This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

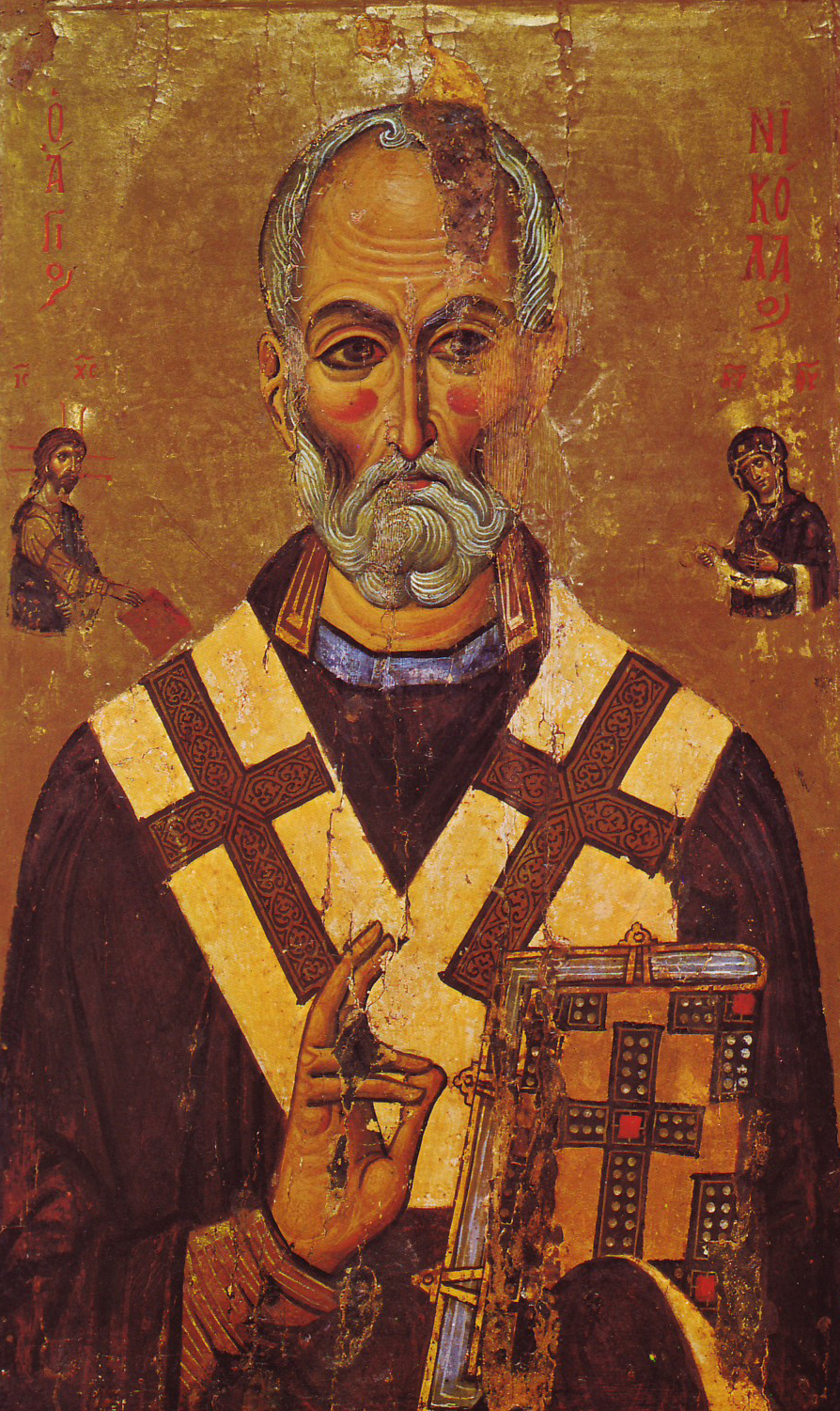

The story of Saint Nicholas, a pious and bearded man known for his charitable giving to the poor, goes back nearly 2,000 years, to 4th century Lycia (modern-day Turkey) where he was the bishop of Myra. Children began receiving gifts in his honor on Nicholas’s Name Day, December 6th, in the Middle Ages. And a folklore character loosely based on Nicholas and known as Father Christmas has been delivering presents and other festive cheer in multiple European countries since at least the 1500s. Like Christmas trees and many other holiday traditions, Santa Claus has a history that long predates the United States.

