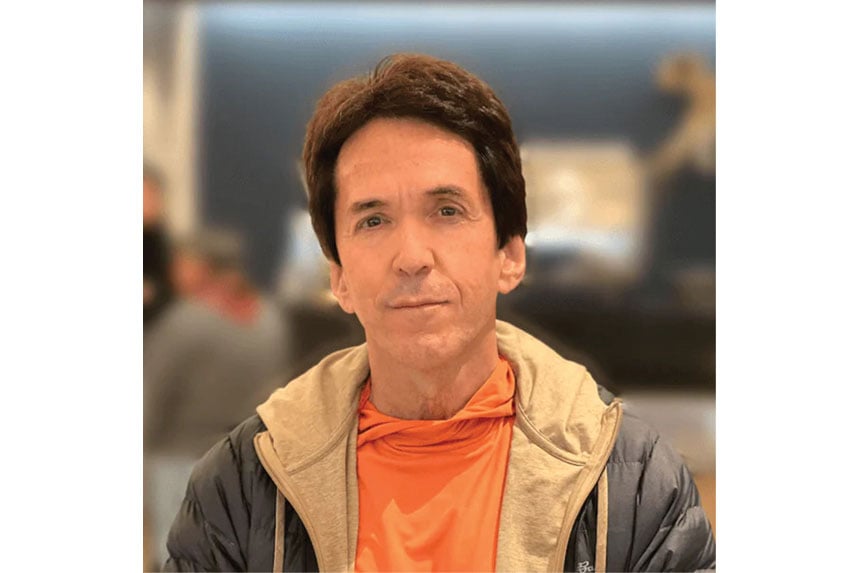

Mitch Albom has touched the lives of millions around the world with his bestsellers, beginning almost three decades ago with the ever-popular Tuesdays with Morrie. Themes of loss, redemption, and the search for life’s meaning in compelling novels like The Five People You Meet in Heaven and Stranger in a Lifeboat are lofty, but Albom takes them to a personal level that has left a lasting emotional impact on readers.

Now Albom is tackling the holocaust in The Little Liar, a wrenching tale of a young boy who has a reputation for honesty who is manipulated into helping Nazis convince Jewish people to board trains to death camps and spends the rest of his life seeking forgiveness. “The connection to our world is obvious,” Albom says. “I think truth has become a very relative term in these turbulent times, and it’s a good time to consider the consequences.”

Writing remains Albom’s passion, but he also devotes himself to a lesson he learned from Morrie. “Giving back is important,” he says of his Detroit charities to aid the down and out and unhoused and of the orphanage he founded in Haiti. “And there’s also listening,” he says. “People want me to hear their stories too.”

Jeanne Wolf: The price of truth and lying are at the heart of your latest book. Do you think we always have to be completely honest?

Mitch Albom: Little fibs are necessary to questions like, “Does this dress make me look fat?” But I think that we all know deep down the difference between a harmless lie and one that does damage. I wanted the book to make people ask themselves, “What’s the worst lie I ever told? What were the ramifications of that lie? Did I lose trust with someone? And what would you do to be forgiven?”

In the end, you know, a lie, if confessed, must be forgiven. I’d rather keep mine private. I’ve learned my own lessons — to be as honest as possible with everybody. I’ve always felt that my books should have some kind of lesson, something that you think about after you’re finished. I’ve tried to get to the core of some kind of truth in every one of the 10 books I’ve written since Tuesdays with Morrie.

There has to be laughter in this world too. Sometimes the best laughs of my life have come when things have just fallen apart. Morrie had a tremendous sense of humor. And so did our adopted daughter, Chika, who I wrote about in the memoir Finding Chika. She had a brain tumor and only lived until she was seven. She made us laugh even when she was dying. I’ve seen the saddest things, and I’ve seen how laughter combats some of the horror. I try to try to find that in myself and put it in my books.

JW: You have sold millions and millions of books. How has fame changed you?

MA: I became well known — famous may be a little too big a word for me — from stories which provided comfort for people who were grieving. So people started to come to me with their grief. Look, very few people have the time or take the time to hear other people’s tales. They’re telling their own stories. Suddenly, I was forced to slow down and talk with thousands — it’s got to be tens of thousands — of people over the years about their sadness. It makes you sensitive to how much suffering people walk around with in their hearts every day. You might pass them in the airport, and they look perfectly normal. Then they see me and grab my arm and start to cry or say, “Can I just give you a hug?” It’s changed my life dramatically from being a sportswriter, where all anybody ever wanted to talk to me about was who’s going to win.

People who criticize my work often criticize it because it’s too hopeful. One critic dismissed me with the sentence, “He’s just the king of hope.” I occasionally remember that and think, “That’s a pretty good throne to be sitting on.”

We’re not destined to be one thing in life. I remember meeting Maya Angelou. I asked her, “Does anyone ever tell you that you should just stick to one thing?” She replied, “Of course, and it’s the cruelest thing because it’s like telling a bird not to fly.” Why couldn’t I write sports and then Tuesdays with Morrie and keep an orphanage in Haiti going. You don’t have to just be one thing. That’s how I’ve tried to live my own life.

JW: Do you have to struggle to find a story strong enough to live up to expectations of you? Is there a new book in the works?

MA: I used to have a notebook by my bedside. When I got ideas in the middle of the night, I would scribble them down … until I realized that I couldn’t read my own writing. So now I send myself emails. Every couple of months, I print out the best. I have more book ideas than I have years left on this earth.

I’m already at work on my next novel, which comes out in 2025. It’s about a person who magically gets to do everything twice in his life. He makes mistakes and then can fix them. Everybody thinks that’s a dream scenario, but there are consequences. The real world is full of unhappy endings and unsatisfied people.

I don’t write my novels to re-create the real world. I try to write them to inspire people who were forced to live in the actual world to maybe step out of it for a few days or hours and imagine the things that could be if we appealed to the angels of our better nature.

This article is featured in the March/April 2024 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now