Franklin Roosevelt could see it right in front of him. His chance. It was a late-June afternoon in San Francisco, the opening day of the Democratic Party’s 1920 convention. Only a few paces away from him, a couple of overfed party functionaries were guarding the standard of New York State. It was nothing special to look at, a wooden sign dangling above the convention floor. But to Franklin it would have been irresistible: Here is greatness. Come and get it.

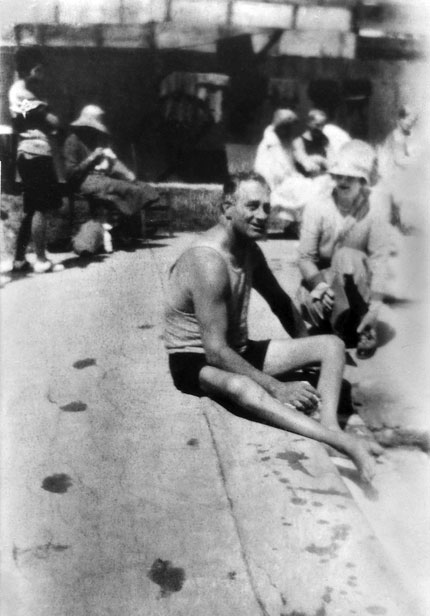

Franklin was 38 years old but looked younger. Handsome, well connected, and eager, he’d spent the better part of the last decade holding high offices — a term in New York’s State Senate followed by seven years in Washington as Woodrow Wilson’s assistant secretary of the Navy. He’d devoted much of his adult life to dreaming of an even higher office — the presidency — and studying the things that savvy politicians did to win it. A convention, he knew, was a kind of game, often a physical one. Playing it well, and looking good while playing, an ambitious young man could prove he had the stuff of a future president — quick wits, a hint of eros, oceans of charm.

Franklin fancied himself that sort of man, and New York’s hanging wooden sign offered a means of proving it. Whenever the convention-floor game got heated, states’ standards became prized possessions, a signal that that state was lining up behind a cause, a platform, or a candidate. Holding the standard of New York, the most populous state in the country, was a chance to show off power. Stealing New York’s standard in a moment of tense drama was a chance to captivate the room. That was what he intended to do: grab the standard and hold everyone’s attention. To get hold of it, he would use his long, lean frame and his quick, elegant stride, the same things that distinguished him on the golf course and tennis court, places where he spent much of his time. And he was also prepared to use his fists.

The trouble had started a few minutes earlier, with the unveiling of the president’s portrait. Woodrow Wilson, the current inhabitant of the Oval Office, had been badly debilitated by a stroke the previous autumn and had not made the trip to San Francisco for the gathering. In his place, the convention’s organizer had hung a giant likeness of the president, the only Democrat to win two consecutive terms in the White House since the Civil War. Shortly after the convention opened, they had pulled back a seven-story American flag to reveal the portrait. State after state had thrown its standard in the air and joined a bandwagon parade in Wilson’s honor.

But New York had not joined the celebration. The state’s delegation was controlled by Tammany Hall, the eternally powerful, endlessly corrupt New York City Democratic machine. Tammany’s boss, Charles Murphy, loathed Wilson and the party’s preening, moralistic “Wilsonian wing.” When the Wilsonian parade had started, Murphy’s delegation made sure to stay put.

Franklin had watched Murphy’s intransigence from the middle of the New York delegation with a striking expression of outrage on his face. Just how real was this outrage was subject to interpretation. There were limits on Franklin’s devotion to any politician not named Franklin Roosevelt, and during Franklin’s seven years serving in the Wilson administration, the president had thwarted his ambitions for greatness as often as he’d helped them along.

But Franklin, a privileged son of New York’s Hudson Valley, was no Tammany loyalist. Indeed, as a young state legislator in Albany, he’d made a name for himself as a noisy opponent of the Hall. A flashy convention-floor display of defiance against Tammany’s authority could serve him well with Democrats from outside New York State. From his place in the middle of the New York delegation, he had loudly demanded that the state join the pro-Wilson parade. And when cries yielded no response, he had set his sights on the state’s standard.

