The cotton was high that summer, the year I turned twelve. The air hung hot and thick around us as we chopped and hoed our way up and down the endless field rows. From time to time, if we were lucky, a breeze might begin to stir and give us occasion to pause a minute, prop on our hoe handles, and survey our work.

Under the shade tree at lunchtime, we were too starved and thirsty to do much talkin’, but, if we did get started, there was only one topic of conversation that summer, “the books.”

You see, Miss Ester Cochran, an elderly lady of distinguished lineage in our county, had passed away. She had spent the last few years of her life in England with a wealthy cousin of hers. On occasion, Miss Ester would send a letter to our pastor updating him on her health problems and telling about her latest European travels. Preacher Hicks always obliged Miss Ester and faithfully read her letters to the congregation when we gathered together. After all, her family had donated the land the church house was on, and the Cochrans did have the tallest markers in the churchyard cemetery, so we felt it was our duty to stay abreast of Miss Ester’s doings. Everyone knew she was the last of the Cochran clan, at least in our neck of the woods, and, when she was gone, well, the local hierarchy would never be the same.

Then one day it happened. Preacher Hicks got word from England that the angels had come callin’ for Miss Ester. We were told that her final restin’ place would be in a little village cemetery in the English countryside, though arrangements had been made through the bank at Charleston to erect a memorial marker for Miss Ester in our churchyard right alongside the rest of the Cochran markers.

The other bit of information Preacher Hicks passed along concerned “the books.” Apparently, the English cousin had told our pastor that one of Miss Ester’s last wishes was that her beloved books be sent back home as a gift to the people of our community. No one was really surprised that Miss Ester had taken time to make arrangements for her books. We all knew Miss Ester loved her books better than anything. She had been college educated and was well thought of in literary circles, even as far south as Port Gibson, but we sure never thought she would give her books to us.

There was a lot of talk goin’ around with people trying to guess how many books there would be. Some wondered if they were American books or foreign ones. But talk mostly centered around what in the world we were going to do with those books when they arrived.

The English cousin said she would see to the shippin’ of Miss Ester’s literary treasures. They’d travel first by boat, next by train, and then somebody from our end would have to meet the train at Philadelphia and haul the books home. There was nothin’ to do but wait … and talk … and wonder … and plan as best we could what to do with the first things we had ever owned collectively as a community. It was not something we were accustomed to. We each owned our own land, houses, livestock, and vehicles. We worshipped together at the church house, but the Good Lord owned that. The kids all went to school together in a one-room building over on Duke Miller’s place, but he owned that. We didn’t quite know what to do with something that was supposed to belong to all of us. It was quite a dilemma, and one that wouldn’t be settled without a little dust flying.

* * *

June Ellen flopped herself across the bed, moanin’ and buryin’ her face in the pillow. “I’m gonna be flat-chested all my life, I just know it! I’ll look like a stupid ole boy and nobody will ever want me!” She rolled over on her back, breathed a heavin’ sigh, and dramatically stroked her forehead. I cast a disgusted look in her direction and tried to ignore her mediocre melodramatics as I sat cross-legged on the floor dealing out a hand of solitaire. I didn’t know what had happened to June Ellen, but she had become progressively nuttier ever since she got something called “the monthly visit.” I heard Mama talkin’ to her about it, and I could tell it was some kind of big deal, but I didn’t exactly understand what it was all about. All I knew was that June Ellen had become a basket case of emotions since this “visit” thing started, and I was terrible worried in the back of my mind that it just might happen to me someday. June Ellen was only a year and a half older than I was, and it just might be that I was headed for troubled waters. So, I determined right then and there that I would have no part of this visitin’ business. I just wasn’t cut out for it.

Plop! June Ellen’s pillow smacked me across the back of my head. “Can’t you ever say anything ‘encouraging’ to a person?” she whined at me through clenched teeth. My first notion was to deck her good, but I knew that would buy me a ticket to the woodshed, so I threw the pillow back at her.

“You don’t understand!” she wailed.

“You’re right,” I said, giving up on my game and making my way out the door. “I don’t understand why you want boops in the first place. They make your shirts hang crooked and keep you from being able to slide into home plate.”

