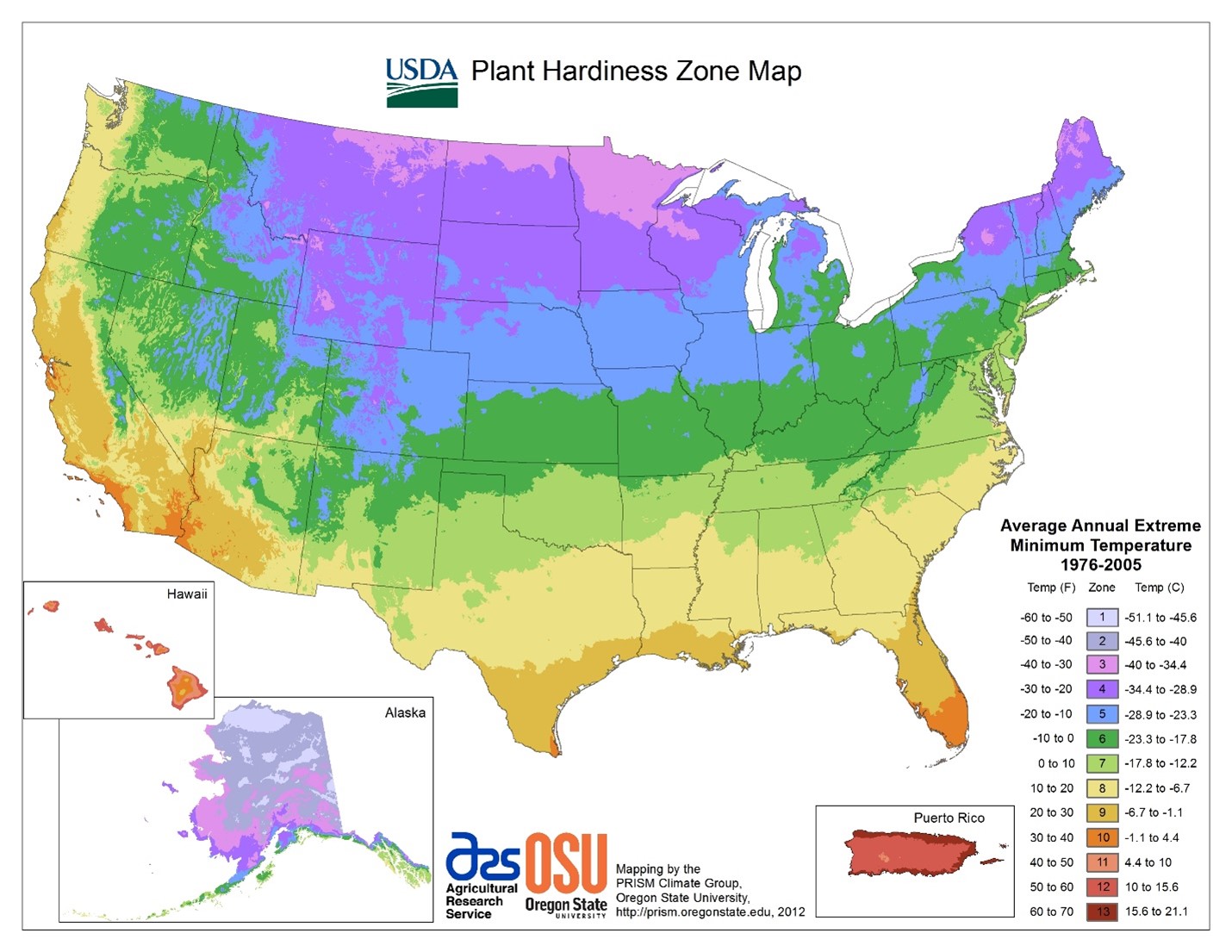

To untangle such issues, the U.S. Department of Agriculture created the first Plant Hardiness Zone map in 1927. Zones range from 1 (northern Alaska, where I assume iceberg lettuce is grown) to 13 (Florida Keys, where it’s too hot to be a farmer anyway). Each zone is divided into “a” and “b.” Regions with similar temperatures (within 5 degrees) get a unique stylish color, so you can quickly find your zone. It’s a tremendous tool. Seed packets show planting dates by zone, and tags on fruit trees list suitable zones (note: on occasion, mistakes happen and non-hardy plants show up in stores – read the tags carefully).

In 2012, I got a hardiness upgrade: my land, which had been in Zone 3b for 50 years, was promoted to Zone 4a. I was so proud, until I learned every zone moved north to reflect real-life conditions.

Most of the U.S. lies between Zone 3 and Zone 10; that is, outside the districts of ice and fire. This means nearly every American can have a productive and enjoyable garden. Gardeners at high latitudes and elevations – anyplace winter is spelled “cold and snow” – face the challenge of planting crops after danger of frost has passed, while getting them to mature before autumn’s first freeze. Plenty of gardeners at mid-latitudes wish they could have fresh veggies later in the year, as well.

Here’s how you can extend the growing season, both early and late: Each layer of covering over a crop advances the conditions underneath by a full Hardiness Zone. One example of such a covering is an unheated greenhouse, for which few people have the space or funds.

Instead, you can take your garden someplace milder for a pittance without leaving home. Floating row covers, as they are known, are generally made of spun polyester, which is very inexpensive. Open-weave cotton is available too, but costs more. Though gossamer-light, these fabrics are surprisingly durable and will last for years if one is careful. They’re often used to cover plants at night if frost is expected.

To get the “tropical effect” described above, it’s essential to allow an air gap between the plants and the row cover.. This can be achieved with heavy (9 to 10 gauge) wire pressed into the ground and bent in a hoop over the crop at intervals along the row to create a mini-tunnel. Wire is easily gathered and stored for reuse.

Some gardeners use PVC conduit for a slightly taller tunnel, either for larger crops or as a second layer. With two tunnels, a gardener living in Zone 5, where the average minimum temperature is -10 to -20 Fahrenheit, can effectively put their plants into Zone 7 where the coldest night only dips down to between 0 and +10.

The purpose of row covers goes beyond protecting plants from freeze injury – it also pushes the dates of last spring frost and first autumn frost away. Under a single row cover, it will be from 4 to 10 degrees warmer than outside. A freeze-sensitive crop like basil could conceivably be fine after a night where it dropped to 28, or even 22 degrees. And you could be harvesting freeze-tolerant veggies such as chard, cold-hardy lettuces, endives, radishes, beets, and carrots well into early winter.

A second row cover will double this effect. Furthermore, crops that include spinach, winter mesclun mix, cilantro, kale and arugula can overwinter if you plant them in autumn in a low tunnel or under other season extenders like cold frames. This way you’ll have fresh greens before anyone else is thinking about the garden.

One of the best resources to help you garden is our nationwide Extension Service. There is an office in most counties in all 50 states. Find the one closest to you here.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

I only have a small garden but love your column! Keep up the good work!