The sign was guarded by a pair of Tammany regulars. If Franklin wanted it, it would mean a fight, one that would almost certainly catch the room’s attention. A fight was a chance to become a surprise star of the convention. And then, perhaps, something more.

For two decades, Franklin had been looking for chances like this. In his college years, he had idolized his distant cousin Teddy Roosevelt, then the sitting president of the United States. He had spent many hours studying Teddy’s path: provocative young politician, then wartime hero, then political phenomenon, then president of the United States. All of it appeared effortless, as if it had been destined from on high.

Perhaps it had been, and perhaps destiny had a plan for Franklin too. Perhaps it was just a matter of finding the right moment to grab hold of the nation’s attention and not let go.

Franklin had been looking for his opportunity ever since.

For Teddy, it had come on a summer’s day in 1898 during the Spanish-American War, when he led his Rough Riders to battlefield triumph. Teddy had been 39 that day, only a year older than Franklin was now.

Of course, this breezy convention hall, pleasantly lit by electric chandeliers, was not exactly San Juan Hill. In fact, if Franklin was to speak plainly of the events of his life so far, something he was not usually inclined to do, he would admit that it had supplied fewer instances of true heroism than had the career of his famed relation. At age 28, when Franklin arrived at the New York capital in Albany as a newly elected state senator, he’d quickly captured headlines, raising hell about Tammany and the urgent need for progressive reform. But there had been less fanfare when he’d left the State Senate a mere two years later; there was not a single piece of significant progressive legislation connected to his name.

Nor was there a dash for the heights with the bullets whistling by: Franklin had spent World War I safely ensconced behind his Navy Department desk. He was a well-liked figure in Washington, where his service as assistant secretary of the Navy was widely judged able and effective. But when Washingtonians looked back on his tenure, they were more likely to remember his elegant, engaging presence at dinner dances than any brilliant policy or project he’d carried out.

It had been nearly eight years since he’d last won an election, to the New York State Senate in 1912. Many of the state’s political establishment thought him an overrated dilettante. Reviewing his career, it seems he was more than happy to play the part of hero, so long as no actual courage was required.

Nevertheless, he had a number of things going for him — a pleasing manner and knack for making other people feel good. “Roosevelt” was still the most celebrated political name of the day, even if the public principally associated it with Teddy and the Republicans.

And he had his looks. Journalists who profiled him — already there had been many of those — invariably lingered on his appearance. His angular, expressive face was the sort, a writer for the Washington Post observed, that “could set the matinee girls’ hearts throbbing.” Slim and well-proportioned, he stood six feet two inches tall. His was, said New York World, “the figure of an idealized college football player, almost the poster type.” Watching him jump over a stream near his home in Hudson Valley, one friend thought he looked “like some amazing stag.”

Franklin was realistic enough to understand that, when combined, his assets as a politician were hardly enough to earn him a seat at the top of the Democratic ticket in 1920. But the bottom of the ticket was another matter altogether.

All he had to do was find a way to show the people gathered in that convention hall how much he had to offer. He ran forward, toward the New York sign.

Reaching up over the heads of the Tammany Hall guards, he pulled the standard down and pivoted toward the center of the convention floor. Before he got more than a few paces, however, other New York delegates were scrambling toward him, grabbing for the sign. When Franklin managed to evade them, they grabbed at him too.

Soon he was in an outright struggle as more delegates tripped into the chaos, pushing and ruffling him, knocking the hat off his head. Fists flew, his and theirs. A policeman dove into the fracas, lunging at Franklin, who screamed theatrically in protest and then violently shoved the man away.

