Perhaps one of America’s most prolific female architects, Julia Morgan was a trailblazing figure for the modern feminist movement. While much of her work has been forgotten to history since her death in 1957, she was a pioneer of her field, designing more than 700 buildings throughout her 46-year career that have come to define California’s built environment.

Born in 1872 to Charles Bill Morgan and Eliza Woodland Parmelee, Morgan’s education was funded in large part by the Parmelee family fortune. In fact, both Julia and her younger sister, Emma, attended the University of California at Berkeley to pursue career paths not often encouraged for women at the time. While Emma went on to graduate from law school in San Francisco, Julia enrolled in the civil engineering program and became one of the first female students to graduate from the school.

After her graduation, Morgan began studying and working under Bernard Maybeck as a draftsperson. Maybeck was a well-known architect of his time, responsible for the design of the Berkeley First Church of Christ, Scientist, a building that came to define the Bay Area style of architecture through its use of natural, local materials.

A graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris himself, Maybeck encouraged his student to attend the school that was widely regarded as the preeminent architecture school in the world. Gaining admission to the acclaimed school proved difficult for Morgan, however, as she reportedly failed the entrance exams three times; according to historian Karen McNeill, “at least once for legitimate errors and once … because she was a woman.”

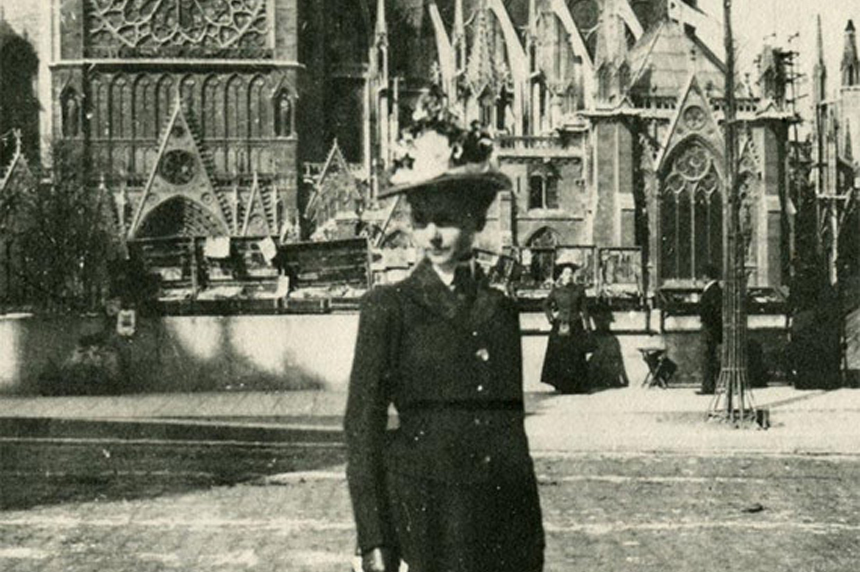

Yet Morgan soon became the first woman enrolled in the prestigious architectural program and, under the study of Parisian architect François-Benjamin Chaussemiche, the first woman graduate. While studying at the École, Morgan even won several prominent awards, receiving 3 medals and 26 mentions, including the second-place medal for the renowned Godeboeuf Competition.

Morgan stayed in Paris from 1896 to 1902, witnessing the rapid change in art and architecture that accompanied the turn of the century. While in Europe, Morgan became inspired by the architecture, quickly developing a style that complemented her Beaux-Arts training.

Upon returning to California in 1902, Morgan began working with the Berkeley campus architect John Galen Howard before becoming the first licensed female architect of California and opening her own practice in 1904.

Among her first projects was a bell tower on the campus of Mills College in Oakland, which she named El Campanil. According to McNeill, the mission-style design of the tower stood as a beacon of change, differentiating the institution from eastern architectural standards and signaling its status as a leading women’s college.

