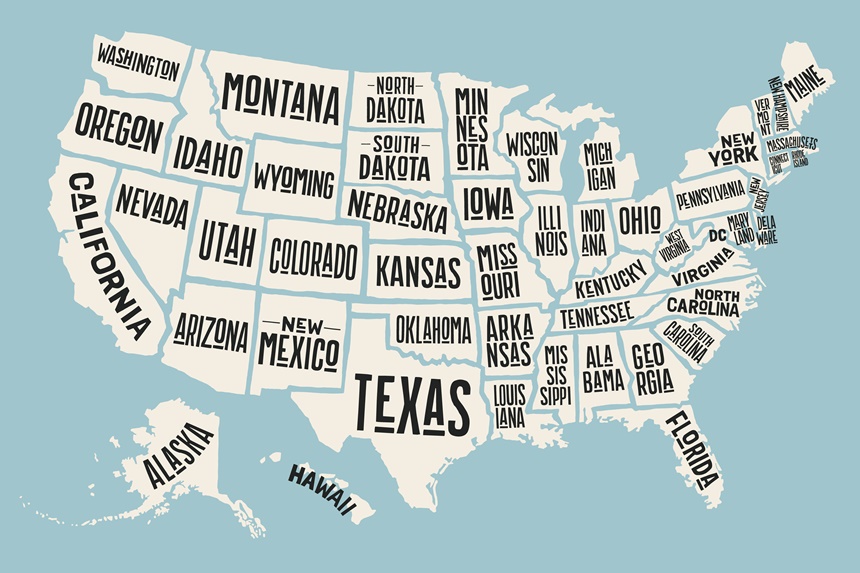

This article features firsts in 25 states: Montana to Wyoming. The firsts in the other 25 states — Alabama to Missouri — can be found here.

In this continuation of “50 States, 50 Firsts,” we explore even more events that happened for the first time in each state. They might be amazing, or unexpected, or just plain weird, but they are all noteworthy parts of the history of the United States of America.

Montana — First Luge Run in America

In snowy northern Europe, sleds and sleighs have for centuries been used not only as a fun pastime but as a regular means of transportation. And, like with every other form of transportation, thrill-seekers found a way to turn it into a sport — or in this case, several sports, including the bobsleigh, the skeleton, and the luge. The activity became popular enough that, in 1957, delegates from 13 countries formed the Fédération Internationale de Luge de Course (FIL); it was admitted into the International Olympic Committee the same year. The first Olympic luge competition was at the ninth Olympic Winter Games in Innsbruck, Austria, in 1964.

The United States didn’t field a luge team that year — the sport hadn’t really caught on here. But after seeing it, some entrepreneurs decided to build their own luge run at the Lolo Hot Springs resort in 1965, the first of its kind in America. Students at the University of Montana organized a Luge Club that would spend weekends there, not only learning how to luge but helping to build and repair the track itself, which by all accounts was pretty roughly made.

That luge run no longer exists today — it proved too difficult and expensive to keep it iced over for much of the year — but a number of those early users found themselves on the first U.S. luge team in time for the 1968 Winter Games.

Fun Fact: Though the skeleton run first became a regular Olympic event in 2002, its first Olympic appearance predated the luge; it appeared in 1928 and 1948 at the Winter Games in St. Moritz, Switzerland.

Nebraska — First Arbor Day

As pioneers and fortune-seekers moved ever westward during the 19th century, some of them arrived in Nebraska to find wide-open plains. A little too wide open, perhaps. They missed their trees, but they also needed trees for shade, as windbreaks, to hold the soil in place, and to provide building material. According to the Arbor Day Foundation, on January 4, 1872, J. Sterling Morton, a newspaper editor in Nebraska City, proposed a tree-planting holiday at a meeting of the State Board of Agriculture. The proposal was accepted, and the first Arbor Day was set for April 10, 1872, with prizes offered to individuals and organizations for planting the most trees. An estimated 1 million trees were planted that day in Nebraska.

The idea caught on in other states, too. By 1882, many schools were hosting special programs for schoolchildren on Arbor Day, teaching about the importance of trees and sending kids home with a sapling of their own to plant. Today, National Arbor Day is marked in all 50 states on the last Friday in April, though some states have their own Arbor Day as well to coincide with the best tree-planting weather for their climate.

Nevada — First Modern Roundabout in the United States

The modern “yield-at-entry” roundabouts that are showing up everywhere around the United States got their start in Great Britain in the mid-1960s. The design, which forces traffic to slow down but simultaneously keeps it moving, lowered the frequency and severity of accidents and, without the need for electric traffic lights, lowered the cost of maintenance and enforcement. It caught on quickly in other nations influenced by the English, such as Australia — but not in the United States.

In the 1980s, other European nations began to test roundabouts too, with France at the lead. Not until the end of the 1900s did American city planners decide to try them out. According to the Federal Highway Administration, the first such modern roundabout was installed in Summerlin, Nevada, in the spring of 1990. Summerlin was a quickly growing planned community west of Las Vegas, and that rapid growth in population also translated to lots of traffic. Roundabouts helped avoid gridlock in the area.