* * *

Mama set the plate of hot biscuits on the table and called us to supper. We all joined hands as Daddy said grace. As soon as the “amen” was done, I grabbed the pulley-bone off the chicken platter and snarled my nose at June Ellen. Mama frowned at me and shook her head, so I turned my attention to my plate. Daddy said he had heard down at Hudson’s Store that Miss Ester’s books were officially on their way. Word had it that they would arrive in about two weeks. Mama said we needed to have some kind o’ community meetin’ to decide what to do about the books.

Daddy chuckled a little. “Ellie, people ain’t got time for community meetings and all that stuff right now. Folks are working their crops, trying to scratch a little ahead this year. This book business has just come at a bad time. Shoot, we might as well leave ’em on the train at Philadelphia and let somebody else worry with ’em.”

There was silence. I cut my eyes sideways to look up at Mama. I wondered what she was thinkin’.

* * *

The moon was a big, round, glowin’ ball. It looked as if I could just reach out and touch it. And, oh, how I wanted to. I had these strange stirrin’s inside me, a restlessness of sorts that I didn’t understand. It was like I had this sudden need to reach outside myself, outside my world to somethin’ new, somethin’ different that I had never laid eyes on before.

A horrible thought shot through my mind. Maybe my restless feelin’s meant I was fixin’ to get “the visit” and become as loony as June Ellen. I felt Mama’s hand brush through my hair. I turned my face away from the window, looked up at her, and smiled. She sat down on the bed beside me and looked up at the moon. I looked at her face circled in the glowin’ light. I wondered if she had ever had strange, restless stirrin’s that made her want to dash out into the unknown. I wanted to ask her, but, instead, I heard myself sayin’, “Mama, does God make mistakes?”

A smile curled her lips, and she said, “What makes you ask a question like that?”

“Well, I think I should have been a boy,” I said.

Mama chuckled softly and the bed wiggled. “And may I ask, Miss Constance, what has led you to this earthshakin’ conclusion?”

I puckered my mouth in disapproval. She knew I didn’t like being called Constance. Connie was what I insisted on. But I decided to let it go this time. “I don’t know, Mama,” I said. “I’m just not much of a girl.”

“Compared to whom?” Mama asked.

“Well, I’m nothin’ like June Ellen,” I said, with just the right amount of prideful disgust in my voice. “All she thinks about is talkin’ to boys and growin’ her boops, and I just think it’s all stupid. If bein’ a girl means I have to get light in the head and cry every time somethin’ goes wrong, then I just don’t want to be one. God should have made me a boy!”

I looked back up at the moon. Mama reached up with her hand and gently turned my face toward her. “Connie,” she said, “you were never meant to be like June Ellen, or anybody else for that matter. You’ve got your own ways, your own road to walk. You’ll find it when the time is right.”

“I’ll probably wind up being a lonely old maid like Miss Ester,” I said.

“There are worse things in life than being an old maid,” Mama said. “Besides, Miss Ester was far from lonely.”

“Oh, right,” I said rolling my eyes. “The books.”

Mama ignored my sarcasm. Then she said, “Did I ever tell you that Miss Ester was the first woman in these parts to wear long-legged pants? I can still see her sashayin’ down Main Street, turnin’ every head. Town folks thought it was shameful. Miss Ester thought it was funny. And all us girls couldn’t wait to get us a pair!” Mama laughed. “And when city folks would come visitin’ for Miss Ester’s summer socials, she would serve them this deep burgundy-colored wine in her Mama’s crystal glasses. I know because us girls would help serve sometimes. And, oh my, how fine those ladies would look in their fancy dresses with gloves and hats to match. The gentlemen, of course, were just as decked out in their suits and starched shirts. They’d sit on the veranda or out under the big mimosa trees sippin’ that wine, eatin’ little cakes and biscuits, and tellin’ about books, writers, and places I’d never even heard of. Once, when I was carryin’ a big silver tray back to the kitchen, one of those crystal glasses still had a little of that wine in the bottom of it, and I just couldn’t resist. I turned it up and drank it down quick as a wink. Then, I felt so guilty over what I’d done, I prayed for forgiveness for two solid weeks!”