Perhaps most significant, however, was El Campanil’s survival of the 1906 Great San Francisco Earthquake, cementing Morgan’s status as one of California’s preeminent architects. Following the earthquake’s vast destruction of over 80 percent of the city, Morgan was commissioned for several projects, including the rebuilding of the luxurious Fairmont Hotel.

The success of the Fairmont Hotel went on to fuel much of Morgan’s professional success. Following the hotel’s re-opening, Morgan received a wide range of commissions, including churches, libraries, commercial buildings, and residential clubs, alongside hundreds of residences in Berkeley and Oakland Hills.

Morgan’s style varied widely throughout these projects, from Venetian Gothic and Tudor to Mission Revival and Neoclassical. According to Lynn Forney McMurray, the daughter of Morgan’s secretary Lillian Forney, “she could do any style” but her houses were always “built from the inside out; she thought about how the people were to live.”

Morgan’s career benefited greatly from the growing feminist movement. According to Morgan’s biographer, Sara Boutelle, “the networks that women had developed while campaigning for … women’s suffrage had made them aware of, and eager to hire, other women with diverse skills.” In fact, many of Morgan’s first commissions came from connections she had made through her college sorority, Kappa Alpha Theta.

Perhaps the most significant professional relationship Morgan would form, however, was with philanthropist and feminist advocate Phoebe Appleton Hearst. The two women first met in Paris during Morgan’s education at the École des Beaux-Arts, and upon her return to California, the young architect was hired to remodel the widow’s estate in Pleasanton, which she called Hacienda del Pozo de Verona (Estate of the Well of Verona).

Throughout Morgan’s career, Hearst continued to advocate for her work, persuading the National Board of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) to hire her to design their first conference center in Pacific Grove, California. Morgan spent the next 15 years designing and building Asilomar, or “refuge by the sea,” which came to be one of her most defining works. Throughout the construction, Morgan was careful to maintain the building’s California roots, featuring exposed wood trusses, redwood walls, and stone fireplaces. Morgan went on to have a long professional relationship with the YWCA, designing at least 30 buildings in 17 different locations across California, Hawaii, Washington, and Utah.

Phoebe Hearst also likely introduced Morgan to her most significant client: Phoebe’s son, William Randolph Hearst. Morgan’s first commission for the newspaper magnate was the Hearst Examiner Building — in a Spanish Mission Revival style — in Los Angeles.

Upon his mother’s death in 1919, William Randolph Hearst inherited the full Hearst estate and hired Morgan to build a residence at his ranch in San Simeon. He initially commissioned Morgan to build a modest bungalow, yet his vision quickly evolved into a full-fledged castle which he named La Cuesta Encantada, or “The Enchanted Hill,” complete with fragments of Spanish and Italian buildings Hearst purchased and shipped to California.

