You might see Everest in the morning, our trek leader tells us, gesturing toward the cloudy horizon after our second day of hiking in the Himalayas. It’s been an exhilarating two days hiking up to Namche Bazar, the Sherpa village and historic trading crossroads of the Khumbu region on the Nepali side of Everest.

Our group of 17 people — mostly from the U.S. but with others from Australia, Argentina, and Norway — traverses paths lined with bright magenta rhododendrons and lavender wild irises. Cable foot bridges grace the landscape like elegant silver necklaces. Below us is the Dudh Koshi, the Milky River, the meandering turquoise stream that patiently carved this valley. At every settlement there are prayer wheels, brightly painted with heartfelt sentiments that with every spin are catapulted far and wide.

To mark the 70th anniversary of the first ascent of Mount Everest (and my 60th birthday), my wife Jackie and I are trekking to Everest Base Camp with Jamling Norgay, the son of Tenzing Norgay Sherpa. On May 29, 1953, Tenzing and Edmund Hillary were the first people to reach Everest’s summit, which at 29,035 feet above sea level is the highest point on earth.

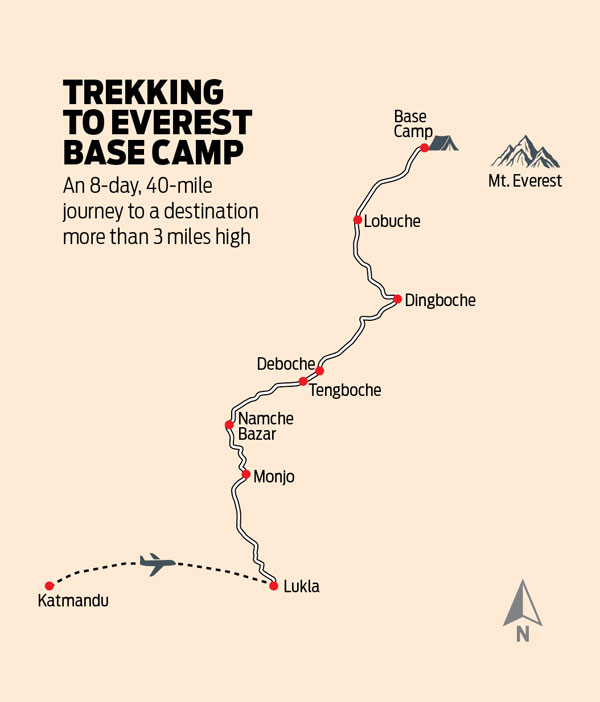

Base Camp is our ultimate destination; we have no intention to climb the high reaches of the mountain. Our trek is about 40 miles, a series of climbs to high ridges followed by steep descents into river valleys, and the diminished oxygen at high altitudes makes the journey challenging for those of us who reside near sea level.

Day 1

Kathmandu to Lukla to Monjo (9,200 feet)

Reading Jan Morris’s Coronation Everest — the exclusive account of the 1953 British expedition that was the first to reach Everest’s summit — I learn that back then Nepal had no roads outside of its capital; the only way to get to Everest Base Camp was to walk 200 miles from Kathmandu. After arduous days of hiking, the climbers crawled into tiny tents, so low they could barely sit up.

Our journey begins quite differently. After three days at the luxurious (by Nepal standards) Hotel Yak & Yeti, where we enjoyed sumptuous buffet breakfasts and sipped gin and tonics at dusk, we fly from Kathmandu to Tenzing Hillary Airport in the vertiginous village of Lukla.

The plane flies lower than nearby mountaintops, zipping between peaks. Then we seem to drop straight down to Lukla’s impossibly short runway, so short that planes can only stop in time thanks to the 12-degree upward slope — the landing is the most frightening of my life.

We shoulder our packs and begin our trek. Six Sherpas hike with us, showing us the way whenever the trail splits and offering to carry our days packs on steep climbs. “If you need to give a bag to a Sherpa, give it to him,” Jamling says. “We want you to get to your destination, with a smile.”

We share the trail with dzos (rhymes with nose), pack animals that are half yak, half cow whose bells form a euphonic soundtrack to the cinematic views of the snowcapped Himalayan peaks. The animals, despite being heavily laden, walk faster than we do, and our instructions are clear: When animals pass, always stay to the uphill side of the trail. Dzos and yaks have a nasty habit of knocking tourists off trails and down into the valleys below. We keep our distance and scramble a couple of feet above the trail whenever we see a caravan coming.