Mama and I both laughed out loud. June Ellen moaned and pulled the covers over her head. Mama looked up at the moon again. “Oh, I went to sleep many a night when I was your age dreamin’ about those fine ladies at Miss Ester’s summer gatherin’s. Dreamin’ that someday I might be like them. Wearin’ fancy clothes, sippin’ burgundy-colored wine out of crystal glasses and charmin’ folks with talk about books I’d read and places I’d been …”

Mama’s voice trailed off into a stream of silence. I could hear the crickets chirpin’ outside the window and the bullfrogs callin’ to each other down by the pond. Then, for some reason I didn’t understand, a lump caught in my throat, and my eyes welled up with tears. “I love you, Mama,” I said, throwin’ my arms around her neck.

* * *

The next mornin’ as I was finishin’ up my breakfast, Mrs. Mary Mackenly came knockin’ on the front screen door. Mama was surprised but glad to see her. Mrs. Mary wasn’t much of a social visitor. She was a meek woman, slender and pale with dark eyes and hair. She was pleasant to be around, but somehow her quietness had always made me feel a little bit awkward, like maybe if I said too much, I’d be interruptin’ her listenin’ to God or somethin’.

Mama poured Mrs. Mary a cup of coffee and they both sat down at the kitchen table. As Mrs. Mary sipped her coffee, Mama looked over at me and said, “Connie, why don’t you take that jug of ice water on the counter out to your Daddy. He must be powerful thirsty by now.” I knew Daddy probably was thirsty, but I also knew Mama wanted me out of the kitchen. So, I shoved the last bite of biscuit into my mouth, got the jug of water, and went outside.

Daddy was out in the barn workin’ on the old tractor. Mr. Virgil Mackenly, Mrs. Mary’s husband, was overseein’, telling Daddy exactly what he needed to do. Mr. Virgil was a big man, tall, broad, and round, and for some reason the top buttons on each side of his overalls were always undone. I wondered about that. Did he just not take the time to button them, or would they simply not meet? Anyway, Mr. Virgil’s deep, boomin’ voice echoed through the barn along with Daddy’s clangin’ on the tractor. I stood and watched and listened for a while, then walked back out into the bright mornin’ sun and crossed over to the front yard. Mrs. Mary was comin’ down the front steps as I approached. Her dark eyes looked at me briefly, and she smiled a sincere smile. I went up on the porch and leaned against the post beside Mama. Mr. Virgil and Daddy came out of the barn. Daddy thanked him for his help on the tractor, and Mr. Virgil went on to his truck. He and Mrs. Mary drove away in their old green flatbed, bouncin’ down the road kickin’ up a trail of dust behind them.

* * *

I can’t say exactly what it was that woke me, but it didn’t take me long to zero in on Mama and Daddy’s voices. It was unusual for them to talk so loud after June Ellen and I were asleep, so naturally I pricked up my ears and crept over to the door to see if I could tell what was goin’ on.

“I tell you Ellie, it’s foolish, absolutely foolish,” Daddy said from the livin’ room. “I can’t believe Mary Mack even came up with the idea.”

“Now listen here, John,” Mama said. “Don’t you start insultin’ Mary Mackenly. She’s a fine, God-fearin’ woman who believes she’s doin’ what’s right for our community, for our children. Nobody else has volunteered to do it.”

“Nobody else cares, Ellie,” Daddy raised his voice. “Can’t you see that?”

“I care!” Mama snapped.

“Well, good,” Daddy said sarcastically. “And just what do you intend to do about it?”

“I’m goin’ with her,” Mama said.

Daddy laughed. “Virgil Mackenly would sooner lay down and die than let that truck out of his sight. Shoot, Mary’s probably too small to even see over the steerin’ wheel, let alone shift the thing into gear.”

“She’ll do just fine,” Mama snapped. “I’ll drive the truck myself if need be.”

“Oh, great,” Daddy said, “All I need is for you to tear up Virgil Mackenly’s truck out on some hare-brained mission for Ester Cochran. That woman always was two bricks shy of a full load.”