The number of roundabouts in the United States has grown quickly since the turn of the century; today there are more than 10,000 of them across the land, including around 150 in the record-holder for most roundabouts, Carmel, Indiana, a community just north of Indianapolis.

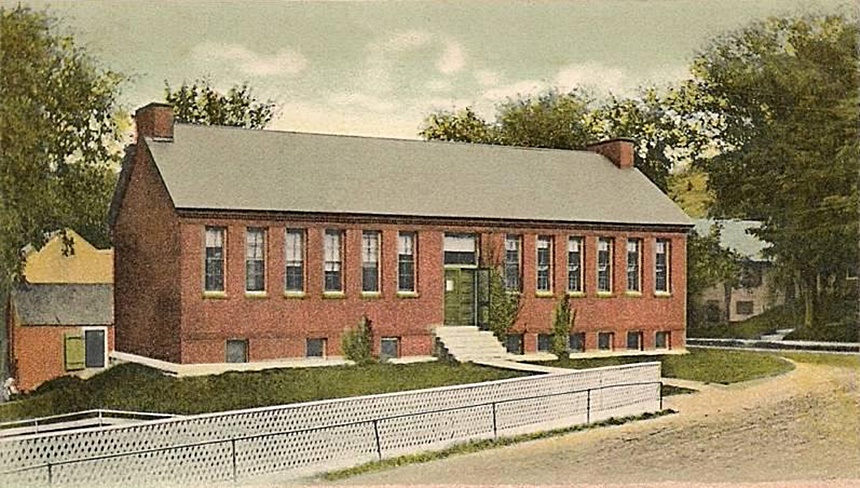

New Hampshire — First Free Tax-Funded Public Library in America

Private and limited-access libraries have existed for ages. Learned societies offered their books for the use of members, companies created them for their employees, and cities and states compiled specialized libraries for use by legislators and attorneys. But in 1833, spurred on by the efforts of the Rev. Abiel Abbot, a Unitarian minister who had created several other libraries for the education and edification of the public, a proposal was made at a town meeting in Peterborough to pool literary resources and create a library owned and funded by the people through taxation. The idea was accepted. Three directors and a committee comprising one representative from each school district were chosen, and the nation’s first free public library was born.

While this was the first free public library, it wasn’t the first free public library building. Starting in 1837, the complete collection was catalogued, and printed copies of the catalogue were given to all families in the Peterborough area. To check out a book, a reader would have to go to the local general store, where the collection was housed. Of course, as the collection grew, more space was needed, so throughout the 19th century, the collection was relocated to the Post Office, then to a local pharmacy, and finally, in 1893, to the purpose-built Peterborough Town Library building.

New Jersey — World’s First Area Code

“Dialing the Nation” (Uploaded to YouTube by AT&T Tech Channel)

In the 1940s, telephone calls were placed through a human-operated switchboard — a caller would pick up the phone and, using both an exchange name and a number, tell the switchboard operator where they wanted to call. The operator would then physically make the electric connections to patch the call through. As you can imagine, as more and more people brought telephony into their homes, an ever greater number of switchboard operators were needed. Plus, if several operators became sick at the same time, you could forget being able to place a call quickly.

Bell Labs saw the problem on the horizon and set about crafting a solution. What they needed was a fully automated calling system, which could only be accomplished with fully numeric phone numbers. One part of their solution was the area code, which would be used to place long distance calls. Most of the “beta testing” for the new system occurred in Englewood, a town near Bell Labs, which means that the State of New Jersey was the first to have an area code: 201.

Why 201 and not, say, 001? The Bell people thought this through, and several rules and guidelines came into play taking into account both human action and the machine that would automatically place the call:

- No area code would use the same digit twice in a row.

- The second digit was either a 0 (indicating that an entire state was covered by that single code) or a 1 (for a state with multiple area codes).

- Areas with high population — and thus receiving more calls — would get lower-numbered area codes because, on the rotary-dial phones for which they were designed, they could be dialed more quickly. New York City, therefore, got area code 212.

To showcase the new system once it was in place, 100 onlookers watched on November 10, 1951, as the mayor of Englewood, M. Leslie Denning, placed a call to the mayor of Alameda, California, Frank Osborn, without the need of a human switchboard operator.

New Mexico — World’s First Atomic Detonation

Uploaded to YouTube by NBC News

This will come as no surprise to the millions of people who saw the recent movie Oppenheimer, but the first atomic detonation in the world occurred at 5:30 a.m. on July 16, 1945, just west of Alamogordo, on what is now the White Sands Missile Range. The plutonium test explosion, codenamed Trinity, was reported by people up to 200 miles away, though the true cause of the blast was kept under wraps until after the bombing of Hiroshima on August 6.

Fun fact: The blast created an immense amount of heat out in the desert. Sand plus heat is a basic recipe for glass, and the Trinity blast was no exception. A usually green, glassy residue — referred to as trinitite or Alamogordo glass — was formed by the melting of the sand around the atomic blast.