By this point, he’d caught the attention of the reporters in the press gallery. They lapped up the spectacle — an actual fight! In the dispatches they would later file, they disagreed over the details: who had thrown the first punch, whether Franklin had lost his eyeglasses, his tie, his coat. But there was no debate over the victor in the scuffle. They’d all seen Franklin easily dispatch each man who’d come at him until, after a few minutes, he escaped unmolested, the standard in his hand.

Clutching it to his chest, he bolted toward the ongoing Wilson parade, offering New York and himself. Everyone in the room was looking at him as he leapt over a row of chairs. He smiled in triumph as he turned to look up toward the galleries. By the next day, his name would be on the front pages of newspapers nationwide. By the end of the convention, his performance would help win him a spot on the ticket as the party’s vice-presidential nominee.

Few would remember anything Franklin had to say at that convention. Few would even remember much he said that entire election year. But in that moment, as in so many moments in Franklin’s life leading up to it, what mattered was not words but appearances. And few would forget how splendid Franklin looked as he made his fantastic run.

On a summer night almost exactly 16 years later, Franklin Delano Roosevelt sat in the back seat of a limousine as it moved across a stadium field. It was just after sundown on June 27, 1936, the last day of another Democratic convention, this one in Philadelphia. As his car drove slowly toward a speaker’s platform in the center of the field, Franklin could see a massive crowd of 100,000 people who had come out to see the convention’s crowning event.

Through the window of the limousine were signs of how much politics had changed in the intervening years. A portrait of Woodrow Wilson hung along one end of the stadium but only as one in a row of dead Democratic presidents, unknown and unmissed by the younger people in the crowd. The party had long ago stopped dividing itself into Wilsonian or anti-Wilsonian wings. It was a Roosevelt party now.

Franklin was 54 years old but looked older. The patrician angles of his face were absorbed by billowing flesh; his skin was sectioned by deep lines. Beneath his navy serge suit, his chest had filled out and his arms were thick from years of conditioning. Inside his trousers, the legs he’d used to leap like an “amazing stag” were now shrunken and contained by heavy braces of thick steel.

Franklin’s performance at the 1920 convention had indeed earned him a place as his party’s vice-presidential candidate, alongside the presidential candidate, Ohio governor James M. Cox. But their ticket was defeated in a landslide in the general election that November. Nine months later, in August of 1921, he had been stricken with a grave sickness while vacationing with his family on Campobello, an island off the coast of Maine. For days, he’d lain in fevered agony, unable to move below the neck. Feeling his control over his muscles and bodily functions slip away, he wondered if he would live.

The infection had passed and in time he’d regained the use of his upper body. His life, however, was transformed by the illness, eventually diagnosed as infantile paralysis, known to later generations as polio.

The disease had robbed him of the use of his legs, aged him ten years overnight, and appeared to put his old dream of winning the presidency out of reach. Political insiders mostly wrote him off for dead.

But from the earliest days of his recovery, Franklin refused to surrender his ambition of someday returning to politics and running for president. Convinced that doing so would first require regaining the ability to walk, he had spent seven long years away from the hunt for elected office — in politics, several lifetimes — devoting his days to taxing and often fruitless rehabilitative schemes. All the while, with the assistance of his wife, Eleanor, and his devoted adviser, Louis Howe, he had nurtured a strategy for an eventual return to elected office — a multiyear plan that was detailed, complex, and secret.

His moment had come in 1928 when he surprised the New York political scene with a last-minute candidacy for the state’s governorship, then shocked the nation with a decisive win. He had leveraged a strong performance in that office to wage a successful campaign to be his party’s 1932 presidential nominee. In November of that year, he defeated the reviled incumbent Republican president, Herbert Hoover, in a landslide.

Franklin had assumed the presidency in March of 1933, the darkest hour of the Great Depression. One in four adults was out of work, the nation’s financial system was on the brink of collapse, and the republic itself seemed in mortal danger. But beginning with the extraordinary legislative activities of his first hundred days, he had reinvented the role of the federal government and remade much of American life with the sweeping programs of the New Deal.