While Santa Claus did not originate in the U.S., his story and image significantly evolved across 19th century America. And they did so through a series of iconic texts that themselves reflect the growth of the United States over these 100 years. So, for a special holiday Considering History column, here are six texts through which we can trace the evolution of both Santa and America:

1. Knickerbocker’s History of New York (1809)

Long before he wrote such iconic early American folk stories as “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” a precocious 26-year-old author named Washington Irving created this satirical, multi-genre, ahead-of-its-time fictional history of his native state. In it, he translated the Dutch term and character of Sinterklaas into English as “Santa Claus,” one of the first times that name was used in print. It’s only fitting that the man who created so many enduring folk characters helped put Santa on the American map as well.

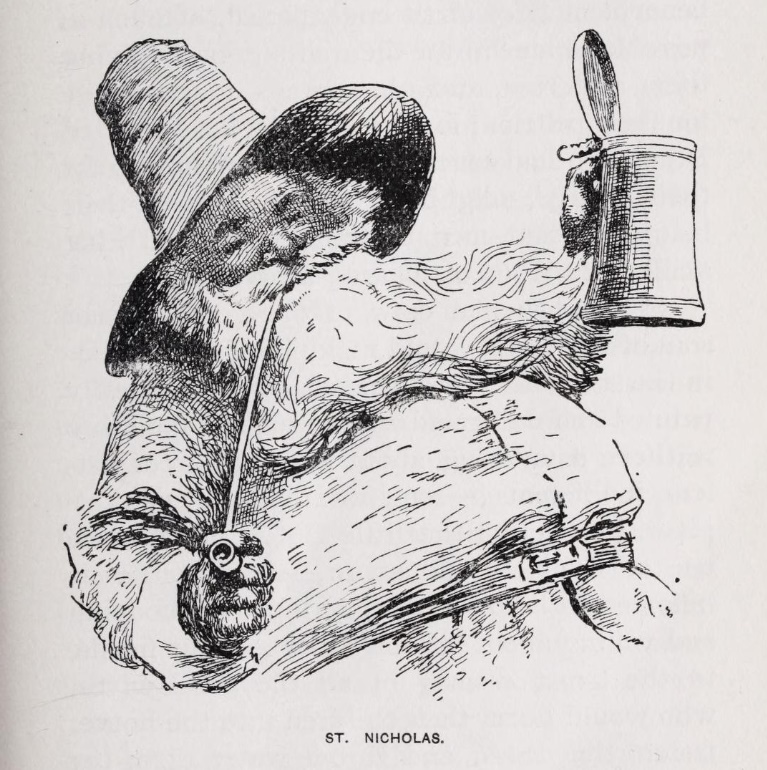

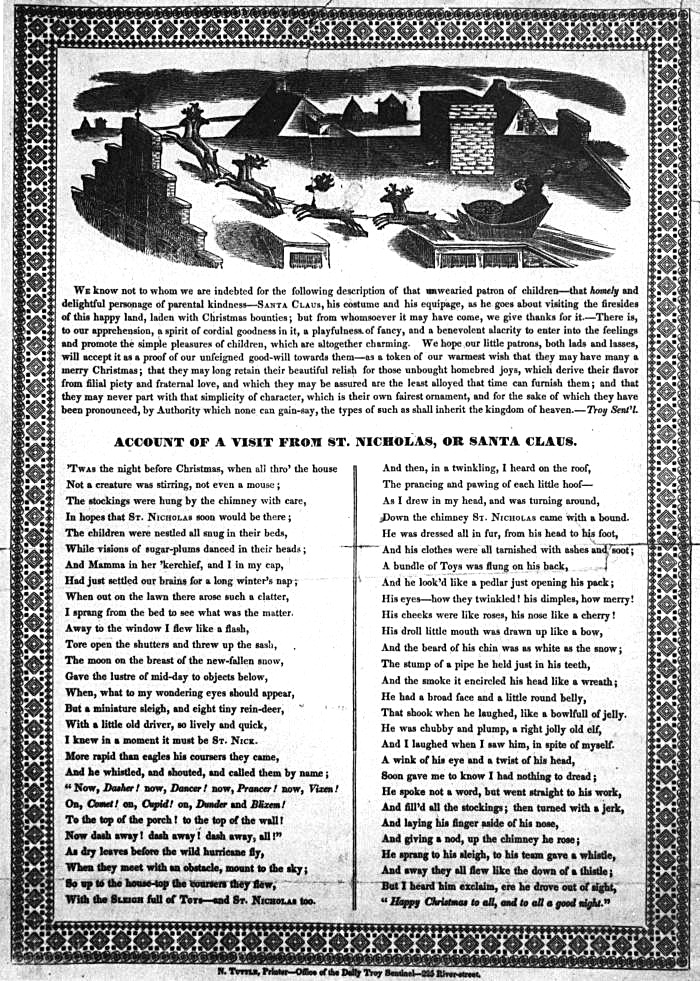

2. A Visit from St. Nicholas (1823)

Like Irving’s other folk characters, his Santa Claus was particularly popular in New York, and so it makes sense that about 15 years later, on December 23rd, 1823, a poem about Santa’s Christmas Eve visit was anonymously published in the Troy, New York Sentinel. Eventually