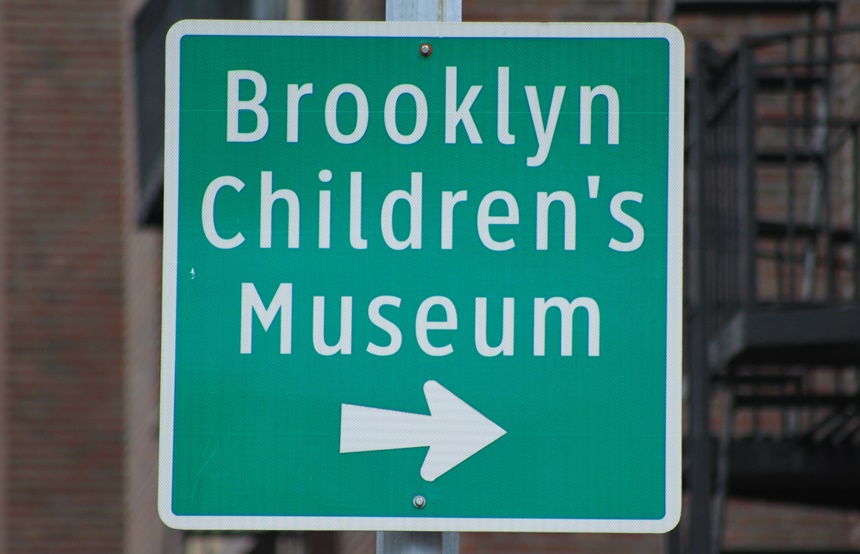

New York — First Children’s Museum in the U.S.

Within a year of Brooklyn becoming a borough of New York City, the Brooklyn Children’s Museum opened in 1899 under the auspices of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences. It was housed in what was known as the Adams House in Bedford Park (now called Brower Park). A first of its kind, the BCM reflected changes in education theory, particularly a greater emphasis on the study of nature. It was open to the public free of charge, and featured displays — with easy-to-read signage written with children in mind — about botany, mineralogy, geography, zoology, and more, and teachers in the area were invited to use the museum’s resources to build their own classroom curricula.

The nation’s oldest children’s museum is still going strong today.

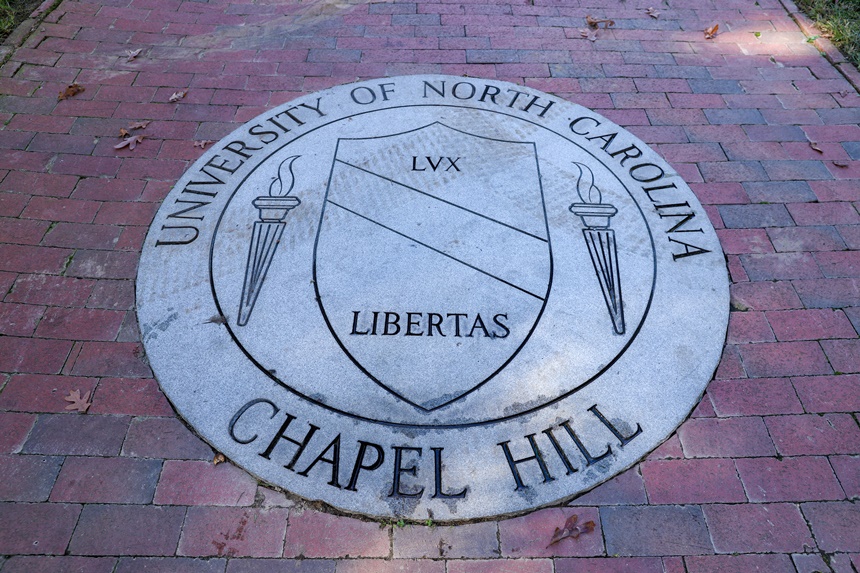

North Carolina — First Graduates from a Public U.S. University

The title of America’s First Public University is difficult to bestow because at least three schools claim it. The College of William and Mary in Virginia was founded by royal charter in 1693, making it the second-oldest university after Harvard — but it didn’t become a public institution until 1906. The University of Georgia became the first state-chartered public university in 1785, but it was a bit slow getting started and didn’t accept its first students until 1801.

Which leaves the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It was chartered by the state in 1789 and began its first semester of classes in 1795, 6 years before UGA. That class received their diplomas in 1798, making UNC the only public university in America to bestow degrees in the 18th century.

North Dakota — First State to Legalize Hemp

“First state” is a bit misleading here. Hemp was perfectly fine and legal for a long time; George Washington even grew hemp at Mount Vernon. But it is a cannabis plant, a relative of marijuana, though it has such little THC that it’s practically impossible to get high on. Nonetheless, as federal drug regulation was starting to take hold in the 1930s, the Marihuana Tax Act placed a heavy tax on the sale of all cannabis products. The broadness of the act was largely political: Paper could be made inexpensively with hemp, which threatened the timber investments of some of the richest men in the nation, including newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst.

Later, the Controlled Substances Act of 1970 made all cannabis products illegal in the United States.

But hemp still held the possibility of being a useful and productive cash crop. So in 1999, two years after the North Dakota legislature passed a law to study industrial hemp production, H.R. 1428 — a resolution to authorize the production of industrial hemp — was proposed, passed, and signed into law, the first state to do so.