By the summer of 1936, he was already thought to be the most significant American president since Abraham Lincoln. Most important, though millions of Americans remained hungry and out of work, Franklin’s energy and magnetic charisma in office had transformed the country’s spirits. The previous day, the Democrats gathered in Philadelphia had rapturously nominated him for four more years in the White House. At ten o’clock that night, he would accept the nomination in front of the crowd of 100,000, in a speech broadcast over the radio nationwide.

As Franklin’s car moved slowly across the field, an excited voice on the loudspeaker announced his arrival. The faces in the crowd strained for a glimpse of him, but most saw nothing. That was all right by Franklin. On that long-ago day in San Francisco in 1920, he’d had to scheme about ways to get people to look at him. Now his challenge was the opposite: making sure people did not see too much.

Despite his efforts, he had never regained his ability to walk. In private, he moved about most comfortably in a dining chair that had been refashioned as a wheelchair; at times when he’d needed to move somewhere quickly, he had been known to drop to the floor and crawl across a room. He could, with some practice, move around on crutches, placing one crutch in front of him, pivoting his weight at the hips so that his legs swung out in front of him. But without a companion’s arm to steady him, his progress was ungainly and fraught with peril.

When he’d returned to active political life, Franklin’s great fear had been falling in front of an audience. Over the years, he had been carried up countless sets of stairs, had been pushed through the window of a train compartment, had been dangled down onto a stage from a fire escape. Whatever it took to avoid being jostled, losing control, falling to the ground.

The car came to a stop when it reached the back of the platform. Franklin had long since perfected a method for exiting an automobile. Swiveling his torso to the side, he would extend his arms up, waiting for a pair of strong hands to pull and lift him out of the car. Outside the vehicle, he would steady himself, taking the arm of whoever was tasked with supporting him. Tonight, as on many nights, that person was James “Jimmy” Roosevelt, Franklin’s 28-year-old eldest son. At the back of the convention speakers’ platform, he took hold of Jimmy’s arm with one hand; in his other hand he held a cane he used to help steady his weight.

On the platform, a large group of dignitaries and party leaders swarmed toward him. Among them was Edwin Markham, the 84-year-old “dean of American poetry,” who had just finished reciting a poem he’d composed for the occasion: “Franklin D. Roosevelt: Man of Destiny.”

White-bearded, with large, expressive eyes, the aged poet approached Franklin to say hello. As he drew near, however, Markham was jostled by the crowd and lost his footing. Falling forward, he struck Jimmy Roosevelt, who in turn lost his own footing and fell into his father. Absorbing the blow, the steel brace on Franklin’s right leg gave way. Franklin struggled to regain his balance, but his body crumpled. As he fell headfirst toward the floor of the platform, the pages of the speech he was about to deliver scattered in the air.

Seeing the president slip, a Secret Service agent dove forward to catch him. Just before Franklin touched the ground, the agent thrust his shoulder under Franklin’s armpit, arresting his fall and scooping him up. James A. Farley, Franklin’s political adviser who was now serving as chairman of the Democratic Party, quickly led a group of other officials in forming a tight circle around Franklin. They knew without being told what to do in Franklin’s moment of exposed vulnerability: Don’t let people see. Within their shelter, Franklin’s heart raced — he had fallen before but never in so public a setting. He could hear the roar of the hundred thousand, waiting for him, watching for him. Don’t let them see.

Meanwhile, Franklin’s attendants held him in the air and refastened his brace. “Clean me up!” Franklin commanded. He was anxious and agitated. Seeing his pages strewn all about, he barked orders about “those damned sheets.” There wasn’t time to prepare a clean copy of the remarks — the radio broadcast was set to begin in mere moments.