There was silence for a moment. Then Mama said, “When I told you about this, John, I wasn’t askin’ for your permission or you blessin’. I was merely informin’ you of where I was goin’ to be. Now you don’t have to like it. You don’t have to understand it. But I do expect you to respect the fact that I have made the decision that was mine to make, and I will not discuss it anymore.”

Their bedroom door banged shut. I figured it was Mama who had left the room. Daddy was probably still in his chair in the livin’ room, so I slipped back into bed quiet as a mouse and lay there for a long time thinkin’ and wonderin’.

* * *

The next few days were pretty quiet around our house. June Ellen had been pesterin’ Mama to let her go to Cornersville to visit Uncle Will, Aunt Maude, and their teenage daughter Rebecca. Rebecca and June Ellen were like two peas in a pod. Whenever they were together, there was more gigglin’ and silliness than any reasonable body could stand. Finally, Mama gave in, and, on Sunday afternoon, Daddy drove June Ellen over to stay for a few days. Frankly, I was glad to be rid of her for a while. I was tryin’ hard to figure out what was about to take place, accordin’ to Mama and Daddy’s conversation, and, well, June Ellen could be pretty distractin’ when she set her mind to it.

I heard Daddy’s old truck crank up and pull out of the yard. I sat up in bed. The gray light of dawn told me it was still early. The smell of sausage frying in the kitchen told me I was hungry.

Mama was at the stove dabbin’ a little sausage grease from the pan onto the tops of the biscuits that were ready to go into the oven. “Where’s Daddy goin’ so early?” I asked.

“Over to Duke Miller’s to get some weldin’ done for the tractor,” Mama said.

I sat down at the table and rubbed my eyes sleepily. Mama put the biscuits in the oven, poured a cup of coffee for herself and a glass of milk for me.

“I’m goin’ to need you to help out around here a little today,” Mama said as she sipped her coffee. “Mary Mackenly and I are goin’ to Philadelphia to pick up Miss Ester’s books, and most likely we’ll be late into the night getting’ back, so you can see to settin’ your Daddy’s food on the table when he comes in to eat.”

“But Mama,” I said, “I want to go with you.”

“Now, Connie,” Mama said, “this isn’t a pleasure ride. That old flatbed of Virgil’s rides like a log truck, and it’s a long way to Philadelphia.”

“I don’t care, Mama,” I pleaded. “I want to go.”

Mama looked directly into my eyes as if readin’ my very thoughts. Then, she took a deep breath and said, “Okay, but no complaints.”

“No complaints, Mama,” I promised.

It was almost nine o’clock when Mrs. Mary pulled up in our front yard in the old green truck. Mama met her on the porch.

“I’m sorry I’m so late, Ellie,” Mrs. Mary said with a touch of breathlessness in her voice.

Mama reached out and held Mrs. Mary’s hands. “I was beginnin’ to get a little worried. Everything all right over your way?”

Mrs. Mary nodded. Mama looked out into the yard at Mr. Virgil’s old truck. “How in the world did you ever manage that?” Mama asked with a smile on her face.

“Ellie, I waited and waited for him to go to the field this mornin’,” Mrs. Mary began. “But he just piddled around like he had nothin’ to do all day! I thought he never would leave! Then, about an hour ago, your John came by and asked Virgil to go with him over to Hickory Creek to see about a huntin’ dog somebody’s got up for sale. I figured since I was so late you had sent John over to help get Virgil out of the way.”

Mama’s eyes narrowed in the way they do when she’s doin’ some serious thinkin’. “John told me he was going to get some weldin’ done over at Duke Miller’s,” she said.

“Well, anyway,” Mrs. Mary continued, “he was an answer to prayer. As soon as they drove off, I got Leon to help me get the side rails on, and then I dashed over here. Do you think we can still make it, Ellie?”

“Oh, we’ll make it,” Mama said with an air of confidence about her. “But we’ve got to get a move on. Connie’s gonna ride with us. She can keep us entertained with her complaints about June Ellen,” Mama said with a wink of her eye.

Mothers! I thought to myself.