Other states followed, but the issue was taken up at the federal level, too. The 2018 Farm Bill cleared the air around hemp nationwide: Though growing it is still restricted and heavily regulated, hemp is no longer lumped in with marijuana in federal drug restrictions.

Ohio — First Professional Tax-Funded Fire Department in America

Through much of the early expansion of the United States, fire departments — relying on buckets and hand pumped water — were volunteer citizens’ brigades or else private affairs. And in those early years, they weren’t necessarily driven by goodwill and the safety of the citizenry. Private, company-owned brigades were employed to protect corporate assets — not only from fire but from competitors’ prying eyes and sticky fingers. And local volunteer departments were sometimes little more than bands of unemployed brutes looking for some easy money. When arriving at a fire, they expected the homeowner to pay for their services before a drop of water was spilled, and if competing fire brigades arrived at the same conflagration, there was liable to be a brawl between them before any firefighting got done.

In some cities, because putting out fires was how people made a living, arson became a big problem. Of course, not all fire departments suffered from this lack of ethics.

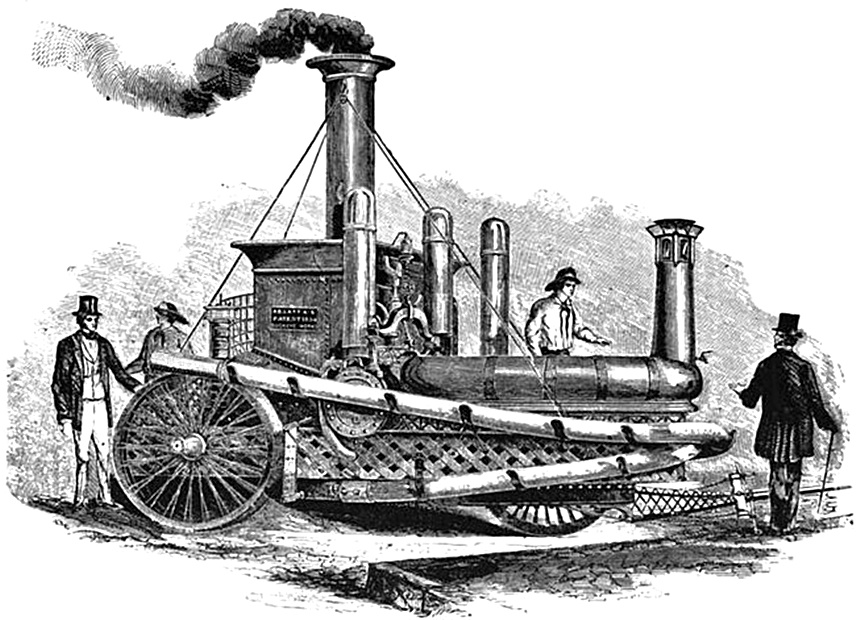

In 1852, Miles Greenwood’s business in Cincinnati was largely destroyed in a fire. Instead of simply mourning his loss, he and two other residents set to work to design and build a better way to fight fires. Their steam-powered fire engine wasn’t the first, but it was one of the most practical and efficient. After demonstrating the machine, the City Council found the funds to establish a full-time fire department, with Greenwood as its first chief, on April 1, 1853.

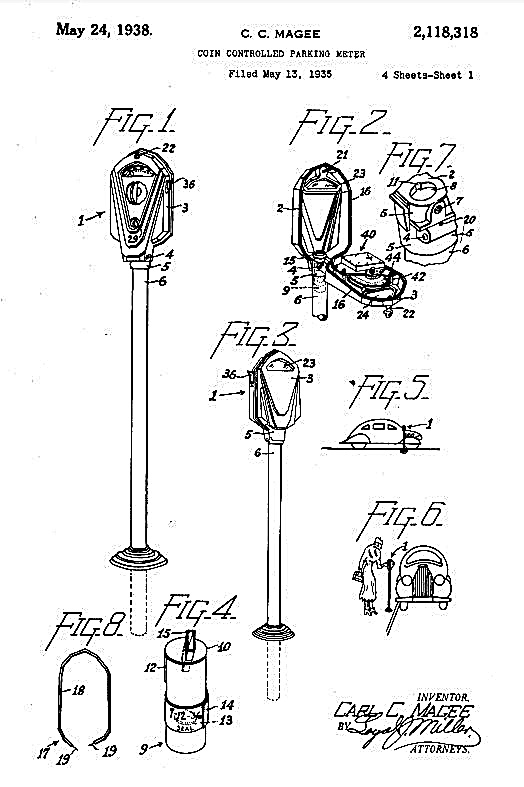

Oklahoma — World’s First Parking Meter

Not all firsts are wonderful things, and they aren’t all what they seem at first. Take the case of the first parking meter: It wasn’t an attempt, as some complained at the time and many claim now, to nickel-and-dime the mobile citizenry and swell the city’s change purse. It was an attempt to fix a real problem.

Some cities simply weren’t ready for the meteoric rise in the popularity of automobiles. Oklahoma City was one such place. The problem with having so many people driving new cars into town was that they all needed someplace to park. With few spaces available, people would park their cars, oh, just anywhere, thus increasing congestion along OKC’s streets.