the scholar and poet Clement Clarke Moore took credit for “Visit,” although some literary historians contend it was authored by Henry Livingston Jr.; contests over periodical publications were fierce in Early Republic America, as Edgar Allan Poe could attest. But whoever wrote the poem (which came to be better known by its first line, “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas”) it unquestionably helped establish some of most iconic images of Santa, from his belly and laugh to his eight reindeer.

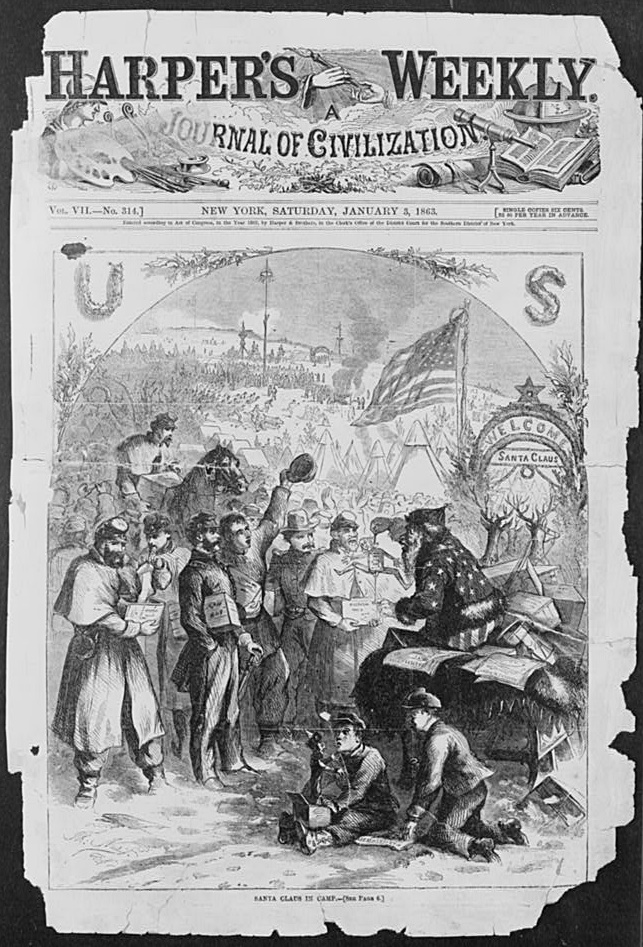

3. Harper’s Weekly Illustration (1863)

If those iconic images of Santa came to exist more fully in visual than textual form, that transformation was due principally to one hugely influential artist: the German American political cartoonist Thomas Nast. Nast first drew Santa Claus for an illustration in Harper’s Weekly’s January 3rd, 1863, issue, depicting him in that Civil War moment draped in an American flag and carrying a puppet named “Jeff” (for Confederate President Jefferson Davis). Over the next few years Nast would broaden his depictions of Santa beyond the Civil War, culminating in texts like his December 1866 Harper’s Weekly collage Santa Claus and His Works. But it’s striking to note how much the first depiction of Nast’s iconic Santa was tied to its Civil War contexts.