* * *

As it turned out, Mama and Mrs. Mary didn’t need entertainin’. As we bumped and bounced our way from town to town, they took a stroll down memory lane. I had never thought about Mama and Mrs. Mary being girls together. It was so much fun to hear them tellin’ about the things they used to do. Like skinny-dippin’ in Miller’s pond, sneakin’ apples off old man Jessup’s trees, foot racin’ with the boys, playin’ tricks on the teacher … the tales went on and on. As I rode there between them listenin’ to their laughter, I tried to imagine Mama and Mrs. Mary as girls. To my surprise, it wasn’t difficult at all. Maybe growin’ up to be a woman was goin’ to be a good thing after all.

By the time we got to Philadelphia, it was after six o’clock. The train had come and gone, but sure enough, there, on the loadin’ platform, were Miss Ester’s books … crates and crates of them. Fifty-five crates to be exact. And neatly stamped on the side of each crate were the words

“CONTAINS 100 BOOKS.” Mama and Mrs. Mary looked at each other. I did the arithmetic in my head. Fifty-five-hundred books!

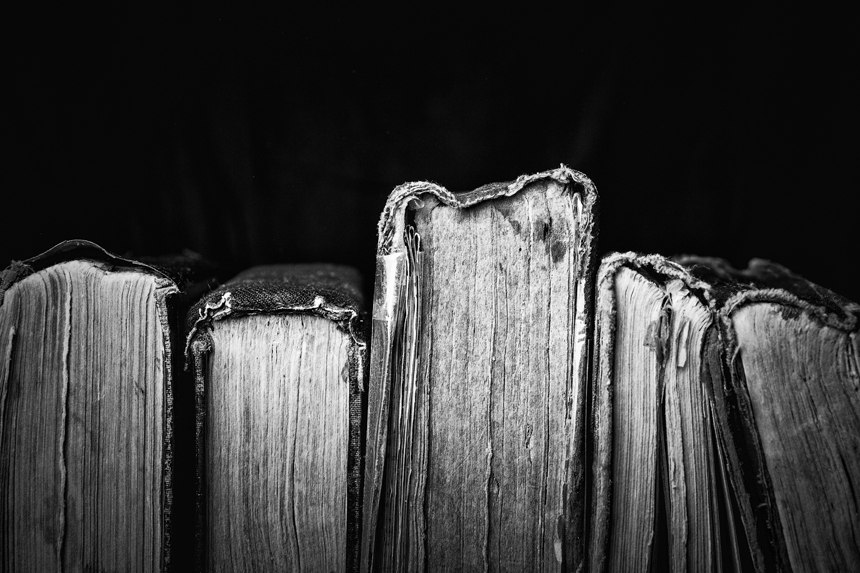

Thank goodness the men at the railway station were kindhearted, for loadin’ those crates onto Mr. Virgil’s truck was no small task. Each crate had to be stacked so it would ride securely, and then a great big tarpaulin cover tied round with strong rope. As the last crate was about to be loaded, Mama asked the gentlemen if they would be willin’ to pry the top off the crate, just so we could check and be sure the books had fared well in their journey. They obliged, and Mama and Mrs. Mary and I peeked inside as the heavy top was pulled away. The smell of old, warm leather raced into my nostrils, and I had the strangest feeling, like I had just been reunited with a long lost friend.

It was after nine o’clock when the work was finally done. Thank goodness Mama and Mrs. Mary had packed ample food for our trip. Before we pulled out of Philadelphia, we polished off the last of Mrs. Mary’s tenderloin and biscuits and Mama’s fried peach pies. The gallon jug of iced tea had long since lost its cool, but it was mighty good just the same.

Mrs. Mary had the engine revved up and was just about to grind it into first gear when she paused and said, “I think we should pray.” And there, in the darkened cab of that old flatbed truck, Mrs. Mary led us in prayer. She thanked the Good Lord for our safe journey and asked Him to carry us back home. She thanked Him for Miss Ester. She thanked Him for the books. She asked Him to bless the books for His sake and to show us how to use them for our good. I had always had the feelin’ that Mrs. Mary walked close to God. After hearin’ her talk to Him, I knew it to be so.