Enter Carl C. Magee, who had previously established the Oklahoma News but is more widely known today for his mechanical invention, a thing he called the Park-O-Meter. The city authorities let him follow a hypothesis and set up several of them in a small area of the city. Starting on July 16, 1935, these Park-O-Meters sold drivers an hour of streetside parking for 5 cents. The result not only limited the number of vehicles parked on the street, but forced people to either give up their spot to another driver within an hour or pony up another nickel.

And of course, it raised a bit of money — given enough time, parking meters paid for themselves.

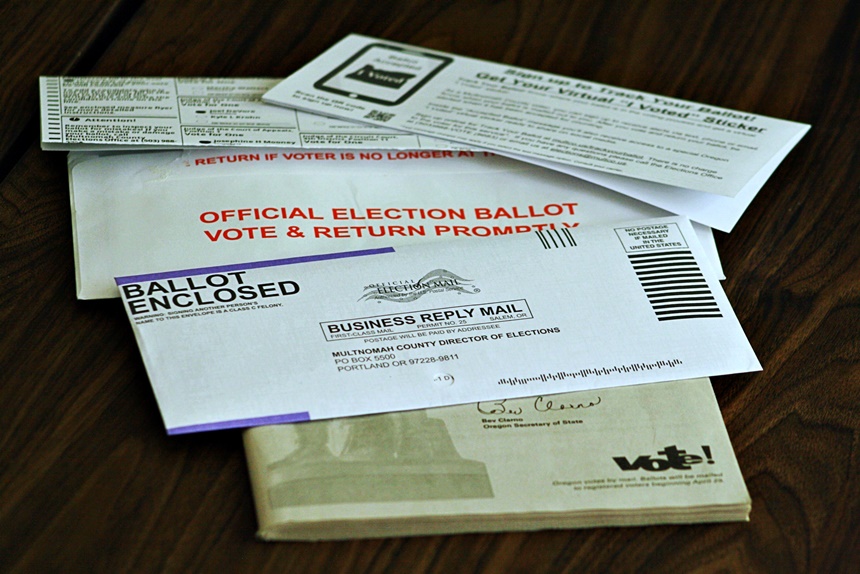

Oregon — First State to Move to 100 Percent Voting by Mail

Oregon didn’t invent voting by mail, but over the last 40 years, they’ve been pioneers in its use. According to the Multnomah County Elections Division, the Oregon legislature approved its first test of voting by mail in 1981, which became permanent in 1987. Vote-by-mail was used largely for local and special elections. But in 1996, Oregon became the first state to conduct a general election totally by mail, to fill the spot in the U.S. Senate left after Sen. Bob Packwood’s resignation. Over several legislative fits and starts, vote-by-mail was expanded in the state. During the primary elections of 1998, Oregon became the first state to have more ballots cast by mail than at polling places.

If you’re waiting for the part where the COVID pandemic pushed vote-by-mail over the edge, you’re going to be disappointed, or maybe pleasantly surprised: Oregon’s general election in November 1998 included a ballot measure to approve moving completely to vote-by-mail. It passed with 69.39 percent of the vote. Which meant that in 2000, a presidential election year, Oregon became the first state to run a regular election entirely through the mail.

Has it been worth it? The numbers show that vote by mail lowers the cost of running an election and raises voter turnout, and voter turnout in Oregon is routinely higher than the national average.

Pennsylvania — Zoological Firsts

The Philadelphia Zoo, which opened on July 1, 1874, bills itself as “America’s First Zoo,” but there are several other zoos still in existence that contest that claim. The places today called the Central Park Zoo (New York City), the Lincoln Park Zoo (Chicago), and the Roger Williams Park Zoo (Providence) started displaying animals in, respectively, 1864, 1868, and 1872. But these were more menageries than zoos.

Regardless, the Philadelphia Zoological Society was chartered in March of 1859 — making it the first zoological society in the U.S. — and the only reason the Philadelphia Zoo wasn’t completed and ready for visitors sooner was because of the Civil War.

Since its opening in 1874, the Philadelphia Zoo has been home to a number of firsts. The first successful birth in captivity in the United States of both an orangutan and a chimpanzee occurred there. It was the first zoo with an on-site animal care center, and the first zoo to develop specially formulated foods for the animals. It’s also home to the country’s first children’s zoo — which, to be clear, is a zoo designed for child patrons, not one where you can gawk at kids in cages.

