Senior managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

In the same way that, before writing systems were developed, a culture’s stories were passed down orally, so too was the Western musical tradition long passed from generation to generation without the benefit of a way to put the music on parchment.

Much of modern musical notation finds its beginnings in the old Church, at a time when monks were expected to perform specific liturgical chants daily. These traditional chants weren’t written down — younger monks learned them from the more experienced monks and would in turn pass them down to the next generation.

But eventually clerics and musicians alike wanted a physical record of these chants. And that’s what early versions of notated music were: An archival record, not a piece of music you would sing from. Those early charts showed the shapes of the music but with little specificity. They didn’t so much indicate what to sing but how to sing it, and so they were only useful if you already knew the melody.

But as man got more creative and music got more complex, new notation systems were needed.

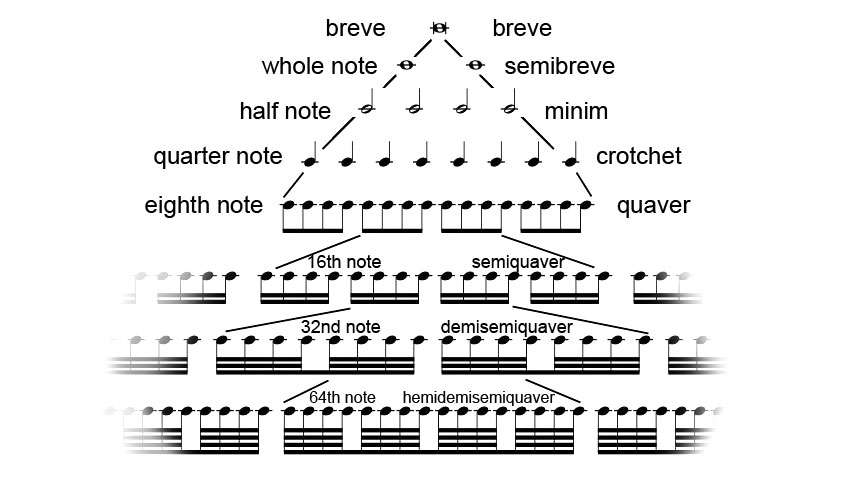

There are many aspects of music that can be notated — pitch, volume, pulse, articulation — but here we focus specifically on note length. American music students today learn about whole notes, half notes, quarter notes, and the like, but each of those notes also has a name that isn’t so mathematical. You don’t hear those names often in America, but many British musicians still refer to notes in these ways.

Breve

Returning to ye olden days: Before about the 12th century, musical notation really only had notes of two lengths — long and short. Just how long and how short was a matter of tradition and the musical sensibilities of whoever was leading the chant. The longa was, you guessed it, the long note. The short note was called a brevis (meaning “short”) in Latin; further down the timeline, this became breve in British and American English.

You can find the breve in modern music, but it’s fairly rare — it’s equal to the length of two whole notes and is the longest individual note length there is. That’s ironic considering it began as the shortest division of a note.

Semibreve, the Whole Note

I wrote about semi- and a few other prefixes that mean “half” two weeks ago, and here we find it being used in music. The semibreve etymologically is “half a breve,” and that’s what it was in early music … sometimes. Early Church music was obsessed with groups of three — indicating the Trinity — and so sometimes three semibreves were used in the space of one breve. As music got more complex, that simply wasn’t enough, and some musicians actually crammed up to 12 notes in the space of a single breve, but they still called each of them a semibreve.

One ultimate goal of notation was to have the ability to write a song in such a way that someone else could learn it without having ever heard it. This two-note system wouldn’t do. And so in Paris in the early 14th-century, we started to see innovation.

It’s worth noting that early breves and semibreves did not look like the modern-day breve and whole note (see the image at the end). Older music used note groupings and color to indicate pitch and relative length, but a new system was developing that indicated length by the shape of the note. And that’s where we got a third note value.

Minim, the Half Note

In the 14th century, we find in the works of Philippe de Vitry the first mention of the semibrevis minima, literally “the shortest semibreve.” This would soon be shortened to just minim in France, which migrated to the musical vocabulary of England and stayed there — the half note is still called a minim by some British musicians, but it wasn’t the shortest note length for long.

The relationship between the minim and semibreve is like that of the semibreve and the breve — that is, one semibreve was usually as long as either two or three minims.

Crotchet, the Quarter Note

Here we get the first note name that doesn’t come from Latin Church music. In England, the minim was divided into two crotchets (quarter notes).

Crotchet — used in music from the mid-15th century — comes from the Old French crochet, a diminutive of croc “hook.” A crotchet, then, is “a little hook,” and the name comes from the fact that the quarter note — even more so then than now — looked like a little shepherd’s crook.

And yes, crotchet is etymologically related to crocheting — needlework similar to knitting but that uses a single needle with a small hook in the end to create warm scarves and hats.

Quaver, the Eighth Note

In the early 1500s, if someone sang with a tremulous tone — either from inexperience, nerves, or an intentional vibrato or trill — their singing might be said to quaver “to vibrate or tremble,” probably from an earlier Low German word.

When you divided a crotchet in half, the resulting note might mimic the speed of that quaver in a singer’s voice. Thus when a note of this speed was written down, it was called a quaver — an eighth note by American standards.

And They Only Get Shorter

When it came time to name even shorter types of notes, someone else (besides me, that is) noticed that there were three similar prefixes that all mean “half,” and they decided to go ahead use all of them. First was the semiquaver, “half a quaver” or a 16th note; then, adding another prefix, the demisemiquaver, “half a semiquaver” or 32nd note; this was followed by the rare-but-not-so-rare-that-it-doesn’t-need-its-own-name hemidemisemiquaver, or 64th note.

You could theoretically continue cycling through the prefixes (in the same order) and halving the note lengths further, but actually using a hemidemisemihemidemisemiquaver — a 512th note — would only earn you the disdain of the musicians who are expected to perform the work.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

Love this week’s feature (all of them of course) as it deals with music, and the the history of what those notes mean and their origins etymologically. I had/have a basic enough knowledge of how to read them, and hit the right notes.

My mom had me taking piano lessons at 10/11 (’68) largely based on the beautiful instrumental hit of the time ‘Love Is Blue’ by Paul Mauriat. We had an upright piano, but I wished it was a harpsichord instead, as that was what the song featured as well as strings, brass and woodwinds (the oboe). I got pretty good at it, and the sheet music did make sense.

I also kind of like the way the notes look. Unfortunately today, I can only play the first 13 notes of Carole King’s ‘I Feel the Earth Move’, and still do in homes or other places I’m at where there’s a piano for fun, showing off to get reactions, and taking a bow afterwards. It’s better than nothing, and definitely better than ‘Chopsticks’! As far as ‘Blue’ goes, the one with the blue water background (on YT) is the perfect visual montage to go with it.