4. “Goody Santa Claus on a Sleigh Ride” (1889)

The images of Santa created jointly by Moore’s poem and Nast’s illustrations largely endured throughout the rest of the 19th century, but influential later authors helped add important layers to the story. Wellesley English professor and poet Katharine Lee Bates, best known as the author of the 1893 text that became the iconic anthem “America the Beautiful,” added one such layer with her 1889 poem: Its speaker, Goody Santa Claus, is Santa’s wife, out for a festive sleigh ride and making the case in the process for her own contributions to the holiday. In an era of heated debates over women’s public and political roles, it’s far from coincidental that this professor at a women’s university made such a literary case for Mrs. Claus.

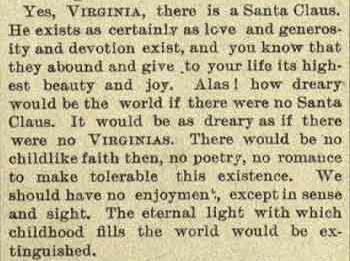

5. “Is There a Santa Claus?” (1897)

Santa isn’t just created by stories and images, of course — he’s also and perhaps especially defined by children’s perspectives. One such child was eight-year-old Virginia O’Hanlon, who in September 1897 sent a letter to the New York Sun noting that her friends had been denying Santa’s existence and imploring, “Please tell me the truth: Is there a Santa Claus?” The newspaper’s affirmative response, authored (anonymously, initially) by veteran journalist Francis Pharcellus Church, appeared in the September 21st, 1897, edition and became one of the most famous editorials in American history. The exchange reflects some of the era’s most prominent trends, from populist tabloid journalism to Progressive reformers’ emphasis on children’s voices and rights. But it’s also simpler than that: “Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus” is one of the greatest single lines in American writing.

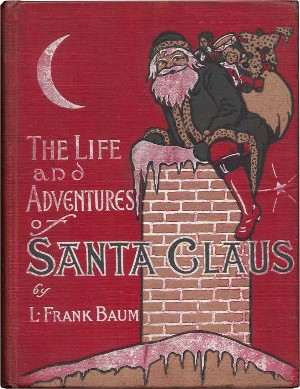

6. The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus (1902)

A great deal of 20th century popular culture was devoted to expanding the Santa story for each generation of children, whether in literary texts like J.R.R. Tolkien’s Letters from Father Christmas (1920-1943), songs like Gene Autry’s “Here Comes Santa Claus” (1947), or films like Miracle on 34th Street (1947). Without question the earliest such 20th century text was L. Frank Baum’s Life and Adventures of Santa Claus, a children’s book that, like all of Baum’s fantastic works, built on existing collective myths, made them new (and a bit strange), and became part of his Oz universe (his Santa reappears in 1909’s The Road to Oz). Baum helped ensure that the 19th century Santa would only grow in popularity as the 20th century got underway — and, like all these authors and artists, helped cement the Claus images that remain so fully with us in the 21st.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Valuble information about saint nick.

For another, historically accurate yet inspiring and entertaining, look at St. Nicholas of Myra, read Mea Nico, by yours truly. It sold out locally and online before Christmas, and the e-book also had brisk sales; but it is a Christian story for ALL time, not merely at Christmas. Enjoy!

Fascinating indeed. There hasn’t been much need at all to ‘tweak’ Santa Claus since the late 19th century.

This is a great bit of history. Worth sharing.

Santa is also the most powerful mutant in Marvel’s X men.