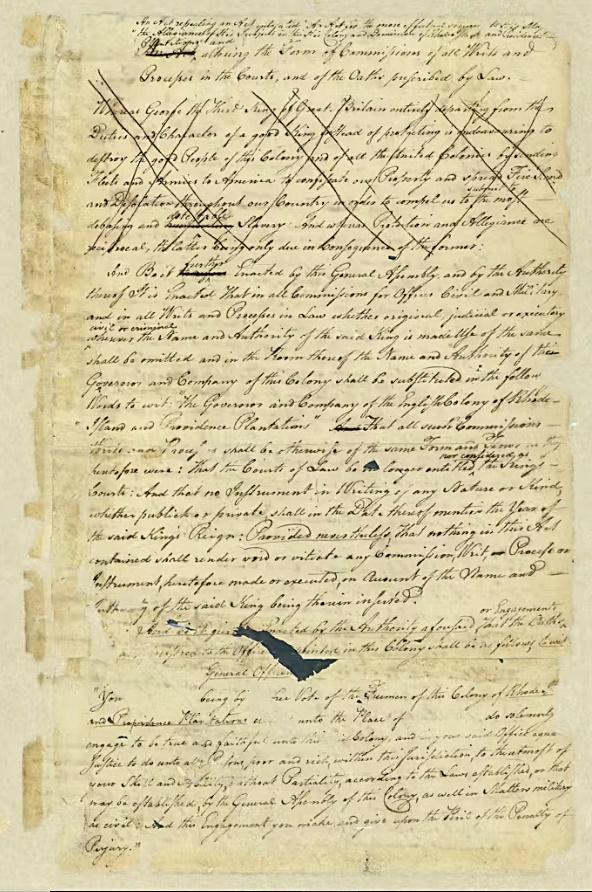

Rhode Island — First State to Renounce King George III

Most of the nation celebrates July 4, 1776, as Independence Day; while the people of Rhode Island do celebrate this federal holiday, they have their own Independence Day two months earlier. But the significance of the date is misunderstood.

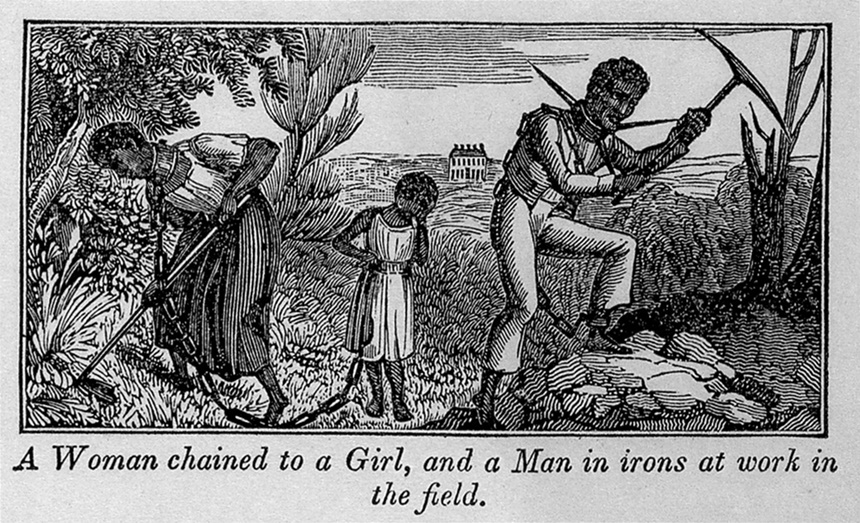

Rhode Island had a lucrative economic triangle that brought molasses from the West Indies to Rhode Island, where it was turned into rum and then traded for slaves in West Africa, which were then traded in the West Indies for more molasses. The Sugar Act of 1764 was just one more attempt from England to squeeze money out of the colonies, and it cut into Rhode Island profits. Anger and resentment in the colony grew, and on May 4, 1776 — exactly two months before that other Independence Day — the Rhode Island government passed an act renouncing allegiance to King George III and removing his name from future legal documents and oaths.

Though May 4 is marked as Rhode Island Independence Day today, that celebration didn’t come about until the early 20th century. The Act of 1776 didn’t declare Rhode Island independent from England — in fact, it repeatedly referred to the location as a colony. It only renounced the current king. Rhode Island was actually the last of the original 13 colonies to approve the Declaration of Independence.

South Carolina — First Opera Performance in North America

When you hear “opera in America,” South Carolina is probably not the first state you think of. Nonetheless, on February 18, 1735, a troupe from England put on a performance of Flora on a makeshift stage in Charleston. The likelihood that you’ve even heard of the opera Flora is pretty low, and if you do know that name, you’re probably thinking of the opera by Joseph Haydn; this isn’t that one.

The Flora that was the first known operatic performance in North America is an English-language opera with words written by John Hippisley (another name you’ve probably never heard) and music written by … well, that’s where some opera enthusiasts might contest the claim that this was a true opera. Flora was a ballad opera, a type of performance that includes some spoken dialogue and that applies new words to popular tunes. Sounds a lot like a stage musical, no?

Nonetheless, Flora returned to Charleston for the 2010 Spoleto Festival, newly reconstituted by composer Bruce Neely.

South Dakota — First (and So Far Only) Corn Palace

The citizens of the small town of Mitchell first came together on Main Street in 1892 to construct a building “conceived as a gathering place where city residents and their rural neighbors could enjoy a fall festival with extraordinary stage entertainment — a celebration to climax a crop-growing season and harvest,” according to CornPalace.com. It was an immediate success, and the festival returned annually.

Now in its third iteration, that now much larger building is host to musical acts, high school and college sporting events, local markets and celebrations, and the annual Corn Palace Festival at the end of August.