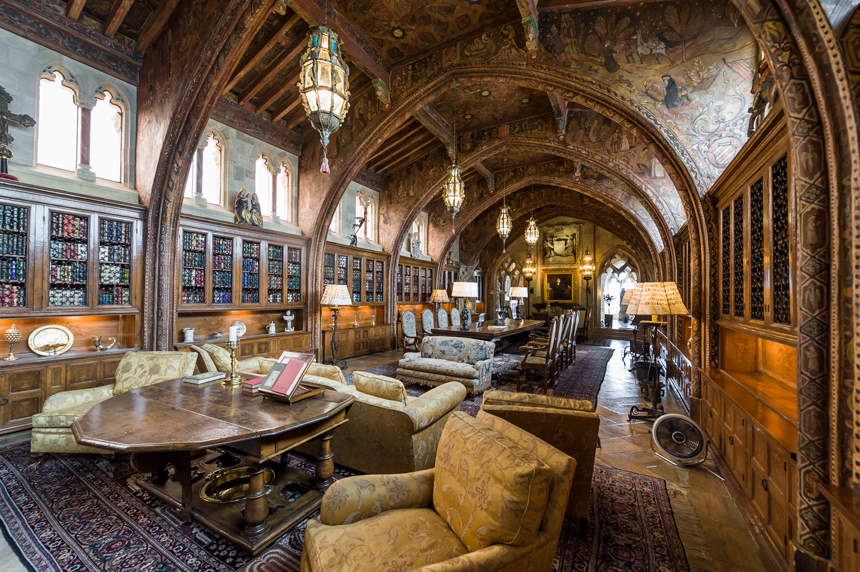

The project that became Hearst Castle would occupy Morgan for more than 20 years, evolving into a series of luxurious buildings across 127 acres with Hearst Castle at its center. As the main residence, the structure covers 68,500 square feet and contains 115 rooms, including 38 bedrooms, more than 40 bathrooms, a home theater, and a beauty salon.

Well-known for his capricious and often compulsive behavior, Hearst’s vision for his estate was constantly evolving. On more than one occasion, Hearst would request last-minute changes; he even chose to enlarge the Neptune Pool twice after its initial construction.

In keeping with Morgan’s focus on the lived experiences of her buildings’ inhabitants, the interior of Hearst Castle is surprisingly intimate; there is no grand staircase or imposing foyer, but instead a tiled entry that leads to a more contained living space.

Another of Morgan’s specialties was designing pools, of which there are two within the walls of Hearst Castle. While the Neptune Pool is an elaborate construction almost 104 feet long and 95 feet wide and holding 345,000 gallons of water, complete with an oil-burning heating system and Vermont marble, the Roman pool is smaller yet perhaps even more ornate, decorated with mosaic tiles from floor to ceiling and enclosed within marble walls.

The project at Hearst Castle occupied a majority of Morgan’s later years. In fact, Morgan found herself unable to complete it, in large part because of what she called Hearst’s “severe case of changeableness of mind.”

Upon her death in 1957, little was known about the accomplished architect. Morgan’s contributions were not widely recognized until the publication of Julia Morgan, Architect by Sara Boutelle in 1988, ushering the architect and her many accomplishments back into the public eye.

Since her death, Morgan has received several posthumous awards and recognitions for her work. In 1982, a Mediterranean Revival residence that the architect built for Charles Goethe of Sacramento was added to the National Register of Historic Places, and the building was later renamed the Julia Morgan House.

In 2008, Morgan was posthumously inducted into the California Hall of Fame, and she was the first female recipient of the American Institute of Architects Gold Medal, in 2014.

Julia Morgan’s steadfast dedication to her work is present throughout her career. Not only did she shape the architecture and built environment of modern-day California, but she led the way for women looking to secure their independence in a male-dominated world.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

She was an architect, but was she also an interior designer? Apparently, she was. Great, illuminating article.

An amazing article about an amazing woman. Thoroughly enjoyed reading this piece.

Jennie, I’ve got to hand it to you. You’ve outdone yourself with this feature on Julia Morgan whom I find spellbinding. She has to be one of the most gifted architects of all time. I love Diana and Nola’s comments here on the pools. If I didn’t know better, I’d swear the indoor Roman pool was or could have been a Styx album cover at one time or another. A mirage for both you and us, how can it be real? But it is, because of her otherworldly talent and wonderful taste!

I’d like to see a swimming pool in Greece that even comes close to the Neptune pool. Very impressed how she combined the elaborate, ornate and grandiose with the livable and practical. Ergonomics if you will. Interesting how this word dates back to 1857, a full 100 years before she left us.

The Asilomar conference center is such a sight to behold, as is the Spanish style Examiner building. Julia Morgan is absolutely is the female equivalent to Frank Lloyd Wright. I’m glad she’s finally gotten much overdue recognition and credit in the past 35 years. She’s the Miss America of California architecture, and by extension the entire United States. Her visionary work must never be forgotten, and we’re VERY fortunate for her contributions to this state culturally and historically.

When a resident of Calif. I visited San Simeon more than once. As a swim teacher it was all I could do to refrain from “accidentally” falling into either of the pool, both pure luxury & beauty.

The pools are just awesome . Too pretty to swim in