A chaotic scene followed: people dusting him off, chasing after stray pages. “Okay,” he finally announced when all the sheets had been recovered, “let’s go.” But as he and Jimmy resumed their progress, Franklin caught sight of Edwin Markham a few feet away, weeping over all the trouble his stumble had caused. On Jimmy’s arm, Franklin went over to the old man, took him by the hand, and offered a reassuring smile. All would be well.

Soon he was at the speaker’s stand, smiling broadly as the crowd cheered him. Then, with stagey exaggeration, he looked at his watch to remind his audience of the impending broadcast and signaled for them to hush. Just after ten o’clock, he began to speak. The speech he gave that night in Philadelphia would be one of his most celebrated. In it, he sought to provide context for the work his administration had done over the previous three-and-a-half years to save the country from ruin. Yet Franklin knew that for many listening to his words, his presidency was something greater than just restoring the country’s economic health. In his first term, he told them, he’d sought to renew the nation’s spiritual purpose, to replace the pursuit of narrow self-interest with a more nourishing generosity and concern for humankind. “In the place of the palace of privilege, we seek to build a temple out of faith and hope and charity.”

As he concluded his remarks that night, he spoke of destiny: “There is a mysterious cycle in human events. This generation of Americans has a rendezvous with destiny.”

Destiny was indeed a mysterious thing; Franklin Roosevelt had learned that long ago. As a young man, cosseted in his own palace of privilege, he had believed himself destined for glory. He had thought that if he followed a straightforward path from success to success, greatness would surely come. Then one awful day, illness had surprised him, mocked his certainty, and tossed his expectations of triumph aside.

But that stroke of fate that had turned his legs lifeless had also made him the man who could inspire and lead his country that night. Polio had remade his life, created a more gifted, intuitive, compassionate politician, made him a better man. It had taught him the one thing that his country needed most: how to find hope in the darkness and how to share it with the world.

Jonathan Darman is a journalist and historian who writes about American politics and the presidency. He is the author of Landslide: LBJ and Ronald Reagan at the Dawn of a New America.

From the book Becoming FDR: The Personal Crisis That Made a President by Jonathan Darman, Published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Jonathan Darman

This article is featured in the March/April 2024 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

NOTE: A correction to my previous post (see below). Apparently FDR was NOT the 1st president to take the oath of office in The White House. It seems that Rutherford B. Hayes was. Because March 4, 1877, was a Sunday, Hayes took the oath of office privately on Saturday, March 3, in the Red Room of the White House, the first president to do so in the Executive Mansion. He took the oath publicly on March 5 on the East Portico of the United States Capitol.

FDR has had a number of “firsts” or records in American Presidential history:

Most times (5) nominated on a major national ticket (1920 for VP; and for president 1932, 36, 40 and 44). The only other with 5 is Richard Nixon (VP in 1952 & 56; president in 1960, 68 and 72).

One of several men to be his party’s presidential nominee for a major party at least 3 times. The others include Andrew Jackson (1824, 28 & 32); Grover Cleveland (1884, 88 & 92); William Jennings Bryan (1896, 1900 & 08); Richard Nixon (1960, 68 & 72); and presumably Donald Trump (2016, 20 & 24).

First to take the presidential oath of office 4 times. The only other being Barack Obama: On Jan 20, 2009; then re-administered the next day privately due to 1st oath strayed slightly in wording; In private ceremony Jan 20, 2013 (a Sunday); In public ceremony the next day Jan 21.

First president to be inaugurated on a January 20th date (in 1937, to start his 2nd term, meaning his 1st term wasn’t a full 4 years).

First president to be inaugurated at The White House rather than the usual U.S. Capitol building. This was in 1945. The other two presidents to do likewise were Harry Truman (also 1945) & Gerald Ford (1974).

The first, and so far only, president to have 3 VP: John Garner, Henry Wallace & Harry Truman. Other presidents have had two VP, the most recent being Richard Nixon (Spiro Agnew, Gerald Ford).

First sitting president to fly in a plane, in 1943.

I’m sure there are many other “firsts” for FDR. Can anyone supply others?