What makes this a “corn palace”? Each year, a new theme is chosen, and huge murals are designed for the outside of the building (currently by students in the Digital Media and Design courses at Dakota Wesleyan University). Those murals are then painstakingly produced using kernels of corn in various natural colors. The 2023 theme was the circus, and organizers and designers are now working on the new murals based on the theme of famous South Dakotans.

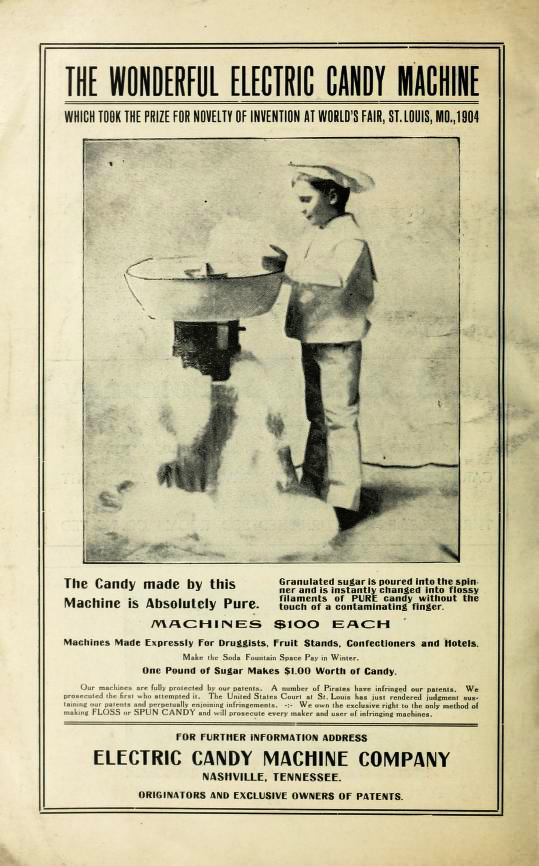

Tennessee — World’s First Ball of Cotton Candy

In 1897, Nashvillian William Morrison got together with confectioner John Wharton and developed an electric candy machine that spun sugar crystals through a metal bowl covered in tiny holes, creating a cotton-like substance made from pure, tasty sugar. They were awarded a patent for it in 1899 and introduced the treat at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904 as “Fairy Floss.”

If you can remember the first time that cotton candy ever touched your tongue, try to imagine being the owner of the first tongue to ever melt the flossy treat. The best part — or the worst, depending on your outlook — is that William Morrison was a dentist, whose side-hustle surely drummed up some extra business for his career.

Texas — World’s First German Chocolate Cake

A recipe for a cake made of chocolate sponges separated by and topped with a pecan-coconut frosting appeared in the daily newspaper The Dallas Morning News as the “Recipe of the Day” in June 1957. The prime ingredient in that recipe was called Baker’s German’s Chocolate, but neither Baker nor German mean what you think they ought to mean.

In 1852, a man named Samuel German — who was not himself from Germany — formulated a new kind of sweet chocolate made for baking, and it was named after him: German’s Chocolate. Samuel German developed his chocolate as an employee of Walter Baker & Company, which sold their goods under the name Baker’s. Thus Baker’s German’s Chocolate.

That recipe that began in Dallas was reprinted in other papers around the country and was a big hit. So big, in fact, that according to one source, sales of Baker’s German’s Chocolate rose 73 percent that year.

Utah — World’s First KFC Franchise

This might seem like a frivolous “first” to highlight, but let me remind you — or maybe alert you to the fact, if you’re under 30 — that the K in KFC stands for Kentucky. How did the first franchise pop up so far from the Bluegrass State?

Peter and Arline Harman bought a restaurant in Salt Lake City in 1941 and set it up as a burger joint called the Do Drop Inn. It was small and struggled for a while, so in 1951 they tore it down and built a larger place they called Harman’s Café. At the same time they expanded their restaurant, they were also looking to enlarge its menu. That same year, Peter had met a restaurateur named Harland Sanders, who had developed a tasty way of preparing fried chicken. In 1952, Sanders visited the Harmans’ restaurant and prepared them a batch of his special chicken himself. All involved were certain that the product would sell well in Salt Lake City, so they worked out an agreement that the Harmans would sell chicken made with the Colonel’s formula, and the Colonel would get a nickel for every piece sold.

Thus, the first Kentucky Fried Chicken franchise restaurant was launched, and it was a huge success. The restaurant is still there today, but it looks like a typical KFC — though there is a bronze statue of Peter Harman and Harlan Sanders outside.

Vermont — First State to Outlaw Slavery

According to the Smithsonian Institution, while the people of Vermont were glad to have been rid of the yoke of British rule, they weren’t originally too keen on joining the United States; they liked their independence. And in an area where Quaker-led abolitionism had flourished, people didn’t believe that freedom should be limited by skin color. On July 2, 1777, the colonial legislature voted to abolish slavery, and elements were even pushing to extend the right to vote to African-American men.

You might notice that it was the colonial legislature. Vermont became our 14th state in 1791, which means that, to put it from a different angle, Vermont was the first free state to be admitted to the Union.

(Rhode Islanders make claims to being the first state to abolish slavery, but they banned only the importation of slaves, allowing the interstate slave trade to continue.)