* * *

The ride back home was slow. The dark, unfamiliar roads made the drivin’ hard, and, after a while, Mama got behind the wheel to allow Mrs. Mary to rest. It had started to rain, and the gentle beat of the raindrops on the top of the truck began to lull me to sleep. I laid my head back against the seat and felt the cool, rain-washed night air gently blowing on my face from the open side windows. I felt as if I were driftin’ in a dream.

The next thing I knew, the truck had stopped, and Mama was lettin’ Mrs. Mary take over the drivin’ again. It was getting’ daylight, and I figured we must be pretty close to home. Mama said we had about twenty miles to go. The countryside around us was cool and draped in dew. By the time we turned off the highway and pulled into town, the sun was peekin’ over the treetops.

As we drove up Main Street into the middle of town, an unusual sight caught our eyes. There were a lot of men standin’ out in front of Hudson’s Store. I spotted Daddy right away. And who could miss Mr. Virgil? He certainly stood out in any crowd. “What’s the matter, Mama?” I asked, lookin’ up at her.

“I don’t know,” she said with a frown of concern on her face. She looked over at Mrs. Mary and nodded. Mrs. Mary brought the truck to a stop right in front of the crowd.

Daddy came around to Mama’s side and opened the door. “Tom Hudson is gonna let us keep the books in his store up on the second floor. We’ve moved the other stuff out and everything is ready for the books to go in … if that’s all right with you,” Daddy said to Mama.

Mama was quiet for a moment, then she started to smile. I’ll never forget the look on my Daddy’s face as he reached up, took Mama’s hand, and kissed it. And for one magic moment, I could see my Mama as one of those fancy ladies she used to dream about, being kissed on the hand by a beau she had charmed. Then, as Daddy helped Mama down from the truck, I heard her say, “Now, tell me about that huntin’ dog over at Hickory Creek.” Daddy threw back his head and laughed out loud. They walked arm in arm around the front of the truck and up on the sidewalk where the men had already started carryin’ the crates inside. I saw Mr. Virgil and Mrs. Mary nod at each other, and I had a feelin’ that was all the talkin’ they would ever do on the subject, and, somehow, that just seemed right.

* * *

In the months that followed, things began to change in my world. Mrs. Mary and Mama opened up the Ester Cochran Memorial Library on the second floor of Hudson’s Store. At first, there didn’t appear to be much interest in the library, but, as time went on, customers from the store downstairs began to come up and browse through the books, mostly out of curiosity, I guess. Well, they must have liked what they found, because, before long, people were comin’ to the library and checkin’ out books regularly.

As for me, I fell in love … with reading. I read by the fire on cold winter nights. I read under the shade tree on hot summer days. I read in the car when we traveled. I read late into the night under the covers with a flashlight. Mama vowed I had turned into a regular bookworm, but she said it with a smile on her face.

As for being a girl, well, I decided God had gotten it right after all. Mama and Mrs. Mary were girls, and there was certainly nothing loony or nutty about them. In fact, they were my heroes, along with Miss Ester, of course. Three women full of strength, intelligence, wisdom, and a whole lot of powerful gumption. With examples like that to follow, I had nothing to worry about, except June Ellen, of course, but that’s another story.

To this day, I can close my eyes and still feel the cool of the rain-washed night air on my face as I rode in that old green truck. I can taste Mrs. Mary’s tenderloin and biscuits and Mama’s fried peach pies. I can smell the unmistakable aroma of old books as we opened that first crate. I can hear Mrs. Mary’s prayer of thanksgiving. I can see the men standin’ outside Hudson’s Store, and recall, with vivid memory, the look on my Daddy’s face as he kissed Mama on the hand.

It was a summer like no other, the year I turned twelve. The cotton was high. Living was good. And some unexpected treasures found their way into our lives and into our hearts … the books.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Thank you so much, Mr. McGowan! I appreciate your kind words! And I’m so very happy you enjoyed the story. Thank you for taking the time to let me know. That really encourages my heart!

Very enjoyable story Ms. Gant, not only about the books, but the very determined women who went beyond the extra mile to bring them home, and all that was involved.

I liked your descriptive slice-of-life style story telling here too, that was both insightful and entertaining.