Day 2

Monjo to Namche Bazar (11,300 feet)

A village of about 2,000 people built nearly vertically on terraces, Namche Bazar occupies a semicircular valley. It’s a centuries-old trading post and the hub of the Khumbu region, with stacked buildings that look like life-size versions of Monopoly hotels.

And it’s more sophisticated than nearby villages. After stashing our packs at the convivial and comfortable Namche Hotel — we have our own bathroom with hot showers! — we walk 15 minutes uphill to visit the Tenzing Norgay Sherpa Heritage Center that opened May 29, 2023.

Outside the heritage center, Jamling takes a moment to gaze at a statue, a likeness of his father Tenzing Norgay, who became a hero in Nepal when he reached Everest’s summit on that momentous day in 1953, a dozen years before Jamling was born. The statue, capturing the moment Tenzing triumphantly held his ice axe aloft on Everest’s summit, is strategically placed to enjoy a view of the soaring mountains.

“Many years ago I thought my father should have his legacy in the Everest region, but there was nothing. So I thought why not put a statue of him over here,” Jamling says, sweeping his arm across the Himalayan panorama. “This is one of the best spots in the entire Khumbu to look at the mountains. Everest, Ama Dablam, all of them. You get a 360-degree view of all the mountains here when it’s clear.”

After years of fundraising and hard physical labor, the statue has been unveiled and the museum refreshed and expanded. With stone walls and wooden beams, the airy museum was a “huge undertaking,” Jamling said. “To make anything up here is 10 to 15 times more expensive than in Kathmandu because everything has to be carried up” by people, pack animals, or helicopters. Jamling next plans to add a cafe in a glass outbuilding and a Wall of Fame for Sherpas who have reached the summit of Everest or who acted heroically in the Himalayas. “After that I’m going to retire,” he tells us with a laugh.

This isn’t our first visit to the region. In 2018, my wife and I joined Jamling on a trek through Nepal’s medieval Mustang region. Back then I was excited to be trekking with the son of one of the world’s legendary climbers, who is an accomplished mountaineer in his own right. For this trip to Everest Base Camp, I was looking forward to traveling with Jamling again, not because of what he’s accomplished, but simply for who he is: an engaging storyteller with a wry sense of humor.

Day 3

Namche Bazar layover (11,300 feet)

After the first two days of trekking, we have an acclimatization day in Namche to help us adjust to the altitude. Six of us, all friends from northern California, get up at dawn for a pre-breakfast hike back to the Tenzing Heritage Center, hoping to glimpse Everest. At home I’m not an early riser, but somehow in the Himalayan foothills, I wake naturally at sunrise, fueled by adrenaline and excitement for the coming day. The air is crisp and cold. The weather zips from sunny to overcast, with fluffy, cauliflower-shaped clouds obscuring the mountains.

Suddenly the clouds lift. We see Everest, the mountain that the local people call Chomolungma, a Tibetan name meaning “Goddess Mother of the World.” Its pyramid-like shape and nearly horizontal lines of rock and snow are unmistakable. Soaring above 29,000 feet, the mountain seems impossibly distant — I’m thrilled to see it but making it from Namche to the 17,600-foot high Base Camp feels like a pipe dream. I’m already huffing and puffing at Namche’s elevation of 11,300 feet.

“How am I going to make it in just five days?” I ask my wife.

“One step at a time,” she says with confidence. “One step at a time.”

We hike back to the lodge for breakfast, like all our meals a communal affair with our group and other trekkers. This is one of the great joys of trekking: meeting travelers from around the globe as well as Sherpas, sharing stories, and making friendships.

Mid-morning, we hike to the hamlet of Thesho, where tragedy has struck. A month earlier, shifting blocks of ice in Everest’s Khumbu Icefall claimed the lives of three Sherpas, two of whom are from this village. Jamling tells us two of the men were his cousins and that insurance payments for Sherpas who die on Everest barely cover funeral expenses.

A creek near Thesho is enlivened by more than a dozen lines of prayer flags, brightening the landscape in the Tibetan colors of red, blue, green, yellow, and white. In Thesho, with an introduction from Jamling, I interview one of the widows, Pasang Sherpa, who is wearing a gray sweatshirt and black pants, her graying black hair pulled back into a bun. Sitting atop the two-foot-high stone wall bordering her yard, I ask how she’s feeling, and she doesn’t hide her pain. “Very bad,” she says, clutching her stomach. She and her husband were going to move to Kathmandu with their nearly two-year-old daughter after this climbing season.

I ask her to tell me about her late husband. “He was a good man, a good father,” she says in English, through tears. “When I met him I was a lucky girl. Now there is no one to care for me.” She invites me inside her home and shows me a shrine with about 40 lighted yak-butter lamps glowing golden. As she carries her daughter on her back, Pasang holds up what looks like a high school photo of her late husband. In the photo that is barely bigger than a postage stamp, he appears too young to shave, but it may be the only photo of him that she has.