Virginia — First Successful IVF Baby in the U.S.

The mid-20th century saw new expansion and experimentation in the realm of fertility treatments. Proof of the possibilities of in vitro fertilization (IVF) — in which an egg is fertilized outside a woman’s body and then implanted in her uterus — came in 1978 after Louise Brown, the world’s first “test tube baby,” was born in Royton, England. In the United States, things didn’t go so well. An early and controversial attempt at IVF in New York in 1973 resulted not in a child but a lawsuit. American opinions of IVF as a whole soured, and experiments in it were pushed to the edges of “real” science.

But not everyone felt that way. Howard and Georgeanna Jones, two retired doctors from Johns Hopkins, set up a clinic in Norfolk. They refined the process and were fairly confident they could make it work, but they needed human subjects to test it on.

Thousands of people hoping to get pregnant applied. They chose a woman named Judy Carr. Judy and her husband Roger had been trying to have children since they married, but three ectopic pregnancies had left Judy with no Fallopian tubes; she was therefore unable to have children naturally. Judy was still fairly young — in her late 20s — and because of her condition, there was no chance that she could accidentally get pregnant the old-fashioned way. It made her the perfect candidate.

The fertilized egg was implanted on April 17, 1981 — Judy’s birthday — and the pregnancy developed along largely normal lines. And on December 28 of the same year, at 7:46 a.m., Elizabeth Jordan Carr came into the world, the first IVF baby born in America, a healthy little human. And she’s still one: Elizabeth is now a speaker and advocate for infertility treatments. And she’s a mother herself.

Washington — First State to Ban Texting While Driving

As the parade of technology marches forward, authorities are always playing catch-up to make sure those technologies don’t endanger the citizenry. Enter the smartphone and digital messaging services, aka texting.

At the end of 2006, a 53-year-old man driving his minivan in the express lane of Washington’s Interstate 5 was poking away at his BlackBerry and didn’t notice that the traffic in front of him had stopped. He plowed into the back of a vehicle with enough force that the resulting pile-up included four cars and a bus carrying 28 people, as well as the texting man’s minivan. Thankfully, none of the injuries were serious and no lives were lost. But the accident pushed discussions about texting while driving to the forefront, and the next year Washington made texting while driving illegal, excepting some uses in emergency vehicles. The vast majority of states have since followed suit, and in some places it’s illegal simply to have a cellphone in your hand while you’re behind the wheel.

West Virginia — First State Sales Tax

Taxes are nothing new to Americans. Even before “The United States of America,” taxes were an important sticking point that led to the Revolutionary War. (Remember “No taxation without representation”?) Even after American independence we had taxes, but they were pretty focused on particular items (like whiskey) or specific industries (like imports), and they were usually imposed by the federal government.

But expansion was the name of the game for the U.S., and as state governments and bureaucracies grew, the politicians had to find ways to pay for it all. West Virginia’s solution in 1921 was a broader state sales tax. It was, however, a gross receipts tax, meaning the seller, not the buyer, was taxed. The tax was approved by the West Virginia legislature on May 3, 1921, and went into effect on July 1. In the coming decades, other states followed suit.

Wisconsin — First Kindergarten in North America

In the mid-1800s, Watertown had a large population of German immigrants who spoke German at home. In 1856, Margarethe Schurz — a recent arrival, born Margarethe Meyer in Hamburg in 1832 — opened the United States’ first kindergarten in her own home. Based on the theories of Friedrich Froebel, the educational innovator who founded the world’s first kindergarten in Blankenburg, Germany, in 1837, Schurz’s kindergarten used songs, games, and group activities to focus young children’s energies, develop habits of cooperation, and prepare them for school proper.

Her first class had only five students — four of whom were plucked from her own family tree — but the concept quickly proved both popular and successful.

Wyoming — First State to Grant Women Suffrage

On December 10, 1869, Wyoming’s territorial governor John A. Campbell signed into law a bill granting white women the right to vote within the territory. Though some who supported the bill were motivated by a sense of civility and fairness, many had other reasons to extend suffrage. At the time, men outnumbered women in the Wyoming territory 6 to 1, and the bill found a lot of support from men hoping the national publicity would attract more single, marriageable women.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Portland Oregon has had a roundabout since the 1910s. Its design is very similar to the one in Summerlin, Nevada pictured here, so I don’t know how the Nevada one is more modern than Portland’s.

It’s hard to pick out important ‘firsts’ from the list here, but I’d have to start with Vermont being the first state to outlaw slavery. Wisconsin, with the first kindergarten. Speaking for myself, it was an important transition (school) year between pre-school and the first grade, making the latter an easier adjustment. Washington, being the first to ban texting while driving. The problem would be all the worse without the law, what can I say?

Texas with the world’s first German Chocolate Cake. Mmm, mmm, good. I remember the ‘In A Word’ feature here on this delicious cake several years ago. Nevada, the first modern roundabout in the United States. Then there’s Utah, the world’s first KFC franchise. I had no idea. Colonel Sander’s chicken combined with the already established quality of the Harman’s restaurant, could be nothing less than a successful recipe. I’d love to go back in time to the Do Drop Inn, and thank Mr. Harman in person.