Back in Namche, we go to a bar that’s screening the IMAX film Everest, which documents Jamling’s 1996 attempt to follow his father’s footsteps to the summit. “For 50 years or more, those who tried to climb to the summit failed or died,” Jamling says in the film. “Then, in 1953, the first two climbers reached the top, Edmund Hillary and my father, Tenzing Norgay. When I was just five years old, I lit butter lamps to honor the mountain gods who protected my father at the top of the world. He said the mountains gave him great strength. I thought he was the bravest man on Earth. Now, 43 years after his great climb on Everest, I’m training for my own summit attempt. I think it’s in my blood.”

As we watch the film in the darkened bar, I wonder if the other trekkers who’ve wandered in for a pint have any idea they’re watching Everest with the man who’s on the screen. In the film, shaken by the deaths of eight of their fellow climbers, Jamling and his team, led by veteran climber Ed Viesturs, consider abandoning their summit attempt. But then Jamling recalls his climb has been blessed by an elderly monk and chooses to continue. He reaches the summit on a gloriously sunny morning.

“I didn’t think getting to the top would change my life, but it has,” Jamling says in the film. “Up there above the clouds, I touched my father’s soul. Ever since I was a boy I’ve looked up to him, but I always felt kind of a hunger inside to live up to his legend. I know he’d laugh to see me on the summit of Mount Everest. He’d say, ‘Jamling, my son, you didn’t have to come such a long, hard way just to visit me.’ As if he knew all along I was worthy of the mountain.”

Day 4

Namche Bazar to Deboche (12,000 feet)

We’re on a wide path above a valley, so high that helicopters fly thousands of feet below us. Everywhere we look, we have up-close views of the mountains: Thamserku, Nuptse, and the twin-peaked Llotse. At a small village, vendors sell earrings, necklaces, and singing bowls to passing trekkers. It’s a steep climb to Tengboche monastery; we break for tea and I lie down. Jamling fears I’m dehydrated, but it’s just a cold or flu bug that’s sapping my energy. A Sherpa named Mingma walks with Jackie and me and kindly offers to carry my pack. At first I resist but then hand it over.

Tengboche is the largest monastery in the region, known for its mountain views and golden Buddha. Guided by a monk, we light butter lamps in memory of a courageous friend who died a few weeks before the trip, the wife of the friend a longtime travel editor who introduced us to Jamling. Words come to me: “May her spirit be liberated and soar freely.” It rains as we leave the monastery. I imagine the drops are tears for our departed friend.

Day 5

Deboche to Dingboche (14,500 feet)

We wake to views of Everest through the windows of our lodge and have breakfast with long-distance runners who are trekking to Base Camp and then will run the Tenzing Hillary Marathon, from Everest Base Camp to Namche Bazar, on May 29, the date of the first successful Everest climb.

Leaving Deboche, we hike past mani walls — composed of chiseled stone slabs inscribed with prayers. After a six-hour day of hiking, we arrive in Dingboche, a small village that boomed with the influx of Everest trekkers. Our home for the next two nights is the spartan Snow Lion lodge. The best thing about it: an adjacent cafe that brews whipped-cream-topped mochas, the perfect antidote for the chilly weather at nearly 15,000 feet.

Day 6

Dingboche layover (14,500 feet)

Our goal on this acclimatization day is to hike at least 1,000 feet up a hill near the lodge, spend some time near or above 16,000 feet, and then come back down for our second night in Dingboche.

After the chilly morning hike, a member of our group, an Italian chef named Riccardo, takes over the kitchen and makes a huge pot of pasta. At high altitude, I’ve been eating mostly dal bhat, an easy-to-digest plate of lentils and rice with spinach. But when I smell Riccardo’s pasta my appetite returns with gusto, and the pasta — which took ages to cook because water boils at 184°F here compared to 212°F at sea level — is as hearty and delicious as it smells.

That afternoon we retreat to Cafe Himalaya, a coffee house and climbing museum of sorts, with boots, ropes, ice axes, and snowshoes from 20th-century expeditions. Seeing the heavy woolen clothes and clunky boots reveals how much gear has evolved. Back in 1953 they had oxygen tanks, but these were impossibly heavy and bulky compared to what’s now used.

At the cafe we sip lattes and watch the 2015 documentary Sherpa that was being made when a horrific ice avalanche in the Khumbu Icefall on April 18, 2014, killed 16 Sherpas who were working to set up camps for Western climbers. Survivors were angry about the meager settlements offered, yet the disregard for Sherpas’ lives continues to this day.

Day 7

Dingboche to Lobuche (16,100 feet)

Above 15,000 feet the dzos give way to caravans of yaks, which are heartier and burlier. These shaggy caravans, announced by the crystalline sound of their bells, and human porters are the primary methods for moving supplies through this roadless region. We stop at a memorial for climbers on Thukla Pass. More than 100 climbers are honored with stones piled into monuments, including Scott Fischer, who died in 1996 during a blizzard while descending from the peak.

Our lodge in Lobuche, the EBC Guest House, is animated by chatter in several languages, as a wood stove’s heat embraces us. A man from India is video-calling his family on speakerphone, telling his two-year-old he loves him and will be home soon. An Italian girl applies lipstick while Jackie and I sip ginger lemon tea. There are showers here with hot water fueled by the propane hauled by yaks all the way from Lukla. A shower costs 800 rupees (about $6) and is money well spent.

Day 8

Lobuche to Everest Base Camp (17,600 feet)

Today is the day we’ll reach Base Camp — if our legs hold up. As we hike toward Everest, the terrain gets rockier and we have to scramble over some waist-high boulders. Extending my leg to reach a rock, I feel a twinge in my knee, and I’m still battling the cold or flu I picked up earlier, but we’re so close, nothing can stop us now.

It’s desolate here above tree line, like walking on the moon. The air is only 11 percent oxygen, about half of what you’d get at sea level. It’s a sky-blue morning; we can see snow blowing off the tops of nearby peaks. Soon clouds come in; snow and ice crystals fall from the sky. Climbing to the top of a ridge, we can see Base Camp below. Greeting us as we reach camp is a sign spray-painted on a flat rock reading, EVEREST BASE CAMP, 5364m.

“We made it,” Jackie and I tell one another, hugging at a place that until this moment had felt mythical. “We made it,” I say again, almost as if I’m trying to convince myself. It still doesn’t seem real. I’ll never get to the top of Everest, so this rocky plateau is my mountaintop. And though we can’t see the mountain from here, I’m elated.

The Sherpas have created a village with an expansive geodesic dining tent large enough for two long tables. We feast on sausages, rice, cauliflower, and hot fried potatoes. We’re on the flank of a desolate mountain, dining like royals. It’s amazing that Jamling and our crew, without pack animals, pulled this off. Exhausted but energized, we hike about 15 minutes to the nearby Khumbu Glacier and explore its luminous curtains of aqua-blue cascading ice and icicles that are taller than us. Then, giddy from our accomplishment, we start hurling snowballs at one another.

Our tent has mattress pads — an electric light with three brightness settings illuminates the interior. We may be camping on the world’s highest mountain, yet we’re living in luxury, a far cry from the rough discomfort endured by the 1953 climbers. Maybe it’s the altitude, but it all feels like a dream. Snug in my sleeping bag, I sense what we’ve accomplished, that far more than the physical feat, we’ve shared a moment of communion with the local people and their place, perhaps a fleeting connection, yet one we’ll long remember.

Day 9

Descent from Everest Base Camp: Snow flurries during the night have covered the camp with fine powder. With a long day ahead, we pack our bags by 5:30 a.m. We have breakfast and are hiking by 6 a.m., the grunts of yaks and shouts of their handlers are audible from hundreds of yards away.

There’s one thing we still want to do. We’ve saved some prayer flags to hang at Base Camp in honor of author Jan Morris, the author of Coronation Everest, who became my good friend after we met at a travel writing seminar in 1992. Years later Morris invited me to Wales and showed me Mt. Snowdon, where the Everest climbers trained. In 1953, it was Morris who brought to the world the news of the successful 1953 summit, on the eve of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

Jackie and I find a ridge and hang the colorful streamers, gratified that we could offer a small tribute to this pioneering writer. As we descend, I spot Subash, a Sherpa in our group, greeting the rising sun with outstretched arms. It’s a perfect portrait of one Nepali’s connection to the mountains and natural world. I quickly take a photo, then we continue onward. Everest is now behind us, and though my knee barks with every step, it’s all (well, mostly) downhill from here.

Michael Shapiro is a freelance journalist whose writing has appeared in National Geographic, Sierra, AFAR, and the San Francisco Chronicle, among other publications. He is the author of the books The Creative Spark and A Sense of Place.

This article is featured in the January/February 2024 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now

Comments

The narration is such that one feels the real impact of the arduous and hazardous trekking to the Everest Base camp by the author , accompanied by his wife. Very absorbing too. One wonders how food was managed during the trek.